Home » Race Realism (Page 8)

Category Archives: Race Realism

The “World’s Smartest Man” Christopher Langan on Koko the Gorilla’s IQ

1500 words

Christopher Langan is purported to have the highest IQ in the world, at 195—though comparisons to Wittgenstein (“estimated IQ” of 190), da Vinci, and Descartes on their “IQs” are unfounded. He and others are responsible for starting the high IQ society the Mega foundation for people with IQs of 164 or above. For a man with one of the highest IQs in the world, he lived on a poverty wage at less than $10,000 per year in 2001. He has also been a bouncer for the past twenty years.

Koko is one of the world’s most famous gorillas, most-known for crying when she was told her cat got hit by a car and being friends with Robin Williams, also apparently expressing sadness upon learning of his death. Koko’s IQ, as measured by an infant IQ test, was said to be on-par or higher than some of the (shoddy) national IQ scores from Richard Lynn (Richardson, 2004; Morse, 2008). This then prompted white nationalist/alt-right groups to compare Koko’s IQ scores with that of certain nationalities and proclaim that Koko was more ‘intelligent’ than those nationalities on the basis of her IQ score. But, unfortunately for them, the claims do not hold up.

The “World’s Smartest Man” Christopher Langan is one who falls prey to this kind of thinking. He was “banned from” Facebook for writing a post comparing Koko’s IQ scores to that of Somalians, asking why we don’t admit gorillas into our civilization if we are letting Somalian refugees into the West:

“According to the “30 point rule” of psychometrics (as proposed by pioneering psychometrician Leta S. Holingsworth), Koko’s elevated level of thought would have been all but incomprehensible to nearly half the population of Somalia (average IQ 68). Yet the nation’s of Europe and North America are being flooded with millions of unvetted Somalian refugees who are not (initially) kept in cages despite what appears to be the world’s highest rate of violent crime.

Obviously, this raises the question: Why is Western Civilization not admitting gorillas? They too are from Africa, and probably have a group mean IQ at least equal to that of Somalia. In addition, they have peaceful and environmentally friendly cultures, commit far less violent crime than Somalians…”

I presume that Langan is working off the assumption that Koko’s IQ is 95. I also presume that he has seen memes such as this one floating around:

There are a few problems with Langan’s claims, however. (1) The notion of a “30-point IQ point communication” rule—that one’s own IQ, plus or minus 30 points, denotes where two people can understand each other; and (2) bringing up Koko’s IQ and the comparing it to “Somalians.”

It seems intuitive to the IQ-ist that a large, 2 SD gap in IQ between people will mean that more often than not there will be little understanding between them if they talk, as well as the kinds of interests they have. Neuroskeptic looked into the origins of the claim of the communication gap in IQ, found it to be attributed to Leta Hollingworth and elucidated by Grady Towers. Towers noted that “a leadership pattern will not form—or it will break up—when a discrepancy of more than about 30 points comes to exist between leader and lead.” Neuroskeptic comments:

This seems to me a significant logical leap. Hollingworth was writing specifically about leadership, and in childen [sic], but Towers extrapolates the point to claim that any kind of ‘genuine’ communication is impossible across a 30 IQ point gap.

It is worth noting that although Hollingworth was an academic psychologist, her remark about leadership does not seem to have been stated as a scientific conclusion from research, but simply as an ‘observation’.

[…]

So as far as I can see the ‘communication range’ is just an idea someone came up with. It’s not based on data. The reference to specific numbers (“+/- 2 standard deviations, 30 points”) gives the illusion of scientific precision, but these numbers were plucked from the air.

The notion that Koko had an “elevated level of thought [that] would have been all but incomprehensible to nearly half the population of Somalia (average IQ 68)” (Langan) is therefore laughable, not only for the reason that a so-called communication gap is false, but for the simple fact that Koko’s IQ was tested using the Cattell Infant Intelligence Scales (CIIS) (Patterson and Linden,1981: 100). It seems to me that Langan has not read the book that Koko’s handlers wrote about her—The Education of Koko (Patterson and Linden, 1981)—since they describe why Koko’s score should not be compared with human infants, so it follows that her score cannot be compared with human adults.

The CIIS was developed “to a downward extension of the Stanford-Binet” (Hooper, Conner, and Umansky, 1986), and so, it must correlate highly with the Stanford-Binet in order to be “valid” (the psychometric benchmark for validity—correlating a new test with the most up-to-date test which had assumed validity; Richardson, 1991, 2000, 2017; Howe, 1997). Hooper, Conner, and Umansky (1986: 160) note in their review of the CIIS, “Given these few strengths and numerous shortcomings, salvaging the Cattell would be a major undertaking with questionable yield. . . . Nonetheless, without more research investigating this instrument, and with the advent of psychometrically superior measures of infant development, the Cattell may be relegated to the role of an historical antecedent.” Items selected for the CIIS—like all IQ tests—“followed a quasi-statistical approach with many items being accepted and rejected subjectively.” They state that many of the items on the CIIS need to be updated with “objective” item analysis—but, as Jensen notes, items emerge arbitrarily from the heads of the test’s constructors.

Patterson—the woman who raised Koko—notes that she “tried to gauge [Koko’s] performance by every available yardstick, and this meant administering infant IQ tests” (Patterson and Linden, 1981: 96). Patterson and Linden (1981: 100) note that Koko did better than human counterparts of her age in certain tasks over others, for example “her ability to complete logical progressions like the Ravens Progressive Matrices test” since she pointed to the answer with no hesitation.

Koko generally performed worse than children when a verbal rather than a pointing response was required. When tasks involved detailed drawings, such as penciling a path through a maze, or precise coordination, such as fitting puzzle pieces together. Koko’s performance was distinctly inferior to that of children.

[…]

It is hard to draw any firm conclusions about the gorilla’s intelligence as compared to that of the human child. Because infant intelligence tests have so much to do with motor control, results tend to get skewed. Gorillas and chimps seem to gain general control over their bodies earlier than humans, although ultimately children far outpace both in the fine coordination required in drawing or writing. In problems involving more abstract reasoning, Koko, when she is willing to play the game, is capable of solving relatively complex problems. If nothing else, the increase in Koko’s mental age shows that she is capable of understanding a number of the principles that are the foundation of what we call abstract thought. (Patterson and Linden, 1981: 100-101)

They conclude that “it is specious to compare her IQ directly with that of a human infant” since gorillas develop motor skills earlier than human infants. So if it is “specious” to compare Koko’s IQ with an infant, then it is “specious” to compare Koko’s IQ with the average Somalian—as Langan does.

There have been many critics of Koko, and similar apes, of course. One criticism was that Koko was coaxed into signing the word she signed by asking Koko certain questions, to Robert Sapolsky stating that Patterson corrected Koko’s signs. She, therefore, would not actually know what she was signing, she was just doing what she was told. Of course, caregivers of primates with the supposed extraordinary ability for complex (humanlike) cognition will defend their interpretations of their observations since they are emotionally invested in the interpretations. Patterson’s Ph.D. research was on Koko and her supposed capabilities for language, too.

Perhaps the strongest criticism of these kinds of interpretations of Koko comes from Terrace et al (1979). Terrace et al (1979: 899) write:

The Nova film, which also shows Ally (Nim’s full brother) and Koko, reveals a similar tendency for the teacher to sign before the ape signs. Ninety-two percent of Ally’s, and all of Koko’s, signs were signed by the teacher immediately before Ally and Koko signed.

It seems that Langan has never done any kind of reading on Koko, the tests she was administered, nor the problems in comparing them to humans (infants). The fact that Koko seemed to be influenced by her handlers to “sign” what they wanted her to sign, too, makes interpretations of her IQ scores problematic. For if Koko were influenced what to sign, then we, therefore, cannot trust her scores on the CIIS. The false claims of Langan are laughable knowing the truth about Koko’s IQ, what her handlers said about her IQ, and knowing what critics have said about Koko and her sign language. In any case, Langan did not show his “high IQ” with such idiotic statements.

China’s Project Coast?

1250 words

Project Coast was a secret biological/chemical weapons program developed by the apartheid government in South Africa started by a cardiologist named Wouter Basson. One of the many things they attempted was to develop a bio-chemical weapon that targets blacks and only blacks.

I used to listen to the Alex Jones show in the beginning of the decade and in one of his rants, he brought up Project Coast and how they attempted to develop a weapon to only target blacks. So I looked into it, and there is some truth to it.

For instance, The Washington Times writes in their article Biotoxins Fall Into Private Hands:

More sinister were the attempts — ordered by Basson — to use science against the country’s black majority population. Daan Goosen, former director of Project Coast’s biological research division, said he was ordered by Basson to develop ways to suppress population growth among blacks, perhaps by secretly applying contraceptives to drinking water. Basson also urged scientists to search for a “black bomb,” a biological weapon that would select targets based on skin color, he said.

