Race, Medicine, and Epigenetics: How the Social Becomes Biological

2050 words

Race and medicine is a tendentious topic. On one hand, you have people like sociologist Dorothy Roberts (2012) who argues against the use of race in a medical context, whereas philosopher of race Michael Hardimon thinks that we should not be exclusionists about race when it comes to medicine. If there are biological races, and there are salient genetic differences between them, then why should we disregard this when it comes to a medically relevant context? Surely Roberts would agree that we use her socio-political concept of race when it comes to medicine, but not treat them like biological races. Roberts is an anti-realist about biological races, whereas Hardimon is not—he recognizes that there is a minimalist and social aspect to race which are separate concepts.

In his book Rethinking Race: The Case for Deflationary Realism, Hardimon (2017, Chapter 8) discusses race and medicine after discussing and defending his different race concepts. If race is real—whether socially, biologically, or both—then why should we ignore it when it comes to medical contexts? It seems to me that many people would be hurt by such a denial of reality, and that’s what most people want to prevent, and which is the main reason why they deny that races exist, so it seems counterintuitive to me.

Hardimon (2017: 161-162; emphasis his) writes:

If, as seems to be the case, the study of medically relevant genetic variants among races is a legitamate project, then exclusionism about biological race in medical research—the view that there is no place for a biological concept of race in medical research—is false. There is a place for a biological concept of race in the study of medically relevant genetic variants among races. Inclusionism about biological race in medical research is true.

So, we should not be exclusionists (like Roberts), we should be inclusionists (like Hardimon). Sure, some critics would argue that we should be looking at the individual and not their racial or ethnic group. But consider this: Imagine that an individual has something wrong and standard tests do not find out what it is. The doctor then decides that the patient has X disease. They then treat X disease, and then find out that they have Y disease that a certain ethnic group is more likely to have. In this case, accepting the reality of biological races and its usefulness in medical research would have caught this disease earlier and the patient would have gotten the help they needed much, much sooner.

Black women are more likely to die from breast cancer, for example, and racism seems like it can explain a lot of it. They have less access to screening, treatment, care, they receive delays in diagnoses, along with lower-quality treatment than white women. But “implicit racial bias and institutional racism probably play an important role in the explanation of this difficult treatment” (Hardimon, 2017: 166). Furthermore, black women are more than twice as likely to acquire a type of breast cancer called “triple negative” breast cancer (Stark et al, 2010; Howlader et al, 2014; Kohler et al, 2015; DeSantis et al, 2019). Of course, this could be a relevant race-related genetic difference in disease.

We should, of course, use the concepts of socialrace when discussing the medical effects of racism (i.e., psychosocial stress) and the minimalist/populationist race concepts when discussing the medically relevant race-related genetic diseases. Being eliminativist about race doesn’t make sense—since if we deny that race exists at all and do not use the term at all anymore, there would be higher mortality for these “populations.” Thus, we should use both of Hardimon’s terms in regard to medicine and racial differences in health outcomes as both concepts can and will show us how and why diseases are more likely to appear in certain racial groups; we should not be eliminativists/exclusionists about race, we should be inclusionists.

Hardimon discusses how racism can manifest itself as health differences, and how this can have epigenetic effects. He writes (pg 155-156):

As philosopher Shannon Sullivan explains, another way in which racism may be shown to influence health is by causing epigenetic changes in the genotype. It is known that changes in gene expression can have durable and even transgenerational effects on health, passing from parents to their children and their children’s children. This suggests that the biological dimensions of racism can replicate themselves across more than one generation through epigenetic mechanisms. Epigenetics, the scientific study of such changes, explains how the process of transgenerational biological replication of ill health can occur without changes in the underlying DNA sequence.

If such changes to the DNA sequences can be transmitted to the next generation in the developmental system, then that means that the social can—and does—has an effect on our biology and that it can be passed down through subsequent generations. It is simple to explain why this makes sense: for if the developing organism was not plastic, and genes could not change based on what occurs in the environment for the fetus or the organism itself, then how could organisms survive when the environment changes if the “genetic code” of the genome were fixed and not malleable? For example, Jasienska (2009) argues that:

… the low birth weight of contemporary African Americans not only results from the difference in present exposure to lifestyle factors known to affect fetal development but also from conditions experienced during the period of slavery. Slaves had poor nutritional status during all stages of life because of the inadequate dietary intake accompanied by high energetic costs of physical work and infectious diseases. The concept of ‘‘fetal programming’’ suggests that physiology and metabolism including growth and fat accumulation of the developing fetus, and, thus its birth weight, depend on intergenerational signal of environmental quality passed through generations of matrilinear ancestors.

