Home » Philosophy (Page 4)

Category Archives: Philosophy

Blumenbachian Partitions and Mimimalist Races

2100 words

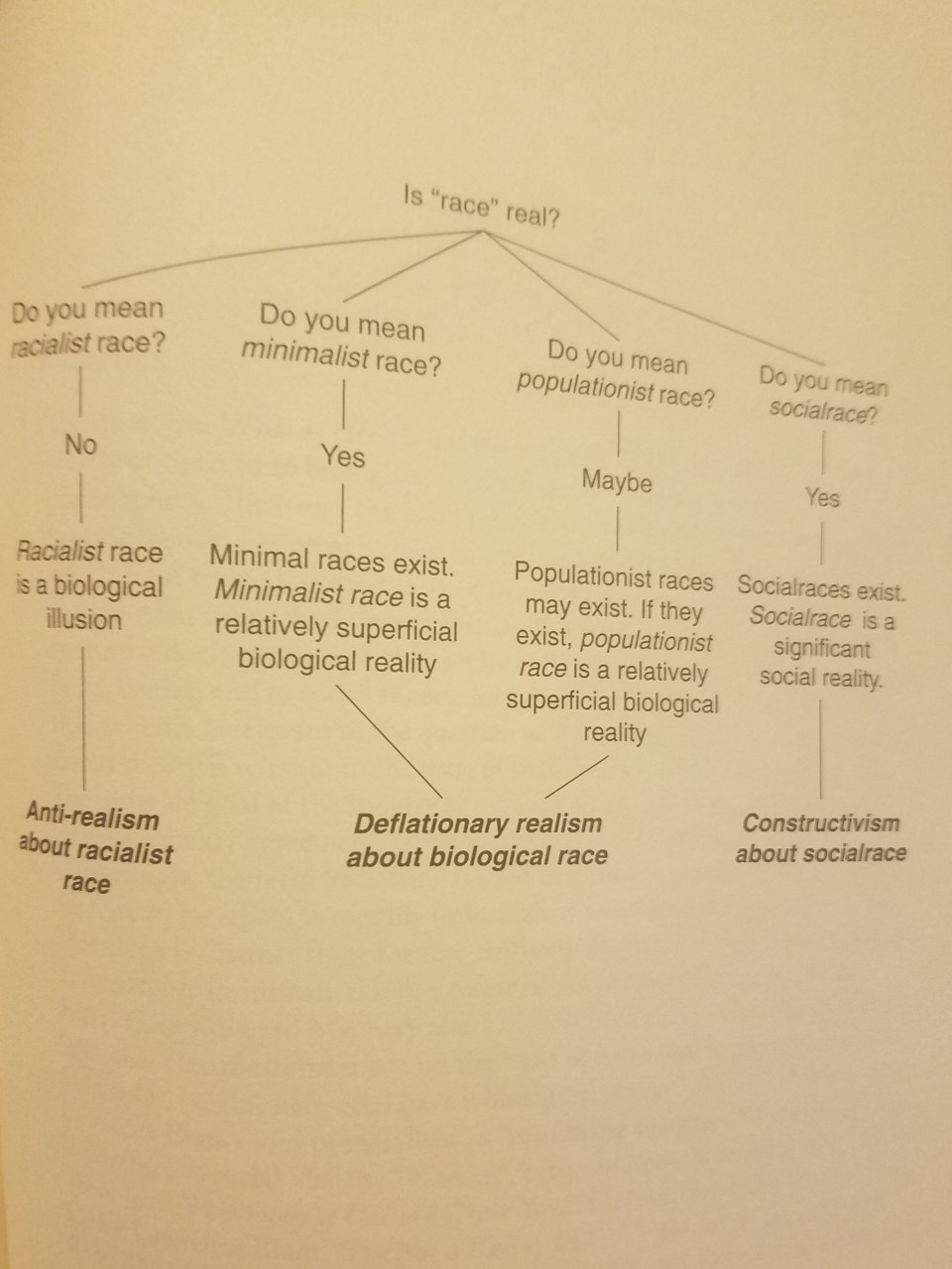

Race in the US is tricky. On one hand, we socially construct races. On the other, these socially constructed races have biological underpinnings. Racial constructivists, though, argue that even though biological races are false, races have come into existence—and continue to exist—due to human culture and human decisions (see the SEP). Sound arguments exist for the existence of biological races. Biological races exist, and they are real. One extremely strong view is from philosopher of science Quayshawn Spencer. In his paper A Radical Solution to the Race Problem, Spencer (2014) argues that biological races are real; that the term “race” directly refers; that race denotes proper names, not kinds; and these sets of human populations denoted by Americans can be denoted as a partition of human populations which Spencer (2014) calls “the Blumenbach partition”.

To begin, Spencer (2014) defines “referent”: “If, by using appropriate evidential methods (e.g., controlled experiments), one finds that a term t has a logically inconsistent set of identifying conditions but a robust extension, then it is appropriate to identify the meaning

of t as just its referent.” What he means is that the word “race” is just a referent, which means that the term “race” lies in what points out in the world. So, what “race” points out in the world becomes clear if we look at how Americans define “race”.

Spencer (2014) assumes that “race” in America is the “national meaning” of race. That is, the US meaning of race is just the referent to the Census definitions of race, since race-talk in America is tied to the US Census. But the US Census Bureau defers to the Office of Management and Budget (OMB). Therefore, since the US Census Bureau defers to the OMB on matters of race, and since Americans defer to the US Census Bureau, then Americans use the OMB definitions of race.

The OMB describes a “comprehensive set” of categories (according to the OMB) which lead Spencer (2014) to believe that the OMB statements on race are pinpointing Caucasians, Africans, Pacific Islanders, East Asians, and Amerindians. Spencer (2014: 1028-29) thusly claims that race in America “is a term that rigidly designates a particular set of “population groups.” Now, of course, the question is this: are these population groups socially constructed? Do they really exist? Are the populations identified arbitrary? Of course, the answer is that they identify a biologically real set of population groups.