“Basson was very interested. He said ‘If you can do this, it would be very good,'” Goosen recalled. “But nothing came of it.”

They created novel ways to disperse the toxins: using letters and cigarettes to transmit anthrax to black communities (something those old enough to be alive during 911 know of), lacing sugar cubes with salmonella, lacing beer and peppermint candy with poison.

Project Coast was, at its heart, a eugenics program (Singh, 2008). Singh (2008: 9) writes, for example that “Project Coast also speaks for the need for those involved in scientific research and practice to be sensitized to appreciate the social circumstances and particular factors that precipitate a loss of moral perspective on one’s actions.”

Jackson (2015) states that another objective of the Project was to develop anti-fertility drugs and attempt to distribute them into the black population in South Africa to decrease birth rates. They also attempted to create vaccines to make black women sterile to decrease the black population in South Africa in a few generations—along with attempting to create weapons to only target blacks.

The head of the weapons program, Wouter Basson, is even thought to have developed HIV with help from the CIA to cull the black population (Nattrass, 2012). There are many conspiracy theories that involve HIV and its creation to cull black populations, though they are pretty farfetched. In any case, though, since they were attempting to develop new kinds of bioweapons to target certain populations, it’s not out of the realm of possibility that there is a kernel of truth to the story.

So now we come to today. So Kyle Bass said that the Chinese already have access to all of our genomes, through companies like Steve Hsu’s BGI, stating that “there’s a Chinese company called BGI that does the overwhelming majority of all the sequencing of U.S. genes. … China had the genomic sequence of every single person that’s been gene types in the U.S., and they’re developing bio weapons that only affect Caucasians.”

I have no way to verify these claims (they’re probably bullshit), but with what went on in the 80s and 90s in South Africa with Project Coast, I don’t believe it’s outside of the realm of plausibility. Though Caucasians are a broad grouping.

It’d be like if someone attempted to develop a bioweapon that only targets Ashkenazi Jews. They could let’s say, attempt to make a bioweapon to target those with Tay Sach’s disease. It’s, majorly, a Jewish disease, though it’s also prevalent in other populations, like French Canadians. It’d be like if someone attempted to develop a bioweapon that only targets those with the sickle cell trait (SCT). Certain African ethnies are more like to carry the trait, but it’s also prevalent in southern Europe and Northern Africa since the trait is prevalent in areas with many mosquitoes.

With Chinese scientists like He Jiankui CRISPR-ing two Chinese twins back in 2018 to attempt to edit their genome to make them less susceptible to HIV, I can see a scientist in China attempt to do something like this. In our increasingly technological world with all of these new tools we develop, I would be surprised if there was nothing strange like this going on.

Some claim that “China will always be bad at bioethics“:

Even when ethics boards exist, conflicts of interest are rife. While the Ministry of Health’s ethics guidelines state that ethical reviews are “based upon the principles of ethics accepted by the international community,” they lack enforcement mechanisms and provide few instructions for investigators. As a result, the ethics review process is often reduced to a formality, “a rubber stamp” in Hu’s words. The lax ethical environment has led many to consider China the “Wild East” in biomedical research. Widely criticized and rejected by Western institutions, the Italian surgeon Sergio Canavero found a home for his radical quest to perform the first human head transplant in the northern Chinese city of Harbin. Canavero’s Chinese partner, Ren Xiaoping, although specifying that human trials were a long way off, justified the controversial experiment on technological grounds, “I am a scientist, not an ethical expert.” As the Chinese government props up the pseudoscience of traditional Chinese medicine as a valid “Eastern” alternative to anatomy-based “Western” medicine, the utterly unscientific approach makes the establishment of biomedical regulations and their enforcement even more difficult.

Chinese ethicists, though, did respond to the charge of a ‘Wild East’, writing:

Some commentators consider Dr. He’s wrongdoings as evidence of a “Wild East” in scientific ethics or bioethics. This conclusion is not based on facts but on stereotypes and is not the whole story. In the era of globalization, rule-breaking is not limited to the East. Several cases of rule-breaking in research involved both the East and the West.

Henning (2006) notes that “bioethical issues in China are well covered by various national guidelines and regulations, which are clearly defined and adhere to internationally recognized standards. However, the implementation of these rules remains difficult, because they provide only limited detailed instructions for investigators.” With a large country like China, of course, it will be hard to implement guidelines on a wide-scale.

Gene-edited humans were going to come sooner or later, but the way that Jiankui went about it was all wrong. Jiankjui raised funds, dodged supervision and organized researchers in order to carry out the gene-editing on the Chinese twins. “Mad scientists” are, no doubt, in many places in many countries. “… the Chinese state is not fundamentally interested in fostering a culture of respect for human dignity. Thus, observing bioethical norms run second.”

Countries attempting to develop bioweapons to target specific groups of people have already been attempted recently, so I wouldn’t doubt that someone, somewhere, is attempting something along these lines. Maybe it is happening in China, a ‘Wild East’ of low regulations and oversight. There is a bioethical divide when it comes to East and West, which I would chalk up to differences in collectivism vs individualism (which some have claimed to be ‘genetic’ in nature; Kiaris, 2012). Since the West is more individualistic, they would care about individual embryos which eventually become a person; since the East is more collectivist, whatever is better for the group (that is, whatever can eventually make the group ‘better’) will override the individual and so, tinkering with individual genomes would be seen as less of an ethical charge to them.

A Systems View of Kenyan Success in Distance Running

1550 words

The causes of sporting success are multi-factorial, with no cause being more important than the other since the whole system needs to work in concert to produce the athletic phenotype–call this “causal parity” of athletic success determinants. For a refresher, take what Shenk (2010: 107):

As the search for athletic genes continues, therefore, the overwhelming evidence suggests that researchers will instead locate genes prone to certain types of interactions: gene variant A in combination with gene variant B, provoked into expression by X amount of training + Y altitude + Z will to win + a hundred other life variables (coaching, injuries, etc.), will produce some specific result R. What this means, of course, What this means, of course, is that we need to dispense rhetorically with thick firewall between biology (nature) and training (nurture). The reality of GxE assures that each person’s genes interacts with his climate, altitude, culture, meals, language, customs and spirituality—everything—to produce unique lifestyle trajectories. Genes play a critical role, but as dynamic instruments, not a fixed blueprint. A seven- or fourteen- or twenty-eight-year-old is not that way merely because of genetic instruction. (Shenk, 2010: 107) [Also read my article Explaining African Running Success Through a Systems View.]

This is how athletic success needs to be looked at; not reducing it to genes or a group of genes that ’cause’ athletic success. Since to be successful in the sport of the athlete’s choice takes more than being born with “the right” genes.

Recently, a Kenyan woman—Joyciline Jepkosgei—won the NYC marathon in here debut (November 3rd, 2019), while Eliud Kipchoge—another Kenyan—became the first human ever to complete a marathon (26.2 miles) in under 2 hours. I recall in the spring reading that he said he would break the 2-hour mark in October. He also attempted to break it in 2017 in Italy but, of course, he failed. His official time in Italy was 2:00:25! While he set the world record in Berlin at 2:01:39. Kipchoge’s official time was 1:59:40—twenty seconds shy of 2 hours—that means his average mile pace was about 4 minutes and 34 seconds. That is insane. (But the IAAF does not accept the time as a new world record since it was not in an open competition—Kipchoge had a slew of Olympic pacesetters following him; an electric car drove just ahead of him and pointed lasers at the ground showing him where to run; so he shaved 2 minutes off his time—2 crucial minutes—according to sport scientist Ross Tucker; and . So he did not set a world record. His feat, though, is still impressive.)

Now, Kipchoge is Kenyan—but what’s his ethnicity? Surprise surprise! He is of the Nandi tribe, more specifically, of the Talai subgroup, born in Kapsisiywa in the Nandi county. Jepkosgei, too, is Nandi, from Cheptil in Nandi county. (Jepkosgei also set the record for the half marathon in 2017. Also, see her regular training regimen and what she does throughout the day. This, of course, is how she is able to be so elite—without hard training, even without “the right genetic makeup”, one will not become an elite athlete.) What a strange coincidence that these two individuals who won recent marathons—and one who set the best time ever in the 26.2 mile race—are both Kenyan, specifically Nandi?

Both of these runners are from the same county in Kenya. Nandi county is elevated about 6,716 ft above sea level. Being born and living at a high elevation means that they have different kinds of physiological adaptations due to being born at such a higher elevation. Living and training at such high elevations means that they have greater lung capacities since they are breathing in thinner air. Those born in highlands like Kipchoge and Jepkosgei have larger lungs and thorax volumes, while oxygen intake is enhanced by increases in lung compliance, pulmonary diffusion, and ventilation (Meer, Heymans, and Zijlstra, 1995).

