Home » 2017 (Page 15)

Yearly Archives: 2017

Why Are Humans Here?

1600 words

Why are humans here? No, I’m not going to talk about any gods being responsible for our placement on this planet, though some extraterrestrial phenomena do play a part in why we are here today. The story of how and why we are here is extremely fascinating, because we are here only by chance, not by any divine purpose.

To understand why we are here, we first need to know what we evolved from and where this organism evolved. The Burgess Shale is a limestone quarry formed after the events of the Cambrian explosion. In the Shale are the remnants of an ancient sea that had more varieties of life than today’s modern oceans. The Shale is the best record we have of Cambrian fossils after the Cambrian explosion we currently have. Preserved in the Shale are a wide variety of creatures. One of these creatures is our ancestor, the first chordate. It’s name: Pikaia gracilens.

Pikaia is the only fossil from the Burgess Shale we have found that is a direct ancestor of humans. Now think about the Burgess decimation and the odds of Pikaia surviving. If this one little one and a half inch organism didn’t survive the Burgess decimation, everything you see around you today would not be here. By chance, we humans are here today due to the very unlikely survival of Pikaia. Stephen Jay Gould wrote a whole book on the Burgess Shale and ended his book Wonderful Life: The Burgess Shale and the Nature of History (1989: 323) as follows:

And so, if you wish to ask the question of the ages—why do humans exist?—a major part of that answer, touching those aspects of the issue that science can touch at all, must be: because Pikaia survived the Burgess decimation. This response does not cite a single law of nature; it embodies no statement about predictable evolutionary pathways, no calculation of probabilities based on general rules of anatomy or ecology. The survival of Pikaia was a contingency of “just history.” I do not think that any “higher” answer can be given, and I cannot imagine that any resolution could be more fascinating.

The survival of organisms during a mass extinction may be strongly predicated by chance (Mayr, 1964: 121). The Burgess decimation is but one of five mass extinction events in earth’s history. Let’s say we could wind back life’s tape to the very beginning and let it play out again, at the end of the tape would we see something familiar or completely ‘alien’? I’m betting on it being something ‘alien’, since we know that the survival of certain organisms is paramount to why Man is here today. Indeed, biochemist Nick Lane and author of the book The Vital Question: Evolution and the Origins of Complex Life (2015) agrees and writes on page 21:

Given gravity, animals that fly are more likely to be lightweight, and possess something akin to wings. In a more general sense, it may be necessary for life to be cellular, composed of small units that keep their insides different from the outside world. If such constraints are dominant, life elsewhere may closely resemble life on earth. Conversely, perhaps contingency rules – the make-up of life depends on the random survivors of global accidents such as the asteroid impact that wiped out the dinosaurs. Wind back the clock to Cambrian times, half a billion years ago, when mammals first exploded into the fossil record, and let it play forwards again. Would that parallel be similar to our own? Perhaps the hills would be crawling with giant terrestrial octopuses.

I believe contingency does rule—we are the survivors of global accidents. Even survival during asteroid impact and its ensuing effects that killed the dinosaurs 65 million years ago was based on chance. The chance that the mammalian critters were small enough and could find enough sustenance to sustain themselves and survive while the big-bodied dinosaurs died out.

Let’s say one day someone discovers how to make a perfect representation in a lab that perfectly mimicked the conditions of the early earth down to the tee. Let’s also say that 1 month is equal to 1 billion years. In close to 5 months, the experiment will be finished. Will what we see in this experiment mirror what we see today, or will it be something completely different—completely alien? Stephen Jay Gould writes on page 323 of Wonderful Life:

Wind the tape of life back again to Burgess times, and let it play again. If Pikaia does not survive in the replay, we are wiped out of future history—all of us, from shark to robin to orangutan. And I don’t think that any handicapper, given Burgess evidence known today, would have granted very favorable odds for Pikaia.

Why should life play out the exact same way if we had the ability to wind back the tape of life?

Another aspect of our evolution and why we are here is the tiktaalik, the best representative for a “transtional species between fish and land-dwelling tetrapods“. Tiktaalik had the unique ability to prop itself up out of the water to scout for food and predators. Tiktaalik had the beginnings of beginnings of arms, what it used to prop itself up out of the water. Due to the way its fins were structured, it had the ability to walk on the seabed, and eventually land. This one ancestor of ours began to gain the ability to breathe air and transition to living on land. If all tiktaaliks had died out in a mass extinction, we, again, would not be here. The exclusion of certain organisms from history then excludes us from the future.

And now, of course, with talks of the how and why we are here, I must discuss the notion of ‘evolutionary progress‘. Surely, to say that there is any type of ‘progress’ to evolution based on the knowledge of certain organisms’ chance at survival seems very ludicrous. The commonly held notion of the ‘ladder of progress’, the scala naturae, is still prominent both in evolutionary biology and modern-day life. There is an implicit assumption that there must be some linear line from single-celled organisms to Man, and that we are the eventual culmination of the evolutionary process. However, if Pikaia had not survived the Burgess decimation, a lot of the animals you see around you today—including us—would not be here.