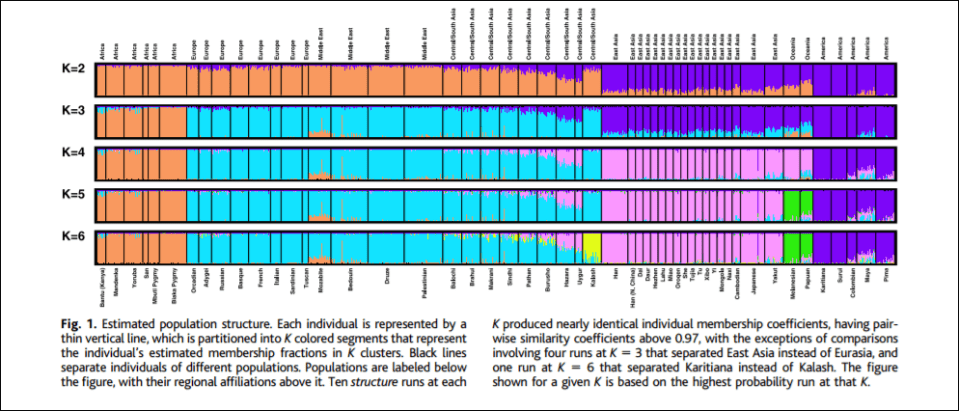

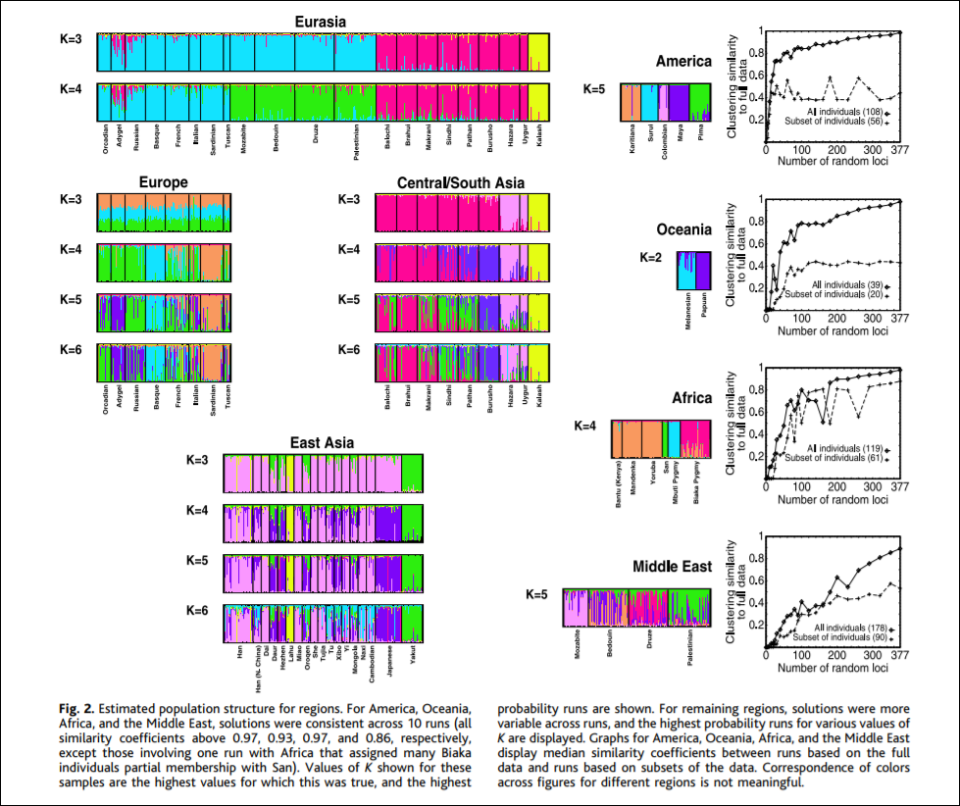

To prove the existence of his Blumenbachian populations, Spencer (2014) invokes populational genetic analyses. Population geneticists first must make the assumption at how many local populations exist in the target species. According to Spencer, “The current estimate for humans is 7,105 ethnic groups, half of which are in Africa and New Guinea.” After the assumptions are made, the next step is to sample the species’ estimated local populations. Then they must test noncoding DNA sequences. Finally, they must attempt to partition the sample so that each partition at each level is unique which then minimizes genetic differences in parts and maximizes genetic differences among parts. There are two ways of doing this: using structure and PCA. For the purposes of this argument, Spencer (2014) chooses structure, invoking a 5-population racial model, (see e.g., Rosenberg et al, 2002).

K = 5 corresponds to 5 populational clusters which denote Africans, Oceanians, East Asians, Amerindians, and Caucasians (Spencer, 2014; Hardimon, 2017b). K = 5 shows that the populations in question are genetically structured—that is, meaningfully demarcated on the basis of genetic markers and only genetic markers. Thus, that the populations in question are meaningfully demarcated on the basis of genetic markers, this is evidence that Hardimon’s (2017b) minimalist races are a biological reality. Furthermore, since Rosenberg et al (2002) used microsatellite markers in their analysis, this is a nonarbitrary way of constructing genetic clusters which then demarcate the continental-level minimalist races (Hardimon, 2017b: 90).

Thus, Spencer (2014) argues to call the partition identified in K = 5 “the Blumenbachian partition” in honor of Johann Blumenbach, anthropologist, physician, physiologist, and naturalist. (Though it should be noted that one of his races “Malays” was not a race, but Oceaninans are, so he “roughly discovered” the population partition.) So we can say that “the Blumenbach partition” is just the US meaning of “race”, the partitions identified by K = 5 (Rosenberg et al, 2002).

Furthermore, like Lewontin (1972), Rosenberg et al (2002) found that a majority of human genetic variation is between individuals, not races. That is, Rosenberg et al (2002) found that only 4.3 percent of human genetic variation was found to lie between the continental-level minimalist races. Thus, minimalist races are a biological kind, “if only a modest one” (Hardimon, 2017b: 91). Thus, Rosenberg et al (2002) support the contention that minimalist races exist and are a biological reality since a fraction of human population variation is due to differences among continental-level minimalist races (Africans, Caucasians, East Asians, Oceanians, and Amerindians). The old canard is true, there really is more genetic variation within races than between them, but, as can be seen, that does not rail against the reality of race, since that small amount of genetic variation shows that humanity is meaningfully clustered in a genetic sense.

Spencer (2014: 1032) then argues why Blumenbachian populations are “race” in the American sense:

It is not hard to generate accessible possible worlds that support the claim that US race terms are just aliases for Blumenbachian populations. For example, imagine a possible world τ where human history unfolded exactly how it did in our world except that every Caucasian in τ was killed by an infectious disease in the year 2013. Presumably, we have access to τ, since it violates no logical, metaphysical, or scientific principles. Then, given that we use ‘white’ in its national American meaning in our world, and given that we use ‘Caucasian’ in its Blumenbachian meaning in our world, it is fair to say that both ‘Caucasian’ and ‘white’ are empty terms in τ in 2014—which makes perfect sense if ‘white’ is just an alias for Caucasians. It is counterfactual evidence like this that strongly suggests that the US meaning of ‘race’ is just the Blumenbach partition.

Contrary to critics, this partition is biologically real and demarcates the five genetically structured populations of the human race. Rosenberg et al (2005) found that if sufficient data are used, “the geographic distribution of the sampled individuals has little effect on the analysis“, while their results verify that genetic clusters “arise from genuine features of the underlying pattern of human genetic variation, rather than as artifacts of uneven sampling along continuous gradients of allele frequencies.”

Some may claim that K = 5 is “arbitrary”, however, constructing genetic clusters using microsatellites is nonarbitrary (Hardimon, 2017b: 90):

Constructing genetic clusters using microsatellites constitutes a nonarbitrary way of demarcating the boundaries of continental-level minimalist races. And the fact that it is possible to construct genetic clusters corresponding to continental-level minimalist races in a nonarbitrary way is itself a reason for thinking that minimalist race is biologically real 62.

It should also be noted that Hardimon writes in note 62 (2017b: 197):

Just to be perfectly clear, I don’t think that the results of the 2002 Rosenberg article bear on the question: Do minimalist races exist? That’s a question that has to be answered separately. In my view, the fundamental question in the philosophy of race on which the results of this study bear is whether minimalist race is biologically real. My contention is that they indicate that minimalist race (or more precisely, continental-level minimalist race) is biologically real if sub-Saharan Africans, Caucasians, East Asians, Amerindians, and Oceanians constitute minimalist races.

Sub-Saharan Africans, Caucasians, East Asians, Amerindians, and Oceanians constitute minimalist races, therefore race is a biological reality. We can pinpoint them on the basis of patterns of visible physical features; these visible physical features correspond to geographic ancestry; this satisfies the criteria for minimalist races; therefore race exists. Race exists as a biological kind.

Furthermore, if these five populations that Rosenberg et al (2002) identified (the Blumenbachian populations) are minimalist races, then minimalist race is “a minor principle of human genetic structure” (Hardimon, 2017b: 92). Since minimalist races constitute a dimension within the small amount of human genetic variation that is captured between the continental-level minimalist races (4.3 percent), then it is completely possible to talk meaningfully about the racial structure of human genetic variation which consists of the human genetic variation which corresponds to continental-level minimalist races.

Thus, the US meaning of race is just a referent; the US meaning of race refers to a particular set of human populations; races in the US are classically-defined races (Amerindian, Caucasian, African, East Asian, and Oceanians; the Blumenbach partition); and race is both a biological reality as well as socially constructed. These populations are biologically real; if these populations are biologically real, then it stands to reason that biological racial realism is true (Hardimon, 2012 2013, 2017a; 2017b; Spencer, 2014, 2015).