If the environmental quality—i.e., current environmental quality—is “known” by the developing fetus through cues from the mother’s nutrition, stress etc, then a smaller body size may be adaptive in that certain environment and the organism may survive with fewer resources due to smaller body size. In any case, I will discuss this in the future but it was just an example of a possible epigenetic modification on current slaves. I, personally, have noticed that a lot of blacks are really skinny and have really low body fat—who knows, maybe this could be part of the reason why?

This is something that sociologist Maurizio Meloni (2018) calls “the postgenomic body”—the fact that biology is malleable through what occurs in our social lives. So not only is the human brain plastic, but so is the epigenome and microbiome, which is affected by diet and lifestyle—along with what we do and what occurs to us in our social lives. So our social lives, in effect, can become embodied in our epigenome and passed down to subsequent generations. Similar points are also argued by Ulijaszek, Mann, and Elton (2012). (Also see my article Nutrition, Development, Epigenetics, and Physical Plasticity.)So in effect, environments are inherited too, and so, therefore, the environments that we find ourselves in are, in effect, passed down through the generations. Meloni (2018) writes:

On the other hand, by re-embedding the individual within a wider lineage of ancestral experiences and reconfiguring it as a holobiontic assemblage, it may literally dissolve the subject of emancipation. Moreover, the power of biological heredity may be so expanded (as it includes potentially any single ancestral experience) to become stronger than in any previous genetic view. Finally, the several iterations of plasticity that emerge from this genealogy appear so deeply racialized and gendered that it is difficult to quickly turn them into an inherently emancipatory concept. Even as a concept, plasticity has an inertial weight and viscosity that is the task of the genealogist to excavate and bring into view.

Thus, current biological states can be “tagged” and therefore be epigenetically transmitted to future generations. Think about it in this way: if epigenetic tags can be transmitted to the next generation then it would be presumed that that environment—or a similar one—would be what newer generations would be born in. Thus, the plasticity of the organism would help it in life, especially the immediate plasticity of the organism in the womb. Likewise, Kuzawa and Sweet (2008) argue:

that environmentally responsive phenotypic plasticity, in combination with the better-studied acute and chronic effects of social-environmental exposures, provides a more parsimonious explanation than genetics for the persistence of CVD disparities between members of socially imposed racial categories.

Of course, if we look at race as both a biological and social category (i.e., Spencer, 2014), then this is not surprising that differences in disease acquisition can persist “between members of socially imposed racial categories.” Phenotypic plasticity is the big thing here, as noted by many authors who write about epigenetics. If the organism is plastic (if it can be malleable and change depending on external environmental cues), then disease states can—theoretically—be epigenetically passed to future generations. This is just like Jasienska’s (2009, 2013, Chapter 5) argument that the organism—in this case, the fetus—can respond to the environmental quality that it is developing in and, therefore, differences in anatomy and physiology can and do occur based on the plasticity of the organism.

Lastly, Jan Badke, author of Above the Gene, Beyond Biology: Toward a Philosophy of Epigenetics (Baedke, 2018), argues that, since the gene-centered view of biology has been upended (i.e., Jablonka and Lamb, 2005; Noble, 2006, 2011, 2012, 2017) for a postgenomic view (Richardson and Stevens, 2015). Genes are not closed off from the environment; all organisms, including humans, are open systems and so, there are relationships between the environment, developmental system, and the genome which affect the developing organism. Baedke and Delgado (2019) argue that the “colonial shadow … biologicizes as well as racializes social-cultural differences among human groups.” Since every race faces specific life challenges in its environment, therefore, each race shows a “unique social status that is closely linked to its biological status.” Thus, differing environments, such as access to different foods (i.e., the effects of obesifying foods) and discrimination can and are passed down epigenetically. Baedke and Delgado (2019: 9) argue that:

… both racial frameworks nutrition plays a crucial role. It is a key pathway over which sociocultural and environmental difference are embodied as racial difference. Thus, belonging to a particular race means having a particular biosocial status, since races include two poles – a social status (e.g., class, socio-economic status) and a biological status (disease susceptibility) – which are closely interlinked. Against this background, human populations in Mexico become an exemplar of types of bodies that are not only relocated to a destabilizing modernized world in which they suffer from socio-economic deprivation. What is more, they become paradigmatic primitive bodies that are unbalanced, biologically deprived, and sick. In short, in these recent epigenetic studies poor places and lifestyles determine poor bodies, and vice versa.

