Home » Posts tagged 'Lead'

Tag Archives: Lead

Nutrition and Antisocial Behavior

2150 words

What is the relationship between nutrition and antisocial behavior? Does not consuming adequate amounts of vitamins and minerals lead to an increased risk for antisocial behavior? If it does, then lower class people will have commit crimes at a higher rate, and part of the problem may indeed be dietary. Though, what kind of data is there that lends credence to the idea? It is well-known that malnutrition leads to antisocial behavior, but what kind of effect does it have on the populace as a whole?

About 85 percent of Americans lack essential vitamins and minerals. Though, when most people think of the word ‘malnutrition’ and the imagery it brings along with it, they assume that someone in a third-world country is being talked about, say a rail-thin kid somewhere in Africa who is extremely malnourished due to lack of kcal and vitamins and minerals. However, just because one lives in a first-world country and has access to kcal to where they’re “not hungry” doesn’t mean that vitamin and mineral deficiencies do not exist in these countries. This is known as “hidden hunger” when people can get enough kcal for their daily energy needs but what they are eating is lower-quality food, and thus, they become vitamin and nutrient deficient. What kind of effects does this have?

Infants are most at risk, more than half of American babies are at-risk for malnutrition; malnutrition in the postnatal years can lead to antisocial behavior and a lower ‘IQ’ (Galler and Ramsey, 1989; Liu et al, 2003; Galler et al, 2011, 2012a, 2012b; Gesch, 2013; Kuratko et al, 2013; Raine et al, 2015; Thompson et al, 2017). Clearly, not getting pertinent vitamins and minerals at critical times of development for infants leads to antisocial behavior in the future. These cases, though, can be prevented with a good diet. But the preventative measures that can prevent some of this behavior has been demonized for the past 50 or so years.

Poor nutrition leads to the development of childhood behavior problems. As seen in rat studies, for example, lack of dietary protein leads to aggressive behavior while rats who are protein-deficient in the womb show altered locomotor activity. The same is also seen with vitamins and minerals; monkeys and rats who were fed a diet low in tryptophan were reported to be more aggressive whereas those that were fed high amounts of tryptophan were calmer. Since tryptophan is one of the building blocks of serotonin and serotonin regulates mood, we can logically state that diets low in tryptophan may lead to higher levels of aggressive behavior. The role of omega 3 fatty acids are mixed, with omega 3 supplementation showing a difference for girls, but not boys (see Itomura et al, 2005). So, animal and human correlational studies and human intervention studies lend credence to the hypothesis that malnutrition in the womb and after birth leads to antisocial behavior (Liu and Raine, 2004).

We also have data from one randomized, placebo-controlled trial showing the effect of diet and nutrition on antisocial behavior (Gesch et al, 2002). They state that since there is evidence that offenders’ diets are lacking in pertinent vitamins and minerals, they should test whether or not the introduction of physiologically adequate vitamins, minerals and essential fatty acids (EFAs) would have an effect on the behavior of the inmates. They undertook an experimental, double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized trial on 231 adult prisoners and then compared their write-ups before and after nutritional intervention. The vitamin/mineral supplement contained 44 mg of DHA (omega 3 fatty acid docosahexaenoic acid; plays a key role in enhancing brain structure and function, stimulating neurite outgrowth), 80 mg of EPA (eicosapentaenoic acid; n3), and 1.26 g of ALA (alpha-linolenic acid), 1260mg of LA (linolic acid), and 160mg of GLA (gamma-Linolenic acid, n6) and a vegetable oil placebo. (Also see Hibbeln and Gow, 2015 for more information on n3 and nutrient deficits in childhood behavior disorders and neurodevelopment.)

Raine (2014: 218-219) writes:

We can also link micronutrients to specific brain structures involved in violence. The amygdala and hippocampus, which are impaired in offenders, are packed with zinc-containing neurons. Zinc deficiency in humans during pregnancy can in turn impair DNA, RNA, and protein synthesis during brain development—the building blocks of brain chemistry—and may result in very early brain abnormalities. Zinc also plays a role in building up fatty acids, which, as we have seen, are crucial for brain structure and function.

Gesch et al (2002) found pretty interesting results: those who were given the capsules with vitamins, minerals, and EFAs had 26.3 percent fewer offenses than those who got the placebo. Further, when compared with the baseline, when taking the supplement for two weeks, there was an average 35.1 percent reduction in offenses compared to the placebo group who showed little change. Gesch et al (2002) conclude:

Antisocial behaviour in prisons, including violence, are reduced by prisons, are reduced by vitamins, minerals and essential fatty acids with similar implications for those eating poor diets in the community.

