Home » Posts tagged 'Evolution' (Page 6)

Tag Archives: Evolution

Why Are Humans Here?

1600 words

Why are humans here? No, I’m not going to talk about any gods being responsible for our placement on this planet, though some extraterrestrial phenomena do play a part in why we are here today. The story of how and why we are here is extremely fascinating, because we are here only by chance, not by any divine purpose.

To understand why we are here, we first need to know what we evolved from and where this organism evolved. The Burgess Shale is a limestone quarry formed after the events of the Cambrian explosion. In the Shale are the remnants of an ancient sea that had more varieties of life than today’s modern oceans. The Shale is the best record we have of Cambrian fossils after the Cambrian explosion we currently have. Preserved in the Shale are a wide variety of creatures. One of these creatures is our ancestor, the first chordate. It’s name: Pikaia gracilens.

Pikaia is the only fossil from the Burgess Shale we have found that is a direct ancestor of humans. Now think about the Burgess decimation and the odds of Pikaia surviving. If this one little one and a half inch organism didn’t survive the Burgess decimation, everything you see around you today would not be here. By chance, we humans are here today due to the very unlikely survival of Pikaia. Stephen Jay Gould wrote a whole book on the Burgess Shale and ended his book Wonderful Life: The Burgess Shale and the Nature of History (1989: 323) as follows:

And so, if you wish to ask the question of the ages—why do humans exist?—a major part of that answer, touching those aspects of the issue that science can touch at all, must be: because Pikaia survived the Burgess decimation. This response does not cite a single law of nature; it embodies no statement about predictable evolutionary pathways, no calculation of probabilities based on general rules of anatomy or ecology. The survival of Pikaia was a contingency of “just history.” I do not think that any “higher” answer can be given, and I cannot imagine that any resolution could be more fascinating.

The survival of organisms during a mass extinction may be strongly predicated by chance (Mayr, 1964: 121). The Burgess decimation is but one of five mass extinction events in earth’s history. Let’s say we could wind back life’s tape to the very beginning and let it play out again, at the end of the tape would we see something familiar or completely ‘alien’? I’m betting on it being something ‘alien’, since we know that the survival of certain organisms is paramount to why Man is here today. Indeed, biochemist Nick Lane and author of the book The Vital Question: Evolution and the Origins of Complex Life (2015) agrees and writes on page 21:

Given gravity, animals that fly are more likely to be lightweight, and possess something akin to wings. In a more general sense, it may be necessary for life to be cellular, composed of small units that keep their insides different from the outside world. If such constraints are dominant, life elsewhere may closely resemble life on earth. Conversely, perhaps contingency rules – the make-up of life depends on the random survivors of global accidents such as the asteroid impact that wiped out the dinosaurs. Wind back the clock to Cambrian times, half a billion years ago, when mammals first exploded into the fossil record, and let it play forwards again. Would that parallel be similar to our own? Perhaps the hills would be crawling with giant terrestrial octopuses.

I believe contingency does rule—we are the survivors of global accidents. Even survival during asteroid impact and its ensuing effects that killed the dinosaurs 65 million years ago was based on chance. The chance that the mammalian critters were small enough and could find enough sustenance to sustain themselves and survive while the big-bodied dinosaurs died out.

Let’s say one day someone discovers how to make a perfect representation in a lab that perfectly mimicked the conditions of the early earth down to the tee. Let’s also say that 1 month is equal to 1 billion years. In close to 5 months, the experiment will be finished. Will what we see in this experiment mirror what we see today, or will it be something completely different—completely alien? Stephen Jay Gould writes on page 323 of Wonderful Life:

Wind the tape of life back again to Burgess times, and let it play again. If Pikaia does not survive in the replay, we are wiped out of future history—all of us, from shark to robin to orangutan. And I don’t think that any handicapper, given Burgess evidence known today, would have granted very favorable odds for Pikaia.

Why should life play out the exact same way if we had the ability to wind back the tape of life?

Another aspect of our evolution and why we are here is the tiktaalik, the best representative for a “transtional species between fish and land-dwelling tetrapods“. Tiktaalik had the unique ability to prop itself up out of the water to scout for food and predators. Tiktaalik had the beginnings of beginnings of arms, what it used to prop itself up out of the water. Due to the way its fins were structured, it had the ability to walk on the seabed, and eventually land. This one ancestor of ours began to gain the ability to breathe air and transition to living on land. If all tiktaaliks had died out in a mass extinction, we, again, would not be here. The exclusion of certain organisms from history then excludes us from the future.

And now, of course, with talks of the how and why we are here, I must discuss the notion of ‘evolutionary progress‘. Surely, to say that there is any type of ‘progress’ to evolution based on the knowledge of certain organisms’ chance at survival seems very ludicrous. The commonly held notion of the ‘ladder of progress’, the scala naturae, is still prominent both in evolutionary biology and modern-day life. There is an implicit assumption that there must be some linear line from single-celled organisms to Man, and that we are the eventual culmination of the evolutionary process. However, if Pikaia had not survived the Burgess decimation, a lot of the animals you see around you today—including us—would not be here.

If dinosaurs had not died out, we would not be here today. That chance survival of small shrew-like mammals during the extinction event 65 mya is another reason why we are here. Stephen Jay Gould (1989) writes on page 318:

If mammals had arisen late and helped to drive dinosaurs to their doom, then we could legitamately propose a scenario of expected progress. But dinosaurs remained domininant and probably became extinct only as a quirky result of the most unpredictable of all events—a mass dying triggered by extraterrestrial impact. If dinosaurs had not died in this event, they would probably still dominate the large-bodied vertebrates, as they had for so long with such conspicuous success, and mammals would still be small creatures in the interstices of their world. This situation prevailed for one hundred million years, why not sixty million more? Since dinosaurs were not moving towards markedly larger brains, and since such a prospect may lay outside the capability of reptilian design (Jerison, 1973; Hopson, 1977), we must assume that consciousness would not have evolved on our planet if a cosmic catastrophe had not claimed the dinosaurs as victims. In an entirely literal sense, we owe our existence, as large reasoning mammals, to our lucky stars.

He also writes on page 320:

Run the tape again, and let the tiny twig of Homo sapiens expire in Africa. Other hominids may have stood on the threshhold of what we know as human possibilities, but many sensible scenarios would never generate our level of mentality. Run the tape again, and this time Neanderthal perishes in Europe, and Homo erectus in Asia (as they did in our world). The sole surviving stock, Homo erectus in Africa, stumbles along for a while, even prospers, but does not speciate and therefore remains stable. A mutated virus then wipes Homo erectus out, or a change in climate reconverts Africa into an inhospitable forest. One little twig on the mammalian branch, a lineage with interesting possibilities that were never realized, joins the vast majority of species in extinction. So what? Most possibilities are never realized, and who will know the difference?

Arguments of this form led me to the conclusion that biology’s most profound insight to human nature, status and potential lies in the simple phrase, the embodiment of contingency: Homo sapiens is an entity, not an idea.

In any type of rewind scenario, any little nudge, any little difference in the rewind would change the fate of the planet. Thusly, contingency rules.

So the answer to the question of why humans are here doesn’t have any mystical or religious answer. It’s as simple as “No Pikaia, no us.” Why we are here is highly predicated on chance and if any of our ancestors had died in the past, Homo sapiens would not be here today. Knowing what we know about the Burgess Shale shows how the concept of ‘progress’ in biology is ridiculous. Rewinding the tape of life will not lead to our existence again, and some other organism will rule the earth but it would not be us. The answer to why we are here is “just history”. I don’t think any other answer to the question is as interesting as cosmic and terrestrial accidents. That just makes our accomplishments as a species even more special.

Neurons By Race

1100 words

With all of my recent articles on neurons and brain size, I’m now asking the following question: do neurons differ by race? The races of man differ on most all other variables, why not this one?

As we would have it, there are racial differences in total brain neurons.In 1970, an anti-hereditarian (Tobias) estimated the number of “excess neurons” available to different populations for processing bodily information, which Rushton (1988; 1997: 114) averaged to find: 8,550 for blacks, 8,660 for whites and 8,900 for Asians (in millions of excess neurons). A difference of 100-200 million neurons would be enough to explain away racial differences in achievement, for one. Two, these differences could also explain differences in intelligence. Rushton (1997: 133) writes:

This means that on this estimate, Mongoloids, who average 1,364 cm3 have 13.767 billion cortical neurons (13.767 x 109 ). Caucasoids who average 1,347 cm3 have 13.665 billion such neurons, 102 million less than Mongoloids. Negroids who average 1,267 cm3 , have 13.185 billion cerebral neurons, 582 million less than Mongoloids and 480 million less than Caucasoids.