In sum, accepting the reality of race—both in a minimalist/populationist biological manner and social manner—can and will help us better understand disease acquisition and differing levels of certain diseases between races. Recognizing the minimalist/populationist concepts of race will allow us to discover genetic differences between races that contribute to variation in different diseases—since genes do not alone outright cause diseases (Kampourakis, 2017: 19). Being eliminativist/exclusionist about race does not make sense, and it would cause much more harm than good when it comes to racial disease acquisition and mortality rates.

Furthermore, acknowledging the fact that the social dimensions of race can help us understand how racism manifests itself in biology (for a good intro to this see Sullivan’s (2015) book The Physiology of Racist and Sexist Oppression, for even if the “oppression” is imagined, it can still have very real biological effects that could be passed onto the next generation—and it could particularly affect a developing fetus, too). It seems that there is a good argument that the effects of slavery could have been passed down through the generations manifesting itself in smaller bodies; these effects also could have possibly manifested itself in regard to obesity in Latin America post-colonialism. Gravlee (2009) and Kaplan (2010) also argue that the social, too, manifests itself in biology.

(For further information on how the social can and does become biological see Meloni’s (2019) book Impressionable Biologies: From the Archaeology of Plasticity to the Sociology of Epigenetics, along with Meloni (2014)‘s paper How biology became social, and what it means for social theory. Reading Baedke’s and Meloni’s arguments on plasticity and epigenetics should be required before discussing these concepts.)

Lupus and Race/Ethnicity

1000 words

I’m watching Mystery Diagnosis right now, and I heard the narrator say that lupus is three times more common in African Americans than Caucasian Americans. (The woman was black.) So let’s look into it.

Lupus is a long-term autoimmune disease where the body’s immune system becomes hyperactive and attacks healthy tissue. It can damage any part of the body, skin cells, joints, organs. Many symptoms of lupus exist, like kidney inflammation, swelling, and damage to the blood, heart, joints, and lungs. No cure exists for lupus, though there are ways to minimize inflammation through diet and lifestyle.

Lupus is two to three times more likely to occur in women of color—blacks, Hispanics/Latinos, Native Americans, and others—compared to white Americans. Somers et al (2014) state that lupus affects 1 in 537 black women, “with black patients experiencing earlier age at diagnosis, >2-fold increases in SLE incidence and prevalence, and increased proportions of renal disease and progression to ESRD as compared to white patients.” However, Somers et al (2016) note that medical records may be poor or missing while the reliability of diagnosis is low for non-whites and non-blacks. They also note that race and ethny data in the US is based on self-ID for the parents and child on the birth certificate, but self-ID has almost a perfect relationship with geographic ancestry (i.e., race) (Tang et al, 2005).

Guillermo et al (2017: 7) write that:

Ethnicity is a biological and social construct, including not only genetic ancestry, but also cultural characteristics (language, religion, values, social behaviors, country of origin) yet it is an arbitrary definition [120]. Race is oftentimes used interchangeable with ethnicity but it mainly refers to the biological features of groups of people. Given that there are differences in the clinical characteristics and prognosis among different populations, it is worth evaluating the impact of race/ethnicity in SLE. Genetic ancestry influences the risk for the incidence of SLE; for example, Amerindian ancestry is associated with an increased number of risk alleles for SLE [121], and also with an early age at onset [122], Amerindian and African ancestry are associated with a higher risk for kidney involvement [122,123] and European ancestry with a lower risk [124].

First, let’s look at ref [120], which is McKenzie and Crowcroft (1994), who Guillermo et al (2017) cite as saying that ethnicity is “an arbitrary definition.” They note that some researchers use Blumenbach’s terms (see Spencer, 2014). They claim that modern definitions class Asians as Caucasian or black … what? They state that modern definitions classify Asians as black because “all disadvantaged groups [are] “black populations,”

[since] the experience of racism is paramount.” This is ridiculous on so many levels.