If dinosaurs had not died out, we would not be here today. That chance survival of small shrew-like mammals during the extinction event 65 mya is another reason why we are here. Stephen Jay Gould (1989) writes on page 318:

If mammals had arisen late and helped to drive dinosaurs to their doom, then we could legitamately propose a scenario of expected progress. But dinosaurs remained domininant and probably became extinct only as a quirky result of the most unpredictable of all events—a mass dying triggered by extraterrestrial impact. If dinosaurs had not died in this event, they would probably still dominate the large-bodied vertebrates, as they had for so long with such conspicuous success, and mammals would still be small creatures in the interstices of their world. This situation prevailed for one hundred million years, why not sixty million more? Since dinosaurs were not moving towards markedly larger brains, and since such a prospect may lay outside the capability of reptilian design (Jerison, 1973; Hopson, 1977), we must assume that consciousness would not have evolved on our planet if a cosmic catastrophe had not claimed the dinosaurs as victims. In an entirely literal sense, we owe our existence, as large reasoning mammals, to our lucky stars.

He also writes on page 320:

Run the tape again, and let the tiny twig of Homo sapiens expire in Africa. Other hominids may have stood on the threshhold of what we know as human possibilities, but many sensible scenarios would never generate our level of mentality. Run the tape again, and this time Neanderthal perishes in Europe, and Homo erectus in Asia (as they did in our world). The sole surviving stock, Homo erectus in Africa, stumbles along for a while, even prospers, but does not speciate and therefore remains stable. A mutated virus then wipes Homo erectus out, or a change in climate reconverts Africa into an inhospitable forest. One little twig on the mammalian branch, a lineage with interesting possibilities that were never realized, joins the vast majority of species in extinction. So what? Most possibilities are never realized, and who will know the difference?

Arguments of this form led me to the conclusion that biology’s most profound insight to human nature, status and potential lies in the simple phrase, the embodiment of contingency: Homo sapiens is an entity, not an idea.

In any type of rewind scenario, any little nudge, any little difference in the rewind would change the fate of the planet. Thusly, contingency rules.

So the answer to the question of why humans are here doesn’t have any mystical or religious answer. It’s as simple as “No Pikaia, no us.” Why we are here is highly predicated on chance and if any of our ancestors had died in the past, Homo sapiens would not be here today. Knowing what we know about the Burgess Shale shows how the concept of ‘progress’ in biology is ridiculous. Rewinding the tape of life will not lead to our existence again, and some other organism will rule the earth but it would not be us. The answer to why we are here is “just history”. I don’t think any other answer to the question is as interesting as cosmic and terrestrial accidents. That just makes our accomplishments as a species even more special.

How Does the Increasingly Diverse American Landscape Affect White Americans’ Racial Attitudes?

1700 words

Last month I wrote about how Trump won the election due to white Americans’ exposure to diversity caused them to support Trump and his anti-immigration policies over Clinton and Sanders. That is, whites high in racial/ethnic identification exposed to more diversity irrespective of political leaning would vote for Trump for President and not Clinton or Sanders. It is commonly said that more diversity will increase tolerance for the out-group, and all will be well. But is this true?

Craig and Richeson (2014) explored how the changing racial shift in America affects whites’ feelings towards the peoples replacing whites (‘Hispanic’/Latino populations) as well as the feelings of whites towards other minority groups that are not replacing them in the country. Interestingly, whites exposed to the racial shift group showed more pro-white, anti-minority violence as well as preferring spaces and interactions with their own kind over others. Moreover, negative feelings towards blacks and Asians were seen, two groups that are not replacing white Americans.

White Canadians who were exposed to a graph showing that whites would be a projected minority “perceived greater in-group threat” leading to the expression of “somewhat more anger toward and fear of racial minorities.” East Asians are showing the most population growth in Canada. Relaying this information to whites has them express less warmth towards East Asian Canadians.

In their first study (n=86, 44 shown the racial shift and 42 shown current U.S. demographics), participants who read the title of a newspaper provided to them. One paper was titled “In a Generation, Ethnic Minorities May Be the U.S. Majority”, whereas the other was titled “U.S. Census Bureau Releases New Estimates of the US Population by Ethnicity.” They were asked questions such as “I would rather work alongside people of my same ethnic origin,” and “It would bother me if my child married someone from a different ethnic background.” Whites who read the newspaper article showing ethnic replacement showed more racial bias than those who read about current U.S. demographics. Whites exposed to projected demographics were more likely to prefer settings and interactions with other whites compared to the group who read current demographics.

In study 2 a (n=28, 14 Dutch participants and 14 American participants, 14 exposed to the U.S. racial shift, 14 exposed to the Dutch racial shift), those in the U.S. racial shift category showed more pro-white/anti-Asian bias than participants in the Dutch racial shift category. Those who were exposed to the changing U.S. ethnic landscape were more likely to show pro-white/anti-black bias than participants exposed to the Dutch racial shift (study 2b, n=25, 14 U.S. racial shift, 11 Dutch racial shift). In other words, making the U.S changing racial/ethnic population important, whites showed that whites were, again, more likely to be pro-white and anti-minority, even while exposed to an important racial demographic shift in a foreign country (the Netherlands). Whites, then, exposed to more racial diversity will show more automatic bias towards minorities, especially whites who live around a lot of blacks and ‘Hispanics’. Making whites aware of the changing racial demographics in America had them express automatic racial bias towards all minority groups—even minority groups not responsible for the racial shift.