Of course, Rushton’s citation of Jerison, I will leave alone now that we know that encephilazation quotient has problems. Rushton (1997: 133) writes:

The half-billion neuron difference between Mongoloids and Negroids are probably all “excess neurons” because, as mentioned, Mongoloids are often shorter in height and lighter in weight than Negroids. The Mongoloid-Negroid difference in brain size across so many estimation procedures is striking

Of course, small differences in brain size would translate to differences differences neuronal count (in the hundreds of millions), which would then affect intelligence.

Moreover, since whites have a greater volume in their prefrontal cortex (Vint, 1934). Using Herculano-Houzel’s favorite definition for intelligence, from MIT physicist Alex Wissner-Gross:

The ability to plan for the future, a significant function of prefrontal regions of the cortex, may be key indeed. According to the best definition I have come across so far, put forward by MIT physicist Alex Wissner-Gross, intelligence is the ability to make decisions that maximize future freedom of action—that is, decisions that keep most doors open for the future. (Herculano-Houzel, 2016: 122-123)

You can see the difference in behavior and action in the races; how one race has the ability to make decisions to maximize future ability of action—and those peoples with a smaller prefrontal cortex won’t have this ability (or it will be greatly hampered due to its small size and amount of neurons it has).

With a smaller, less developed frontal lobe and less overall neurons in it than a brain belonging to a European or Asian, this may then account for overall racial differences in intelligence. The few hundred million difference in neurons may be the missing piece to the puzzle here.Neurons transmit information to other nerves and muscle cells. Neurons have cell bodies, axons and dendrites. The more neurons (that’s also packed into a smaller brain, neuron packing density) in the brain, the better connectivity you have between different areas of the brain, allowing for fast reaction times (Asians beat whites who beat blacks, Rushton and Jensen, 2005: 240).

Remember how I said that the brain uses a certain amount of watts; well I’d assume that the different races would use differing amount of power for their brain due to differing number of neurons in them. Their brain is not as metabolically expensive. Larger brains are more intelligent than smaller brains ONLY BECAUSE there is a higher chance for there to be more neurons in the larger brain than the smaller one. With the average cranial capacity (blacks: 1267 cc, 13,185 million neurons; whites: 1347 cc, 13,665 million neurons, and Asians: 1,364, 13,767 million neurons). (Rushton and Jensen, 2005: 265, table 3) So as you can see, these differences are enough to account for racial differences in achievement.

A bigger brain would mean, more likely, more neurons which would then be able to power the brain and the body more efficiently. The more neurons one has, the more likely it it that they are intelligent as they have more neuronal pathways. The average cranial capcities of the races show that there are neuronal differences between them, which these neuronal differences then are the cause for racial differences, with the brain size itself being only a proxy, not an actual indicator of intelligence. The brain size doesn’t matter as much as the amount of neurons in the brain.

A difference in the brain of 100 grams is enough to account for 550 million cortical neurons (!!) (Jensen, 1998b: 438). But that ignores sex differences and neuronal density. However, I’d assume that there will be at least small differences in neuron count, especially from Rushton’s data from Race, Evolution and Behavior. Jensen (1998) also writes on page 439:

I have not found any investigation of racial differences in neuron density that, as in the case of sex differences, would offset the racial difference in brain weight or volume.

So neuronal density by brain weight is a great proxy.

Racial differences in intelligence don’t come down to brain size; they come down to total neuron amount in the brain; differences in size in certain parts of the brain critical to intelligence and amount of neurons in those critical portions of the brain. I’ve yet to come across a source talking about the different number of neurons in the brain by race, but when I do I will update this article. From what we know, we can make the assumption that blacks have less packing density as well as a smaller number of neurons in their PFC and cerebral cortex. Psychopathy is associated with abnormalities in the PFC; maybe, along with less intelligence, blacks would be more likely to be psychopathic? This also echoes what Richard Lynn says about Race and Psychopathic Personality:

There is a difference between blacks and whites—analogous to the difference in intelligence—in psychopathic personality considered as a personality trait. Both psychopathic personality and intelligence are bell curves with different means and distributions among blacks and whites. For intelligence, the mean and distribution are both lower among blacks. For psychopathic personality, the mean and distribution are higher among blacks. The effect of this is that there are more black psychopaths and more psychopathic behavior among blacks.

Neuronal differences and size of the PFC more than account for differences in psychopathy rates as well as differences in intelligence and scholastic achievement. This could, in part, explain the black-white IQ gap. Since the total number of neurons in the brain dictates, theoretically speaking, how well an organism can process information, and blacks have a smaller PFC (related to future time preference); and since blacks have less cortical neurons than Whites or Asians, this is one large reason why black are less intelligent, on average, than the other races of Man.

How Intelligent Were Our Hominin Ancestors?

3000 words

Tl;dr: Two of our most recent ancestors have IQs, theoretically speaking, near ours. This suggests that there were beneficial effects of cultural accumulation and transference. This also lends credence to Gould’s work in Full House, where he writes that “cultural change can vastly outstrip the maximal rate of Darwinian evolution.” Brain size may not have increased for IQ, but for expertise capacity. This is seen in the !Kung, gamblers at the horse track, chess players and musicians. There is both theoretical and empirical evidence that expertise needs large amounts of brain to store “and actively process its informational chunks.” These two studies in combination, in my opinion, shows how important the advent of ‘culture’ was for humans. Tool use got passed down as it gave us fitness advantages, then when Erectus discovered fire, that’s when the game changed. One of the first instances of cultural transference then happened, which set the stage for the rest of human evolution. Looking at it from this perspective, the importance of cultural inheritance and transference cannot be understated. It was due to that ‘behavioral change’ that allowed us all of the advantages we have over our ancestors; we have them to thank for everything we see around us today. For if not for them passing down the beginnings of culture that increased our fitness, individuals would have had to learn things for themselves which would decrease fitness. It’s due to this transference that we are here today.

My recent articles have consisted of what caused our big brains, whether or not there is ‘progress’ in hominin brain evolution, why humans are cognitively superior to other animals, and that the human brain is a linearly scaled-up primate brain (Herculano-Houzel, 2009). Knowing what we know about the human brain and the cellular scaling rules for primates (Herculano-Houzel, 2007), we can infer the amount of neurons that our ancestors Erectus, Heidelbergensis, and Neanderthals had. How intelligent were they? Does the EQ predict intelligence better for non-human primates, or does overall brain weight matter most? If our immediate ancestors had the same amount of neurons as we do, what does that mean for our supposed cognitive superiority over them?