Human races exist, in a minimalist biological sense, and there are 5 human races. Defenders of Rushton’s work—who believed there are only 3 primary races: Caucasoids, Mongoloids, and Negroids (while Amerindians and others were thrown into the “Mongoloid race” and Pacific Islanders being grouped with the “Negroid race” (Rushton, 1988, 1997; see also Liberman, 2001 for a critique of Rushton’s tri-racial views)—are forced into a tri-racial theory, since he used this tri-racial theory as the basis for his, now defunct, r/K selection theory. The tri-racial theory, that there are three primary races of man—Caucasoid, Mongoloid, and Negroid—has fallen out of favor with anthropologists for decades. But what we can see from new findings in population genetics since the sequencing of the human genome, however, is that human populations cluster into five populations and these five populations are races, therefore biological racial realism is true.

Biological racial realism (the fact that race exists as a biological reality) is true, however, just like with Hardimon’s minimalist races, they do not denote “superiority”, “inferiority” for one race over another. Most importantly, Blumenbachian populations do not denote those terms because the genetic evidence that is used to support the Blumenbachian partition use noncoding DNA. (It should also be noted that the terms “superior” and “inferior” are nonsensical, when used outside of their anatomic contexts. The head is the most superior part of the human body, the feet are the most inferior part of the human body. This is the only time these terms make sense, thus, using the terms outside of this context makes no sense.)

It is worth noting that, while Hardimon’s and Spencer’s views on race are similar, there are some differences between their views. Spencer sees “race” as a referent, while Hardimon argues that race has a set descriptive meaning on the basis of C (1)-(3); (C1) that, as a group, is distinguished from other groups of human beings by patterns of visible physical features, (C2) whose members are linked be a common ancestry peculiar to members of that group, and (C3) that originates from a distinctive geographic location” (Hardimon, 2017b: 31). Whether or not one prefers Blumenbachian partitions or minimalist races depends on whether or not one prefers race in a descriptive sense (i.e., Hardimon’s minimalist races) or if the term race in America is a referent to the US Census discourse, which means that “race” refers to the OMB definitions which then denote Blumenbachian partitions.

Hardimon also takes minimalist races to be a biological kind, while Spencer takes them to be a proper name for a set of population groups. Both of these differing viewpoints regarding race, while similar, are different in that one is describing a kind, while the other describes a proper name for a population group; these two views regarding population genetics from these two philosophers are similar, they are talking about the same things and hold the same deflationary views regarding race. They are talking about how race is seen in everyday life and where people get their definitions of “race” from and how they then integrate it into their everyday lives.

“Race” in America is a proper name for a set of human population groups, the five population groups identified by K = 5. Americans defer to the US Census Bureau on race, who defers to the Office of Management and Budget to define race. They hold that races are a “set”, and these “sets” are Oceanians, Caucasians, East Asians, Amerindians, and Africans. Race, thusly, refers to a set of population groups; “race” is not a “kind”, but a proper name for known populational groups. K = 5 then shows us that the demarcated clusters correspond to continental-level minimalist races, what is termed “the Blumenbach partition.” This partition is “race” in the US sense of the term, and it is a biological reality, therefore, like Hardimon’s minimalist races, the Blumenbach partition identifies what we in America know to be race. (It’s worth noting that, obviously, the Blumenbach partition/minimalist races are one in the same, Spencer is a deflationary realist regarding race, just like Hardimon.)

Defending Minimalist Races: A Response to Joshua Glasgow

2000 words

Michael Hardimon published Rethinking Race: The Case for Deflationary Realism last year (Hardimon, 2017). I was awaiting some critical assessment of the book, and it seems that at the end of March, some criticism finally came. The criticism came from another philosopher, Joshua Glasgow, in the journal Mind (Glasgow, 2018). The article is pretty much just arguing against his minimalist race concept and one thing he brings up in his book, the case of a twin earth and what we would call out-and-out clones of ourselves on this twin earth. Glasgow makes some good points, but I think he is largely misguided on Hardimon’s view of race.

Hardimon (2017) is the latest defense for the existence of race—all the while denying the existence of “racialist races”—that there are differences in mores, “intelligence” etc—and taking the racialist view and “stripping it down to its barebones” and shows that race exists, in a minimal way. This is what Hardimon calls “social constructivism” in the pernicious sense—racialist races, in Hardimon’s eyes, are socially constructed in a pernicious sense, arguing that racialist races do not represent any “facts of the matter” and “supports and legalizes domination” (pg 62). The minimalist concept, on the other hand, does not “support and legalize domination”, nor does it assume that there are differences in “intelligence”, mores and other mental characters; it’s only on the basis of superficial physical features. These superficial physical features are distributed across the globe geographically and these groups are real and exist who show these superficial physical features across the globe. Thus, race, in a minimal sense, exists. However, people like Glasgow have a few things to say about that.

Glasgow (2018) begins by praising Hardimon (2017) for “dispatching racialism” in his first chapter, also claiming that “academic writings have decisively shown why racialism is a bad theory” (pg 2). Hardimon argues that to believe in race, on not need believe what the racialist concept pushes; one must only acknowledge and accept that there are:

1) differences in visible physical features which correspond to geographic ancestry; 2) these differences in visible features which correspond to geographic ancestry are exhibited between real groups; 3) these real groups that exhibit these differences in physical features which correspond to geographic ancestry satisfy the conditions of minimalist race; C) therefore race exists.

This is a simple enough argument, but Glasgow disagrees. As a counter, Glasgow brings up the “twin earth” argument. Imagine a twin earth was created. On Twin Earth, everything is exactly the same; there are copies of you, me, copies of companies, animals, history mirrored down to exact minutiae, etc. The main contention here is that Hardimon claims that ancestry is important for our conception of race. But with the twin earth argument, since everything, down to everything, is the same, then the people who live on twin earth look just like us but! do not share ancestry with us, they look like us (share patterns of visible physical features), so what race would we call them? Glasgow thusly states that “sharing ancestry is not necessary for a group to count as a race” (pg 3). But, clearly, sharing ancestry is important for our conception of race. While the thought experiment is a good one it fails since ancestry is very clearly necessary for a group to count as a race, as Hardimon has argued.

Hardimon (2017: 52) addresses this, writing:

Racial Twin Americans might share our concept of race and deny that races have different geographical origins. This is because they might fail to understand that this is a component of their race concept. If, however, their belief that races do not have different geographical origins did not reflect a misunderstanding of their “race concept,” then their “race concept” would not be the same concept as the concept that is the ordinary race concept in our world. Their use of ‘race’ would pick out a different subject matter entirely from ours.

and on page 45 writes:

Glasgow envisages Racial Twin Earth in such a way that, from an empirical (that is, human) point of view, these groups would have distinctive ancestries, even if they did not have distinctive ancestries an sich. But if this is so, the groups [Racial Twin Earthings] do not provide a good example of races that lack distinctive ancestries and so do not constitute a clear counterexample to C(2) [that members of a race are “linked by a common ancestry peculiar to members of that group”].

C(2) (P2 in the simple argument for the existence of race) is fine, and the objections from Glasgow do not show that P(C)2 is false at all. The Racial Twin Earth argument is a good one, it is sound. However, as Hardimon had already noted in his book, Glasgow’s objection to C(2) does not rebut the fact that races share peculiar ancestry unique to them.