Those exposed to such elevation develop what is known as “high-altitude hypoxia.” Humans born at high altitudes are able to cope with such a lack of oxygen, since our physiological systems are dynamic—not static—and can respond to environmental changes within seconds of them occurring. Babes born at higher elevations have increased ventilation, and a rise in the alveolar and the pressure of arterial oxygen (Meer, Heymans, and Zjilstra, 1995).

Kenyans have 5 percent longer legs and 12 percent lighter muscles than Scandinavians (Suchy and Waic, 2017). Mooses et al (2014) notes that “upper leg length, total leg length and total leg length to body height ratio were correlated with running performance.” Kong and de Heer (2008) note that:

The slim limbs of Kenyan distance runners may positively contribute to performance by having a low moment of inertia and thus requiring less muscular effort in leg swing. The short ground contact time observed may be related to good running economy since there is less time for the braking force to decelerate forward motion of the body.

An abundance of type I muscle fibers is conducive to success in distance running (Zierath and Hawley, 2004), though Kenyans and Caucasians have no difference in type I muscle fibers (Saltin et al, 1995; Larsen and Sheel, 2015). That, then, throws a wrench in the claim that a whole slew of anatomic and physiologic variables conducive to running success is the cause for Kenyan running success—specifically the type I fibers—right? Wrong. Recall that the appearance of the athletic phenotype is due to nature and nurture—genes and environment—working together in concert. Kenyans are more likely to have slim, long limbs with lower body fat while they lived and trained over 6000 ft high. Their will to win to better themselves and their families’ socioeconomic status, too, plays a part. As I have argued in-depth for years—we cannot understand athletic success and elite athleticism without understanding individual histories, how they grew up, and what they did as a child.

For example, Wilbur and Pitsiladis (2012) espouse a systems view of Kenyan marathon success, writing:

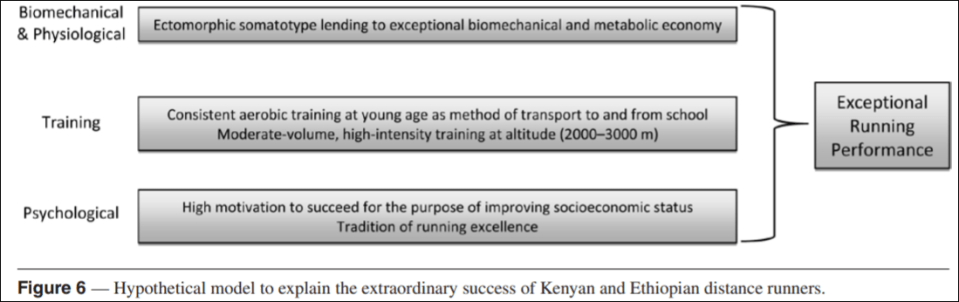

In general, it appears that Kenyan and Ethiopian distance-running success is not based on a unique genetic or physiological characteristic. Rather, it appears to be the result of favorable somatotypical characteristics lending to exceptional biomechanical and metabolic economy/efficiency; chronic exposure to altitude in combination with moderate-volume, high-intensity training (live high + train high), and a strong psychological motivation to succeed athletically for the purpose of economic and social advancement.

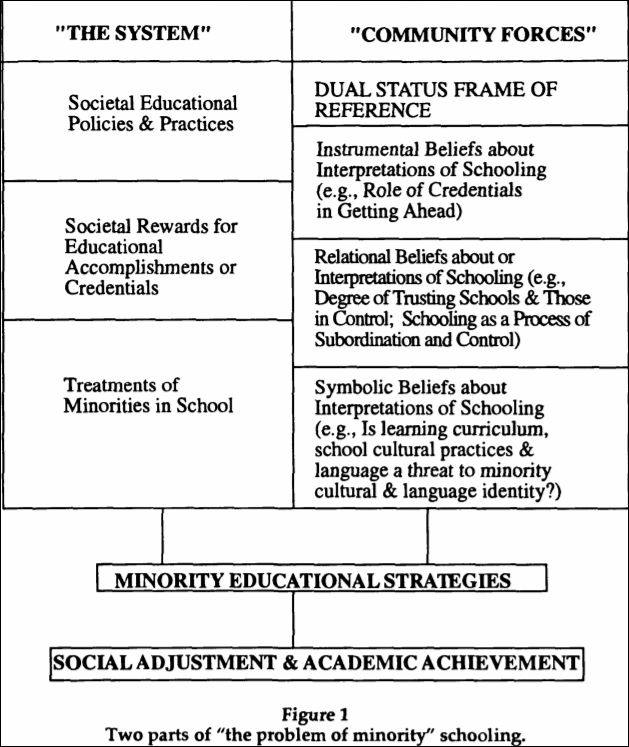

Becoming a successful runner in Kenya can lead to economic opportunities not afforded to those who do not do well in running. This, too, is a factor in Kenyan running success. So, for the ignorant people who would—pushing a false dichotomy of genes and environment—state that Kenyan running success is due to “socioeconomic status”—they are right, to a point (even if they are mocking it and making their genetic determinism seem more palatable). See figure 6 for their hypothetical model:

This is one of the best models I have come across explaining the success of these people. One can see that it is not reductonist; note that there is no appeal to genes (just variables that genes are implicated IN! Which is not the same as reductionism). It’s not as if one can have an endomorphic somatotype with Kenyan training and their psychological reasons for becoming runners. The ecto-dominant somatotype is a necessary factor for success; but all four of these—biomechanical & physiological, training, and psychological—factors explain the success of the running Kenyans and, in turn, the success of Kipchoge and Jepkosgei. African dominance in distance running is, also, dominated by the Nandi subtribe (Tucker, Onywera, and Santos-Concejero, 2015). Knechtle et al (2016) also note that male and female Kenyan and Ethiopian runners are the youngest and fast at the half and full marathons.

The actual environment—climate—on the day of the race, too plays a factor. El Helou et al (2012) note that “Air temperature is the most important factor influencing marathon running performance for runners of all levels.” Nikolaidis et al (2019) note that “race times in the Boston Marathon are influenced by temperature, pressure, precipitations, WBGT, wind coming from the West and wind speed.”

The success of Kenyans—and other groups—shows how the dictum “Athleticism is irreducible to biology” (St. Louis, 2004) is true. How does it make any sense to attempt to reduce athletic success down to one variable and say that that explains the overrepresentation of, say, Kenyans in distance running? A whole slew of factors needs to occur to an individual, along with actually wanting to do something, in order for them to succeed at distance running.

So, what makes Kenyans like Kipchoge and Jepkosgei so good at distance running? It’s due to an interaction with genes and environment, since we take a systems and not a reductionist view of sport success. Even though Kipchoge’s time does not count as an official world record, what he did was still impressive (though not as impressive if he would have done so without all of the help he had). Looking at the system, and not trying to reduce the system to its parts, is how we will explain why some groups are better than others. Genes, of course, play a role in the ontogeny of the athletic phenotype, but they are not the be-all-end-all that genetic reductionists seem to make it out to be. The systems view for Kenyan running success shown here is how and why Kenyans—Kipchoge and Jepkosgei—dominate distance running.

Genetic and Epigenetic Determinism

1550 words

Genetic determinism is the belief that behavior/mental abilities are ‘controlled by’ genes. Gerick et al (2017) note that “Genetic determinism can be described as the attribution of the formation of traits to genes, where genes are ascribed more causal power than what scientific consensus suggests“, which is similar to Oyama (1985) who writes “Just as traditional though placed biological forms in the mind of God, so modern thought finds ways of endowing genes with ultimate formative power.” Moore (2014: 15) notes that genetic determinism is “the idea that genes can determine the nature of our characteristics” or “the old idea that biology controls the development of characteristics like intelligence, height, and personality” (pg 39). (See my article DNA is not a Blueprint for more information.)

On the other hand, epigenetic determinism is “the belief that epigenetic mechanisms determine the expression of human traits and behaviors” (Wagoner and Uller, 2016). Both views are, of course, espoused in the scientific literature as well as usual social discourse. Both views, as well, are false. Moore (2014: 245) notes that epigenetic determinism is “the idea that an organism’s epigenetic state invariably leads to a particular phenotype.”

Genetic Determinism

The concept of genetic determinism was first proposed by Weismann in 1893 with a theory of germplasm. This, in contemporary times, is contrasted with “blank slatism” (Pinker, 2002), or the Standard Social Science Model (SSSM; Tooby and Cosmides, 1992; see Richardson, 2008 for a response). Genes, genetic determinists hold, determine the ontogeny of traits, being a sort of “director.” But this betrays modern thinking on genes, what they are, and what they “do.” Genes do nothing on their own without input from the physiological system—that is, from the environment (Noble, 2011). Thus, gene-environment interaction is the rule.

This lead to either-or thinking in regard to the origin of traits and their development—what we now call “the nature-nurture debate.” Nature (genes/biology) or nurture (experience, how one is raised), gene determinists hold, are the cause of certain traits, like, for example, IQ.