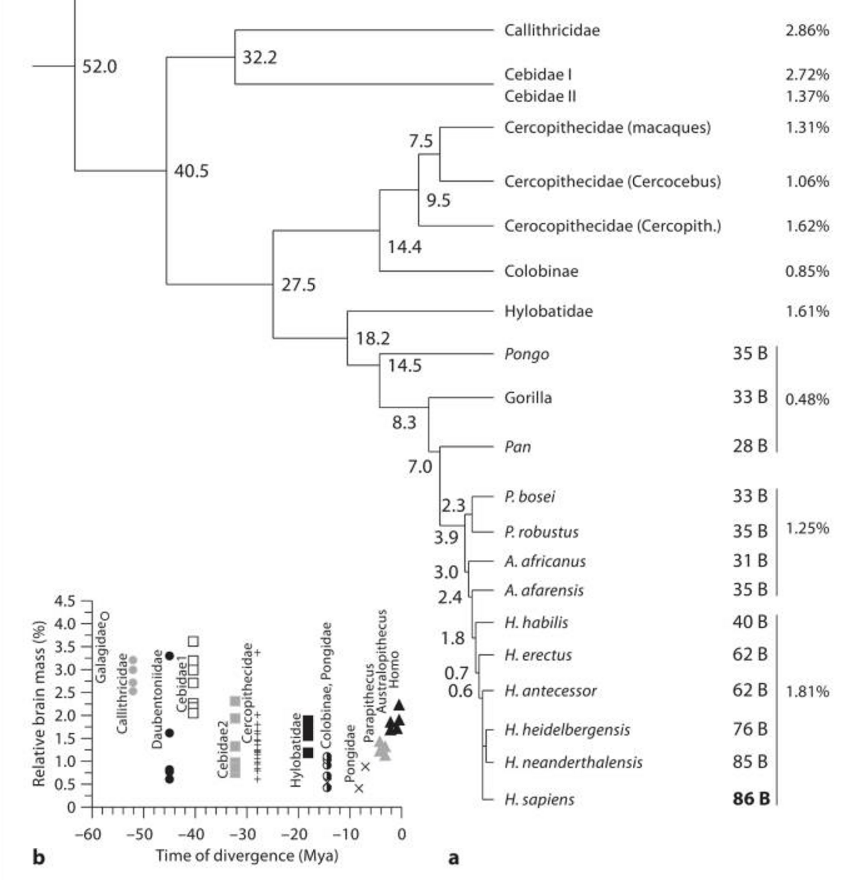

How many neurons did our ancestors have, and what did it mean for their intelligence levels? Herculano-Houzel (2013) estimated the amount of neurons that our ancestors had: Afarensis (35 b), Paranthropus (33 b), to close to 50-60 billion neurons in our species Homo from rudolfensis to antecessor, H. Erectus (62 b), Heidelbergensis (76 b), and Neanderthals (85 b), which is within the range for modern Sapiens. From our knowledge of the average human’s IQ (say, 100) and the total number of neurons the brain has (86 billion), what can we say about the IQs of Erectus, Afarensis, Paranthropus, rudolfensis, antecessor, Heidelbergensis, and Neanderthals?

(chart from Herculano-Houzel and Kaas, 2011)

Since Afarensis had about 35 billion neurons we can infer that his IQ was about 40. Paranthropus with about 33 billion neurons had an IQ of about 38. Homo habilis had 40 billion neurons, equating to IQ 46. Erectus with 62 billion neurons comes in at IQ 72., which differs with PP’s estimate by 22 points. (You can see the brain size increase [more on that later] and total neuron increase between habilis and erectus, with an almost 20 IQ point difference. The cause of this is the advent of cooking and the tool-use by habilis, named ‘Handy Man’.) Now we come to a problem. The total number of neurons in the brain of Heidelbergensis, Neanderthals, and humans are about the same.

Heidelbergensis had 76 billion neurons which equates to IQ 88. Neanderthals had about 85 billion neurons, equating to IQ 99. Our IQs are 100 with 86 billion neurons. As you can see, the leap from habilis (who may have eaten meat) to Erectus, a jump of 22 billion neurons and along with it 22. (The rise of bipedalism and tool use, fire, cooking, and meat eating led to the huge increase in neurons in our species Homo.) Then from Erectus to Heidelbergensis was a jump of 14 billion neurons along with an increase of 16 IQ points, then from Heidelbergensis to Neanderthal is an increase of 9 billion neurons, increasing IQ about 11 points. Neanderthals to us is about 1 billion neurons showing a difference of 1 IQ point.

This leads us to a troubling question: did Neanderthals and Hheidelbergensis at least have the capacity to become as intelligent as us? Herculano-Houzel and Kaas (2011) write:

Given that cognitive abilities of non-human primates are directly correlated with absolute brain size [Deaner et al., 2007], and hence necessarily to the total number of neurons in the brain, it is interesting to consider that enlarged brain size, consequence of an increased number of neurons in the brain, may itself have contributed to shedding a dependence on body size for successful competition for resources and mates, besides contributing with larger cognitive abilities towards the success of our species [Herculano-Houzel, 2009]. In this regard, it is tempting to speculate on our prediction that the modern range of number of neurons observed in the human brain [Azevedo et al., 2009] was already found in H. heidelbergensis and H. neanderthalensis, raising the intriguing possibility that they had similar cognitive potential to our species. Compared to their societies, our outstanding accomplishments as individuals, as groups, and as a species, in this scenario, would be witnesses of the beneficial effects of cultural accumulation and transmission over the ages.

If true, this is a huge finding as it echoes what Stephen Jay Gould wrote 21 years ago in his book Full House, as I documented in my article Stephen Jay Gould and Anti-Hereditarianism:

“The most impressive contrast between natural evolution and cultural evolution lies embedded in the major fact of our history. We have no evidence that the modal form of human bodies or brains has changed at all in the past 100,000 years—a standard phenomenon of stasis for successful and widespread species, and not (as popularly misconceived) an odd exception to an expectation of continuous and progressive change. The Cro-Magnon people who painted the caves of the Lascaux and Altamira some fifteen thousand years ago are us—and one look at the incredible richness and beauty of this work convinces us, in the most immediate and visceral way, that Picasso held no edge in mental sophistication over these ancestors with identical brains. And yet, fifteen thousand years ago no human social grouping had produced anything that would conform with our standard definition of civilization. No society had yet invented agriculture; none had built permanent cities. Everything that we have accomplished in the unmeasurable geological moment of the last ten thousand years—from the origin of agriculture to the Sears building in Chicago, the entire panoply of human civilization for better or for worse—has been built upon the capacities of an unaltered brain. Clearly, cultural change can vastly outstrip the maximal rate of natural Darwinian evolution.” (Gould, 1996: 220)

But human cultural change is an entirely distinct process operating under radically different principals that do allow for the strong possibility of a driven trend for what we may legitamately call “progress” (at least in a technological sense, whether or not the changes ultimately do us any good in a practical or moral way). In this sense, I deeply regret that common usage refers to the history of our artifacts and social orginizations as “cultural evolution.” Using the same term—evolution—for both natural and cultural history obfuscates far more than it enlightens. Of course, some aspects of the two phenomena must be similar, for all processes of genealogically constrained historical change must share some features in common. But the differences far outweigh the similarities in this case. Unfortunately, when we speak of “cultural evolution,” we unwittingly imply that this process shares essential similarity with the phenomenon most widely described by the same name—natural, or Darwinian, change. The common designation of “evolution” then leads to one of the most frequent and portentious errors in our analysis of human life and history—the overly reductionist assumption that the Darwinian natural paradigm will fully encompass our social and technological history as well. I do wish that the term “cultural evolution” would drop from use. Why not speak of something more neutral and descriptive—“cultural change,” for example? (Gould, 1996: 219-220)

The implications of the findings of the neuron count in Heidelbergensis and Neanderthals, if true, is a huge finding. Because it implies, as Herculano-Houzel and Kaas say, that “our outstanding accomplishments as individuals, as groups, and as a species … would be witnesses of the beneficial effects of cultural accumulation and transmission through the ages.” I’ve been thinking about this one sentence all week, racking my brain on what it could mean, while thinking about alternate possibilities.

I came across a paper by Dr. John Skoyles titled Human Evolution Expanded Brains to Increase Expertise, Not IQ (saying that around this part of the internet is the equivalent of heresy), in which he reviews studies of people living with microcephaly, showing that a lot of people who have the average brain size of Erectus have average, and even sometimes above average/genius IQs. Yes, microcephaly is correlated with retardation and low IQ, but a significant percentage of individuals inflicted with the disease showed average IQ scores (7 percent overall, 22 percent in 1 subgroup) (Skoyles, 1999). As I’ve documented in the past few days, Erectus was the hominin that learned how to control fire and kicked off the huge spurt in our brain growth. When this increase occurred, brain growth still had to happen outside of the brain, making the baby a fetus for one year after it is born. To achieve its larger brain size, the fetus must have a larger brain before birth, with it increasing postnatally.

The solution to this was to widen the hips of women. This would allow the birth canal to be ‘just right’ in terms of size so the baby could just barely make the squeeze. Physiological differences like this are why there are such huge sex differences in sports. Skoyles (1999) writes:

Research of three kinds suggests that small brained people can have normal IQs: (i) a recent MRI survey on brain size (Giedd et al. 1996), (ii) data on individuals born with microcephaly (head circumference 2 SD below the mean; Dorman, 1991); and (iii) data on early hemispherectomy (the removal of a dysfunctional cerebral hemisphere; Smith & Sugar, 1975; Griffith & Davidson, 1966; Vining et al., 1993).