In study 3 (n=620, 317 women, 76.3% White, 9.0% Black, 10.0% Latino, 4.7% other race) whether attitudes toward different minority groups may be affected by the exposure to the racial shift. Study 3 specifically focused on whites (n=415, 212 women, median age 48.8, a nationally representative sample of white Americans). Half of the participants were shown information about the projected ethnic shift in America while the other half were given a news article on the geographic mobility in America (individuals who move in a given year). They were asked their feelings on the following statements:

“the American way of life is seriously threatened” and were asked to indicate their view of the trajectory of American society (1 = American society is getting much worse every year, 5 = American society is getting much better every year); these two items were standardized and averaged to create an index of system threat (r = .64). To assess system justification, we asked participants to indicate their agreement (1 = strongly agree, 7 = strongly disagree) to the statement “American society is set up so that people usually get what they deserve.”

They were also asked the following questions on how certain they were of America’s social future:

“If they increase in status, racial minorities are likely to reduce the influence of White Americans in society.” The racial identification question asked participants to indicate their agreement (1 = strongly agree, 7 = strongly disagree) with the following statement, “My opportunities in life are tied to those of my racial group as a whole.”

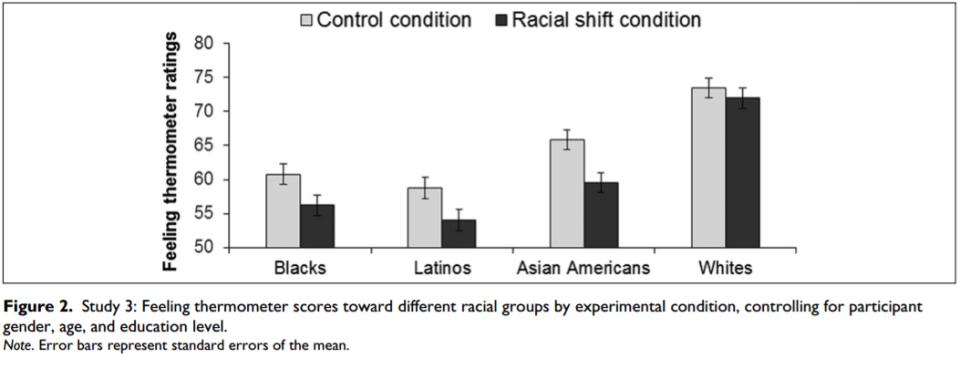

The researchers had the participants read the article about the impending racial shift in America and had them fill out “feeling thermometers” on how they felt about differing racial groups in America (blacks, whites, Asians and ‘Hispanics’) with 1 being cold and 100 being hot. Whites reported the most positivity towards their own group, followed by Asians, blacks and showing the least positivity towards ‘Hispanics’ (the group projected to replace whites in 25 years). Figure 2 also shows that whites don’t show the same negative biases they would towards other minorities in America, most likely due to the ‘model minority‘ status.

So the researchers showed that by making the racial shift important, that led to more white Americans showing negative attitudes towards minorities—specifically ‘Hispanics’. This was brought about by whites’ “concerns of lose of societal status.” When whites begin to notice demographic changes, the attitudes towards minorities will change—most notable the attitudes towards blacks and ‘Hispanics’ (which is due to the amount of crime committed by both groups, and is why whites show favoritism towards Asians, in my opinion). Overall, it was shown in a nationally representative sample of whites that showing the changing demographics in the country leads to more negative responses towards minority groups. This is due to the perceived threat on whites’ group status, which leads to more out-group bias.

These four studies report empirical evidence that contrary to the belief of liberals et al—that an increasingly diverse America will lead to more acceptance—more exposure to diversity and the changing racial demographics will have whites show more negative attitudes towards minority groups, most notably ‘Hispanics’, the group projected to become the majority by 2042. The authors write:

Consistent with this prior work, the present research offers compelling evidence that the impending so-called “majority-minority” U.S. population is construed by White Americans as a threat to their group’s position in society and increases their expression of racial bias on both automatically activated and selfreport attitude measures.

Interestingly, the authors also write:

That is, the article in the U.S. racial shift condition accurately attributed a large percentage of the population shift to increases in the Latino/Hispanic population, yet, participants in this condition expressed more negative attitudes toward Black Americans and Asian Americans (Study 3) as well as greater automatic bias on both a White-Asian and a White-Black IAT (Studies 2a and 2b). These findings suggest that the information often reported regarding the changing U.S. racial demographics may lead White Americans to perceive all racial minority groups as part of a monolithic non-White group.