Next, Glasgow criticizes Hardimon’s viewpoints on “Hispanics” and Brazilians. These two groups, says Glasgow, shows that two siblings with the same ancestry, though they have different skin colors, would be different races in Brazil. He uses this example to state that “This suggests that race and ancestry can be disconnected” (pg 4). He criticizes Hardimon’s solution to the problem of race and Brazilians, stating that our term “race” and the term in Brazil do not track the same things. “This is jarring. All that anthropological and sociological work done to compare Brazil with the rest of the world (including the USA) would be premised on a translation error” (pg 4). Since Americans and Brazilians, in Glasgow’s eyes, can have a serious conversation about race, this suggests to Glasgow that “our concept of race must not require that races have distinct ancestral groups” (pg 5).

I did cover Brazilians and “Hispanics” as regards the minimalist race concept. Some argue that the “color system” in Brazil is actually a “racial system” (Guimaraes 2012: 1160). While they do denote race as ‘COR’ (Brazilian for ‘color), one can argue that the term used for ‘color’ is ‘race’ and that we would have no problem discussing ‘race’ with Brazilians, since Brazilians and Americans have similar views on what ‘race’ really is. Hardimon (2017: 49) writes:

On the other hand, it is not clear that the Brazilian concept of COR is altogether independent of the phenomenon we Americans designate using ‘race.’ The color that ‘COR’ picks out is racial skin color. The well-known, widespread preference for lighter (whiter) skin in Brazil is at least arguably a racial preference. It seems likely that white skin color is preferred because of its association with the white race. This provides a reason for thinking that the minimalist concept of race may be lurking in the background of Brazilian thinking about race.

Since ‘COR’ picks out racial skin color, it can be safely argued that Brazilians and Americans at least are generally speaking about the same things. Since the color system in Brazil pretty much mirrors what we know as racial systems, demarcating races on the basis of physical features, we are, it can be argued, talking about the same (or similar) things.

Further, the fact that “Latinos” do not fit into Hardimon’s minimalist race concepts is not a problem with Hardimon’s arguments about race, but is a problem with how “Latinos” see themselves and racialize themselves as a group. “Latinos” can count as a socialrace, but they do not—can not—count as a minimalist race (such as the Caucasian minimalist race; the African minimalist race; the Asian minimalist race etc), since they do not share visible physical patterns which correspond to differences in geographic ancestry. Since they do not exhibit characters that demarcate minimalist races, they are not minimalist races. Looking at Cubans compared to, say, Mexicans (on average) is enough to buttress this point.

Glasgow then argues that there are similar problems when you make the claim “that having a distinct geographical origin is required for a group to be a race” (pg 5). He says that we can create “Twin Trump” and “Twin Clinton” might be created from “whole cloth” on two different continents, but we would still call them both “white.” Glasgow then claims that “I worry that visible trait groups are not biological objects because the lines between them are biologically arbitrary” (pg 5). He argues that we need a “dividing line”, for example, to show that skin color is an arbitrary trait to divide races. But if we look at skin color as an adaptation to the climate of the people in question (Jones et al, 2018), then this trait is not “arbitrary”, and the trait is then linked to geographic ancestry.

Glasgow then goes down the old and tired route that “There is no biological reason to mark out one line as dividing the races rather than another, simply based on visible traits” (pg 5). He then goes on to discuss the fact that Hardimon invokes Rosenberg et al (2002) who show that our genes cluster in specific geographic ancestries and that this is biological evidence for the existence of race. Glasgow brings up two objections to the demarcation of races on both physical appearance and genetic analyses: picture the color spectrum, “Now thicken the orange part, and thin out the light red and yellow parts on either side of orange. You’ve just created an orange ‘cluster’” (pg 6), while asking the question:

Does the fact that there are more bits in the orange part mean that drawing a line somewhere to create the categories orange and yellow now marks a scientifically principled line, whereas it didn’t when all three zones on the spectrum were equally sized?

I admit this is a good question, and that this objection would indeed go with the visible trait of skin color in regard to race; but as I said above, since skin color can be conceptualized as a physical adaptation to climate, then that is a good proxy for geographic ancestry, whether or not there is a “smooth variation” of skin colors as you move away from the equator or not, it is evidence that “races” have biological differences and these differences start on the biggest organ in the human body. This is just the classic continuum fallacy in action: that X and Y are two different parts of an extreme; there is no definable point where X becomes Y, therefore there is no difference between X and Y.

As for Glasgow’s other objection, he writes (pg 6):

if we find a large number of individuals in the band below 62.3 inches, and another large grouping in the band above 68.7 inches, with a thinner population in between, does that mean that we have a biological reason for adopting the categories ‘short’ and ‘tall’?

It really depends on what the average height is in regard to “adopting the categories ‘short’ and ‘tall’” (pg 6). The first question was better than the second, alas, they do not do a good job of objecting to Hardimon’s race concept.

In sum, Glasgow’s (2018) review of Hardimon’s (2017) book Rethinking Race: The Case for Deflationary Realism is an alright review; though Glasgow leaves a lot to be desired and I do think that his critique could have been more strongly argued. Minimalist races do exist and are biologically real.

I am of the opinion that what matters regarding the existence of race is not biological science, i.e., testing to see which populations have which differing allele frequencies etc; what matters is the philosophical aspects to race. The debates in the philosophical literature regarding race are extremely interesting (which I will cover in the future), and are based on racial naturalism and racial eliminativism.

(Racial naturalism “signifies the old, biological conception of race“; racial eliminativism “recommends discarding the concept of race entirely“; racial constructivism “races have come into existence and continue to exist through “human culture and human decisions” (Mallon 2007, 94)“; thin constructivism “depicts race as a grouping of humans according to ancestry and genetically insignificant, “superficial properties that are prototypically linked with race,” such as skin tone, hair color and hair texture (Mallon 2006, 534); and racial skepticism “holds that because racial naturalism is false, races of any type do not exist“.) (Also note that Spencer (2018) critiques Hardimon’s viewpoints in his book as well, which will also be covered in the future, along with the back-and-forth debate in the philosophical literature between Quayshawn Spencer (e.g., 2015) and Adam Hochman (e.g., 2014).)

“Latinos”, Brazilians, Mixed-Race Individuals and Race Concepts

2050 words

How do “Latinos”, Brazilians, and mixed-race individuals fit into Hardimon’s (2017) differing race concepts (racialist, minimalist, populationist, and socialrace)? It’s easier explaining how “Latinos” fit into this, but mixed-race individuals are a bit trickier (for instance, the minimalist concept of race does not say anything about it and is therefore vague in that respect). This article will discuss these two populations and see where they fit into these categories.

Mixed-race individuals

Mixed-race individuals are tricky to place in these conceptions of race that Hardimon (2017) lays out and defends. For example, minimalist race itself is vague; it does not say which populations/individuals with populational characteristics would be placed, the argument just establishes the biological reality and significance of race. The concept of the “one drop rule” (was a legal) is a social standard in that anyone with “one drop” of “black blood” was deemed black (which, it seems, did well for so-called conceptions of “racial purity” since most white Americans have low amounts of black ancestry; Bryc et al, 2015).

The one drop rule was an attempt to limit racial miscegenation (racial mixing), and it seems to have, for the most part, worked since many white Americans have low to no African ancestry (since 95 percent of white Americans have no African ancestry; Bryc et al, 2015).

Though, as Hardimon (2017: 49) writes, the fact that individuals must have a race is a holdover from the racialist concept; minimalist race, as I’ve covered, is not defined by the features of an individual but is defined by the features of the group said individual belongs to. It is defined in terms of group—not individual—characteristics. So just because individual I doesn’t look like their R but instead looks like an R2, for example, doesn’t make individual I an R2; individual I is still an R even though they look like an R2 since the concept is based on shared group characteristics.