Plomin (2018) asserts that nature has won the battle over nurture—while also stating that they interact. So, which one is it? It’s obvious that they interact—if there were no genes there would still be an environment but if there were no environment there would be no genes. (See here and here for critiques of his book Blueprint.)

This belief that genes determine traits goes back to Galton—one of the first hereditarians. Indeed, Galton was the one to coin the phrase “nature vs nurture”, while being a proponent of ‘nature over nurture.’ Do genes or environment influence/cause human behavior? The obvious answer to the question is both do—and they are intertwined: they interact.

Griffiths (2002) notes that:

Genetic determinism is the idea that many significant human characteristics are rendered inevitable by the presence of certain genes; that it is futile to attempt to modify criminal behavior or obesity or alcoholism by any means other than genetic manipulation.

Griffiths then argues that genes are very unlikely to be deterministic causes of behavior. Genes are thought to have a kind of “information” in them which then determines how the organism will develop. This is what the “blueprint metaphor” for genes attempts to show. Genes contain this information for trait development. The implicit assumption here is that genes are context-independent—that the (environmental) context the organism is in does not matter. But genes are context-dependent—“the very concept of a gene requires the environment” (Schneider, 2007). This speaks to the context-dependency of genes. There is no “information”—genes are not like blueprints or recipes. So genetic determinism is false.

But even though genetic determinism is false, it still stays in the minds of our society/culture and scientists (Moore, 2008), while still being taught in schools (Jamieson and Radick, 2017).

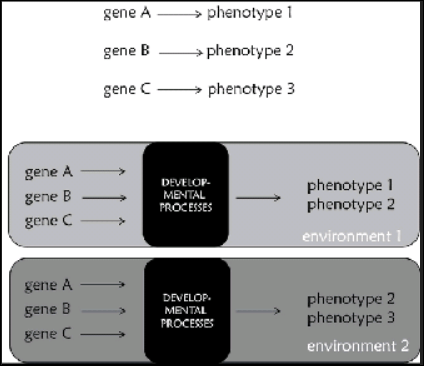

The claim that genes determine phenotypes can be shown in the following figure from Kampourakis (2017: 187):

Figure 9.6 (a) The common representation of gene function: a single gene determines a single phenotype. It should be clear by what has been present in the book so far that is not accurate. (b) A more accurate representation of gene function that takes development and environment into account. In this case, a phenotype is produced in a particular environment by developmental processes in which genes are implicated. In a different environment the same genes might contribute to the development of a different phenotype. Note the “black box” of development.

Richardson (2017: 133) notes that “There is no direct command line between environments and genes or between genes and phenotypes.” The fact of the matter is, genes do not determine an organism’s characters, they are merely implicated in the development of the character—being passive, not active templates (Noble, 2011).

Moore (2014: 199) tells us how genetic determinism fails since genes do not work in a vaccuum:

There is just one problem with the neo-Darwinian assumption that “hard” inheritance is the only good explanation for the transgenerational transmission of phenotypes: It is hopelessly simplistic. Genetic determinism is a faulty idea, because genes do not operate in a vacuum; phenotypes develop when genes interact with nongenetic factors in their local environments, factors that are affected by the broader environment.

Epigenetic Determinism

On the other hand, epigenetic determinism, the belief that epigenetic mechanisms determine the behavior of the organism, is false but in the other direction. Epigenetic determinists decry genetic determinism, but I don’t think they realize that they are just as deterministic as they are.

Dupras et al (2018) note how “overly deterministic readings of epigenetic marks could promote discriminatory attitudes, discourses and practices based on the predictive nature of epigenetic information.” While epigenetics—specifically behavioral epigenetics—refutes notions of genetic determinism, we can then fall into a similar trap, but determinism all the same. This means, though, that since genes don’t determine, epigenetics does not either, so we cannot epigenetically manipulate pre- or perinatally since what we would attempt to manipulate—‘intelligence’, contentment, happiness—all develop over the lifespan. Moore (2014: 248) continues:

Even in situations where we know that certain perinatal experiences can have very long-term effects, determinism is still an inappropriate framework for thinking about human development. For example, no one doubts that drinking alcohol during pregnancy is bad for the fetus, but in the hundreds of years before scientists established this relationship, innumerable fetuses exposed to some alcohol nonetheless grew up to be healthy, normal adults. This does not mean that pregnant women should drink alcohol freely, of course, but it does mean that developmental outcomes are not as easy to predict as we sometimes think. Therefore, it is probably always a bad idea to apply a deterministic worldview to a human being. Like DNA segments, epigenetic marks should not be considered destiny. How a given child will develop after trauma, for example, depends on a lot more than simply the experience of the trauma itself.

In an interview with The Psych Report Moore tells us that people not know enough about epigenetics for there to be epigenetic determinists (though many journalists and some scientists talk like they are :

I don’t think people know enough about epigenetics yet to be epigenetic determinists, but I foresee that as a problem. As soon as people start hearing about these kinds of data that suggest that your early experiences can have long-term effects, there’s a natural assumption we all make that those experiences are determinative. That is, we tend to assume that if you have this experience in poverty, you are going to be permanently scarred by it.

The data seem to suggest that it may work that way, but it also seems to be the case that the experiences we have later in life also have epigenetic effects. And there’s every reason to think that those later experiences can ameliorate some of the effects that happened early on. So, I don’t think we need to be overly concerned that the things that happen to us early in life necessarily fate us to certain kinds of outcomes.

While epigenetics refutes genetic determinism, we can run into the problem of epigenetic determinism, which Moore predicts. But journalists note how genes can be turned on or off by the environment, thereby dictating disease states, for example. Though, biological determinism—of any kind, epigenetic or genetic—is nonsensical as “the development of phenotypes depends on the contexts in which epigenetic marks (and other developmentally relevant factors, of course, are embedded” (Moore, 2014: 246).

What really happens?

What really happens regarding development if genetic and epigenetic determinism are false? It’s simple: causal parity (Oyama, 1985; Noble, 2012): the thesis that genes/DNA play an important role in development, but so do other variables, so there is no reason to privilege genes/DNA above other developmental variables. Genes are not special developmental resources and so, nor are they more important than other developmental resources. So the thesis is that genes and other developmental resources are developmentally ‘on par’. ALL traits develop through an interaction between genes and environment—nature and nurture. Contra ignorant pontifications (e.g., Plomin), neither has “won out”—they need each other to produce phenotypes.

So, genetic and epigenetic determinism are incoherent concepts: nature and nurture interact to produce the phenotypes we see around us today. Developmental systems theory, which integrates all factors of development, including epigenetics, is the superior framework to work with, but we should not, of course, be deterministic about organismal development.

A not uncommon reaction to DST is, ‘‘That’s completely crazy, and besides, I already knew it.” — Oyama, 2000, 195, Evolution’s Eye

Hereditarian “Reasoning” on Race

1100 words

The existence of race is important for the hereditarian paradigm. Since it is so important, there must be some theories of race that hereditarians use to ground their theories of race and IQ, right? Well, looking at the main hereditarians’ writings, they just assume the existence of race, and, along with the assumption, the existence of three races—Caucasoid, Negroid, and Mongoloid, to use Rushton’s (1997) terminology.

But just assuming race exists without a definition of what race is is troubling for the hereditarian position. Why just assume that race exists?

Fish (2002: 6) in Race and Intelligence: Separating Science from Myth critiques the usual hereditarians on what race is and their assumptions that it exists. He cites Jensen (1998: 425) who writes:

A race is one of a number of statistically distinguishable groups in which individual membership is not mutually exclusive by any single criterion, and individuals in a given group differ only statistically from one another and from the group’s central tendency on each of the many imperfectly correlated genetic characteristics that distinguish between groups as such.

Fish (2002: 6) continues:

This is an example of the kind of ethnocentric operational definition described earlier. A fair translation is, “As an American, I know that blacks and whites are races, so even though I can’t find any way of making sense of the biological facts, I’ll assign people to my cultural categories, do my statistical tests, and explain the differences in biological terms.” In essence, the process involves a kind of reasoning by converse. Instead of arguing, “If races exist there are genetic differences between them,” the argument is “Genetic differences between groups exist, therefore the groups are races.”

Fish goes on to write that if we take a group of bowlers and a group of golfers then, by chance, there may be genetic differences between them but we wouldn’t call them “golfer races” or “bowler races.” If there were differences in IQ, income and other variables, he continues, we wouldn’t argue that the differences are due to biology, we would attempt argue that the differences are social. (Though I can see behavioral geneticists try to argue that the differences are due to differences in genes between the groups.)

So the reasoning that Jensen uses is clearly fallacious. Though, it is better than Levin’s (1997) and Rushton’s (1997) assumptions that race exists, it still fails since Jensen (1998) is attempting argue that genetic differences between groups make them races. Lynn (2006: 11) uses a similar argument to the one Jensen provides above. (Nevermind Lynn conflating social and biological races in chapter 2 of Race Differences in Intelligence.)