You can see this from the rise of the alt-right. Whites, when exposed to the reality of the demographic shift in America, will begin to show more pro-white attitudes while derogating minority out-groups. It is important to note the implications of these studies. One could look at these studies, and rightly say, that as America becomes more diverse that ethnic tensions will increase. Indeed, this is what we are now currently seeing. Contrary to what people say about diversity “being our strength“, it will actually increase ethnic hostility in America and lead towards evermore increasing strife between ethnic groups in America (that is ever-rising due to the current political and social climate in the country). Diversity is not our “strength”—it is, in fact, the opposite. It is our weakness. As the country becomes more diverse we can expect more ethnic strife between groups, which will lower the quality of life for all ethnies, while making whites show more negative attitudes towards all minority groups (including Asians and blacks, but less so than ‘Hispanics’) due to group status threat. The authors write in the discussion:

That is, these studies revealed that White Americans for whom the U.S. racial demographic shift was made salient preferred interactions/settings with their own racial group over minority racial groups, expressed more automatic pro-White/antiminority bias, and expressed more negative attitudes toward Latinos, Blacks, and Asian Americans. The results of these latter studies also revealed that intergroup bias in response to the U.S. racial shift emerges toward racial/ethnic minority groups that are not primary contributors to the dramatic increases in the non-White (i.e., racial minority) population, namely, Blacks and Asian Americans. Moreover, this research provides the first evidence that automatic evaluations are affected by the perceived racial shift. Taken together, these findings suggest that rather than ushering in a more tolerant future, the increasing diversity of the nation may actually yield more intergroup hostility.

Thinking back to Rushton’s Genetic Similarity Theory, we can see why this occurs. Our genes are selfish and want to replicate with out similar genes. Thus, whites would become less tolerant of minority groups since they are less genetically similar to them. This would then be expressed in their attitudes towards minority groups—specifically, ‘Hispanics’ as that ethny will most likely to become the majority and overtake the white majority in 25 years. This is GST on steroids. Once whites realize the reality of the situation of increasing diversity in America—along with their status in the country as a whole—they will then show more negative bias towards minority out-groups.

All in all, the more whites are exposed to diversity in the social context as well as the reality of the ethnic demographic shift in 25 years will be more likely to show negative attitudes towards all American ethnies (though less negative attitudes towards Asians, dude to being less criminal, in my opinion). As the country becomes less white, so to will the whites in America become less tolerant of all minorities and start banding together for pro-white interests—showing that diversity is not our strength. This, in reality, is exactly what liberals do not want—whites banding together showing less favoritism towards the out-group. However, this is what occurs in countries that increasingly become diverse.

Neurons By Race

1100 words

With all of my recent articles on neurons and brain size, I’m now asking the following question: do neurons differ by race? The races of man differ on most all other variables, why not this one?

As we would have it, there are racial differences in total brain neurons.In 1970, an anti-hereditarian (Tobias) estimated the number of “excess neurons” available to different populations for processing bodily information, which Rushton (1988; 1997: 114) averaged to find: 8,550 for blacks, 8,660 for whites and 8,900 for Asians (in millions of excess neurons). A difference of 100-200 million neurons would be enough to explain away racial differences in achievement, for one. Two, these differences could also explain differences in intelligence. Rushton (1997: 133) writes:

This means that on this estimate, Mongoloids, who average 1,364 cm3 have 13.767 billion cortical neurons (13.767 x 109 ). Caucasoids who average 1,347 cm3 have 13.665 billion such neurons, 102 million less than Mongoloids. Negroids who average 1,267 cm3 , have 13.185 billion cerebral neurons, 582 million less than Mongoloids and 480 million less than Caucasoids.

Of course, Rushton’s citation of Jerison, I will leave alone now that we know that encephilazation quotient has problems. Rushton (1997: 133) writes:

The half-billion neuron difference between Mongoloids and Negroids are probably all “excess neurons” because, as mentioned, Mongoloids are often shorter in height and lighter in weight than Negroids. The Mongoloid-Negroid difference in brain size across so many estimation procedures is striking

Of course, small differences in brain size would translate to differences differences neuronal count (in the hundreds of millions), which would then affect intelligence.

Moreover, since whites have a greater volume in their prefrontal cortex (Vint, 1934). Using Herculano-Houzel’s favorite definition for intelligence, from MIT physicist Alex Wissner-Gross:

The ability to plan for the future, a significant function of prefrontal regions of the cortex, may be key indeed. According to the best definition I have come across so far, put forward by MIT physicist Alex Wissner-Gross, intelligence is the ability to make decisions that maximize future freedom of action—that is, decisions that keep most doors open for the future. (Herculano-Houzel, 2016: 122-123)

You can see the difference in behavior and action in the races; how one race has the ability to make decisions to maximize future ability of action—and those peoples with a smaller prefrontal cortex won’t have this ability (or it will be greatly hampered due to its small size and amount of neurons it has).

With a smaller, less developed frontal lobe and less overall neurons in it than a brain belonging to a European or Asian, this may then account for overall racial differences in intelligence. The few hundred million difference in neurons may be the missing piece to the puzzle here.Neurons transmit information to other nerves and muscle cells. Neurons have cell bodies, axons and dendrites. The more neurons (that’s also packed into a smaller brain, neuron packing density) in the brain, the better connectivity you have between different areas of the brain, allowing for fast reaction times (Asians beat whites who beat blacks, Rushton and Jensen, 2005: 240).

Remember how I said that the brain uses a certain amount of watts; well I’d assume that the different races would use differing amount of power for their brain due to differing number of neurons in them. Their brain is not as metabolically expensive. Larger brains are more intelligent than smaller brains ONLY BECAUSE there is a higher chance for there to be more neurons in the larger brain than the smaller one. With the average cranial capacity (blacks: 1267 cc, 13,185 million neurons; whites: 1347 cc, 13,665 million neurons, and Asians: 1,364, 13,767 million neurons). (Rushton and Jensen, 2005: 265, table 3) So as you can see, these differences are enough to account for racial differences in achievement.