In any case, Southern Europeans are more likely to have a higher risk of renal involvement, and antibody production but along with that a lower risk of discoid rash whereas Western Europeans while Ashkenazi Jews “seem to be protected from neurologic manifestations” (see Richman et al, 2009). Asians and Native Americans in Canada are less likely to have manifestations than Africans; a type of lupus known as cutaneous vasculitis is more common in Native Americans from Canada, while Asians from Canada had a lower rate of serotisis and arthritis compared to Caucasians, Native Americans and African descendants (Peschken et al, 2015). However, Peschken et al (2015) note that while ethnicity was not that strong a predictor of damage accrual, low income was.

Kidney involvement is a major factor in the development of lupus (Bagamant and Fu, 2009), while it is more frequent in “Hispanics”, African-descendants, and Asians. Further, “Hispanics” and blacks are more likely to have end-stage renal failure than whites (Ricardo et al, 2015). When it comes to lupus nephritis—inflammation of the kidneys caused by lupus—“Hispanics” also have a better response to mycophenolate mofetil, which is an immunosuppressive drug that prevents organ rejection (Appel et al, 2009). After the onset of the disease, the disease declines slowly in “Hispanics”, then Africans, and finally fastest in whites. There also seems to be an SES factor in the aetiology of the disease. Sule and Petri (2005) write that “Socioeconomic status can have a major impact on SLE disease manifestations and mortality, independent of ethnicity“, while saying that association with SES is all over the place, with there being no relationship with SES and lupus acquisition.

Vila et al (2003) studied “Hispanics” from Texas and Puerto Rico. They noted that those from Texas accrued more damage than those from Puerto Rico. This is not surprising. “Hispanics” are not a homogenous group (they are a socialrace with no minimalist correlate, they have differing admixture from all over; “Hispanics” can be of any race. Vila et al (2007: 362) note that:

This diversity appears to be areflection of the great variability that exists between these populations with regards to their genetic, environmental and sociodemographic backgrounds.

“Hispanics” from the southeast part of America are different ethnically than those from the southeast.

Blacks and “Hispanics” have a higher rate of mortality than whites, but these differences disappear once SES is accounted for (Ward, Pyun, and Studenski, 1995; Kasitanon, Magder, and Petri, 2006; Fernandez et al, 2007). There could be some genetic differences between races/ethnies that contribute to disease differences between them. But as Kampourakis (2017: 19) notes in his book Making Sense of Genes:

… genes do not alone produce characters or disease but contribute to their variation. This means that genes can account for variation in characters but cannot alone explain their origin.

In sum, there is a wide range of differences between races and ethnies when it comes to lupus. Is the main cause environmental or genetic? Neither, as genes and environment interact to form disease (and any other) phenotypes. So if one at-risk minority group has a low SES, that may be a risk factor. The fact that there are ethnic differences in response to autoimmune drugs when it comes to certain forms of lupus is interesting. The wide range of ethnic differences in the acquisition of the disease is interesting, with Ashkenazi Jews seemingly protected from the disease. In any case, there are racial/ethnic differences in the acquisition of this disease and to better treat those with this disease—and any other—we need to be realists about race, whether it’s biological or social, since there are very real disease and mortality outcomes between them.

What Rushton Got Wrong

1700 words

JP Rushton’s career was pretty much nothing but peddling bullshit. In the beginning of his career, he was a social learning theorist. He published a book Altruism, Socialization, and Society (Rushton, 1980). I bought the book a few years back when I was still a hardcore Rushton defender to see what he wrote about before he started pushing IQ and evolutionary theories about human races and I thought it was pretty good. In any case, Rushton got a lot wrong. So much so, that his career was, in my opinion, wasted peddling bullshit. Rushton was shown to be wrong time and time again on r/K theory and cold winter theory; Rushton was shown to be wrong time and time again on his crime theorizing; and Rushton’s and Jensen’s papers on the causes of the black-white IQ gap rest on a misunderstanding of heritability. In this piece, I will cover those three subjects.