Arguments exist for the existence of race that doesn’t, obviously, assume their existence. The two best ones I’m aware of are by Hardimon (2017) and Spencer (2014, 2019).

Hardimon has four concepts: the racialist race concept (what I take to be the hereditarian position), the minimalist/populationist race concept (they are two separate concepts, but the populationist race concept is the “scientization” of the minimalist race concept) and the socialrace concept. Specifically, Hardimon (2017: 99) defines ‘race’ as:

… a subdivision of Homo sapiens—a group of populations that exhibits a distinctive pattern of genetically transmitted phenotypic characters that corresponds to the group’s geographic ancestry and belongs to a biological line of descent initiated by a geographically separated and reproductively isolated founding population.

Spencer (2014, 2019), on the other hand, grounds his racial ontology in the Census and the OMB—what Spencer calls “the OMB race theory”—or “Blumenbachian partitions.” Take Spencer’s most recent (2019) formulation of his concept:

In this chapter, I have defended a nuanced biological racial realism as an account of how ‘race’ is used in one US race talk. I will call the theory OMB race theory, and the theory makes the following three claims:

(3.7) The set of races in OMB race talk is one meaning of ‘race’ in US race talk.

(3.8) The set of races in OMB race talk is the set of human continental populations.

(3.9) The set of human continental populations is biologically real.

I argued for (3.7) in sections 3.2 and 3.3. Here, I argued that OMB race talk is not only an ordinary race talk in the current United States, but a race talk where the meaning of ‘race’ in the race talk is just the set of races used in the race talk. I argued for (3.8) (a.k.a. ‘the identity thesis’) in sections 3.3 and 3.4. Here, I argued that the thing being referred to in OMB race talk (a.k.a. the meaning of ‘race’ in OMB race talk) is a set of biological populations in humans (Africans, East Asians, Eurasians, Native Americans, and Oceanians), which I’ve dubbed the human continental populations. Finally, I argued for (3.9) in section 3.4. Here, I argued that the set of human continental populations is biologically real because it currently occupies the K = 5 level of human population structure according to contemporary population genetics.

Whether or not one accepts Hardimon’s and Spencer’s arguments for the existence of race is not the point here, however. The point here is that these two philosophers have grounded their belief in the existence of race in a sound philosophical grounding—we cannot, though, say the same things for the hereditarians.

It should also be noted that both Spencer and Hardimon discount hereditarian theory—indeed, Spencer (2014: 1036) writes:

Nothing in Blumenbachian race theory entails that socially important differences exist among US races. This means that the theory does not entail that there are aesthetic, intellectual, or moral differences among US races. Nor does it entail that US races differ in drug metabolizing enzymes or genetic disorders. This is not political correctness either. Rather, the genetic evidence that supports the theory comes from noncoding DNA sequences. Thus, if individuals wish to make claims about one race being superior to another in some respect, they will have to look elsewhere for that evidence.

So, as can be seen, hereditarian ‘reasoning’ on race is not grounded in anything—they just assume that races exist. This stands in stark contrast to theories of race put forth by philosophers of race. Nonhereditarian theories of race exist—and, as I’ve shown, hereditarians don’t define race, nor do they have an argument for the existence of races, they just assume their existence. But, for the hereditarian paradigm to be valid, they must be biologically real. Hardimon and Spencer argue that they are, but hereditarian theories do not have any bearing on their theories of race.

There is the hereditarian ‘reasoning’ on race: either assume its existence sans argument or argue that genetic differences between groups exist so the groups are races. Hereditarians need to posit something like Hardimon or Spencer.

Jews, IQ, Genes, and Culture

1500 words

Jewish IQ is one of the most-talked-about things in the hereditarian sphere. Jews have higher IQs, Cochran, Hardy, and Harpending (2006: 2) argue due to “the unique demography and sociology of Ashkenazim in medieval Europe selected for intelligence.” To IQ-ists, IQ is influenced/caused by genetic factors—while environment accounts for only a small portion.

In The Chosen People: A Study of Jewish Intelligence, Lynn (2011) discusses one explanation for higher Jewish IQ—that of “pushy Jewish mothers” (Marjoribanks, 1972).

“Fourth, other environmentalists such as Majoribanks (1972) have argued that the high intelligence of the Ashkenazi Jews is attributable to the typical “pushy Jewish mother”. In a study carried out in Canada he compared 100 Jewish boys aged 11 years with 100 Protestant white gentile boys and 100 white French Canadians and assessed their mothers for “Press for Achievement”, i.e. the extent to which mothers put pressure on their sons to achieve. He found that the Jewish mothers scored higher on “Press for Achievement” than Protestant mothers by 5 SD units and higher than French Canadian mothers by 8 SD units and argued that this explains the high IQ of the children. But this inference does not follow. There is no general acceptance of the thesis that pushy mothers can raise the IQs of their children. Indeed, the contemporary consensus is that family environmental factors have no long term effect on the intelligence of children (Rowe, 1994).

The inference is a modus ponens:

P1 If p, then q.

P2 p.

C Therefore q.

Let p be “Jewish mothers scored higher on “Press for Achievement” by X SDs” and let q be “then this explains the high IQ of the children.”

So now we have:

Premise 1: If “Jewish mothers scored higher on “Press for Achievement” by X SDs”, then “this explains the high IQ of the children.”

Premise 2: “Jewish mothers scores higher on “Press for Achievement” by X SDs.”

Conclusion: Therefore, “Jewish mothers scoring higher on “Press for Achievement” by X SDs” so “this explains the high IQ of the children.”

Vaughn (2008: 12) notes that an inference is “reasoning from a premise or premises to … conclusions based on those premises.” The conclusion follows from the two premises, so how does the inference not follow?

IQ tests are tests of specific knowledge and skills. It, therefore, follows that, for example, if a “mother is pushy” and being pushy leads to studying more then the IQ of the child can be raised.

Looking at Lynn’s claim that “family environmental factors have no long term effect on the intelligence of children” is puzzling. Rowe relies heavily on twin and adoption studies which have false assumptions underlying them, as noted by Richardson and Norgate (2005), Moore (2006), Joseph (2014), Fosse, Joseph, and Richardson (2015), Joseph et al (2015). The EEA is false so we, therefore, cannot accept the genetic conclusions from twin studies.

Lynn and Kanazawa (2008: 807) argue that their “results clearly support the high intelligence theory of Jewish achievement while at the same time provide no support for the cultural values theory as an explanation for Jewish success.” They are positing “intelligence” as an explanatory concept, though Howe (1988) notes that “intelligence” is “a descriptive measure, not an explanatory concept.” “Intelligence, says Howe (1997: ix) “is … an outcome … not a cause.” More specifically, it is an outcome of development from infancy all the way up to adulthood and being exposed to the items on the test. Lynn has claimed for decades that high intelligence explains Jewish achievement. But whence came intelligence? Intelligence develops throughout the life cycle—from infancy to adolescence to adulthood (Moore, 2014).

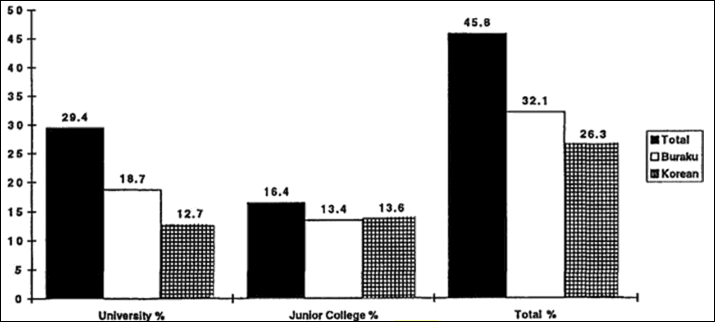

Ogbu and Simon (1998: 164) notes that Jews are “autonomous minorities”—groups with a small number. They note that “Although [Jews, the Amish, and Mormons] may suffer discrimination, they are not totally dominated and oppressed, and their school achievement is no different from the dominant group (Ogbu 1978)” (Ogbu and Simon, 1998: 164). Jews are voluntary minorities, and voluntary minorities, according to Ogbu (2002: 250-251; in Race and Intelligence: Separating Science from Myth) suggests five reasons for good test performance from these types of minorities:

- Their preimmigration experience: Some do well since they were exposed to the items and structure of the tests in their native countries.

- They are cognitively acculturated: They acquired the cognitive skills of the white middle-class when they began to participate in their culture, schools, and economy.

- The history and incentive of motivation: They are motivated to score well on the tests as they have this “preimmigration expectation” in which high test scores are necessary to achieve their goals for why they emigrated along with a “positive frame of reference” in which becoming successful in America is better than becoming successful at home, and the “folk theory of getting ahead in the United States”, that their chance of success is better in the US and the key to success is a good education—which they then equate with high test scores.