Of course one could argue that these results would not transfer over to the general population, but to a critique like this, the observed effect of behavior is physiological; so by supplementing the prisoners’ diets giving them pertinent vitamins, minerals and EFAs, violence and antisocial behavior decreased, which shows some level of causation between nutrition/nutrient/fatty acid deprivation and antisocial behavior and violent activity.

Gesch et al (2002) found that some prisoners did not know how to construct a healthy diet nor did they know what vitamins were. So, naturally, since some prisoners didn’t know how to construct diets with an adequate amount of EFAs, vitamins and minerals, they were malnourished, though they consumed an adequate amount of calories. The intervention showed that EFA, vitamin and mineral deficiency has a causal effect on decreasing antisocial and violent behavior in those deficient. So giving them physiological doses lowered antisocial behavior, and since it was an RCT, social and ethnic factors on behavior were avoided.

Of course (and this shouldn’t need to be said), I am not making the claim that differences in nutrition explain all variance in antisocial and violent behavior. The fact of the matter is, this is causal evidence that lack of vitamin, mineral and EFA consumption has some causal effect on antisocial behavior and violent tendencies.

Schoenthaler et al (1996) also showed how correcting low values of vitamins and minerals in those deficient led to a reduction in violence among juvenile delinquents. Though it has a small n, the results are promising. (Also see Zaalberg et al, 2010.) These simple studies show how easy it is to lower antisocial and violent behavior: those deficient in nutrients just need to take some vitamins and eat higher-quality food and there should be a reduction in antisocial and violent behavior.

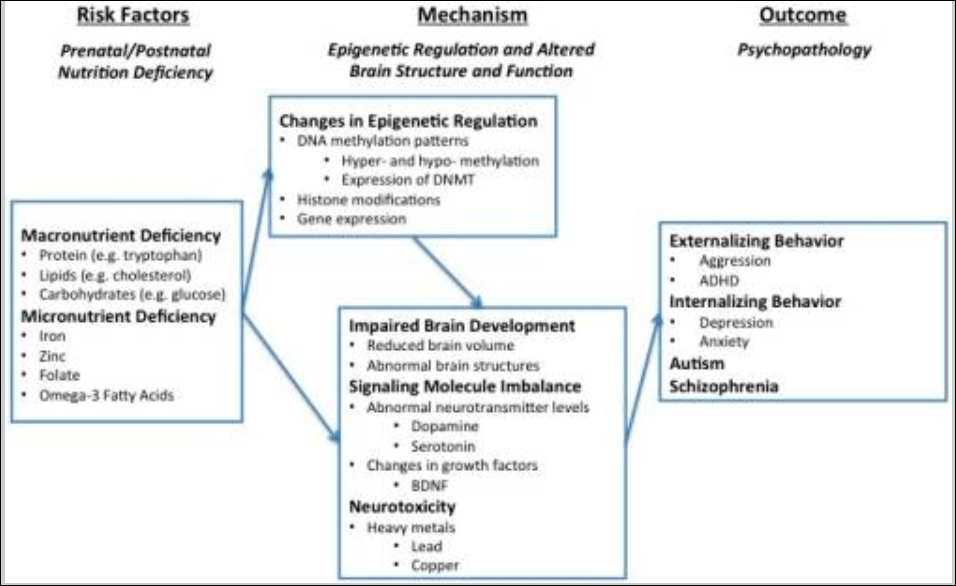

Liu, Zhao, and Reyes (2015) propose “a conceptual framework whereby epigenetic modifications (e.g., DNA methylation) mediate the link between micro- and macro-nutrient deficiency early in life and brain dysfunction (e.g., structural aberration, neurotransmitter perturbation), which has been linked to development of behavior problems later on in life.” Their model is as follows: macro- and micro-nutrient deficiencies are risk-factors for psychopathologies since they can lead to changes in the epigenetic regulation of the genome (along with other environmental variables such as lead consumption, which causes abnormal behavior and also epigenetic changes which can be passed through the generations; Senut et al, 2012; Sen et al, 2015) which then leads to impaired brain development, which then leads to externalizing behavior, internalizing behavior and autism and schizophrenia (two disorders which are also affected by the microbiome; Strati et al, 2017; Dickerson, 2017).