Hardimon doesn’t really discuss mixed-race individuals in his book; there’s only really one note on the subject (and it’s about social race, pg. 209, note 54):

People who are members of more than one socialrace in a socialrace regime that does not recognize mixed race as a racial position will be in the anomalous situation of not having an established socialrace position in society. Having such a position is one way of being a “normal” member of society organized around the institution of socialrace. Not to have such a position is to have no place in the social world along the dimension of socialrace. Hence, perhaps, the pathos of mixed-race individuals seeking social recognition for their distinctive mixed race identity.

Though, in certain (racialist/socialrace) societies, a mixed-race individual would become what the “lower” race is in that society. For instance, if an individual were half white and half black—like the former President of the United States Barack Obama—he would be designated as “black”, as we all know (since he’s the first black President of the United States). This is known as the concept of “hypodescent” and has its basis in Hardimon’s socialrace concept since racial status of the offspring is designated to the parent who has lower “standing” than the majority in said country. So, therefore, the concept of hypodescent is the concept of socialrace in action.

Mixed-race individuals are seen as members of their “lower-status parent group“, which shows how racial constructivism is alive today. One is designated the lower-status of their parent in a hierarchical manner—one way in which the socialrace concept borrows from the racialist race concept in that it is hierarchical.

The researchers found, for example, that one-quarter-Asian individuals are consistently considered more white than one-quarter-black individuals, despite the fact that African Americans and European Americans share a substantial degree of genetic heritage. One Drop Rule Persists—Harvard

Brazil

How does this work in Brazil? Surely this makes problems for racial concepts, right?

Brazilians don’t use the term “race” (raca), but the term “color” (cor). “The reason the word Color (capitalized to call attention to this particular meaning) is preferred to race in Brazil is probably because it captures the continuous aspects of phenotypes” (Parra et al, 2003). Clearly, the conception of “race” (raca) in Brazil comes down to what “color” (cor) one is; and so we should state that Brazilian society is stratified into “colors” and not true “races”. The 1872 Brazilian census created four “color” groups “white, caboclo, black and brown (branco, caboclo (mixed indigenous-European), negro and pardo). These groups were always defined by the same formula: Colour group = members of a pure race + phenotypes of this race in the process of reversion (Guimaraes 1999)” (Guimaraes, 2012: 1157).

Though, distinct from Hardimon (2017), Guimaraes (2012: 1160) argues that the Brazilian color system is, in fact, a racial system:

What makes colour in Brazil a racial term is precisely the fact that the physiognomic traits used by racialists to distinguish different human races became convoluted with the original European system of classification based on shades of skin colour.

Hardimon (2017: 49) writes:

On the other hand, it is not clear that the Brazilian concept of COR is altogether independent of the phenomenon we Americans designate using ‘race.’ The color that ‘COR’ picks out is racial skin color. The well-known, widespread preference for lighter (whiter) skin in Brazil is at least arguably a racial preference. It seems likely that white skin color is preferred because of its association with the white race. This provides a reason for thinking that the minimalist concept of race may be lurking in the background of Brazilian thinking about race.

Someone who is “white” (identifies as white) in Brazil will (most likely) not be white in America; this is due to their differing classification system based on color, which is loosely tied with the minimalist concept, but is distinct from it in that it’s just based largely on the color of one’s skin (one of many requisites for minimalist racehood).

The role of race and color in regard to Brazilian society is complex, biologically, sociologically, and psychologically; but it’s clear that some concept of what we could call a “classical” race concept—however crude—could be said to be in use in Brazil today.

Latinos/Hispanics

The US Census Bureau states that “People who identify their origin as Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish may be of any race.” This is true; just because one derives from a Latin American country does not mean that they are some kind of “Latino” or “Hispanic” race.

Take, as an example, the case of Alberto Fujimori. Alberto Fujimori is the son of Japanese immigrants to Peru, and he eventually ended up becoming the President of Peru. His parents emigrated to Peru and he was born in Lima. Now here’s where things get tricky: is he all of a sudden some new type of “race” called “Hispanic” or “Latino”, all because he was born across the ocean? Is Pope Francis all of a sudden not Italian by ancestry since he was born in Argentina? Are people who are born in Argentina, Chile, and Paraguay with direct ancestry to Germany and Italy all of a sudden no longer German or Italian but some new “Hispanic” or “Latino” race? No! Just because you’re born not in your ancestral home does not mean you “become” whatever society designates that part of the world (in this case “Latin America”). Their race does not change on the basis of where they are born; their individual ancestries can still be traced back to their countries of origin, therefore attempting to “racialize” the terms “Hispanic” or “Latino” do not make any sense.

“Hispanics” do not—and cannot—count as a minimalist race on the basis of one condition: they do not share a single pattern of visible physical features. No one pattern of hair, skin color, lip shape, eye shape etc. They do not share a single geographic origin; they have a mixture of Ancestry from Africa, Europe, and Asia. “Hispanics” can be seen, obviously, as a mixture of minimalist races. “Hispanics” are denied minimalist racehood since they do not exhibit characteristics of minimalist races, which is even echoed, as shown above, by the US Census Bureau.

Hardimon (2017: 39) writes:

To deny that Latinos constitute a race is not to deny that individual Latinos or Latinos as a group can be the targets of racism (for example, owing to skin color). Nor is it to deny that Latinos are often regarded as “racially other” (as differing in some essential humanly important way corresponding to skin color) by members of other racialized groups (for example, Anglos). … Nor is it to deny that they constitute a socialrace in my sense of the term. Still less does it imply that Latinos ought not to aspire to a degree of solidarity connoted by the Spanish word raza.

So “Latinos” can be designated as a socialrace (though socialraces do not always have a mirrored minimalist race), but not as a minimalist race since they do not fit the criteria for minimalist racehood. Many “Latinos” can be said to be mestizos, which are half European (normally of Spanish descent) and half Indian. Still, further, they can be castizos, about three-quarters European and one-quarter Indian. Then you have the “Latino” Carribean countries (Dominican Republic, Cuba, Puerto Rico) with differing amounts of admixture from all over, from different minimalist races. Though, in America, most Dominicans would be counted as “black” under the concept of “hypodescent”—the one drop rule. Many Cubans can be seen to have majority Spanish ancestry, and its the same for Puerto Ricans.

“Latinos/Hispanics” do not constitute a major race (in the minimalist and populationist sense) because they are a mixture of different minimalist races. This does not mean, however, that one designated as “Latino” in America does not have full ancestry to a European country; this is how the concept of “Latino” in America uses the concept of socialrace—it’s only based on the perceived race of the individual (that they derive from a “Latino” country) and that therefore makes them “Latino”, all the while ignoring their actual racial ancestry.

There is even a phrase in Latin America “Mejorar la raza” or “improve the race” by having children with lighter-skinned people since light skin is seen as beautiful in Latin America. They want to better “their race” (even though they—as “Latinos”—don’t have a race), and so they will attempt to have children with lighter and lighter people (i.e., people who have more and more European ancestry) to “improve their race” (i.e., their socialrace) since European features are seen as more beautiful in Latin America.

Most of the ruling class in Latin America is of European descent, while the lower classes are of admixed/unadmixed Indians (coming from differing tribes). This, one can say, is one way that socialrace is used in Latin America.

Conclusion

Brazilians and “Latinos/Hispanics” clearly could have been grouped in the mixed-race category, but each of these subjects has distinct concepts it needed to discuss. The Brazilian concept of “cor” and “raca” are loosely intertwined; they can be said to use aspects of mimimalist races. On the other hand, “Latinos/Hispanics” are not designated minimalist racehood on the basis that they do not share a single pattern of physical features, nor do they share a geographic origin, since the groups that make up “Latinos” (which are minimalist races) are the geographic locations in question. “Latinos/Hispanics” are not minimalist races because they do not exhibit the features of minimalist races.

Mixed-race individuals, regarding the socialrace concept, can be seen to be the “lower” of the races they are admixed with on the social ladder—which is how it is in America (the concept of hypodescent). The existence of mixed-race individuals does not invalidate the concept of race; minimalist racehood is not defined on the basis of individual characters, but on the basis of the characters of the group. Therefore this does not go against the concept of minimalist race.