He also writes that in a sample of 1006 school children, 2 percent (19 students) were found to be microcephalic. Of the 19 microcephalics, only 12 were in districts that did intelligence testing. Of the 12, 7 of them had an average IQ, with one having an IQ of 129. Skoyler even cites a study where a woman’s cranial capacity may have possibly been 760 cc (one the lower end of the range of Erectus brains)!! Her employment was described as ‘semi-skilled’, which Skoyler notes is normal for her ability level. Skoyler also says that Medline shows 21 other studies showing that microcephalic individuals have average IQs.

There is also one incidence of a man having a smaller brain than erectus while having a normal intelligence level, showing no peculiarities or mental retardation. Upon his death, his brain was weighed and they discovered that it weighed 624 grams!

Now, of course, the studies that Skoyler brings up are outliers, but they raise very interesting questions when you think about the supposed link with IQ and brain size. More interestingly, even sudden brain damage will leave a small change, if any, in IQ (Bigler, 1995). Finally, the .35 brain size-IQ correlation needs to be talked about. Let’s be generous and say the correlation is .5, 74 percent of the variance in IQ would still be unexplained (Skoyler, 1999: 8).

Skoyler then says that IQ tests “show very moderate to zero correlations with people’s ability to acquire expertise (Ackerman, 1996; Ceci & Liker, 1986; Doll & Mayr, 1987; Ericsson & Lehmann, 1996; Shuter-Dyson & Gabriel, 1981).” So he says that one’s capacity for expertise isn’t necessarily predicated on their IQ as measured by IQ tests. Skoyler writes:

Hence, whereas nonexpert players see only chess pieces, chess masters see possible future moves and potential strategies. Such in depth perception arises from acquiring and being able to actively use a larger numbers of informational “chunks” in analyzing a problem. The number of such chunks in chess masters has been estimated at 50,000 (Gobet & Simon, 1996). Such information processing chunks take many years to acquire. After reviewing performance in sport, medicine, chess and music, Ericsson and Lehmann (1996) propose that before people can show expertise in any domain they must have performed several hours of practice a day for a minimum of 10-years

So, this ‘expertise capacity’ seems to be a trained—not inherited—trait. He then cites a study on people who’ve spent decades at the daily race track betting on horse races. Cece and Liker (1986) measured the IQs of 12 of the experts, and found that they ranged between IQ 81 and 128 (“four were between 80 and 90, three between 90 and 100, two between 100 and 110 and only three above 120 Table 6”). The authors write: “whatever it is that an IQ test measures, it is not the ability to engage in cognitively complex forms of multivariate reasoning.” Moreover, Skoyler writes, expertise in chess (see Erickson, 2000) and music (see Deutsch, 1982: 404-405) “correlates poorly, or not at all with IQ.”

Now that we know that the capacity to develop expertise isn’t needed in the modern world, what did it mean for our hunter-gatherer ancestors? Looking at some of the few hunter-gatherer tribes left today, we can make some inferences.

The !Kung bushmen use in-depth expert knowledge and reasoning. Just by looking at a few tracks in the dirt, a bushman can infer whether the animal that made the track is sick, whether it was alone, its age and sex. They are able to do this by reading the shape and depth of the track in the dirt. Such skill, obviously, is learned, and those who didn’t have the capacity for expertise would have died out. Further, expertise in hunting is more important than physical ability, with the best hunters being over the age of 39 and not those in their 20s. This can further be seen when the young men go out for hunting. The young men do the physical work while the elder reads tracks, a learned ability.

This, Skoyler writes, suggests that those who had the highest capacity for expertise would have had the best chance for survival. Expertise in hunting is not the only thing that we need expertise for, obviously. The skill of ‘expertise’ translates to most all facets of human life. And over time, the advantages conferred by success with these activities “would result in the natural selection of brains with increased capacity for expertise.” So, even possibly, the success of our expertise could have selected for bigger brains which would have further increased the capacity for our expertise.

Since expertise is linked to the number of brain chunks that a brain can “hold and actively process”, that capacity for expertise “may be related to the number of cortical columns able to specialise neural networks in representing and processing them, and through this to cerebral mass Jerison (1991).” And, in brain scans of expert violinists, they have two to three times as much of their cortical area devoted to their left fingers as nonviolinists. ” This suggests that a strong connection should exist between the capacity for acquiring expertise skills and brain mass.”

I’m, of course, not denying the usefulness of IQ tests. What I’m saying, is that IQ tests don’t test a person’s capacity to learn a skill and become an expert in something. IQ tests, as shown, do not measure expertise capacity. IQ tests, then, don’t test for what was central to our evolution as hominins: expertise capacity. Of course, it’s not only expertise in hunting that led to the selection for bigger brains, and along with it expertise capacity. Obviously, this would hold for other things in our evolution that we can become experts in, from scavenging, to gathering, to language, social relationships, tool-making, and passing on useful skills that would infer an increase in fitness.

IQs for hominins are as follows: Paranthropus: IQ 38 (33 billion neurons); Afarensis: IQ 40 (35 billion neurons); Habilis: IQ 46 (40 billion neurons); Erectus: IQ 72 (62 billion neurons); Heidelbergensis: IQ 88 (76 billion neurons); Neanderthals: IQ 99 (85 billion neurons) and Sapiens: IQ 100 (85 billion neurons). So if Heidelbergensis and Neanderthals had IQs around ours (theoretically speaking), and Erectus had an IQ around modern-day Africans today, what explains our achievements over our hominin ancestors if we have around the same IQs?

Lamarckian cultural inheritance. If you think about when brain size began to increase, it was around the time that bipedalism occurred in the fossil record, along with tool use, fire, cooking, and meat eating. I’m suggesting here today that the beginnings of cultural transference happened with Afaraensis, Habilis, and Erectus. Passing down culture (useful traits for survival back then) would have been paramount in hominin survival. One wouldn’t have to learn how to do things on their own, and could learn from and elder the crucial survival skills they needed. This would have selected for a bigger brain due to the need for a higher expertise capacity, as with a bigger brain there is more room for cortical columns and neurons which would better facilitate expertise in that hominin.

I’m still thinking about what this all means, so I haven’t taken a side on this yet. This is an extremely interesting look into hominin brain size evolution, which shows that big brains didn’t evolve for IQ, but to increase expertise capacity. Though there is an extremely strong possibility that we gained over 20 billion neurons from Erectus due to his cooking, which then capped out our intelligence in our lineage. That would then mean that Neanderthals and Heidelbergensis would have had the capacity for the same IQ as us. One thing I can think of that set us apart 70 kya was the advent of art. That was a new way of transferring information from our hugely metabolically expensive neurons. This was also, yet another way of cultural transference. But what this means in terms of Neanderthal and Heidelbergensis IQ and what it means for our accomplishments since them is another story, which I will return to in the future.

Why Are Humans Cognitively Superior to Other Animals?

1550 words

The past few articles I have written touched on the fact that the human brain isn’t special and is just a scaled-up primate brain, bipedalism, tools, fire, cooking and meat eating had the largest effect on hominin brain evolution, and that, despite seeing a so-called ‘upward trend’ in the evolution of primate brain size, the reverse was occurring. So what makes us cognitively superior to other animals?

The most oft-cited reason why humans are cognitively superior to other animals is that we have the largest EQ compared to other animals. Ours is 7.5, meaning that we have a brain that’s 7.5 times larger than a mammal for our size but only 3.4 times as larger than expected for an anthropoid primate of its body mass (Azevedo et al, 2009). However, in stark contrast to the view of the people who view EQ as the reason why we are cognitively superior to other animals, what separates us in terms of cognitive ability is the difference in cortical neurons compared to other primates.

We humans have the most cortical neurons in our cerebral and prefrontal cortexes, relatively high neuron packing density (NPD), and much more cortical neurons of mammals of the same brain size (Roth and Dicke, 2012). Differences in intelligence across primate taxa best correlate with differences in number of cortical neurons, information processing speed, and synapses. Though, the human brain stands out having a “large cortical volume with a relatively NPD, high conduction velocity and high cortical parcellation.” This is why we are much more intelligent than other primates, due to the amount of cortical neurons we have as well as higher neuron packing density (keep this in mind for later). Encephalization quotient doesn’t explain intelligence differences within species, hence there being a problem with the use of encephalization to as the reason for human cognitive superiority, our Human Advantage, if you will.

