2450 words

The New York Times published an article on December the 8th titled What Doctors Should Ignore: Science has revealed how arbitrary racial categories are. Perhaps medicine will abandon them, too. It is an interesting article and while I do not agree with all of it, I do agree with some.

It starts off by talking about sickle cell anemia (SCA) and how was once thought of as a ‘black disease’ because blacks were, it seemed, the only ones who were getting the disease. I recall back in high-school having a Sicilian friend who said he ‘was black’ because Sicilians can get SCA which is ‘a black disease’, and this indicates ‘black genes’. However, when I grew up and actually learned a bit about race I learned that it was much more nuanced than that and that whether or not a population has SCA is not based on race, but is based on the climate/environment of the area which would breed mosquitoes which carry malaria. SCA still, to this day, remains a selective factor in the evolution of humans; malaria selects for the sickle cell trait (Elguero et al, 2015).

This is a good point brought up by the article: the assumption that SCA was a ‘black disease’ had us look over numerous non-blacks who had the sickle cell trait and could get the help they needed, when they were overlooked due to their race with the assumption that they did not have this so-called ‘black disease’. Though it is understandable why it got labeled ‘a black disease’; malaria is more prevalent near to the equator and people whose ancestors evolved there are more likely to carry the trait. In regards to SCA, it should be known that blacks are more likely to get SCA, but just because someone is black does not automatically mean that it is a foregone conclusion that one has the disease.

The article then goes on to state that the push to excise race from medicine may undermine a ‘social justice concept’: that is, the want to rid the medical establishment of so-called ‘unconscious bias’ that doctors have when dealing with minorities. Of course, I will not discount that this doesn’t have some effect—however small—on racial health disparities but I do not believe that the scope of the matter is as large as it is claimed to be. This is now causing medical professionals to integrate ‘unconscious bias training’, in the hopes of ridding doctors of bias—whether conscious or not—in the hopes to ameliorate racial health disparities. Maybe it will work, maybe it will not, but what I do know is that if you know someone’s race, you can use it as a roadmap to what diseases they may or may not have, what they may or may not be susceptible to and so on. Of course, only relying on one’s race as a single data point when you’re assessing someone’s possible health risks makes no sense at all.

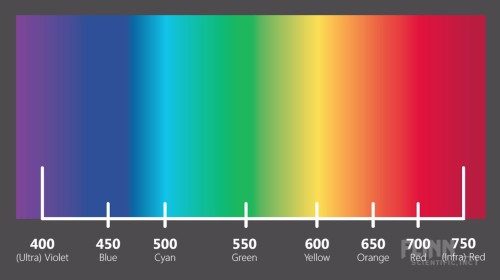

The author then goes on to write that the terms ‘Negroid, Caucasoid, and Mongoloid’ were revealed as ‘arbitrary’ by modern genetic science. I wouldn’t say that; I would say, though, that modern genetic science has shown us the true extent of human variation, while also showing that humans cluster into 5 distinct geographic categories, which we can call ‘race’ (Rosenberg et al, 2002; but see Wills, 2017 for alternative view that the clusters identified by Rosenberg et al, 2002 are not races. I will cover this in the future). The author then, of course, goes on to use the continuum fallacy stating that since “there are few sharp divides where one set of traits ends and another begins“. A basic rebuttal would be, can you point out where red and orange are distinct? How about violet and blue? Blue and Cyan? Yellow and orange? When people commit the continuum fallacy then the only logical conclusion is that if races don’t exist because there are “few sharp divides where one set of traits ends and another begins“, then, logically speaking, colors don’t exist either because there are ‘few [if any] sharp divides‘ where one color ends and another begins.

The author also cites geneticist Sarah Tishkoff who states that the human species is too young to have races as we define them. This is not true, as I have covered numerous times. The author then cites this study (Ng et al, 2008) in which Craig Venter’s genome was matched with the (in)famous [I love Watson] James Watson and focused on six genes that had to do with how people respond to antipsychotics, antidepressants, and other drugs. It was discovered that Venter had two of the ‘Caucasian’ variants whereas Watson carried variants more common in East Asians. Watson would have gotten the wrong medicine based on the assumption of his race and not on the predictive power of his own personal genome.