A bigger brain would mean, more likely, more neurons which would then be able to power the brain and the body more efficiently. The more neurons one has, the more likely it it that they are intelligent as they have more neuronal pathways. The average cranial capcities of the races show that there are neuronal differences between them, which these neuronal differences then are the cause for racial differences, with the brain size itself being only a proxy, not an actual indicator of intelligence. The brain size doesn’t matter as much as the amount of neurons in the brain.

A difference in the brain of 100 grams is enough to account for 550 million cortical neurons (!!) (Jensen, 1998b: 438). But that ignores sex differences and neuronal density. However, I’d assume that there will be at least small differences in neuron count, especially from Rushton’s data from Race, Evolution and Behavior. Jensen (1998) also writes on page 439:

I have not found any investigation of racial differences in neuron density that, as in the case of sex differences, would offset the racial difference in brain weight or volume.

So neuronal density by brain weight is a great proxy.

Racial differences in intelligence don’t come down to brain size; they come down to total neuron amount in the brain; differences in size in certain parts of the brain critical to intelligence and amount of neurons in those critical portions of the brain. I’ve yet to come across a source talking about the different number of neurons in the brain by race, but when I do I will update this article. From what we know, we can make the assumption that blacks have less packing density as well as a smaller number of neurons in their PFC and cerebral cortex. Psychopathy is associated with abnormalities in the PFC; maybe, along with less intelligence, blacks would be more likely to be psychopathic? This also echoes what Richard Lynn says about Race and Psychopathic Personality:

There is a difference between blacks and whites—analogous to the difference in intelligence—in psychopathic personality considered as a personality trait. Both psychopathic personality and intelligence are bell curves with different means and distributions among blacks and whites. For intelligence, the mean and distribution are both lower among blacks. For psychopathic personality, the mean and distribution are higher among blacks. The effect of this is that there are more black psychopaths and more psychopathic behavior among blacks.

Neuronal differences and size of the PFC more than account for differences in psychopathy rates as well as differences in intelligence and scholastic achievement. This could, in part, explain the black-white IQ gap. Since the total number of neurons in the brain dictates, theoretically speaking, how well an organism can process information, and blacks have a smaller PFC (related to future time preference); and since blacks have less cortical neurons than Whites or Asians, this is one large reason why black are less intelligent, on average, than the other races of Man.

How Intelligent Were Our Hominin Ancestors?

3000 words

Tl;dr: Two of our most recent ancestors have IQs, theoretically speaking, near ours. This suggests that there were beneficial effects of cultural accumulation and transference. This also lends credence to Gould’s work in Full House, where he writes that “cultural change can vastly outstrip the maximal rate of Darwinian evolution.” Brain size may not have increased for IQ, but for expertise capacity. This is seen in the !Kung, gamblers at the horse track, chess players and musicians. There is both theoretical and empirical evidence that expertise needs large amounts of brain to store “and actively process its informational chunks.” These two studies in combination, in my opinion, shows how important the advent of ‘culture’ was for humans. Tool use got passed down as it gave us fitness advantages, then when Erectus discovered fire, that’s when the game changed. One of the first instances of cultural transference then happened, which set the stage for the rest of human evolution. Looking at it from this perspective, the importance of cultural inheritance and transference cannot be understated. It was due to that ‘behavioral change’ that allowed us all of the advantages we have over our ancestors; we have them to thank for everything we see around us today. For if not for them passing down the beginnings of culture that increased our fitness, individuals would have had to learn things for themselves which would decrease fitness. It’s due to this transference that we are here today.

My recent articles have consisted of what caused our big brains, whether or not there is ‘progress’ in hominin brain evolution, why humans are cognitively superior to other animals, and that the human brain is a linearly scaled-up primate brain (Herculano-Houzel, 2009). Knowing what we know about the human brain and the cellular scaling rules for primates (Herculano-Houzel, 2007), we can infer the amount of neurons that our ancestors Erectus, Heidelbergensis, and Neanderthals had. How intelligent were they? Does the EQ predict intelligence better for non-human primates, or does overall brain weight matter most? If our immediate ancestors had the same amount of neurons as we do, what does that mean for our supposed cognitive superiority over them?