Harry Jerison, the originator of the encephalization quotient, came to the conclusion that “human evolution … had been all about an advancement of encephalization quotients culminating in man.” (Herculano-Houzel, 2016: 15) What a conclusion. Just because EQ increased throughout hominin evolution, that means that it was all an advancement of EQs culminating to man. That’s circular logic.

Moreover, the “circular assumption” that higher EQ mean superior cognitive abilities in humans wasn’t founded on “tried-and-true correlations with actual measures of cognitive capacity.” (Herculano-Houzel, 2016: 15)

In second place on the EQ chart is the capuchin monkey coming in with an EQ of 2, which is more than double that of great apes who fall way below 1. That would imply that capuchin monkeys are more intelligent than great apes and outsmart great apes, right? Wrong. Great apes are. Total brain size predicts cognitive abilities in non-human primates better than EQ (Deaner et al, 2007).

Great apes significantly outperform other lineages. (Deaner, Schaik, and Johnson, 2006) Yet they have smaller EQs compared to other less intelligent primates. This is one of the largest problems with the EQ: total brain size is a better predictor of cognitive ability in non-human primates (Herculano-Houzel, 2011). She proposes that the absolute number of neurons, irrespective of brain size or body weight, is a better predictor of cognitive ability than is EQ.

Another problem with the EQ is that it assumes that all brains are made the same, and they aren’t. They scale differently between species. That’s one pretty huge flaw. Scaling is not the same across species, only within certain species. This one fatal flaw in EQ comparing different species of humans is why there is a problem with EQ in assessing cognitive abilities and why total brain size predicts cognitive abilities in non-human primates better than EQ.

Absolute brain size is a much better indicator of intelligence than the encephalization quotient.

So what exactly explains human cognitive superiority over other animals if the most often-used metric—the EQ—is flawed? An enlarged frontal cortex? No, the prefrontal areas in a human brain occupy 29 percent of the mass of the cerebral cortex. Moreover, the prefrontal cortex of humans, bonobos, chimpanzees, gorillas, and orangutans occupies the same 35-37 percent of all cortical volume (Semendeferei et al, 2002). (See also Herculano-Houzel, 2016: 119 and Gorillas Agree: Human Frontal Cortex is Nothing Special). Just because our frontal cortexes are all the same size, doesn’t mean that we don’t have a higher neuron packing density (NPD) than other primates. However, the human brain has the amount of neurons expected for its grey matter volume and total number of neurons remaining in the cerebral cortex; it has the white matter volume expected for amount of neurons; and the white matter volume and number of neurons expected for the number and volume of neurons in the “nonprefrontal subcortical white matter” (Herculano-Houzel, Watson, and Paxinos, 2013). The human prefrontal cortex is no larger than it ‘should’ be.

However, there seems to be a problem with Herculano-Houzel’s (2011) theory that absolute number of neurons predicts cognitive superiority (Mortenson et al, 2014). The long-finned pilot whale has 37,200,000 neurons in its cerebral cortex, more than double that of humans (16 billion). Does this call into question Herculano-Houzel’s (2011) theory on absolute number of neurons being the best case of human cognitive superiority over other animals?

In short, no. Neuron density is higher in humans than in the pilot whale. We have more neurons packed into our cerebral cortex. Their higher cell count is due only to their larger brains. And where it matters: pilot whales have a higher than expected amount of neocortical neurons relative to body weight, although not higher than humans. Herculano-Houzel’s (2011) theory is still in play here. They have big brains and in turn large amounts of glial cells to counter heat loss. So even then, this doesn’t counter Herculano-Houzel’s theory that the absolute amount of neurons dictates overall cognitive superiority.

Moreover, there is the same amount of cortical neurons in mice brains and human brains, with both mice and humans housing 8 percent of their total neurons in the prefrontal cortex. So what accounts for human cognitive superiority in humans compared to other primates? Most likely, the connectivity of the brain.

The connectivity in the brain of humans is not different from other species. The density of gray matter within species is fairly constant within mammalian species (Herculano-Houzel, 2016: 122). If true, then human prefrontal cortex, being nowhere near the largest, wouldn’t have the most synapses in our prefrontal cortex or anywhere else in the brain, and thus these wouldn’t be the largest. So, what does explain the cognitive superiority of humans over other animals in the animal kingdom?

All though all mammals use 8 percent of their total neurons in their prefrontal cortex, there is a differing distribution due to the amount of total neurons in each brain (remember, all brains aren’t made the same. It doesn’t hold for humans, and it especially doesn’t hold across phyla). We have 1.3 billion cortical neurons in our prefrontal cortex, baboons have 230 million, the macaque has 137 million and the marmoset has 20 million (Herculano-Houzel, 2016: 122). Prefrontal neurons are able to add complexity and flexibility, among other associative functions, to behavior while making planning for the future possible. All of these capabilities would increase with the more neurons a prefrontal cortex has (remember back to my article that the seat of intelligence (g) is the prefrontal cortex). So this seems to confirm the past studies showing the seat of intelligence to be the frontal cortex, due to the large amount of cortical neurons it has.

Herculano-Houzel writes the best definition of intelligence she’s ever heard, from MIT physicist Alex Wissner-Gross, which I believe is a great definition of intelligence:

The ability to plan for the future, a significant function of prefrontal regions of the cortex, may be key indeed. According to the best definition I have come across so far, put forward by MIT physicist Alex Wissner-Gross, intelligence is the ability to make decisions that maximize future freedom of action—that is, decisions that keep most doors open for the future. (Herculano-Houzel, 2016: 122-123)

All of the above are the direct result of more neurons in our frontal cortexes compared to other primates, which is why she finds it is the best definition of intelligence she’s ever heard.

Our ‘Human Advantage’ over other species comes down to the number of cortical neurons we have in our prefrontal cortex compared to other primates as well as the most neurons along with the highest NPD in the animal kingdom—which will be matched by no animal. The encephalization quotient has a lot of problems, with overall brain weight being a much better predictor of intelligence (Herculano-Houzel, 2011). Human cognitive superiority comes down to the total amount of neurons in our frontal cortex (1.3 billion neurons—where we will not be beaten) and our cerebral cortexes (16 billion neurons [long-finned pilot whales beat us out by more than double the amount, but we have more neurons packed into our cerebral cortex signifying our higher cognitive abilities). Within primates, total brain size predicts cognitive abilities better than EQ (Deaner et al, 2007).

Human cognitive superiority, contrary to popular belief, is not due to the EQ. It’s due to our NPD and amount of neurons in our frontal and cerebral cortexes that no other animal has–and we will not find another animal like this. This only would have been possible with the advent of bipedalism, tool-making, fire, cooking and meat eating. That’s what drives the evolution of brain size—and our evolution as a whole. Energy. Energy to reproduce, which then produce mutations which eventually coalesce new species.

Is There Progress in Hominin Brain Evolution?

2700 words

Tl;dr: The ‘trend’ in the evolution of hominin brain size is only due to diet quality and abundance. If there is any scarcity of food or a decrease in nutritional quality, there will be a subsequent decrease in brain size, as seen with H. floresiensis. Brain size, contrary to popular belief, has been decreasing for the past 20,000 years and has accelerated in the past 10,000. This trend is noticed all over the world with multiple hypotheses put out to explain the phenomenon. Despite this, people still deny that a decrease is occurring. Is it? Yes, it is. It’s due to a decrease in diet quality along with higher population density. If the human diet were to decrease in quality and caloric amount, our brains—along with our bodies—would become smaller over time.

Is there progress in hominin brain evolution? Many people may say yes. Over the past 7 million years, the human brain has tripled in size with most of this change occurring within the past 2 million years. This perfectly coincides with the advent of bipedalism, tool-making, fire, cooking and meat eating. Knowing the causal mechanisms behind the increase in hominin (primate) brain size, is there ‘progress’ to brain size in hominin evolution?

Looking at the evolution of hominin brain size in the past 7 million years, one can rightfully make the case that there is an evolutionary trend with the brain size increase. I don’t deny there is an increase, but first, before one says there is ‘progress’ to this phenomenon, you must look at it from both sides.