The author then talks about kidney disease and the fact that blacks are more likely to have it (Martins, Agodoa, and Norris, 2012). It was assumed that environmental factors caused the disparity of kidney disease in blacks when compared to whites, however then the APOL1 gene variant was discovered, which is related to worse kidney outcomes and is in higher frequencies in black Americans, even in blacks with well-controlled blood pressure (BP) (Parsa et al, 2013). The author then discusses that black kidneys were seen as ‘more prone to failure’ than white kidneys, but this is, so it’s said, due to that one specific gene variant and so, race shouldn’t be looked at in regards to kidney disease but individual genetic variation.

In one aspect of the medical community can using medicine based on one’s race help: prostate cancer. Black men are more likely to be afflicted with prostate cancer in comparison to whites (Odedina et al, 2009; Bhardwaj et al, 2017) with it even being proposed that black men should get separate prostate screenings to save more lives (Shenoy et al, 2016). Then he writes that we still don’t know the genes responsible, however, I have argued in the past that diet explains a large amount—if not all of the variance. (It’s not testosterone that causes it like Ross et al, 1986 believe).

The author then discusses another medical professional who argues that racial health disparities come down to the social environment. Things like BP could—most definitely—be driven by the social environment. It is assumed that the darker one’s skin is, the higher chance they have to have high BP—though this is not the case for Africans in Africa so this is clearly an American-only problem. I could conjure up one explanation: the darker the individual, the more likely he is to believe he is being ‘pre-judged’ which then affects his state of mind and has his BP rise. I discussed this shortly in my previous article Black-White Differences in Physiology. Williams (1992) reviewed evidence that social, not genetic, factors are responsible for BP differences between blacks and whites. He reviews one study showing that BP is higher in lower SES, darker-skinned blacks in comparison to higher SES blacks whereas for blacks with higher SES no effect was noticed (Klag et al, 1991). Sweet et al (2007) showed that for lighter-skinned blacks, as SES rose BP decreased while for darker-skinned blacks BP increased as SES did while implicating factors like ‘racism’ as the ultimate causes.

There is evidence for the effect of psychosocial factors and BP (Marmot, 1985). In a 2014 review of the literature, Cuffee et al (2014) identify less sleep—along with other psychosocial factors—as another cause of higher BP. It just so happens that blacks average about one hour of sleep less than whites. This could cause a lot of the variation in BP differences between the races, so clearly in the case of this variable, it is useful to know one’s race, along with their SES. Keep in mind that any actual ‘racism’ doesn’t have to occur; the person only ‘needs to perceive it’, and their blood BP will rise in response to the perceived ‘racism’ (Krieger and Sidney, 1996). Harburg et al (1978) write in regards to Detroit blacks:

For 35 blacks whose fathers were from the West Indies, pressures were higher than those with American-born fathers. These findings suggest that varied gene mixtures may be related to blood pressure levels and that skin color, an indicator of possible metabolic significance, combines with socially induced stress to induce higher blood pressures in lower class American blacks.

Langford (1981) shows that when SES differences are taken into account that the black-white BP disparity vanishes. So there seems to be good evidence for the hypothesis that psychosocial factors, sleep deprivation, diet and ‘perceived discrimination’ (whether real or imagined) can explain a lot of this gap so race and SES need to be looked at when BP is taken into account. These things are easily changeable; educate people on good diets, teach people that, in most cases, no, people are not being ‘racist’ against you. That’s really what it is. This effect holds more for darker-skinned, lower-class blacks. And while I don’t deny a small part of this could be due to genetic factors, the physiology of the heart and how BP is regulated by even perceptions is pretty powerful and could have a lot of explanatory power for numerous physiological differences between races and ethnic groups.

Krieger (1990) states that in black women—not in white women—“internalized response to unfair treatment, plus non-reporting of race and gender discrimination, may constitute risk factors for high blood pressure among black women“. This could come into play in regards to black-white female differences in BP. Thomson and Lip (2005) show that “environmental influence and psychosocial factors may play a more important role than is widely accepted” in hypertension but “There remain many uncertainties to the relative importance and contribution of environmental versus genetic influences on the development of blood pressure – there is more than likely an influence from both. However, there is now evidence to necessitate increased attention in examining the non-genetic influences on blood pressure …” With how our physiology evolved to respond to environmental stimuli and respond in real time to perceived threats, it is no wonder that these types of ‘perceived discrimination’ causes higher BP in certain groups with lower SES.