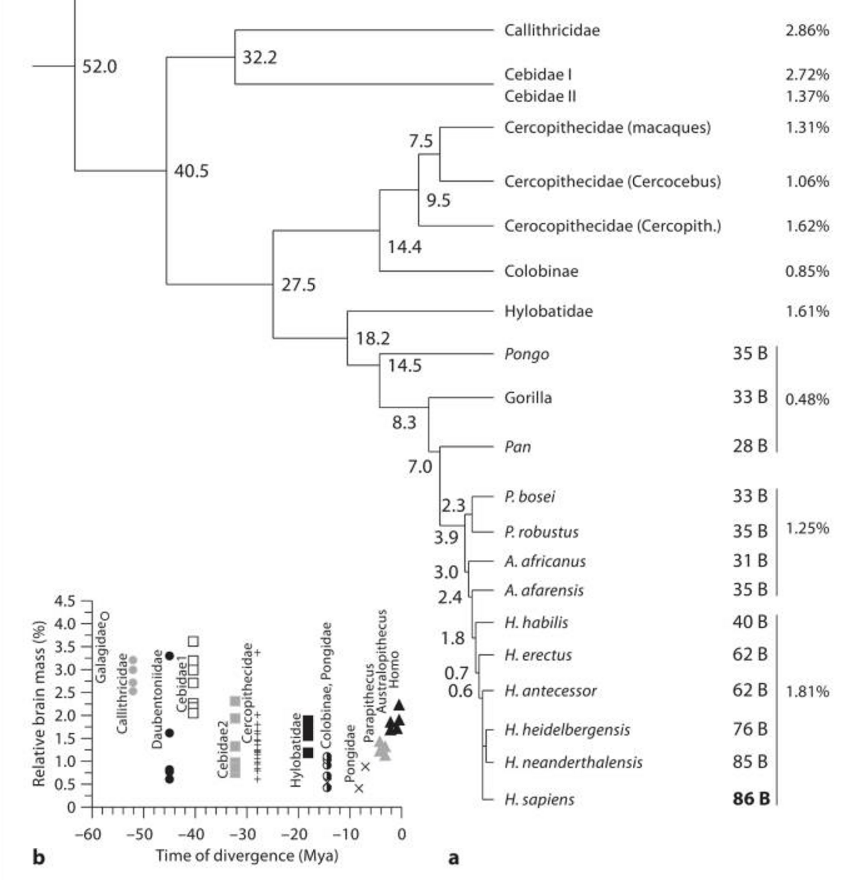

How many neurons did our ancestors have, and what did it mean for their intelligence levels? Herculano-Houzel (2013) estimated the amount of neurons that our ancestors had: Afarensis (35 b), Paranthropus (33 b), to close to 50-60 billion neurons in our species Homo from rudolfensis to antecessor, H. Erectus (62 b), Heidelbergensis (76 b), and Neanderthals (85 b), which is within the range for modern Sapiens. From our knowledge of the average human’s IQ (say, 100) and the total number of neurons the brain has (86 billion), what can we say about the IQs of Erectus, Afarensis, Paranthropus, rudolfensis, antecessor, Heidelbergensis, and Neanderthals?

(chart from Herculano-Houzel and Kaas, 2011)

Since Afarensis had about 35 billion neurons we can infer that his IQ was about 40. Paranthropus with about 33 billion neurons had an IQ of about 38. Homo habilis had 40 billion neurons, equating to IQ 46. Erectus with 62 billion neurons comes in at IQ 72., which differs with PP’s estimate by 22 points. (You can see the brain size increase [more on that later] and total neuron increase between habilis and erectus, with an almost 20 IQ point difference. The cause of this is the advent of cooking and the tool-use by habilis, named ‘Handy Man’.) Now we come to a problem. The total number of neurons in the brain of Heidelbergensis, Neanderthals, and humans are about the same.

Heidelbergensis had 76 billion neurons which equates to IQ 88. Neanderthals had about 85 billion neurons, equating to IQ 99. Our IQs are 100 with 86 billion neurons. As you can see, the leap from habilis (who may have eaten meat) to Erectus, a jump of 22 billion neurons and along with it 22. (The rise of bipedalism and tool use, fire, cooking, and meat eating led to the huge increase in neurons in our species Homo.) Then from Erectus to Heidelbergensis was a jump of 14 billion neurons along with an increase of 16 IQ points, then from Heidelbergensis to Neanderthal is an increase of 9 billion neurons, increasing IQ about 11 points. Neanderthals to us is about 1 billion neurons showing a difference of 1 IQ point.

This leads us to a troubling question: did Neanderthals and Hheidelbergensis at least have the capacity to become as intelligent as us? Herculano-Houzel and Kaas (2011) write:

Given that cognitive abilities of non-human primates are directly correlated with absolute brain size [Deaner et al., 2007], and hence necessarily to the total number of neurons in the brain, it is interesting to consider that enlarged brain size, consequence of an increased number of neurons in the brain, may itself have contributed to shedding a dependence on body size for successful competition for resources and mates, besides contributing with larger cognitive abilities towards the success of our species [Herculano-Houzel, 2009]. In this regard, it is tempting to speculate on our prediction that the modern range of number of neurons observed in the human brain [Azevedo et al., 2009] was already found in H. heidelbergensis and H. neanderthalensis, raising the intriguing possibility that they had similar cognitive potential to our species. Compared to their societies, our outstanding accomplishments as individuals, as groups, and as a species, in this scenario, would be witnesses of the beneficial effects of cultural accumulation and transmission over the ages.