So if ‘intelligence’ is a test of specific culturally-specific knowledge and skills, and if certain groups are exposed more to this knowledge, it then follows that certain groups of people are better-prepared for test-taking—specifically IQ tests.

The IQ-ists attempt to argue that differences in IQ are due, largely, to differences in ‘genes for’ IQ, and this explanation is supposed to explain Jewish IQ, and, along with it, Jewish achievement. (See also Gilman, 2008 and Ferguson, 2008 for responses to the just-so storytelling from Cochran, Hardy, and Harpending, 2006.) Lynn, purportedly, is invoking ‘genetic confounding’—he is presupposing that Jews have ‘high IQ genes’ and this is what explains the “pushiness” of Jewish mothers. The Jewish mothers then pass on their “genes for” high IQ—according to Lynn. But the evolutionary accounts (just-so stories) explaining Jewish IQ fail. Ferguson (2008) shows how “there is no good reason to believe that the argument of [Cochran, Hardy, and Harpending, 2006] is likely, or even reasonably possible.” The tall-tale explanations for Jewish IQ, too, fail.

Prinz (2014: 68) notes that Cochran et al have “a seductive story” (aren’t all just-so stories seductive since they are selected to comport with the observation? Smith, 2016), while continuing (pg 71):

The very fact that the Utah researchers use to argue for a genetic difference actually points to a cultural difference between Ashkenazim and other groups. Ashkenazi Jews may have encouraged their children to study maths because it was the only way to get ahead. The emphasis remains widespread today, and it may be the major source of performance on IQ tests. In arguing that Ashkenazim are genetically different, the Utah researchers identify a major cultural difference, and that cultural difference is sufficient to explain the pattern of academic achievement. There is no solid evidence for thinking that the Ashkenazim advantage in IQ tests is genetically, as opposed to culturally, caused.

Nisbett (2008: 146) notes other problems with the theory—most notably Sephardic over-achievement under Islam:

It is also important to the Cochran theory that Sephardic Jews not be terribly accomplished, since they did not pass through the genetic filter of occupations that demanded high intelligence. Contemporary Sephardic Jews in fact do not seem to haave unusally high IQs. But Sephardic Jews under Islam achieved at very high levels. Fifteen percent of all scientists in the period AD 1150-1300 were Jewish—far out of proportion to their presence in the world population, or even the population of the Islamic world—and these scientists were overwhelmingly Sephardic. Cochran and company are left with only a cultural explanation of this Sephardic efflorescence, and it is not congenial to their genetic theory of Jewish intelligence.

Finally, Berg and Belmont (1990: 106) note that “The purpose of the present study was to clarify a possible misinterpretation of the results of Lesser et al’s (1965) influential study that suggested that existence of a “Jewish” pattern of mental abilities. In establishing that Jewish children of different socio-cultural backgrounds display different patterns of mental abilities, which tend to cluster by socio-cultural group, this study confirms Lesser et al’s position that intellectual patterns are, in large part, culturally derived.” Cultural differences exist; cultural differences have an effect on psychological traits; if cultural differences exist and cultural differences have an effect on psychological traits (with culture influencing a population’s beliefs and values) and IQ tests are culturally-/class-specific knowledge tests, then it necessarily follows that IQ differences are cultural/social in nature, not ‘genetic.’

In sum, Lynn’s claim that the inference does not follow is ridiculous. The argument provided is a modus ponens, so the inference does follow. Similarly, Lynn’s claim that “pushy Jewish mothers” don’t explain the high IQs of Jews doesn’t follow. If IQ tests are tests of middle-class knowledge and skills and they are exposed to the structure and items on them, then it follows that being “pushy” with children—that is, getting them to study and whatnot—would explain higher IQs. Lynn’s and Kanazawa’s assertion that “high intelligence is the most promising explanation of Jewish achievement” also fails since intelligence is not an explanatory concept—a cause—it is a descriptive measure that develops across the lifespan.

Knowledge, Culture, Logic, and IQ

5050 words

… what IQ tests actually assess is not some universal scale of cognitive strength but the presence of skills and knowledge structures more likely to be acquired in some groups than in others. (Richardson, 2017: 98)

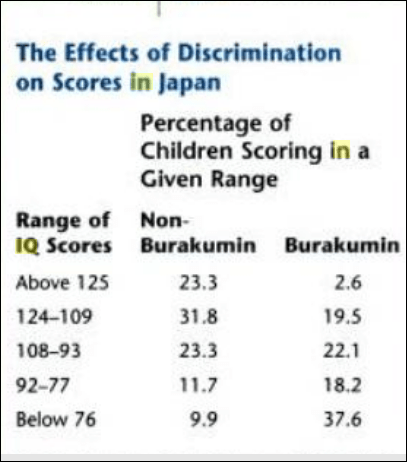

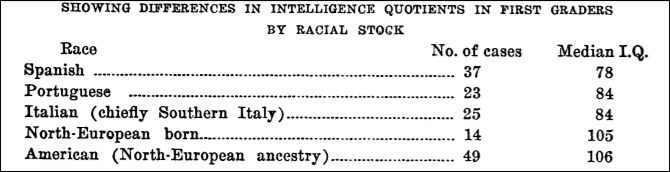

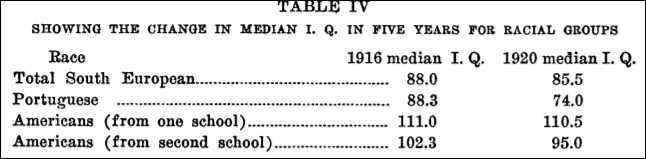

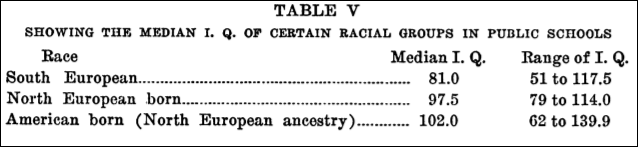

For the past 100 years, the black-white IQ gap has puzzled psychometricians. There are two camps—hereditarians (those who believe that individual and group differences in IQ are due largely to genetics) and environmentalists/interactionists (those who believe that individual and group differences in IQ are largely due to differences in learning, exposure to knowledge, culture and immediate environment).

Knowledge

However, one of the most forceful arguments for the environmentalist (i.e., that the cause for differences in IQ are due to the cultural and social environment; note that an interactionist framework can be used here, too) side is one from Fagan and Holland (2007). They show that half of the questions on IQ tests had no racial bias, whereas other problems on the test were solvable with only a specific type of knowledge – knowledge that is found specifically in the middle class. So if blacks are more likely to be lower class than whites, then what explains lower test scores for blacks is differential exposure to knowledge – specifically, the knowledge to complete the items on the test.

But some hereditarians say otherwise – they claim that since knowledge is easily accessible for everyone, then therefore, everyone who wants to learn something will learn it and thus, the access to information has nothing to do with cultural/social effects.

A hereditarian can, for instance, state that anyone who wants to can learn the types of knowledge that are on IQ tests and that they are widely available everywhere. But racial gaps in IQ stay the same, even though all racial groups have the same access to the specific types of cultural knowledge on IQ tests. Therefore, differences in IQ are not due to differences in one’s immediate environment and what they are exposed to—differences in IQ are due to some innate, genetic differences between blacks and whites. Put into premise and conclusion form, the argument goes something like this:

P1 If racial gaps in IQ were due specifically to differences in knowledge, then anyone who wants to and is able to learn the stuff on the tests can do so for free on the Internet.

P2 Anyone who wants to and is able to learn stuff can do so for free on the Internet.

P3 Blacks score lower than whites on IQ tests, even though they have the same access to information if they would like to seek it out.

C Therefore, differences in IQ between races are due to innate, genetic factors, not any environmental ones.

This argument is strange. One would have to assume that blacks and whites have the same access to knowledge—we know that lower-income people have less access to knowledge in virtue of the environments they live in. For instance, they may have libraries with low funding or bad schools with teachers who do not care enough to teach the students what they need to succeed on these standardized tests (IQ tests, the SAT, etc are all different versions of the same test). (2) One would have to assume that everyone has the same type of motivation to learn what amounts to answers for questions on a test that have no real-world implications. And (3) the type of knowledge that one is exposed to dictates what one can tap into while they are attempting to solve a problem. All three of these reasons can cascade in causing the racial performance in IQ.

Familiarity with the items on the tests influences a faster processing of information, allowing one to correctly identify an answer in a shorter period of time. If we look at IQ tests as tests of middle-class knowledge of skills, and we rightly observe that blacks are lower class than whites who are more likely to be middle class, then it logically follows that the cause of differences in IQ between blacks and whites are cultural – and not genetic – in origin. This paper – and others – solves the century-old debate on racial IQ differences – what accounts for differences in IQ scores is differential exposure to knowledge. Claiming that people have the same type of access to knowledge and, thusly, won’t learn it if they won’t seek it out does not make sense.