Montgomeroy et al (2010) reconstructed the ‘ups and downs’ of primate brain size evolution, and of course, decreases in hominin brain size can’t be talked about without bringing up H. floresiensis and his small brain and body mass, which they discuss as well. They come to the conclusion that “brain expansion began early in primate evolution”, also showing that there have been brain size increases in all clades of primates. Humans only show a bigger increase in absolute mass, with rate of proportional change in mass and relative brain size “having greater episodes of expansion elsewhere on the primate phylogeny”. Decreases in brain size also occurred in all of the major primate clades studied, they conclude that “while selection has acted to enlarge primate brains, in some lineages this trend has been reversed.” The selection can only occur in the presence of adequate kcal, keeping everyone sated and nourished enough to provide for the family, ensuring a woman gets adequate kcal and nutrients during pregnancy and finally ensuring that the baby gets the proper amount of energy for growth during infancy and childhood.

Montgomery et al write:

The branch with the highest rate of change in absolute brain mass is the terminal human branch (140,000 mg/million years). However for rate of proportional change in absolute brain mass the human branch comes only fourth, below the branches between the last common ancestor of Macaques and other Papionini, and the last common ancestor of baboons, mangabeys and mandrills (48 to 49), the ancestral primate and ancestral haplorhine (38 to 39) and the branch between the last common ancestor of Cebinae, Aotinae and Callitrichidae, and the ancestral Cebinae (58 to 60). The rate of change in relative brain mass along the human branch (0.068/million years) is also exceeded by the branch between the last common ancestor of Alouatta, Ateles and Lagothrix with the last common ancestor of Ateles and Lagothrix (branch 55 to 56; 0.73), the branch connecting the last common ancestor of Cebinae, Aotinae and Callitrichidae, and the ancestral Cebinae (branch 58 to 60; 0.074/million years) and the branch connecting the last common ancestor of the Papionini with the last common ancestor of Papio, Mandrillus and Cercocebus (branch 48 to 49; 0.084). We therefore conclude that only in terms of absolute mass and the rate of change in absolute mass has the increase in brain size been exceptional along the terminal branch leading to humans. Once scaling effects with body mass have been accounted for the rate of increase in relative brain mass remains high but is not exceptional.

“Remains high but is not exceptional”, ie, expected for a primate of our size (Azevedo et al, 2009). Of course, since evolution is not progressive, then finding any so-called ‘anomalies’ that ‘deviate’ from the ‘progress’ in brain size evolution makes sense. They conclude that floresiensis’ brain size and body mass decrease fell within the expected range of Argue et al’s (2009) proposed phylogenetic scenario. Though, only if he evolved from habilis or Dmansi hominins if the insular dwarfism hypothesis was taken into account (which is a viable explanation for the decrease).

The effects of food scarcity and its effect on hominin brain size is hardly ever spoken about. However, as I’ve been documenting here recently, caloric quality and amount dictate brain size. Montgomeory et al (2010) write:

Although many studies have investigated the possible selective advantages and disadvantages of increased brain size in primates [5, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21], few consider how frequently brain size has reduced. Periods of primate evolution which show decreases in brain size are of great interest as they may yield insights into the selective pressures and developmental constraints acting on brain size. Bauchot & Stephan [22] noted the evolution of reduced brain size in the dwarf Old World monkey Miopithecus talapoin and Martin [23] suggested relative brain size in great apes may have undergone a reduction based on the cranial capacity of the extinct hominoid Proconsul africanus. Taylor & van Schaik [24]reported a reduced cranial capacity in Pongo pygmaeus morio compared to other Orang-utan populations and hypothesise this reduction is selected for as a result of scarcity of food. Finally, Henneberg [25] has shown that during the late Pleistocene human absolute brain size has decreased by 10%, accompanied by a parallel decrease in body size.

[…]

These authors suggest this reduction is associated with an increase in periods of food scarcity resulting in selection to minimise brain tissue which is metabolically expensive [17]. Food scarcity is also believed to have played a role in the decrease in brain size in the island bovid Myotragus [12]. Taylor & van Schaik [24] therefore propose that H. floresiensis may have experienced similar selective pressures as Myotragus and Pongo p. morio.

Nice empirical vindication for me, if I don’t say so myself. This lends further credence to my scenario of an asteroid impact on earth halting food production leading to a scarcity in food. It’s hypothesized that floresiensis went from eating (if evolved from erectus) 1800 kcal per day and 2500 while nursing to 1200 per day and 1400 while nursing (Lieberman, 2013: 125). This, again, is proof that big brains need adequate energy and that cooking meat was what specifically drove this facet of our evolution.

Montgomeroy et al (2010) conclude:

Finally, our analyses add to the growing number of studies that conclude that the evolution of the human brain size has not been anomalous when compared to general primate brain evolution [59, 61, 91, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85, 86, 87, 88, 89, 90, 91, 92, 93, 94].

In other words, humans are not ‘special’ in terms of brain size. While there is a ‘trend’ in the increase in brain size, this ‘trend’ is only possible with the advent of fire, cooking, and meat eating. Without that causal mechanism, big brains would not be metabolically viable.

A big brain (large amounts of neurons) can only evolve with enough energy, mainly the advent of cooking meat (Herculano-Houzel, 2009). Primates have much higher neuronal densities than other mammals (Herculano-Houzel, Manger, and Kaas, 2014). Since the amount of energy the brain needs per day depends on how many total neurons it has (Azevedo and Herculano-Houzel, 2012), quality calories are needed to power such a metabolically expensive organ. Only with the advent of fire could we consume enough high-quality energy to evolve such big brains.

Mammalian brains that have 100 million neurons require .6 kcal, brains with 1 billion neurons use 6 kcal per day, and brains with 100 billion neurons use 600 kcal per day (humans with 86 billion neurons use 519 kcal, coming out to 6 kcal per neuron) regardless of the volumes of the brains (Herculano-Houzel, 2011). Knowing that the amount of neurons a brain has is directly related to how much energy it needs, it doesn’t seem so crazy now that, like with the example of floresiensis, a brain could decrease in size even when noticing this ‘upward trend’ in hominin brain size. This is simply because how big a brain is directly related to amount of energy available in an area as well as the most important variable: quality of the food.

If floresiensis is descended from habilis (and there is evidence that habilis was a meat eater, so along with a low amount of energy for floresiensis on Flora as well as there being no large predators on the island, a smaller size would have been advantageous to floresiensis), then this shows that what I’ve been saying for a few months is true: the diet quality as well as amount of energy dictates whether an organism evolves to be big or small. Energy is what ‘drives’ evolution in a sense and energy comes from kcal. The highest quality energy is from meat, and that fuels our ‘big brains’ with our high neuron count.

Imagine this scenario: an asteroid hits the earth and destroys the world power grid. All throughout the world, people cannot consume enough food. The sun is blocked by dust clouds for, say, 5000 years. The humans that survive this asteroid collision would evolve a smaller brain and body as well as better eyesight to see in an environment with low light, among other traits. Natural selection can only occur on the heritable variants already in the population, so whatever traits that would increase fitness in this scenario would multiply and flourish in the population, leading to a different, smaller-brained and smaller-bodied human due to the effects of the environment.

While on the subject of the decrease in human brain size, something that’s troubling to those who champion the ‘increase in hominin brain size’ as the ‘pinnacle of evolution’: our brains have been decreasing in size for at least the past 20,000 years according to John Hawks associate professor of anthropology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Keep in mind, this is someone that Pumpkin Person brings up saying that our brains have been increasing for the past 10,000 years. He has also said that the increase in better nutrition has allowed us to gain back the brain size of our hunter-gatherer ancestors (with no reference), which is not true. Because what John Hawks actually wrote on his blog about this says a different story:

The available skeletal samples show a reduction in endocranial volume or vault dimensions in Europe, southern Africa, China, and Australia during the Holocene. This reduction cannot be explained as an allometric consequence of reductions of body mass or stature in these populations. The large population numbers in these Holocene populations, particularly in post-agricultural Europe and China, rule out genetic drift as an explanation for smaller endocranial volume. This is likely to be true of African and Australian populations also, although the demographic information is less secure. Therefore, smaller endocranial volume was correlated with higher fitness during the recent evolution of these populations. Several hypotheses may explain the reduction of brain size in Holocene populations, and further work will be necessary to uncover the developmental and functional consequences of smaller brains.