If true, this is a huge finding as it echoes what Stephen Jay Gould wrote 21 years ago in his book Full House, as I documented in my article Stephen Jay Gould and Anti-Hereditarianism:

“The most impressive contrast between natural evolution and cultural evolution lies embedded in the major fact of our history. We have no evidence that the modal form of human bodies or brains has changed at all in the past 100,000 years—a standard phenomenon of stasis for successful and widespread species, and not (as popularly misconceived) an odd exception to an expectation of continuous and progressive change. The Cro-Magnon people who painted the caves of the Lascaux and Altamira some fifteen thousand years ago are us—and one look at the incredible richness and beauty of this work convinces us, in the most immediate and visceral way, that Picasso held no edge in mental sophistication over these ancestors with identical brains. And yet, fifteen thousand years ago no human social grouping had produced anything that would conform with our standard definition of civilization. No society had yet invented agriculture; none had built permanent cities. Everything that we have accomplished in the unmeasurable geological moment of the last ten thousand years—from the origin of agriculture to the Sears building in Chicago, the entire panoply of human civilization for better or for worse—has been built upon the capacities of an unaltered brain. Clearly, cultural change can vastly outstrip the maximal rate of natural Darwinian evolution.” (Gould, 1996: 220)

But human cultural change is an entirely distinct process operating under radically different principals that do allow for the strong possibility of a driven trend for what we may legitamately call “progress” (at least in a technological sense, whether or not the changes ultimately do us any good in a practical or moral way). In this sense, I deeply regret that common usage refers to the history of our artifacts and social orginizations as “cultural evolution.” Using the same term—evolution—for both natural and cultural history obfuscates far more than it enlightens. Of course, some aspects of the two phenomena must be similar, for all processes of genealogically constrained historical change must share some features in common. But the differences far outweigh the similarities in this case. Unfortunately, when we speak of “cultural evolution,” we unwittingly imply that this process shares essential similarity with the phenomenon most widely described by the same name—natural, or Darwinian, change. The common designation of “evolution” then leads to one of the most frequent and portentious errors in our analysis of human life and history—the overly reductionist assumption that the Darwinian natural paradigm will fully encompass our social and technological history as well. I do wish that the term “cultural evolution” would drop from use. Why not speak of something more neutral and descriptive—“cultural change,” for example? (Gould, 1996: 219-220)

The implications of the findings of the neuron count in Heidelbergensis and Neanderthals, if true, is a huge finding. Because it implies, as Herculano-Houzel and Kaas say, that “our outstanding accomplishments as individuals, as groups, and as a species … would be witnesses of the beneficial effects of cultural accumulation and transmission through the ages.” I’ve been thinking about this one sentence all week, racking my brain on what it could mean, while thinking about alternate possibilities.

I came across a paper by Dr. John Skoyles titled Human Evolution Expanded Brains to Increase Expertise, Not IQ (saying that around this part of the internet is the equivalent of heresy), in which he reviews studies of people living with microcephaly, showing that a lot of people who have the average brain size of Erectus have average, and even sometimes above average/genius IQs. Yes, microcephaly is correlated with retardation and low IQ, but a significant percentage of individuals inflicted with the disease showed average IQ scores (7 percent overall, 22 percent in 1 subgroup) (Skoyles, 1999). As I’ve documented in the past few days, Erectus was the hominin that learned how to control fire and kicked off the huge spurt in our brain growth. When this increase occurred, brain growth still had to happen outside of the brain, making the baby a fetus for one year after it is born. To achieve its larger brain size, the fetus must have a larger brain before birth, with it increasing postnatally.

The solution to this was to widen the hips of women. This would allow the birth canal to be ‘just right’ in terms of size so the baby could just barely make the squeeze. Physiological differences like this are why there are such huge sex differences in sports. Skoyles (1999) writes:

Research of three kinds suggests that small brained people can have normal IQs: (i) a recent MRI survey on brain size (Giedd et al. 1996), (ii) data on individuals born with microcephaly (head circumference 2 SD below the mean; Dorman, 1991); and (iii) data on early hemispherectomy (the removal of a dysfunctional cerebral hemisphere; Smith & Sugar, 1975; Griffith & Davidson, 1966; Vining et al., 1993).

He also writes that in a sample of 1006 school children, 2 percent (19 students) were found to be microcephalic. Of the 19 microcephalics, only 12 were in districts that did intelligence testing. Of the 12, 7 of them had an average IQ, with one having an IQ of 129. Skoyler even cites a study where a woman’s cranial capacity may have possibly been 760 cc (one the lower end of the range of Erectus brains)!! Her employment was described as ‘semi-skilled’, which Skoyler notes is normal for her ability level. Skoyler also says that Medline shows 21 other studies showing that microcephalic individuals have average IQs.

There is also one incidence of a man having a smaller brain than erectus while having a normal intelligence level, showing no peculiarities or mental retardation. Upon his death, his brain was weighed and they discovered that it weighed 624 grams!

Now, of course, the studies that Skoyler brings up are outliers, but they raise very interesting questions when you think about the supposed link with IQ and brain size. More interestingly, even sudden brain damage will leave a small change, if any, in IQ (Bigler, 1995). Finally, the .35 brain size-IQ correlation needs to be talked about. Let’s be generous and say the correlation is .5, 74 percent of the variance in IQ would still be unexplained (Skoyler, 1999: 8).