Differing experiences lead to differing amounts of knowledge. If differing experiences lead to differing amounts of knowledge, and IQ tests are tests of knowledge—culturally-specific knowledge—then those who are not exposed to the knowledge on the test will score lower than those who are exposed to the knowledge. Therefore, Jensen’s Default Hypothesis is false (Fagan and Holland, 2002). Fagan and Holland (2002) compared blacks and whites on for their knowledge of the meaning of words, which are highly “g”-loaded and shows black-white differences. They review research showing that blacks have lower exposure to words and are therefore unfamiliar with certain words (keep this in mind for the end). They mixed in novel words with previously-known words to see if there was a difference.

Fagan and Holland (2002) picked out random words from the dictionary, then putting them into a sentence to attempt to give the testee some context. They carried out five experiments in all, and each one showed that, when equal opportunity was given to the groups, they were “equal in knowledge” (IQ). So, whites were more likely to know the items more likely to be found on IQ tests. Thus, there were no racial differences between blacks and whites when looked at from an information-processing point of view. Therefore, to expain racial differences in IQ, we must look to differences in the cultural/social environment. Fagan (2000) for instance, states that “Cultures may differ in the types of knowledge their members have but not in how well they process. Cultures may account for racial differences in IQ.”

The results of Fagan and Holland (2002) are completely at-ends with Jensen’s Default Hypothesis—that the 15-point gap in IQ is due to the same environmental and cultural factors that underlie individual differences in the group. However, as Fagan and Holland (2002: 382) show that:

Contrary to what the default hypothesis would predict, however, the within racial group analyses in our study stand in sharp contrast to our between racial group findings. Specifically, individuals within a racial group who differed in general knowledge of word meanings also differed in performance when equal exposure to the information to be tested was provided. Thus, our results suggest that the average difference of 15 IQ points between Blacks and Whites is not due to the same genetic and environmental factors, in the same ratio, that account for differences among individuals within a racial group in IQ.

Exposure to information is critical, in fact. For instance, Ceci (1996) shows that familiarity with words dictates speed of processing to use in identifying the correct answer to the problem. In regard to differences in IQ, Ceci (1996) does not deny the role of biology—indeed, it’s a part of his bio-ecological model of IQ, which is a theory that postulates the development of intelligence as an interaction between biological dispositions and the environment in which those dispositions manifest themselves. Ceci (1996) does note that there are biological constraints on intelligence, but that “… individual differences in biological constraints on specific cognitive abilities are not necessarily (or even probably) directly responsible for producing the individual differences that have been reported in the psychometric literature.” That such potentials, though may be “genetic” in origin, of course, does not license the claim that genetic factors contribute to variance in IQ. “Everyone may possess them to the same degree, and the variance may be due to environment and/or motivations that led to their differential crystallization.” (Ceci, 1996: 171)

Ceci (1996) also further shows that people can differ in intellectual performance due to 3 things: (1) the efficiency of underlying cognitive potentials that are relevant to the cognitive ability in question; (2) the structure of knowledge relevant to the performance; and (3) contextual/motivational factors relevant to crystallize the underlying potentials gained through one’s knowledge. Thus, if one is lacking in the knowledge of the items on the test due to what they learned in school, then the test will be biased against them since they did not learn the relevant information on the tests.

Cahan and Cohen (1989) note that nine-year-olds in fourth grade had higher IQs than nine-year-olds in third grade. This is to be expected, if we take IQ scores as indices of—cultural-specific—knowledge and skills and this is because fourth-graders have been exposed to more information than third-graders. In virtue of being exposed to more information than their same-age cohort in different grades, they then score higher on IQ tests because they are exposed to more information.

Cockroft et al (2015) studied South African and British undergrads on the WAIS-III. They conclude that “the majority of the subtests in the WAIS-III hold cross-cultural biases“, while this is “most evident in tasks which tap crystallized, long-term learning, irrespective of whether the format is verbal or non-verbal” so “This challenges the view that visuo-spatial and non-verbal tests tend to be culturally fairer than verbal ones (Rosselli and Ardila, 2003)”.

IQ tests “simply reflect the different kinds of learning by children from different (sub)cultures: in other words, a measure of learning, not learning ability, and are merely a redescription of the class structure of society, not its causes … it will always be quite impossible to measure such ability with an instrument that depends on learning in one particular culture” (Richardson, 2017: 99-100). This is the logical position to hold: for if IQ tests test class-specific type of knowledge and certain classes are not exposed to said items, then they will score lower. Therefore, since IQ tests are tests of a certain kind of knowledge, IQ tests cannot be “a measure of learning ability” and so, contra Gottfredson, ‘g’ or ‘intelligence’ (IQ test scores) cannot be called “basic learning ability” since we cannot create culture—knowledge—free tests because all human cognizing takes place in a cultural context which it cannot be divorced from.

Since all human cognition takes place through the medium of cultural/psychological tools, the very idea of a culture-free test is, as Cole (1999) notes, ‘a contradiction in terms . . . by its very nature, IQ testing is culture bound’ (p. 646). Individuals are simply more or less prepared for dealing with the cognitive and linguistic structures built in to the particular items. (Richardson, 2002: 293)

Heine (2017: 187) gives some examples of the World War I Alpha Test:

1. The Percheron is a kind of

(a) goat, (b) horse, (c) cow, (d) sheep.

2. The most prominent industry of Gloucester is

(a) fishing, (b) packing, (c) brewing, (d) automobiles.

3. “There’s a reason” is an advertisement for

(a) drink, (b) revolver, (c) flour, (d) cleanser.

4. The Knight engine is used in the

(a) drink, (b) Stearns, (c) Lozier, (d) Pierce Arrow.

5. The Stanchion is used in

(a) fishing, (b) hunting, (c) farming, (d) motoring.

Such test items are similar to what are on modern-day IQ tests. See, for example, Castles (2013: 150) who writes:

One section of the WAIS-III, for example, consists of arithmetic problems that the respondent must solve in his or her head. Others require test-takers to define a series of vocabulary words (many of which would be familiar only to skilled-readers), to answer school-related factual questions (e.g., “Who was the first president of the United States?” or “Who wrote the Canterbury Tales?”), and to recognize and endorse common cultural norms and values (e.g., “What should you do it a sale clerk accidentally gives you too much change?” or “Why does our Constitution call for division of powers?”). True, respondents are also given a few opportunities to solve novel problems (e.g., copying a series of abstract designs with colored blocks). But even these supposedly culture-fair items require an understanding of social conventions, familiarity with objects specific to American culture, and/or experience working with geometric shapes or symbols. [Since this is questions found on the WAIS-III, then go back and read Cockroft et al, 2015 since they used the British version which, of course, is similar.]

If one is not exposed to the structure of the test along with the items and information on them, how, then, can we say that the test is ‘fair’ to other cultural groups (social classes included)? For, if all tests are culture-bound and different groups of people have different cultures, histories, etc, then they will score differently by virtue of what they know. This is why it is ridiculous to state so confidently that IQ tests—however imperfectly—test “intelligence.” They test certain skills and knowledge more likely to be found in certain groups/classes over others—specifically in the dominant group. So what dictates IQ scores is differential access to knowledge (i.e., cultural tools) and how to use such cultural tools (which then become psychological tools.)

Lastly, take an Amazonian people called The Pirah. They have a different counting system than we do in the West called the “one-two-many system, where quantities beyond two are not counted but are simply referred to as “many”” (Gordon, 2005: 496). A Pirah adult was shown an empty can. Then the investigator put six nuts into the can and took five out, one at a time. The investigator then asked the adult if there were any nuts remaining in the can—the man answered that he had no idea. Everett (2005: 622) notes that “Piraha is the only language known without number, numerals, or a concept of counting. It also lacks terms for quantification such as “all,” “each,” “every,” “most,” and “some.””

(hbdchick, quite stupidly, on Twitter wrote “remember when supermisdreavus suggested that the tsimane (who only count to s’thing like two and beyond that it’s “many”) maybe went down an evolutionary pathway in which they *lost* such numbers genes?” Riiiight. Surely the Tsimane “went down an evolutionary pathway in which they *lost* such numbers genes.” This is the idiocy of “HBDers” in action. Of course, I wouldn’t expect them to read the actual literature beyond knowing something basic (Tsimane numbers beyond “two” are known as “many”) and the positing a just-so story for why they don’t count above “two.”

Non-verbal tests

Take a non-verbal test, such as the Bender-Gestalt test. There are nine index cards which have different geometrical designs on them, and the testee needs to copy what he saw before the next card is shown. The testee is then scored on how accurate his recreation of the index card is. Seems culture-fair, no? It’s just shapes and other similar things, how would that be influenced by class and culture? One would, on a cursory basis, claim that such tests have no basis in knowledge structure and exposure and so would rightly be called “culture-free.” While the shapes that come on Ravens tests are novel, the rules governing them are not.