Clearly, since the food we eat gives us access to certain fatty acids that cannot be produced de novo in the brain or body, good nutrition is needed for a developing brain and if certain pertinent vitamins, minerals or fatty acids are missing, negative outcomes could occur for said individual in the future due to lack of brain development from being nutrient, vitamin, and mineral deficient in childhood. Further, interactions between nutrient deficiencies and exposure to toxic chemicals may be a cause of a large amount of antisocial behavior (Walsh et al, 1997; Hubbs-Tait et al, 2005; Firth et al, 2017).

Looking for a cause for this interaction between metal consumption and nutrient deficiencies, Liu, Zhao, and Reyes (2015) state that since protein and fatty acids are essential to brain growth, lack of consumption of pertinent micro- and macro-nutrients along with consumption of high amounts of protein both in and out of the womb contribute to lack of brain growth and, at adulthood, explains part of the difference in antisocial behavior. What you can further see from the above studies is that metals consumed by an individual can interact with the nutrient deficiencies in said individual and cause more deleterious outcomes, since, for example, lead is a nutrient antagonist—that is, it inhibits the physiologic actions of whatever bioavailable nutrients are available to the body for us.

Good nutrition is, of course, imperative since it gives our bodies what it needs to grow and develop as we grow in the womb, as adolescents and even into old age. So, therefore, developing people who are nutrient deficient will have worse behavioral outcomes. Further, lower class people are more likely to be nutrient deficient and consume lower quality diets than higher, more affluent classes, though it’s hard to discover which way the causation goes (Darmon and Drewnowski, 2008). Of course, the logical conclusion is that being deficient in vitamins, minerals and EFAs causes changes to the epigenome and retards brain development, therefore this has a partly causal effect on future antisocial, violent and criminal behavior. So, some of the crime difference between classes can be attributed to differences in nutrition/toxic metal exposure that induces epigenetic changes that change the structure of the brain and doesn’t allow full brain development due to lack of vitamins, minerals, and EFAs.

There seems to be a causal effect on criminal, violent and antisocial behavior regarding nutrient deficiencies in both juveniles and adults (which starts in the womb and continues into adolescence and adulthood). However, it has been shown in a few randomized controlled trials that nutritional interventions decrease some antisocial behavior, with the effect being strongest for those individuals who showed worse nutrient deficiencies.

If the relationship between nutrition/interaction between nutrient deficiencies and toxins can be replicated successfully then this leads us to one major question: Are we, as a society, in part, causing some of the differences in crime due to how our society is regarding nutrition and the types of food that are advertised to our youth? Are people’s diets which lead to nutrient deficiencies a driving factor in causing crime? The evidence so far on nutrition and its effects on the epigenome and its effects on the growth of the brain in the womb and adolescence requires us to take a serious look at this relationship. That lower class people are exposed to more neurotoxins such as lead (Bellinger, 2008) and are more likely to be nutrient deficient (Darmon and Drewnowski, 2008; Hackman, Farrah, and Meaney, 2011) then if they were educated on which foods to eat to avoid nutrient deficiencies along with avoiding neurotoxins such as lead (which exacerbate nutrient deficiencies and cause crime), then a reduction in crime should occur.

Nutrition is important for all living beings; and as can be seen, those who are deficient in certain nutrients and have less access to good, whole, nutritious food (who also have an increased risk for exposure to neurotoxins) can lead to negative outcomes. These things can be prevented, it seems, with a few vitamins/minerals/EFA consumption. The effects of sleep, poor diet (which also lead to metabolic syndromes) can also exacerbate this relationship, between individuals and ethnicities. The relationship between violence and antisocial behavior and nutrient deficiencies/the interaction with nutrient deficiencies and neurotoxins is a great avenue for future research to reduce violent crime in our society. Lower class people, of course, should be the targets of such interventions since there seems to be a causal effect—-however small or large—on behavior, both violent and nonviolent—and so nutrition interventions should close some of the crime gaps between classes.

Conclusion

The logic is very simple: nutrition affects mood (Rao et al, 2008; Jacka, 2017) which is, in part, driven by the microbiome’s intimate relationship with the brain (Clapp et al, 2017; Singh et al, 2017); nutrition also affects the epigenome and the growth and structure of the brain if vitamin and mineral needs are not met by the growing body. This then leads to differences in gene expression due to the foods consumed, the microbiome (which also influences the epigenome) further leads to differences in gene expression and behavior since the two are intimately linked as well. Thus, the aetiology of certain behaviors may come down to nutrient deficiencies and complex interactions between the environment, neurotoxins, nutrient deficiencies and genetic factors. Clearly, we can prevent this with preventative nutritional education, and since lower class people are more likely to suffer the most from these problems, the measures targeted to them, if followed through, will lower incidences of crime and antisocial/violent behavior.