Skoyler then says that IQ tests “show very moderate to zero correlations with people’s ability to acquire expertise (Ackerman, 1996; Ceci & Liker, 1986; Doll & Mayr, 1987; Ericsson & Lehmann, 1996; Shuter-Dyson & Gabriel, 1981).” So he says that one’s capacity for expertise isn’t necessarily predicated on their IQ as measured by IQ tests. Skoyler writes:

Hence, whereas nonexpert players see only chess pieces, chess masters see possible future moves and potential strategies. Such in depth perception arises from acquiring and being able to actively use a larger numbers of informational “chunks” in analyzing a problem. The number of such chunks in chess masters has been estimated at 50,000 (Gobet & Simon, 1996). Such information processing chunks take many years to acquire. After reviewing performance in sport, medicine, chess and music, Ericsson and Lehmann (1996) propose that before people can show expertise in any domain they must have performed several hours of practice a day for a minimum of 10-years

So, this ‘expertise capacity’ seems to be a trained—not inherited—trait. He then cites a study on people who’ve spent decades at the daily race track betting on horse races. Cece and Liker (1986) measured the IQs of 12 of the experts, and found that they ranged between IQ 81 and 128 (“four were between 80 and 90, three between 90 and 100, two between 100 and 110 and only three above 120 Table 6”). The authors write: “whatever it is that an IQ test measures, it is not the ability to engage in cognitively complex forms of multivariate reasoning.” Moreover, Skoyler writes, expertise in chess (see Erickson, 2000) and music (see Deutsch, 1982: 404-405) “correlates poorly, or not at all with IQ.”

Now that we know that the capacity to develop expertise isn’t needed in the modern world, what did it mean for our hunter-gatherer ancestors? Looking at some of the few hunter-gatherer tribes left today, we can make some inferences.

The !Kung bushmen use in-depth expert knowledge and reasoning. Just by looking at a few tracks in the dirt, a bushman can infer whether the animal that made the track is sick, whether it was alone, its age and sex. They are able to do this by reading the shape and depth of the track in the dirt. Such skill, obviously, is learned, and those who didn’t have the capacity for expertise would have died out. Further, expertise in hunting is more important than physical ability, with the best hunters being over the age of 39 and not those in their 20s. This can further be seen when the young men go out for hunting. The young men do the physical work while the elder reads tracks, a learned ability.

This, Skoyler writes, suggests that those who had the highest capacity for expertise would have had the best chance for survival. Expertise in hunting is not the only thing that we need expertise for, obviously. The skill of ‘expertise’ translates to most all facets of human life. And over time, the advantages conferred by success with these activities “would result in the natural selection of brains with increased capacity for expertise.” So, even possibly, the success of our expertise could have selected for bigger brains which would have further increased the capacity for our expertise.

Since expertise is linked to the number of brain chunks that a brain can “hold and actively process”, that capacity for expertise “may be related to the number of cortical columns able to specialise neural networks in representing and processing them, and through this to cerebral mass Jerison (1991).” And, in brain scans of expert violinists, they have two to three times as much of their cortical area devoted to their left fingers as nonviolinists. ” This suggests that a strong connection should exist between the capacity for acquiring expertise skills and brain mass.”

I’m, of course, not denying the usefulness of IQ tests. What I’m saying, is that IQ tests don’t test a person’s capacity to learn a skill and become an expert in something. IQ tests, as shown, do not measure expertise capacity. IQ tests, then, don’t test for what was central to our evolution as hominins: expertise capacity. Of course, it’s not only expertise in hunting that led to the selection for bigger brains, and along with it expertise capacity. Obviously, this would hold for other things in our evolution that we can become experts in, from scavenging, to gathering, to language, social relationships, tool-making, and passing on useful skills that would infer an increase in fitness.

IQs for hominins are as follows: Paranthropus: IQ 38 (33 billion neurons); Afarensis: IQ 40 (35 billion neurons); Habilis: IQ 46 (40 billion neurons); Erectus: IQ 72 (62 billion neurons); Heidelbergensis: IQ 88 (76 billion neurons); Neanderthals: IQ 99 (85 billion neurons) and Sapiens: IQ 100 (85 billion neurons). So if Heidelbergensis and Neanderthals had IQs around ours (theoretically speaking), and Erectus had an IQ around modern-day Africans today, what explains our achievements over our hominin ancestors if we have around the same IQs?

Lamarckian cultural inheritance. If you think about when brain size began to increase, it was around the time that bipedalism occurred in the fossil record, along with tool use, fire, cooking, and meat eating. I’m suggesting here today that the beginnings of cultural transference happened with Afaraensis, Habilis, and Erectus. Passing down culture (useful traits for survival back then) would have been paramount in hominin survival. One wouldn’t have to learn how to do things on their own, and could learn from and elder the crucial survival skills they needed. This would have selected for a bigger brain due to the need for a higher expertise capacity, as with a bigger brain there is more room for cortical columns and neurons which would better facilitate expertise in that hominin.

I’m still thinking about what this all means, so I haven’t taken a side on this yet. This is an extremely interesting look into hominin brain size evolution, which shows that big brains didn’t evolve for IQ, but to increase expertise capacity. Though there is an extremely strong possibility that we gained over 20 billion neurons from Erectus due to his cooking, which then capped out our intelligence in our lineage. That would then mean that Neanderthals and Heidelbergensis would have had the capacity for the same IQ as us. One thing I can think of that set us apart 70 kya was the advent of art. That was a new way of transferring information from our hugely metabolically expensive neurons. This was also, yet another way of cultural transference. But what this means in terms of Neanderthal and Heidelbergensis IQ and what it means for our accomplishments since them is another story, which I will return to in the future.