Hoffmann (1966) studied 80 children (20 Kickapoo Indians (KIs), 20 low SES blacks (LSBs), 20 low SES whites (LSWs), and 20 middle-class whites (MCWs)) on the Bender-Gestalt test. The Kickapoo were selected from 5 urban schools; 20 blacks from majority-black elementary schools in Oklahoma City; 20 whites in low SES areas of Oklahoma; and 20 whites from middle-schools in Oklahoma from majority-white schools. All of the children were aged 8-10 years of age and in the third grade, while all had IQs in the range of 90-110. They were matched on a whole slew of different variables. Hoffman (1966: 52) states “that variations in cultural and socio-economic background affect Bender Gestalt reproduction.”

Hoffman (1966: 86) writes that:

since the four groups were shown to exhibit no significant differences in motor, or perceptual discrimination ability it follows that differences among the four groups of boys in Bender Gestalt performance are assignable to interpretative factors. Furthermore, significant differences among the four groups in Bender performance illustrates that the Bender Gestalt test is indeed not a so called “culture-free” test.

Hoffman concluded that MCWs, KIs, LSBs, and LSWs did not differ in copying ability, nor did they differ significantly in discriminating in different phases in the Bender-Gestalt; there also was no bias in figures that had two of the different sexes on them. They did differ in their reproductions of Bender-Gestalt designs, and their differing performance can be, of course, interpreted differently by different people. If we start from the assumption that all IQ tests are culture-bound (Cole, 2004), then living in a different culture from the majority culture will have one score differently by virtue of having differing—culture-specific knowledge and experience. The four groups looked at the test in different ways, too. Thus, the main conclusion is that:

The Bender Gestalt test is not a “culture-free” test. Cultural and socio-economic background appear to significantly affect Bender Gestalt reproduction. (Hoffman, 1966: 88)

Drame and Ferguson (2017) and Dutton et al (2017) also show that there is bias in the Raven’s test in Mali and Sudan. This, of course, is due to the exposure to the types of problems on the items (Richardson, 2002: 291-293). Thus, their cultures do not allow exposure to the items on the test and they will, therefore, score lower in virtue of not being exposed to the items on the test. Richardson (1991) took 10 of the hardest Raven’s items and couched them in familiar terms with familiar, non-geometric, objects. Twenty eleven-year-olds performed way better with the new items than the original ones, even though they used the same exact logic in the problems that Richardson (1991) devised. This, obviously, shows that the Raven is not a “culture-free” measure of inductive and deductive logic.

The Raven is administered in a testing environment, which is a cultural device. They are then handed a paper with black and white figures ordered from left to right. Note that Abel-Kalek and Raven (2006: 171) write that Raven’s items “were transposed to read from right to left following the custom of Arabic writing.” So this is another way that the tests are biased and therefore not “culture-free.”) Richardson (2000: 164) writes that:

For example, one rule simply consists of the addition or subtraction of a figure as we move along a row or down a column; another might consist of substituting elements. My point is that these are emphatically culture-loaded, in the sense that they reflect further information-handling tools for storing and extracting information from the text, from tables of figures, from accounts or timetables, and so on, all of which are more prominent in some cultures and subcultures than others.

Richardson (1991: 83) quotes Keating and Maclean (1987: 243) who argue that tests like the Raven “tap highly formal and specific school skills related to text processing and decontextualized rule application, and are thus the most systematically acculturated tests” (their emphasis). Keating and Maclean (1987: 244) also state that the variation in scores between individuals is due to “the degree of acculturation to the mainstream school skills of Western society” (their emphasis). That’s the thing: all types of testing is biased towards a certain culture in virtue of the kinds of things they are exposed to—not being exposed to the items and structure of the test means that it is in effect biased against certain cultural/social groups.

Davis (2014) studied the Tsimane, a people from Bolivia, on the Raven. Average eleven-year-olds scored 78 percent or more of the questions correct whereas lower-performing individuals answered 47 percent correct. The eleven-year-old Tsimane, though, only answered 31 percent correct. There was another group of Tsimane who went to school and lived in villages—not living in the rainforest like the other group of Tsimane. They ended up scoring 72 percent correct, compared to the unschooled Tsimane who scored only 31 percent correct. “… the cognitive skills of the Tsimane have developed to master the challenges that their environment places on them, and the Raven’s test simply does not tap into those skills. It’s not a reflection of some kind of true universal intelligence; it just reflects how well they can answer those items” (Heine, 2017: 189). Thus, measures of “intelligence” are not an innate skill, but are learned through experience—what we learn from our environments.

Heine (2017: 190) discusses as-of-yet-to-be-published results on the Hadza who are known as “the most cognitively complex foragers on Earth.” So, “the most cognitively complex foragers on Earth” should be pretty “smart”, right? Well, the Hadza were given six-piece jigsaw puzzles to complete—the kinds of puzzles that American four-year-olds do for fun. They had never seen such puzzles before and so were stumped as to how to complete them. Even those who were able to complete them took several minutes to complete them. Is the conclusion then licensed that “Hadza are less smart than four-year-old American children?” No! As that is a specific cultural tool that the Hadza have never seen before and so, their performance mirrored their ignorance to the test.

Logic

The term “logical” comes from the Greek term logos, meaning “reason, idea, or word.” So, “logical reasoning” is based on reason and sound ideas, irrespective of bias and emotion. A simple syllogistic structure could be:

If X, then Y

X

∴ Y

We can substitute terms, too, for instance:

If it rains today, then I must bring an umbrella.

It’s raining today.

∴ I must bring an umbrella.

Richardson (2000: 161) notes how cross-cultural studies show that what is or is not logical thinking is not objective nor simple, but “comes in socially determined forms.” He notes how cross-cultural psychologist Sylvia Scribner showed some syllogisms to Kpelle farmers, which were couched in terms that were familiar to them. One syllogism given to them was:

All Kpelle men are rice farmers

Mr. Smith is not a rice farmer

Is he a Kpelle man? (Richardson, 2002: 162)

The individual then continuously replied that he did not know Mr. Smith, so how could he know whether or not he was a Kpelle man? Another example was:

All people who own a house pay a house tax

Boima does not pay a house tax

Does Boima own a house? (Richardson, 2000: 162)

The answer here was that Boima did not have any money to pay a house tax.

In regard to the first syllogism, Mr. Smith is not a rice farmer so he is not a Kpelle man. Regarding the second, Boima does not pay a house tax, so Boima does not own a house. The individual could give a syllogism that is something like:

All the deductions I can make are about individuals I know.

I do not know Mr. Smith.

Therefore I cannot make a deduction about Mr. Smith. (Richardson, 2000: 162)

They are using what are familiar terms to them, and so, they get the answer right for their culture based on the knowledge that they have. These examples, therefore, show that what can pass for “logical reasoning” is based on the time and place where it is said. The deductions the Kpelle made were perfectly valid, though they were not what the syllogism-designers had in mind. In fact, I would say that there are many—equally valid—ways of answering such syllogisms, and such answers will vary by culture and custom.

The bio-ecological framework, culture, and social class

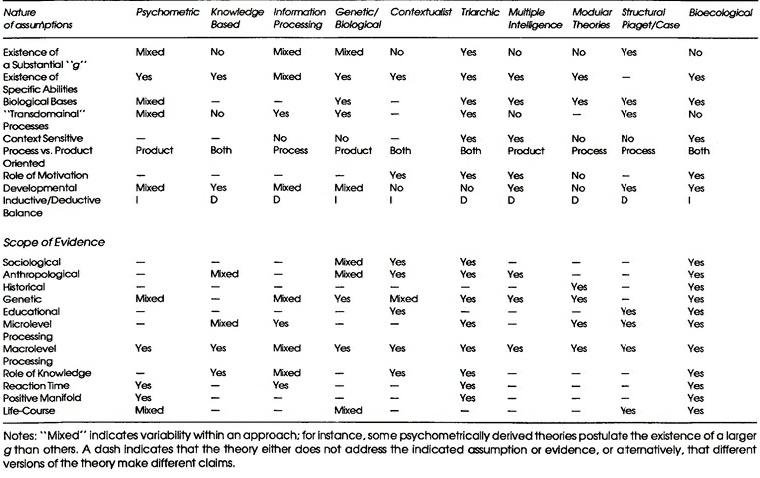

The bio-ecological model of Ceci and Bronfenbrenner is a model of human development that relies on gene and environment interactions. The model is a Vygotskian one—in that learning is a social process where the support from parents, teachers, and all of society play an important role in the ontogeny of higher psychological functioning. (For a good primer on Vygotskian theory, see Vygotsky and the Social Formation of Mind, Wertsch, 1985.) Thus, it is a model of human development that, most hereditarians would say, that “they use too.” Though this is of course, contested by Ceci who compares his bio-ecological framework with other theories (Ceci, 1996: 220, table 10.1):