In fact, from the Discover article on decreasing brain size, John Hawks says:

Hawks spent last summer measuring skulls of Europeans dating from the Bronze Age, 4,000 years ago, to medieval times. Over that period the land became even more densely packed with people and, just as the Missouri team’s model predicts, the brain shrank more quickly than did overall body size, causing EQ values to fall. In short, Hawks documented the same trend as Geary and Bailey did in their older sample of fossils; in fact, the pattern he detected is even more pronounced. “Since the Bronze Age, the brain shrank a lot more than you would expect based on the decrease in body size,” Hawks reports. “For a brain as small as that found in the average European male today, the body would have to shrink to the size of a pygmy” to maintain proportional scaling.

This is in stark contrast to what PP claims he says about the evolution of human brain size over the past 10,000 years, especially Europeans who he claims Hawks has said there has been an increase in European brain size. An increase in brain size over the past 100 years doesn’t mean a trend is occurring upward, since all other data on human brain size says otherwise.

Our brains have begun to decrease in size, which is due to the effects of overnutrition and diseases of civilization brought on by processed foods and the agricultural revolution. Another proposed cause for this is that population density tracks with brain size, with brain size increasing with a smaller population and decreasing with a bigger population. In a way, this makes sense. A bigger brain should have more neurons than a smaller brain, which would aid in cognitive tasks and have that one hominin survive better giving it a better chance to pass on its genes, so if you think about it, when the population increases when social trust forms, you can piggyback off of others and they wouldn’t have to do things on their own. As population size increased from sparse to dense, brain size decreased with it.

On this notion of ‘progress’ in brain size, some people may assume that this puts us at the ‘pinnacle’ of evolution due to our superior cognitive ability (which is due to the remarkably large amount of neurons in our cerebral cortex [Hercualno-Houzel, 2016: 102]), Herculano-Houzel writes on page 91 of her book The Human Advantage: A New Understanding of How Our Brains Became Remarkable:

We have long deemed ourselves to be at the pinnacle of cognitive abilities among animals. But that is different than being at the pinnacle of evolution in a number of important ways. As Mark Twain pointed out in 1903, to presume that evolution has been a long path leading to humans as its crowning achievement is just as preposterous as presuming that the whole purpose of building the Eiffel Tower was to put the final coat of paint on its tip. Moreover, evolution is not synonmous with progress, but simply change over time. And humans aren’t even the youngest, most recently evolved species. For example, more than 500 new species of cichlid fish in Lake Victoria, the youngest of the great African Lakes, have appeared since it filled with water some 14,500 years ago.

Using PP’s logic, the cichlid fishes of Lake Victoria are ‘more highly evolved’ than we are since they’re a ‘newer species’. Using that line of logic makes no sense now, putting it in that way.

Looking at the ‘trend’ in human brain size over the past 7 million years, and its acceleration in the past 2 million, without thinking about what jumpstarted it (bipedalism, tools, fire, meat eating) is foolish. Moreover, any change to our environment that decreases our energy input would, over time, lead to a decrease in our overall brain size perhaps more rapidly, showing that this ‘trend’ in the increase in brain size is directly related to the quality and amount of food in the area. This is why floresiensis’ brain and body shrunk, and why certain primate lineages show increases in brain size: because they have a higher-quality diet. But it comes at a cost. Since primates largely eat a plant-based diet, they have to eat upwards of 10 hours a day to get enough energy to power either their brains or their bodies. If their bodies are large, their brains are small and vice versa. A plant-based diet cannot power a large brain with a high neuron count like we have, it’s only possible with meat eating (Azevedo and Herculano-Houzel, 2012). This is one reason why floresiensis’ brain shrunk along with not enough kcal to sustain their larger brain and body mass that their ancestor they evolved from previously had.

Our brains are not particularly special, and in a way, you can thank fire and cooking meat for everything that’s occurred since erectus first controlled fire. For without a quality diet in our evolution, this so-called ‘trend’ (which is based on the environment due to food quality and scarcity/abundance which fluctuate) would not have occurred. In sum, this ‘progress’ will halt and ‘reverse’ if the amount of energy consumed decreases or diet quality decreases.

What Caused Human Brain Size to Increase?

1900 words

People talk a lot about intelligence and brain size. Something that’s most always brought up is how the human brain increased in size the past 4 million years. According to PP, the trend for bigger brains in hominins is proof that evolution is “progressive”. However, people never talk about a major event in human history that caused our brains to suddenly increase: the advent of fire. When our ancestors mastered fire, it was then possible for the brain to get important nutrients that influenced growth. People say that “Intelligence is the precursor to tools”, but what if fire itself is the main cause for the increase in brain size in hominins the past 4 million or so years? If this is the case, then fire is, in effect, the ultimate cause of everything that occurred after its use.

The human brain consumes 20-25 percent of our daily caloric intake. How could such a metabolically expensive organ have evolved? The first hominin to master fire was H. erectus. There is evidence of this occurring 1-1.5 mya. Not coincidentally, brain size began to tick upward after the advent of fire by H. erectus. Erectus was now able to consume more kcal, which in turn led to a bigger brain and the beginnings of a decrease in body size. The mastery and use of fire drove our evolution as a species, keeping us warm and allowing us to cook our food, which made eating and digestion easier. Erectus’s ability to use fire allowed for the biggest, in my opinion, most important event in human history: cooking.

With control of fire, Erectus could now cook its foods. Along with pulverizing plants, it was possible for erectus to get better nutrition by ‘pre-digesting’ the food outside of the body so it’s easier to digest. The advent of cooking allowed for a bigger brain and with it, more neurons to power the brain and the body. However, looking at other primates you see that they either have brains that are bigger than their bodies, or bodies that are bigger than their brains, why is this? One reason: there is a trade-off between brain size and body size and the type of diet the primate consumes. Thinking about this from an evolutionary perspective along with what differing primates eat and how they prepare (if they do) their food will show whether or not they have big brains or big bodies. How big an organism’s brain gets is directly correlated with the amount and quality of the energy consumed.

There is a metabolic limitation that results from the number of hours available to feed and the low caloric yield of raw foods which then impose a trade-off between the body size and number of neurons which explains why great apes have small brains in comparison to their bodies. Metabolically speaking, a body can only handle one or the other: a big brain or a big body. This metabolic disadvantage is why great apes did increase their brain size, because their raw-food diet is not enough, nutritionally speaking, to cause an increase in brain size (Azevedo and Herculano-Houzel, 2016). Can you imagine spending what amounts to one work day eating just to power the brain you currently have? I can’t.

Energy availability and quality dictates brain size. A brain can only reach maximum size if adequate kcal and nutrients are available for it.

Total brain metabolism scales linearly with the number of neurons (Herculano-Houzel, 2011). The absolute number of neurons, not brain size, dictates a “metabolic constraint on human evolution”, since people with more neurons need to sustain them, which calls for eating more kcal. Mammals with more neurons need to eat more kcal per day just to power those brains. For instance, the human brain needs 519 kcal to run, which comes out to 6 kcal per neuron. The brain is hugely metabolically expensive, and only the highest quality nutrients can sustain such an organ. The advent of fire and along with it cooking is one of, if not the most important reason why our brains are large (compared to our bodies) and why we have so many neurons compared to other species. It allowed us to power the neurons we have, 86 billion in all (with 16 billion in the cerebral cortex which is why we are more intelligent than other animals, number of neurons, of course being lower for our ancestors) which power human thought.

The Expensive Tissue Hypothesis (ETA) explains the metabolic trade-off between brain and gut, showing that the stomach is dependent on body size as well as the quality of the diet (Aiello, 1996). As noted above, there is good evidence that erectus began cooking, which coincides with the increase in brain size. As Man began to consume meat around 1.5 million years ago, this allowed for the gut to get smaller in response. If you think about it, it makes sense. A large stomach would be needed if you’re eating a plant-based diet, but as a species begins to eat meat, they don’t need to eat as much to get the adequate amount of kcal to fuel bodily functions. This lead to the stomach getting smaller, and along with it so did our jaws.

So brain tissue is metabolically expensive but there is no significant correlation between brain size and BMR in humans or any other encephalized mammal, the metabolic requirements of relatively large brains are offset by a corresponding gut reduction (Aiello and Wheeler, 1995). This is the cause for the low, insignificant correlation between BMR and our (relatively large brains, which correlates to the amount of neurons we have since our brains are just linearly scaled-up primate brains).