Recently, two new papers have appeared that have a bone to pick with Rushton: One by Flynn (2019) and the other by Cernovsky and Litman (2019). Flynn discusses Rushton’s claims on the method of correlated vectors, his cold winter theory (that Asians and Europeans were subjected to harsher climates which led to higher levels of intelligence and therefore IQ) and his misuse of regression to the mean. He also discussed how the black-white IQ gap is environmental in nature (which is the logical position to hold, since IQ tests are tests of middle-class knowledge and skills (Richardson, 2002) and they are not construct valid).

Cold Winters Theory

Rushton theorized that, due to exposure to harsher environments, that Europeans and East Asians evolved to be more intelligent than Africans who stayed in the, what I assume to be, less harsh environments of Africa (Rushton, 1985). This is Rushton’s “Differential K theory.” Flynn (2019) writes that he “can supply an evolutionary scenario for almost any pattern of current IQ scores.” And of course, one can do that with any evolutionary adaptive hypothesis.

Even Frost (2019) admits that “there is no unified evolutionary theory of human intelligence, other than the general theory of evolution by natural selection.” But since “natural selection” is not a mechanism (Fodor, 2008; Fodor and Piattelli-Palmarini, 2010), then it cannot explain the evolution of intelligence differences, nevermind the fact that, mostly, these claims are pushed by differences in non-construct valid IQ test scores.

In any case, Rushton’s theory is a just-so story.

r/K selection

Judith Anderson (1991) refuted Rushton’s hypothesis on ecological grounds. Rushton asserted that Africans were r-selected whereas Asians and Europeans were more K-selected. Rushton, however, did not even use alpha-selection, which is selection for competitive ability. So r- and K selection is based on density-independence and density-dependence. K-selection is expected to favor genotypes that persist at high densities—increasing K—whereas r-selection is expected to favor genotypes that increase more quickly at low densities—increasing r. Alpha-selection can also occur at high or low population densities but is more likely in high densities. Though alpha-selection “favours genotypes that, owing to their negative effects on others, often reduce the growth rate and the maximum population size” (Anderson, 1991: 52). I further discussed the huge flaws with Rushton’s r/K model here. So Rushton’s theory fails on those grounds, along with many others.

Race

When it came to race, Rushton was a lumper, not a splitter. What I mean by these terms is simple: lumpers lump together Native Americans with East Asians and Pacific Islanders with Africans while splitters split them into further divisions. Why was Rushton a lumper? Because it fit more with his theory, of course. I remember back when I was a Rushton-ist, and I was, too, a lumper, that to explain away the low IQs of Native Americans—and in turn their achievements—was that they still had their intelligence from the cold winters and that’s when they did their achievements. Then, as they spent more time in hotter climates, they became dumber. In any case, there is no justification for lumping Native Americans with East Asians. Looking through Rushton’s book, he gives no justification for his lumping, so I can only assume that it is bias on his part. Now I will justify the claim that splitting is better than lumping. (Rushton also gave no definition of race, and according to Cernovsky and Litman (2019: 54), Rushton “failed to provide any scientific definition of race …”

Race is both a social and biological construct. I can justify the claim that Natives and East Asians are distinct races in one way here: ask both groups if the other is the same race. What do you think the answer will be? Now, onto genetics.

Spencer (2014) discusses the results from Tishkoff et al (2009), saying that when they added 134 ethnic groups to the ones found in the HDGP sample of 52, the K=5 partition clustered Caucasians, Mongoloids, and three distinct sets of Africans. Mongoloids, in this case, being East Asians, Native Americans, and Oceanians. But Tishkoff et al oversampled African ethnic groups. This, though, does not undercut my argument: of course when you oversample ethnic groups you will get the result of Tishkoff et al (2009) and since Africans were oversampled, the populations more genetically similar were grouped into the same cluster, which, of course, does not mean they are the same race.

Census racial discourse is just national racial discourse. The census uses defers to the OMB to define race. How does the OMB define race? The OMB defines “race” as “sets of” populations. Race in US racial discourse designates a set of population groups, thus, race is a particular, not a kind.

I can then invoke Hardimon’s (2017) argument for the existence of minimalist races:

1 There are differences in patterns of visible physical features which correspond to geographic ancestry.

2 These patterns are exhibited between real groups.

3 These groups that exhibit these physical patterns by geographic ancestry satisfy conditions of minimalist race.

C Race exists.