Lead, Race, and Crime

2500 words

Lead has many known neurological effects on the brain (regarding the development of the brain and nervous system) that lead to many deleterious health outcomes and negative outcomes in general. Including (but not limited to) lower IQ, higher rates of crime, higher blood pressure and higher rates of kidney damage, which have permanent, persistent effects (Stewart et al, 2007). Chronic lead exposure, too, can “also lead to decreased fertility, cataracts, nerve disorders, muscle and joint pain, and memory or concentration problems” (Sanders et al, 2009). Lead exposure in vitro, in infancy, and in childhood can also lead to “neuronal death” (Lidsky and Schneider, 2003). While epigenetic inheritance also plays a part (Sen et al, 2015). How do blacks and whites differ in exposure to lead? How much is the difference between the two races in America, and how much would it contribute to crime? On the other hand, China has high rates of lead exposure, but lower rates of crime, so how does this relationship play out with the lead-crime relationship overall? Are the Chinese an outlier or is there something else going on?

The effects of lead on the brain are well known, and numerous amounts of effort have been put into lowering levels of lead in America (Gould, 2009). Higher exposure to lead is also found in poorer, lower class communities (Hood, 2005). So since higher levels of lead exposure are found more often in lower-class communities, then blacks should have higher blood-lead levels than whites. This is what we find.

Blacks had a 27 percent higher concentration of lead in their tibia, while having significantly higher levels of blood lead, “likely because of sustained higher ongoing lead exposure over the decades” (Theppeang et al, 2008). Other data—coming out of Detroit—shows the same relationships (Haar et al, 1979; Talbot, Murphy, and Kuller, 1982; Lead poisoning in children under 6 jumped 28% in Detroit in 2016; also see Maqsood, Stanbury, and Miller, 2017) while lead levels in the water contribute to high levels of blood-lead in Flint, Michigan (Hanna-Attisha et al, 2016; Laidlaw et al, 2016). Cassidy-Bushrow et al (2017) also show that “The disproportionate burden of lead exposure is vertically transmitted (i.e., mother-to-child) to African-American children before they are born and persists into early childhood.”

Children exposed to lead have lower brain volumes as children, specifically in the ventrolateral prefrontal cortex, which is the same region of the brain that is impaired in antisocial and psychotic persons (Cecil et al, 2008). The community that was tested was well within the ‘safe’ range set by the CDC (Raine, 2014: 224), though the CDC says that there is no safe level of lead exposure. There is a large body of studies which show that there is no safe level of lead exposure (Needleman and Landrigan, 2004; Canfield, Jusko, and Kordas, 2005; Barret, 2008; Rossi, 2008; Abelsohn and Sanborn, 2010; Betts, 2012; Flora, Gupta, and Tiwari, 2012; Gidlow, 2015; Lanphear, 2015; Wani, Ara, and Usmani, 2015; Council on Environmental Health, 2016; Hanna-Attisha et al, 2016; Vorvolakos, Aresniou, and Samakouri, 2016; Lanphear, 2017). So the data is clear that there is absolutely no safe level of lead exposure, and even small effects can lead to deleterious outcomes.

Further, one brain study of 532 men who worked in a lead plant showed that those who had higher levels of lead in their bones had smaller brains, even after controlling for confounds like age and education (Stewart et al, 2008). Raine (2014: 224) writes:

The fact that the frontal cortex was particularly reduced is very interesting, given that this brain region is involved in violence. This lead effect was equivalent to five years of premature aging of the brain.

So we have good data that the parts of the brain that relate to violent tendencies are reduced in people exposed to more lead had the same smaller parts of the brain, indicating a relationship. But what about antisocial disorders? Are people with higher levels of lead in their blood more likely to be antisocial?

Needleman et al (1996) show that boys who had higher levels of lead in their blood had higher teacher ratings of aggressive and delinquent behavior, along with higher self-reported ratings of aggressive behavior. Even high blood-lead levels later in life is related to crime. One study in Yugoslavia showed that blood lead levels at age three had a stronger relationship with destructive behavior than did prenatal blood lead levels (Wasserman et al, 2008); with this same relationship being seen in America with high blood lead levels correlating with antisocial and aggressive behavior at age 7 and not age 2 (Chen et al 2007).