Evidence for the ETA can be seen in nature as well. Tsuboi et al (2015) tested the hypothesis in the cichlid fished of Lake Victoria. After they controlled for the effect of shared ancestry and other ecological variables, they noted that brain size was inversely correlated with gut size. Perhaps more interestingly, they also noticed that when the fish’s’ brain size increased, increased investment and paternal care occurred. Moreover, more evidence for the ETA was found by Liao et al (2015) who found a negative correlation between brain mass and the length of the digestive tract within 30 species of Anurans. They also found, just like Tsuboi et al (2015), that brain size increase accompanied an increase in female reproductive investment into egg size.

Moreover, another cause for the increase in brain size is our jaw size decreasing. This mutation occurred around 2.4 million years ago, right around the time frame that erectus discovered fire and began cooking. This is also consistent with, of course, the rapid increase in brain size which was occurring around that time. The room has to come from somewhere, and with the advent of cooking and meat eating, the jaw was, therefore, able to get smaller along with the stomach which increased brain size due to the trade-off between gut size and brain size. Morphological changes occurred exactly at the same time changes in brain size occurred which coincides with the advent of fire, cooking, and meat eating. Coincidence? I think the evidence strongly points that this is the case, the rapid increase in brain size was driven by fire, cooking, and meat eating.

The rise of bipedalism also coincided with the brain size increase and nutritional changes. Bipedalism freed the hands so tools could be made and used which eventually led to the control of fire. Lending more credence to the hypothesis of bipedalism/tools/brain size is the fact that there is evidence that the first signs of bipedalism occurred in Lucy, our Australopithecine ancestor who had pelvic architecture that showed she was clearly on the way to bipedalism. There is more evidence for bipedalism in fossilized footprints of australopithecines around 3 mya, coinciding with Lucy, tool use and eventually the advent and use of fire as a tool to cook and ward off predators. Ancient hominids could then better protect their kin, have higher quality food to eat and use the fire to scare off predators with.

The nutritional aspect of evolution and how it co-evolved with us driving our evolution in brain size which eventually led to us is extremely interesting. Without proper nutrients, it’s not metabolically viable to have such a large brain, as whatever kcal you do eat will need to go towards other bodily functions. Moreover, diet quality is highly correlated with brain size. Great apes can never get to the brain size that we humans have, and their diet is the main cause. The discovery and control of fire, the advent of cooking and then meat eating was what mainly drove the rapid increase of brain size starting 4 mya.

In a way, you can think of the passing down of the skill of fire-making to kin as one of the first acts of cultural transference to kin. It’s one of the first means of Lamarckian cultural transference in our history. Useful skills for survival will get passed down to the next generation, and fire is arguably the most useful skill we’ve ever come across since it’s had so many future implications for our evolution. The ability to create and control fire is one of the most important skills as it can ward off predators, cook meat, be used to keep warm, etc. When you think about how much time was freed up upon the advent of cooking, you can see the huge effect the control of fire first had for our species. Then think about how we could only control fire if our hands were freed. Then human evolution begins to make a lot more sense when put into this point of view.

When thinking about brain size evolution as well as the rapid expansion of brain size evolution, nutrition should be right up there with it. People may talk about things like the cold winter hypothesis and intelligence ad nauseam (which I don’t doubt plays a part, but I believe other factors are more important), but meat-eating along with a low waist-to-hip ratio, which bipedalism is needed for all are much more interesting when talking about the evolution of brain size than cold winters. All of this wouldn’t be possible without bipedalism, without it, we’d still be monkey-like eating plant-based diets. We’d have bigger bodies but smaller brains due to the metabolic cost of the plant-based diet since we wouldn’t have fire to cook and tools to use as we would have still been quadrupeds. The evolution of hominin intelligence is much more interesting from a musculoskeletal, physiological and nutritional point of view than any simplistic cold winter theory.

What caused human brain size to increase is simple: bipedalism, tools, fire, cooking, meat eating which then led to big brains. The first sign of big brains were noticed right around the time erectus had control of fire. This is no coincidence.

Bipedalism, cooking, and food drove the evolution of the human brain. Climate only has an effect on it insofar as certain foods will be available at certain latitudes. These three events in human history were the most important for the evolution of our brains. When thinking about what was happening physiologically and nutritionally around that time, the rebuttal to the statement of “Intelligence requires tools” is tools require bipedalism and further tools require bigger brains as human brains may have evolved to increase expertise capacity and not IQ (more on that in the future), which coincides with the three events outlined here. Whatever the case may be, the evolution of human intelligence is extremely interesting and is most definitely multifaceted.

The Human Brain Is Not Particularly Special: A New Way of Looking At the Human Brain

2000 words

What if I told you that, neuronally speaking, the human brain was not particularly special? That, despite its size in comparison to our bodies, we are not particularly special in comparison to other primates or mammals. The encephalization quotient supposedly shows how “unique” and “special” humans are in terms of brain size compared to body size. We have a brain that’s seven times bigger than would be expected for our body size, and that’s what supposedly makes us unique compared to the rest of the animals kingdom.

Suzana Herculano-Houzel, the new Associate Professor of Psychology at Vanderbilt University (former Associate Professor at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro), is a neuroscientist who challenges these notions that humans are supposedly unique in our brain size when compared to other mammals and primates. She pioneered a technique of turning brains into soup with a machine called the isotropic fractionator, which turns it into a “soup of a known volume” that contain the free cell nuclei to be colored and counted under a microscope. Using this technique, Azevedo et al (2009) showed that “with regard to numbers of neuronal and nonneuronal cells, the human brain is an isometrically scaled-up primate brain.” Every cell in the soup contains one nucleus, so counting is easy. Using this technique, they discovered that using the brain scaling of rats, a brain of 100 billion neurons would weigh 45 kg and body mass would be 109 tons. While using the primate scaling, a brain of 100 billion neurons would weigh 1.45 kg and belong to a body weighing 74 kg, suspiciously what humans are…. The human brain is constructed with the same rules as other primate’s brains. We are no different.

This is in direct opposition to brain size fetishists, who champion the fact that the human brain is some so-called ‘pinnacle of evolution’, as if all of the events that preceded us was setting the stage for our eventual arrival.

Of course, speaking in terms of body size, humans have the largest brains. However, the amount of neurons a brain has seems to be correlated to how cognitively complex the organism is. Humans have the most neurons for their brain size, however, that is one of the only things that sets us apart from other mammals/primates.

Azevedo et al (2009) write:

Our notion that the human brain is a linearly scaled-up primate brain in its cellular composition is in clear opposition to the traditional view that the human brain is 7.0 times larger than expected for a mammal and 3.4 times larger than expected for an anthropoid primate of its body mass (Marino, 1998). However, such large encephalization is found only when body-brain allometric rules that apply to nonprimates are used, as stated above, or when great apes are included in the calculation of expected brain size for a primate of a given body size.

Humans aren’t special in terms of neuronal and nonneuronal cells, our brains are just scaled-up versions of primate brains. There is nothing ‘weird’ or ‘unique’ about our brains; our brains follow the same ‘laws’ as other primates. Great apes such as the orangutans and gorillas are the ones who have brains that are smaller than their bodies. Their bodies are much larger than expected for primates of their brain size. That is where the outlier exists; not us.

The reason for our higher cognition is the 16 or so billion neurons in our cerebral cortex. For instance, the astounding human brain size in relation to body size is often touted, however, elephant’s brains are bigger, and they also have more neurons than we do. What sets us apart from elephants is that our cerebral cortex has about three times the amount of neurons compared to the elephant whose cerebral cortex is two times larger. The density of the neurons in our cerebral cortex seems to be the cause of our unique intelligence in the animal kingdom. Herculano-Houzel writes in her book The Human Advantage: A New Understanding of How Our Brains Became Remarkable (2016: 102):

The superior cognitive abilities of the human brain over the elephant brain can simply—and only—be attributed to the remarkably large number of neurons in its cerebral cortex.

Moreover, the absolute expansion of the cerebral cortex and its relative increase over the rest of the brain have been particularly fast in primate evolution (Herculano-Houzel, 2016: 110). I will return to the cause for this later.

She also noticed that in all of the papers that she read about the brain that the constant number quoted for the amount of neurons in the human brain was 100 billion. She continuously searched for the original citation and couldn’t find it. It wasn’t until she used her isotropic fractionator to get the true amount of neurons in the human brain—86 billion, which coincided with another stereological estimate.