Now we can say:

1 If Native Americans and East Asians are phenotypically distinct, then they are different races.

2 Native Americans and East Asians are phenotypically distinct.

C Therefore Native Americans and East Asians are different races.

Crime

Rushton arbitrarily excluded data that did not fit his theory. How dishonest. Cernovsky and Litman (2019) write:

When Rushton presented crime statistics derived from 2 Interpol Yearbooks as allegedly supporting his thesis that Negroids are more crime inclined than Caucasoids, he arbitrarily excluded disconfirmatory data sets. When all data from the same two Interpol Yearbooks are re-calculated, most of the statistically significant trends in the data are in the direction opposite to Rushton’s beliefs: Negroids had lower crime rates than Caucasoids with respect to sexual offenses, rapes, theft, and violent theft or robbery, with most correlation coefficients exceeding .60. While we do not place much credence in such Interpol statistics as they only reproduce information provided by government officials of different countries, our re-analysis indicated that Rushton excluded data that would discredit his theory.

Further throwing a wrench into Rushton’s assertions is his claim that Mongoloids constitutes both East Asians and Native Americans. Well, Central America has some of the highest crime rates in the world—even higher than in some African countries. What is the ad-hoc justification for explaining away this anomaly if they truly are the same race? If they are the same race, why is the crime rate so much higher in Central America? Surely, Rushton’s defenders would claim something along the lines of recent evolution towards X, Y, and Z. But then I would say, then on what basis are they the same race? No matter what Rushton’s defenders say, they are boxed into a corner.

IQ

Lastly, Rushton and Jensen (2005) argued, on the basis of heritability estimates, and twin studies, that the black-white IQ gap is largely genetic in nature. But there are a few problems. They rely largely on a slew of trans-racial adoption studies, all of which have been called into question (Thomas, 2017). IQ tests, furthermore, are not construct valid (Richardson and Norgate, 2015; Richardson, 2017). Heritability estimates also fail. This is because, in non-controlled environments these stats do not tell us much, if anything (Moore and Shenk, 2016). Likewise, Guo (2000: 299) concurs, writing “it can be argued that the term ‘heritability’, which carries a strong conviction or connotation of something ‘heritable’ in everyday sense, is no longer suitable for use in human genetics and its use should be discontinued.” (For more arguments against heritability, read Behavior Genetics and the Fallacy of Nature vs Nurture.)

Rushton and Jensen (2005) also relied on the use of twin studies, however, all of the assumptions that researchers use to attempt to immunize their arguments from refutation are circular and ad hoc; they also agree that MZs experience more similar environments than DZs, too (Joseph et al, 2014; Joseph, 2016, see a summary here; Richardson, 2017). In any case, the fact that G and E interact means that heritability estimates are, in effect, useless in humans. Farm animals are bred in highly controlled environments; humans are not. Thus, we cannot—and should not—accept the results of twin studies; they cannot tell us whether or not genes are responsible for any behavioral trait.

Conclusion

There was a lot that Rushton got wrong. His cold winters theory is a just-so story; East Asians and Native Americans are not the same race; heritability estimates are not a measure of how much genes have to do with phenotypic variation within or between groups; IQ tests are not construct valid; r/K selection theory was slayed as early as 1991 and then again in 2002 (Graves, 2002); twin studies are not informative when it comes to how much genes influence traits, they only measure environmental similarity; and finally, Rushton omitted data that did not fit his hypothesis on racial differences in crime.

It’s sad to think that one can spend a career—about 25 years—spewing nothing but pseudoscience. One of the only things I agree with him on is that races are real—but when it comes to the nuances, I disagree with him, because there are five races, not three. Rushton got a lot wrong, and I do not know why anyone would defend him, even when these glaring errors are pointed out. (For a good look into Rushton’s lies, see Dutton’s (2018) book J. Philippe Rushton: A Life History Perspective and my mini-review on the book.)

Race and Alien Abductions

1550 words

I was watching the show Ancient Aliens a while back (I don’t believe it, it’s great for a good laugh now and then, though) and I recall them “theorizing” that Asians are aliens—specifically due to the Dropa stones. So I was searching Google for some information on it, and I discovered this article Race, Citizenship, and the Politics of Alien Abduction; Or, Why Aliens do not Abduct Asian Americans (Tromly, 2017).