Nevin (2007) showed a strong relationship between preschool lead exposure and subsequent increases in criminal cases in America, Canada, Britain, France, Australia, Finland, West Germany, and New Zealand. Reyes (2007) also shows that crime increased quicker in states that saw a subsequent large decrease in lead levels, while variations in lead levels within cities correlating with variations in crime rates (Mielke and Zahran, 2012). Nevin (2000) showed a strong relationship between environmental lead levels from 1941 to 1986 and corresponding changes to violent crime twenty-three years later in the United States. Raine (2014: 226) writes (emphasis mine):

So, young children who are most vulnerable to lead absorption go on twenty-three years later to perpetrate adult violence. As lead levels rose throughout the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s, so too did violence correspondingly rise in the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s. When lead levels fell in the late 1970s and early 1980s, so too did violence fall in the 1990s and the first decade of the twenty-first century. Changes in lead levels explained a full 91 percent of the variance in violent offending—an extremely strong relationship.

[…]

From international to national to state to city levels, the lead levels and violence curves match up almost exactly.

But does lead have a causal effect on crime? Due to the deleterious effects it has on the developing brain and nervous system, we should expect to find a relationship, and this relationship should become stronger with higher doses of lead. Fortunately, I am aware of one analysis, a sample that’s 90 percent black, which shows that with every 5 microgram increase in prenatal blood-lead levels, that there was a 40 percent higher risk of arrest (Wright et al, 2008). This makes sense with the deleterious developmental effects of lead; we are aware of how and why people with high levels of lead in their blood show similar brain scans/brain volume in certain parts of the brain in comparison to antisocial/violent people. So this is yet more suggestive evidence for a causal relationship.

Jennifer Doleac discusses three studies that show that blood-lead levels in America need to be addressed, since they are related strongly to negative health outcomes.Aizer and Curry (2017) show that “A one-unit increase in lead increased the probability of suspension from school by 6.4-9.3 percent and the probability of detention by 27-74 percent, though the latter applies only to boys.” They also show that children who live nearer to roads have higher blood-lead levels, since the soil near highways was contaminated decades ago with leaded gasoline. Fiegenbaum and Muller (2016) show that cities’ use of lead pipes increased murder rates between the years o921 and 1936. Finally, Billings and Schnepnel (2017: 4) show that their “results suggest that the effects of high levels of [lead] exposure on antisocial behavior can largely be reversed by intervention—children who test twice over the alert threshold exhibit similar outcomes as children with lower levels of [lead] exposure (BLL<5μg/dL).”

A relationship with lead exposure in vitro and arrests at adulthood. The sample was 90 percent black, with numerous controls. They found that prenatal and post-natal blood-lead exposure was associated with higher arrest rates, along with higher arrest rates for violent acts (Wright et al, 2008). To be specific, for every 5 microgram increase in prenatal blood-lead levels, there was a 40 percent greater risk for arrest. This is direct causal evidence for the lead-causes-crime hypothesis.

One study showed that in post-Katrina New Orleans, decreasing lead levels in the soil caused a subsequent decrease in blood lead levels in children (Mielke, Gonzales, and Powell, 2017). Sean Last argues that, while he believes that lead does contribute to crime, that the racial gaps have closed in the recent decades, therefore blood-lead levels cannot be a source of some of the variance in crime between blacks and whites, and even cites the CDC ‘lowering its “safe” values’ for lead, even though there is no such thing as a safe level of lead exposure (references cited above). White, Bonilha, and Ellis Jr., (2015) also show that minorities—blacks in particular—have higher rates of lead in their blood. Either way, Last seems to downplay large differences in lead exposure between whites and blacks at young ages, even though that’s when critical development of the mind/brain and other important functioning occurs. There is no safe level of lead exposure—pre- or post-natal—nor are there safe levels at adulthood. Even a small difference in blood lead levels would have some pretty large effects on criminal behavior.

Sean Last also writes that “Black children had a mean BLL which was 1 ug/dl higher than White children and that this BLL gap shrank to 0.9 ug/dl in samples taken between 2003 and 2006, and to 0.5 ug/dl in samples taken between 2007 and 2010.” Though, still, there are problems here too: “After adjustment, a 1 microgram per deciliter increase in average childhood blood lead level significantly predicts 0.06 (95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.01, 0.12) and 0.09 (95% CI = 0.03, 0.16) SD increases and a 0.37 (95% CI = 0.11, 0.64) point increase in adolescent impulsivity, anxiety or depression, and body mass index, respectively, following ordinary least squares regression. Results following matching and instrumental variable strategies are very similar” (Winter and Sampson, 2017).