The concepts of race can definitely survive these anomalies when describing the biological realities of race; some of them can be said to be socialraces for one respect, whereas in reality, they are mixtures of minimalist races. Races exist and the existence of Brazilians (even with their own categorization of races/colors) and “Latinos/Hispanics” and other mixed-race groups/individuals do not rail against any concepts that purport to argue for the existence and biological reality of race.

A Simple Argument for the Existence of Race

1550 words

Race deniers say that there is too small of a genetic distance between races to call the so-called races “races”. They latch on to Lewontin’s 1974 analysis, trumpeting that genetic distance is too small for there to be true “races”. There is, however, a simple way to bypass the useless discussions that would ensue if one cites genetic evidence for the existence of race: just use this simple argument:

P1) There are differences in patterns of visible physical features which correspond to geographic ancestry

P2) These patterns are exhibited between real groups, existing groups (i.e., individuals who share common ancestry)

P3) These real, existing groups that exhibit these physical patterns by geographic ancestry satisfy conditions of minimalist race

C) Therefore race exists and is a biological reality

This argument is simple; anyone who denies this needs to provide a good enough counter-argument, and I’m not aware of any that exist to counter the argument.

P1 shows that there are patterns of visible physical features which correspond to geographic ancestry. This is due to the climates said race evolved in over evolutionary history. Since these phenotypes are not randomly distributed across the globe, but show distinct patterning based on geographic ancestry, we can say that P1 is true; different populations show patterns of different physical features which are not randomly distributed across the globe. Further, since P1 establishes that races are populations that look different from each other, it guarantees that groups like the Amish, social classes etc are not counted as races. P1 further allows a member of a given race to not show the normative physical characters that are characteristic of that race. It further allows for the possibility that individuals from two different races may not differ in their physical characters. These visible physical characters that differ by populations we then call races also need to be heritable to be biological. “Because the visible physical features of race are heritable, the skin color, hair type, and eye shape of children of Rs tend to resemble the skin color, hair type, and eye shape of their parents” (Hardimon, 2017: 35). P1 is true.

P2 shows that these patterns of visible physical features are exhibited between real, existing groups. That is, the groups that exhibit these patterns exist in reality. No one denies this either. Differences in physical features that these real, existing groups exhibit can then be used as proxies for factors in P1. Though, like with which populations figure into this concept, the minimalist race concept doesn’t say—it only establishes the biological existence of races. “In recent years the concept of the continent has come under fire for not being well defined. 59 It is of interest that the formation of the concepts CONTINENT and RACE are roughly coeval. One wonders if the geneses of the two ideas are mutually entwined. Could it be that our idea of continent derives in part from the idea of the habitat of a racial group? Could it be that the idea of a racial group gets part of its content from the idea of a group whose aboriginal home is a distinctive continent? Perhaps the concepts should be thought of as having formed in tandem, each helping to fix the other’s reference” (Hardimon, 2017: 51). Since these real, existing populations that were geographically separated for thousands of years show these visible physical patterns, P2 is true.

P3 follows from the specification of the concept of minimalist race. If these populations that exhibit these distinct visible characters and if they are non-randomly distributed across the globe then this satisfied the argument for the concept of minimalist race. The specification of the minimalist concept of race states that groups satisfy the requisites for the concept by being distinguishable by patterns of visible physical features (P1) and that individuals who share a common ancestry peculiar to them which derive from a distinct geographic location (P2) exist as real groups. Since P1 and P2 are true, P3 follows logically from P1 and P2, which then leads us to the conclusion which is true and establishes the argument for the minimalist concept of race as a sound and valid argument.

C is then the logical conclusion of the three premises: race exists and is a biological reality since the patterns of visible physical features are non-randomly distributed across the globe and are exhibited by real, existing groups. Since all three premises are true and the conclusion is true, it is a valid argument; since the premises are true the argument is sound. No one can—logically—deny the existence of race when presented with this logical proof.

Though notice the argument doesn’t identify which populations are designated as “races” (that’s for another article), the argument just establishes that race exists and it exists as a biological reality. Notice also how this conception of race is sort of like the “racialist concept”, but it takes it down to its barest bones—only taking the normatively important, superficial biological physical features (these features establish minimalist races as biologically existing).

Notice, too, that I did not appeal to any genetic differences between the races, indeed, in my opinion, they are not needed when discussing race. All that is needed when discussing race and whether or not it is a biological reality is asking three simple questions:

1) Are there differences in patterns of visible physical features that correspond to geographic ancestry? Yes.

2) Are these patterns exhibited by real, existing groups? Yes.

3) Do these real, existing groups satisfy conditions of minimalist race? Yes

Therefore race exists.

These three simple questions (just take the premises and ask them as questions) will have one—knowingly or not—admit to the biological reality and existence of race.

Do note, though, nothing in this argument brings up anything about what we “can’t see”, meaning things like “intelligence” or mores of these races. This concept is distinct from the racialist concept in that it does not mention normatively important characters; it does not posit a relationship between visible physical characters and normatively important characters; and it does not “rank” populations on some type of scale. “Also, the conjoint fact that a group is characterized by a distinctive pattern of visible physical characteristics and consists of members who are linked by a common ancestry and originates from a distinctive geographic location is of no intrinsic normative significance. The status of being a minimalist race has no intrinsic normative significance“ (Hardimon, 2017: 32).

Clearly, one does not need to invoke genetic differences to show that race exists as a biological reality. That races differ in patterns of visible physical features which are inherited from the parents and are heritable establishes the biological reality of minimalist race. I really see no way that one could, logically, deny the existence of race given the argument provided in this article. Race exists and is a biological reality and the argument for the existence of minimalist race establishes this fact. Races differ in physiognomy and morphology; these physical differences are non-randomly distributed by geographic ancestry/at the continental level. These populations that show these physical differences share a peculiar ancestry. Knowing these facts, we can safely infer the existence of race. It is the only logical conclusion to come to. Note that the minimalist concept is deflationist—meaning that racialist races do not exist and that this concept enjoys what the racialist concept was supposed to, it is deflationary in the aspect that it takes the normative physical differences from the racialist concept. It is realist since it acknowledges the existence of minimalist race as genetically grounded and relatively superficial but still very significant biological reality of race.

Races can exist as minimalist races and socialraces—no contradiction exists. minimalist race, and its “scientific” companion populationist race (which I will cover in the future) show that there is a well-formulated argument for the existence of race (minimalist race concept) whereas the other concept shows how it is grounded in science and partitions populations to races (populationist concept; both are deflationary). (Read the descriptions of racialist race, minimalist race, populationist race, and socialrace.) You don’t need genes to delineate race; you only need a sound, valid argument based on biological principles. Minimalist races exist.

Race exists and is a biological reality, even if it is ‘socially constructed’ (what isn’t?), our social constructs still correspond to differing breeding populations who share peculiar ancestry and show patterns of visible physical features establish the existence of race.

From Hardimon (2017: 177)

(I also came across a book review from philosopher Joshua Glasgow (Book Review Rethinking Race: The Case for Deflationary Realism, by Michael O. Hardimon. Harvard University Press, 2017. Pp. 240.), author of A Theory of Race (2009) who has some pretty good critiques against Hardimon’s theses in his book, but not good enough. I am going to cover a bit more about these concepts then discuss his article. I will also cover “Latinos” and mixed race people as regards these concepts as well.)

4/19/2018 edit: Two more simple arguments:

(Where P is population, C is continent and T is trait(s)

Population P that evolved in continent C have physical traits T which correspond to C.