Wilson (1988) implicates salt as the reason why blacks have higher BP than whites. High salt intake could affect the body’s metabolism by causing salt retention which influences blood plasma volume, cardiac output. However, whites have a higher salt intake than blacks, but blacks still ate twice the recommended amounts from the dietary guidelines (all ethnic subgroups they analyzed from America over-consumed salt as well) (Fulgoni et al, 2014). Blacks are also more ‘salt-sensitive’ than whites (Sowers et al 1988; Schmidlin et al, 2009; Sanada, Jones, and Jose, 2014) which is also heritable in blacks (Svetke, McKeown, and Wilson, 1996). A slavery hypothesis does exist to explain higher rates of hypertension in blacks, citing salt deficiency in the parts of Africa that supplied the slaves to the Americas, to the trauma of the slave trade and slavery in America. However, historical evidence does not show this to be the case because “There is no evidence that diet or the resulting patterns of disease and demography among slaves in the American South were significantly different from those of other poor southerners” (Curtin, 1992) whereas Campese (1996) hypothesizes that blacks are more likely to get hypertension because they evolved in an area with low salt.

The NYT article concludes:

Science seeks to categorize nature, to sort it into discrete groupings to better understand it. That is one way to comprehend the race concept: as an honest scientific attempt to understand human variation. The problem is, the concept is imprecise. It has repeatedly slid toward pseudoscience and has become a major divider of humanity. Now, at a time when we desperately need ways to come together, there are scientists — intellectual descendants of the very people who helped give us the race concept — who want to retire it.

Race is a useful concept. Whether in medicine, population genetics, psychology, evolution, physiology, etc it can elucidate a lot of causes for differences between races and ethnic groups—whether or not they are genetic or psychosocial in nature. That just attests to both the power of suggestion along with psychosocial factors in regards to racial differences in physiological factors.

Finally let’s see what the literature says about race in medicine. Bonham et al (2009) showed that both black and white doctors concluded that race is medically relevant but couldn’t decide why however they did state that genetics did not explain most of the disparity in relation to race and disease aside from the obvious disorders like Tay Sachs and sickle cell anemia. Philosophers accept the usefulness of race in the biomedical sciences (Andreason, 2009; Efstathiou, 2012; Hardimon, 2013; Winther, Millstein, and Nielsen, 2015; Hardimon, 2017) whereas Risch et al (2002) and Tang et al (2002) concur that race is useful in the biomedical sciences. (See also Dorothy Roberts’ Ted Talk The problem with race-based medicine which I will cover in the future). Richard Lewontin, naturally, has hang-ups here but his contentions are taken care of above. Even if race were a ‘social construct‘, as Lewontin says, it would still be useful in a biomedical sense; but since there are differences between races/ethnic groups then they most definitely are useful in a biomedical sense, even if at the end of the day individual variation matters more than racial variation. Just knowing someone’s race and SES, for instance, can tell you a lot about possible maladies they may have, even if, utltimately, individual differences in physiology and anatomy matter more in regards to the biomedical context.

In conclusion, race is most definitely a useful concept in medicine, whether race is a ‘social construct’ or not. Just using Michael Hardimon’s race concepts, for instance, shows that race is extremely useful in the biomedical context, despite what naysayers may say. Yes, individual differences in anatomy and physiology trump racial differences, but just knowing a few things like race and SES can tell a lot about a particular person, for instance with blood pressure, resting metabolic rate, and so on. Denying that race is a useful concept in the biomedical sciences will lead to more—not less—racial health disparities, which is ironic because that’s exactly what race-deniers do not want. They will have to accept a race concept, and they would accept Hardimon’s socialrace concept because that still allows it to be a ‘social construct’ while acknowledging that race and psychosocial factors interact to cause higher physiological variables. Race is a useful concept in medicine, and if the medical establishment wants to save more lives and actually end the racial disparities in health then they should acknowledge the reality of race.

sometimes it is. most of the time it’s not.

LikeLike

How insightful.

LikeLike

leave the sarcasm to me please.

the point is that ALL info about a patient may be useful in one or more instances.

race is just one more bit of info which may assist in treatment on occasion.

for example, if it were known that blacks responded better to one drug than another on average then if one knows nothing about the patient’s genome except that he is black, one should prescribe the drug more effective in blacks.

so a better question might be: should any medical research be directed toward racial differences specifically or should such data always be merely incidental?

LikeLike