Naysayers may point to China and how they have higher levels of blood-lead levels than America (two times higher), but lower rates of crime, some of the lowest in the world. The Hunan province in China has considerably lowered blood-lead levels in recent years, but they are still higher than developed countries (Qiu et al, 2015). One study even shows ridiculously high levels of lead in Chinese children “Results showed that mean blood lead level was 88.3 micro g/L for 3 – 5 year old children living in the cities in China and mean blood lead level of boys (91.1 micro g/L) was higher than that of girls (87.3 micro g/L). Twenty-nine point nine one per cent of the children’s blood lead level exceeded 100 micro g/L” (Qi et al, 2002), while Li et al (2014) found similar levels. Shanghai also has higher levels of blood lead than the rest of the developed world (Cao et al, 2014). Blood lead levels are also higher in Taizhou, China compared to other parts of the country—and the world (Gao et al, 2017). But blood lead levels are decreasing with time, but still higher than other developed countries (He, Wang, and Zhang, 2009).

Furthermore, Chinese women, compared to American women, had two times higher BLL (Wang et al, 2015). With transgenerational epigenetic inheritance playing a part in the inheritance of methylation DNA passed from mother to daughter then to grandchildren (Sen et al, 2015), this is a public health threat to Chinese women and their children. So just by going off of this data, the claim that China is a safe country should be called into question.

Reality seems to tell a different story. It seems that the true crime rate in China is covered up, especially the murder rate:

In Guangzhou, Dr Bakken’s research team found that 97.5 per cent of crime was not reported in the official statistics.

Of 2.5 million cases of crime, in 2015 the police commissioner reported 59,985 — exactly 15 less than his ‘target’ of 60,000, down from 90,000 at the start of his tenure in 2012.

The murder rate in China is around 10,000 per year according to official statistics, 25 per cent less than the rate in Australia per capita.

“I have the internal numbers from the beginning of the millennium, and in 2002 there were 52,500 murders in China,” he said.Instead of 25 per cent less murder than Australia, Dr Bakken said the real figure was closer to 400 per cent more.”

Guangzhou, for instance, doesn’t keep data for crime committed by migrants, who commit 80 percent of the crime in this province. Out of 2.5 million crimes committed in Guangzhou, only 5,985 crimes were reported in their official statistics, which was 15 crimes away from their target of 6000. Weird… Either way, China doesn’t have a similar murder rate to Switzerland:

The murder rate in China does not equal that of Switzerland, as the Global Times claimed in 2015. It’s higher than anywhere in Europe and similar to that of the US.

China also ranks highly on the corruption index, higher than the US, which is more evidence indicative of a covered up crime rate. So this is good evidence that, contrary to the claims of people who would attempt to downplay the lead-crime relationship, that these effects are real and that they do matter in regard to crime and murder.

So it’s clear that we can’t trust the official Chinese crime stats since there much of their crime is not reported. Why should we trust crime stats from a corrupt government? The evidence is clear that China has a higher crime—and murder rate—than is seen on the Chinese books.

Lastly, effects of epigenetics can and do have a lasting effect on even the grandchildren of mothers exposed to lead while pregnant (Senut et al, 2012; Sen et al, 2015). Sen et al (2015) showed lead exposure during pregnancy affected the DNA methylation status of the fetal germ cells, which then lead to altered DNA methylation on dried blood spots in the grandchildren of the mother exposed to lead while pregnant.—though it’s indirect evidence. If this is true and holds in larger samples, then this could be big for criminological theory and could be a cause for higher rates of black crime (note: I am not claiming that lead exposure could account for all, or even most of the racial crime disparity. It does account for some, as can be seen by the data compiled here).

In conclusion, the relationship between lead exposure and crime is robust and replicated across many countries and cultures. No safe level of blood lead exists, even so-called trace amounts can have horrible developmental and life outcomes, which include higher rates of criminal activity. There is a clear relationship between lead increases/decreases in populations—even within cities—that then predict crime rates. Some may point to the Chinese as evidence against a strong relationship, though there is strong evidence that the Chinese do not report anywhere near all of their crime data. Epigenetic inheritance, too, can play a role here mostly regarding blacks since they’re more likely to be exposed to high levels of lead in the womb, their infancy, and childhood. This could also exacerbate crime rates, too. The evidence is clear that lead exposure leads to increased criminal activity, and that there is a strong relationship between blood lead levels and crime.