Minimalist Races Exist and are Biologically Real

3050 words

People look different depending on where their ancestors derived from; this is not a controversial statement, and any reasonable person would agree with that assertion. Though what most don’t realize, is that even if you assert that biological races do not exist, but allow for patterns of distinct visible physical features between human populations that then correspond with geographic ancestry, then race—as a biological reality—exists because what denotes the physical characters are biological in nature, and the geographic ancestry corresponds to physical differences between continental groups. These populations, then, can be shown to be real in genetic analyses, and that they correspond to traditional racial groups. So we can then say that Eurasian, East Asian, Oceanian, black African, and East Asians are continental-level minimalist races since they hold all of the criteria needed to be called minimalist races: (1) distinct facial characters; (2) distinct morphologic differences; and (3) they come from a unique geographic location. Therefore minimalist races exist and are a biological reality. (Note: There is more variation within races than between them (Lewontin, 1972; Rosenberg et al, 2002; Witherspoon et al, 2007; Hunley, Cabana, and Long, 2016), but this does not mean that the minimalist biological concept of race has no grounding in biology.)

Minimalist race exists

The concept of minimalist race is simple: people share a peculiar geographic ancestry unique to them, they have peculiar physiognomy (facial features like lips, facial structure, eyes, nose etc), other physical traits (hair/hair color), and a peculiar morphology. Minimalist races exist, and are biologically real since minimalist races can survive findings from population genetics. Hardimon (2017) asks, “Is the minimalist concept of race a social concept?” on page 62. He writes that social concepts are socially constructed in a pernicious sense if and only if it “(i) fails to represent any fact of the matter and (ii) supports and legitimizes domination.” Of course, populations who derive from Africa, Europe, and East Asia have peculiar facial morphology/morphology unique to that isolated population. Therefore we can say that minimalist race does not conform to criteria (i). Hardimon (2017: 63) then writes:

Because it lacks the nasty features that make the racialist concept of race well suited to support and legalize domination, the minimalist race concept fails to satisfy condition (ii). The racialist concept, on the other hand, is socially constructed in the pernicious sense. Since there are no racialist races, there are no facts of the matter it represents. So it satisfies (i). To elaborate, the racialist race concept legtizamizes racial domination by representing the social hierarchy of race as “natural” (in a value-conferring sense): as the “natural” (socially unmediated and inevitable) expression of the talent and efforts of the inidividuals who stand on its rungs. It supports racial domination by conveying the idea that no alternative arrangment of social institutions could possibly result in racial equality and hence that attempts to engage in collective action in the hopes of ending the social hierarchy of race are futile. For these reasons the racialist race concept is also idealogical in the prejorative sense.

Knowing what we know about minimalist races (they have distinct physiognomy, distinct morphology and geographic ancestry unique to that population), we can say that this is a biological phenomenon, since what makes minimalist races distinct from one another (skin color, hair color etc) are based on biological factors. We can say that brown skin, kinky hair and full lips, with sub-Saharan African ancestry, is African, while pale/light skin, straight/wavy/curly hair with thin lips, a narrow nose, and European ancestry makes the individual European.

These physical features between the races correspond to differences in geographic ancestry, and since they differ between the races on average, they are biological in nature and therefore it can be said that race is a biological phenomenon. Skin color, nose shape, hair type, morphology etc are all biological. So knowing that there is a biological basis to these physical differences between populations, we can say that minimalist races are biological, therefore we can use the term minimalist biological phenomenon of race, and it exists because there are differences in the patterns of visible physical features between human populations that correspond to geographic ancestry.

Hardimon then talks about how eliminativist philosophers and others don’t deny that above premises above the minimalist biological phenomenon of race, but they allow these to exist. Hardimon (2017: 68-69) then quotes a few prominent people who profess that there are, of course, differences in physical features between human populations:

… Lewontin … who denies that biological races exist, freely grants that “peoples who have occupied major geographic areas for much of the recent past look different from one another. Sub-Saharan Africans have dark skin and people who have lived in East Asia tend to have a light tan skin and an eye color and eye shape that is difference from Europeans.” Similarly, population geneticist Marcus W. Feldman (final author of Rosenberg et al., “Genetic Stucture of Human Populations” [2002]), who also denies the existence of biological races, acknowledges that “it has been known for centuries that certain physical features of humans are concentrated within families: hair, eye, and skin color, height, inability to digest milk, curliness of hair, and so on. These phenotypes also show obvious variation among people from different continents. Indeed, skin color, facial shape, and hair are examples of phenotypes whose variation among populations from different regions is noticeable.” In the same vein, eliminative anthropologist C. Loring Brace concedes, “It is perfectly true that long term residents of various parts of the world have patterns of features that we can identify as characteristic of they area from which they come.”

So even these people who claim to not believe in “biological races”, do indeed believe in biological races because what they are describing is biological in nature and they, of course, do not deny that people look different while their ancestors came from different places so therefore they believe in biological races. We can then use the minimalist biological phenomenon of race to get to the existence of minimalist races.

Hardimon (2017: 69) writes:

Step 1. Recognize that there are differences in patterns of visible physical features of human beings that correspond to their differences in geographic ancestry.

Step 2. Observe that these patterns are exhibited by groups (that is, real existing groups).

Step 3. Note that the groups that exhibit these patterns of visible physical features correspond to differences in geographical ancestry satisfy the conditions of the minimalist concept of race.

Step 4. Infer that minimalist race exists.

Those individuals mentioned previously who deny biological races but allow that people with ancestors from differing geographic locales look differently do not disagree with step 1, nor does anyone really disagree with step 2. Step 4’s inference immediately flows from the premise in step 3. “Groups that exhibit patterns or visible physical features that correspond to differences in geographical ancestry satisfy the conditions of the minimalist concept of race. Call (1)-(4) the argument from the minimalist biological phenomenon of race” (Hardimon, 2017: 70). Of course, the argument does not identify which populations may be called races (see further below), it just shows that race is a biological reality. Because if minimalist races exist, then races exist because minimalist races are races. Minimalist races exist, therefore biological races exist. Of course, no one doubts that people come from Europe, sub-Saharan Africa, East Asia, the Americas, and the Pacific Islands, even though the boundaries between them are ‘blurry’. They exhibit patterns of visible physical characters that correspond to their differing geographic ancestry, they are minimalist races therefore minimalist races exist.

Pretty much, the minimalist concept of race is just laying out what everyone knows and arguing for its existence. Minimalist races exist, but are they biologically real?

Minimalist races are biologically real

Of course, some who would assert that minimalist races do not exist would say that there are no ‘genes’ that are exclusive to one certain population—call them ‘race genes’. Of course, these types of genes do not exist. Whether or not one individual is a part of one race or not does not rest on the basis of his physical characters, but is determined by who his parents are, because one of the three premises for the minimalist race argument is ‘must have a peculiar geographic ancestry’. So it’s not that members of races share sets of genes that other races do not, it’s based on the fact that they share a distinctive set of visible physical features that then correspond with geographic ancestry. So of course if the minimalist concept of race is a biological concept then it entails more than ‘genes for’ races.

Of course, there is a biological significance to the existence of minimalist biological races. Consider that one of the physical characters that differ between populations is skin color. Skin color is controlled by genes (about half a dozen within and a dozen between populations). Lack of UV rays for individuals with dark skin will lead to diseases like prostate cancer, while darker skin is a protectant against UV damage to human skin (Brenner and Hearing, 2008; Jablonksi and Chaplin, 2010). Since minimalist race is biologically significant and minimalist races are partly defined by differences in skin color between populations then skin color has both medical and ecological significance.

(1) Consider light skin. People with light skin are more susceptible to skin cancer since they evolved in locations with poor UVR radiation (D’Orazio et al, 2013). The body needs vitamin D to absorb and use calcium for maintaining proper cell functioning. People who evolved near the equator don’t have to worry about this because the doses of UVB they absorb are sufficient for the production of enough previtamin D. While East Asians and Europeans on the other hand, became adapted to low-sunlight locations and therefore over time evolved lighter skin. This loss of pigmentation allowed for better UVB absorption in these new environments. (Also read my article on the evolution of human skin variation and also how skin color is not a ‘tell’ of aggression in humans.)

(2) While darker-skinned people have a lower rate of skin cancer “primarily a result of photo-protection provided by increased epidermal melanin, which filters twice as much ultraviolet (UV) radiation as does that in the epidermis of Caucasians” (Bradford, 2009). Dark skin is thought to have evolved to protect against skin cancer (Greaves, 2014a) but this has been contested (Jablonski and Chaplin, 2014) and defended (Greaves, 2014b). So therefore, using (1) and (2), skin color has evolutionary signifigance.

So as humans began becoming physically adapted to their new niches they found themselves in, they developed new features distinct from the location they previously came from to better cope with the new lifestyle due to their new environments. For instance “Northern Europeans tend to have light skin because they belong to a morphologically marked ancestral group—a minimalist race—that was subject to one set of environmental conditions (low UVR) in Europe” (Hardimon, 2017: 81). Of course explaining how human beings survived in new locations falls into the realm of biology, while minimalist races can explain why this happened.

Minimalist races clearly exist since minimalist races constitute complex biological patterns between populations. Hardimon (2017: 83) writes:

It [minimalist race] also enjoys intrinsic scientific interest because it represents distinctive salient systematic dimension of human biological diversity. To clarify: Minimalist race counts as (i) salient because human differences of color and shape are striking. Racial differences in color and shape are (ii) systematic in that they correspond to differences in geographic ancestry. They are not random. Racial differences are (iii) distinctive in that they are different from the sort of biological differences associated with the other two salient systematic dimensions of human diversity: sex and age.

[…]

An additional consideration: Like sex and age, minimalist race constitutes one member of what might be called “the triumverate of human biodiversity.” An account of human biodiversity that failed to include any one of these three elements would be obviously incomplete. Minimalist race’s claim to be biologically real is as good as the claim of the other members of the triumverate. Sex is biologically real. Age is biologically real. Minimalist race is biologically real.

Real does not mean deep. Compared to the biological associated with sex (sex as contrasted with gender), the biological differences associated with minimalist race are superficial.

Of course, the five ‘clusters’ and ‘populations’ identified by Rosenberg et al’s (2002) K=5 graph, which told structure to produce 5 genetic clusters, corresponds to Eurasia, Africa, East Asia, Oceania, and the Americas, are great candidates for minimalist biological races since they correspond to geographic locations, and even corroborates what Fredrich Blumenbach said about human races back in the 17th century. Hardimon further writes (pg 85-86):

If the five populations corresponding to the major areas are continental-level minimalist races, the clusters represent continental-level minimalist races: The cluster in the mostly orange segment represents the sub-Saharan African continental-level minimalist race. The cluster in the mostly blue segment represents the Eurasian continental-level minimal race. The cluster in the mostly pink segment represents the East Asian continental-level minimalist race. The cluster in the mostly green segment represents the Pacific Islander continental-level minimalist race. And the cluster in the mostly purple segment represents the American continental-level minimalist race.

[…]

The assumption that the five populations are continental-level minimalist races entitles us to interpret structure as having the capacity to assign individuals to continental-level minimalist races on the basis of markers that track ancestry. In constructing clusters corresponding to the five continental-level minimalist races on the basis of objective, race-neutral genetic markers, structure essentially “reconstructs” those races on the basis of a race-blind procedure. Modulo our assumption, the article shows that it is possible to assign individuals to continental-level races without knowing anything about the race or ancestry of the individuals from whose genotypes the microsattelites are drawn. The populations studied were “defined by geography, language, and culture,” not skin color or “race.”

Of course, as critics note, the researchers predetermine how many populations that structure demarcates, for instance, K=5 indicates that the researchers told the program to delineate 5 clusters. Though, these objections do not matter. For the 5 populations that come out in K=5 “are genetically structured … which is to say, meaningfully demarcated solely on the basis of genetic markers” (Hardimon, 2017: 88). K=6 brings one more population, the Kalash, a group from northern Pakistan who speak an Indo-European language. Though “The fact that structure represents a population as genetically distinct does not entail that the population is a race. Nor is the idea that populations corresponding to the five major geographic areas are minimalist races undercut by the fact that structure picks out the Kalash as a genetically distinct group. Like the K=5 graph, the K=6 graph shows that modulo our assumption, continental-level races are genetically structured” (Hardimon, 2017: 88).

Though of course there are naysayers. Svante Paabo and David Serre, Hardimon writes, state that when individuals are sampled from homogeneous populations from around the world, the gradients of the allele frequencies that are found are distributed randomly across the world rather than clustering discretely. Though Rosenberg et al responded by verifying that the clusters they found are not artifacts of sampling as Paabo and Serre imply, but reflect features of underlying human variation. Though Rosenberg et al agree with Paabo and Serre in that that human genetic diversity consists of clines in variation in allele frequencies (Hardimon, 2017: 89). Other naysayers also state that all Rosenberg et al show is what we can “see with our eyes”. Though a computer does not partition individuals into different populations based on something that can be done with eyes, it’s based on an algorithm.

Hardimon also accepts that black Africans, Caucasians, East Asians, American Indians and Oceanians can be said to be races in the basic sense because “they constitute a partition of the human species“, and that they are distinguishable “at the level of the gene” (Hardimon, 2017: 93). And of course, K=5 shows that the 5 races are genetically distinguishable.

Hardimon finally discusses some medical significance for minimalist races. He states that if you are Caucasian that it is more likely that you have a polymorphism that protects against HIV compared to a member of another race. Meanwhile, East Asians are more likely to carry alleles that make them more susceptible to Steven-Johnson syndrome or another syndrome where their skin falls off. Though of course, the instances where this would matter in a biomedical context are rare, but still should be at the back of everyone’s mind (as I have argued), even though instances where medical differences between minimalist races are rare, there are times where one’s race can be medically significant.

Hardimon finally states that this type of “metaphysics of biological race” can be called “deflationary realism.” Deflationary because it “consists in the repudiation of the ideas that racialist races exist and that race enjoys the kind of biological reality that racialist race was supposed to have” and realism which “consists in its acknowledgement of the existence of minimalist races and the genetically grounded, relatively superficial, but still significant biological reality of minimalist race” (Hardimon, 2017: 95-96).

Conclusion

Minimalist races exist. Minimalist races are a biological reality because distinct visible patterns show differences between geographically isolated populations. This is enough for the classification of the five classic races we know of to be called race, be biologically real, and have a medical significance—however small—because certain biological/physical traits are tied to different geographic populations—minimalist races.

Hardimon (2017: 97) shows an alternative to racialism:

Deflationary realism provides a worked-out alternative to racialism—it it a theory that represents race as a genetically grounded, relatively superficial biological reality that is not normatively important in itself. Deflationary realism makes it possible to rethink race. It offers the promise of freeing ourselves, if only imperfectly, from the racialist background conception of race.

It is clear that minimalist races exist and are biologically real. You do not need to speak about supposed mental traits between these minimalist races, they are irrelevant to the existence of these minimalist biological races. As Hardimon (2017: 67) writes: “No reference is made to normatively important features such as intelligence, sexuality, or morality. No reference is made to essences. The idea of sharp boundaries between patterns of visible physical features or corresponding geographical regions is not invoked. Nor again is reference made to the idea of significant genetic differences. No reference is made to groups that exhibit patterns of visible physical features that correspond to geographic ancestry.”

The minimalist biological concept of race stands up to numerous lines of argumentation, therefore we can say without a shadow of a doubt that minimalist biological race exists and is real.