Tromly argues that alien abductions are a specific cultural—national—phenomenon and that certain groups, mainly Asian Americans, are excluded from these so-called abductions. Surely, most readers are familiar with the most famous of all alien abductions—the case of Betty and Barney Hill (Barney Hill was a black man). One night, they were driving down the road. And all of a sudden, they woke up in their car and many hours had elapsed (a concept known as “missing time“). They then went to a hypnotizer and underwent hypnosis. They then described many experiments that the aliens carried out on them. In any case, I’m not going to discuss the so-called abduction here, but this is one case—one of the most famous—of a minority being abducted.

Tromly argues that the notion of alien visitors elicits collectivity in humans—that, of course, all national, racial, and social differences would be put aside in the event of a hostile alien invasion and we would attempt to quell the alien threat. Think War of the Worlds. Indeed, Stephen Hawking argued that we should not attempt to contact aliens. His reasoning was simple: When Europeans came to the Americas in the late 1400s, with their superior technology, they subjugated the natives. Of course, if aliens from far, far away came to earth, they would be far more technologically superior to us—leaps and bounds ahead of the technological superiority when Europeans and Native Americans are compared. So this type of alien invasion, Tromley argues, would spur humans’ “species-consciousness”

Tromly (2017: 278) writes:

According to this paradigm, abductees are traumatized to the point that nationality becomes irrelevant. Describing the trauma of his own abduction in his bestselling book Communion, Whitley Strieber writes, “I was reduced to raw biological response. It was as if my forebrain had been separated from the rest of my system, and all that remained was a primitive creature, in effect the ape out of which we evolved long ago” (18).

So, Tromly then cites psychiatrist John Mack who argues that abductees are not self-selected and that they come from all walks of life. He is pretty much saying that, to the aliens, there is no one type of person that is more desireable to the aliens and therefore no one group is more worthy of visitation than any other. Further, he is arguing that, whatever differences exist between these diverse people, they are equal in one thing: their visitations by alien visitors.

Tromly (2017: 280) then writes:

Lowe argues that this ideal of political membership comes at the cost of specific individuation: “In being represented as citizen within the political sphere… the subject is ‘split off’ from the unrepresentable histories of situated embodiment that contradict the abstract form of citizenship” (2). These inadmissible “particularities” include “race, national origin, locality, and embodiment [that] remain largely invisible within the political sphere” (2). It is useful to revisit Mack’s presentation of the abduction community in light of Lowe’s observations, because his catalogue of abductees is typical of the discourse in that it defines abductees solely in terms of class and profession—in effect, Mack’s example of the diversity of abductees is underwritten by an assumption of sameness. Because he fails to mention other types of difference on the assumption that they are irrelevant, Mack excludes these differences and, ironically, his demonstration of the diversity of the abductee community becomes subtly exclusionary.

Alien abduction, if you keep up with this kind of thing, is pretty obviously racially exclusive: most abductees are white Americans. Though, of course, believers in alien abductions claim that this accurately reflects the racial demographics of America—with whites being the majority racial group.

Tromly then describes a re-telling of the Betty and Barney Hill saga, where the couple he describes are still an inter-racial couple, but the wife remembers the alien abduction, whereas the husband recalls does not remember it, he recalls the night as normal. This story is written by Asian American writer Peter Ho. So when the wife sees a blue alien light, the husband sees blue police lights—implying that alien abductions and police stops are, in a way, coeval. The wife wants to tell the story—the abduction story—since it can be looked at in a broader national context whereas the husband does not want to—since what he recalls of that night was not a night of alien abduction but a night of being stopped by the police. Eventually, the husband gives in to his wife, who was continuously nagging him to “remember’ the abduction. So he “recalled” one under hypnosis, and a completely different one while he dreamed.

Tromly (2017: 287) writes:

The significance of the Asian American abductee’s absence is shaped, in part, by how abduction in general is understood. Accepting accounts of abduction as true accounts of events that have taken place would require hypothesizing about why aliens might be more interested in some ethnicities than others. To understand accounts of abduction as imagined stories that emerge from anxiety, hysteria, or trauma might suggest that these narratives are not a useful avenue for the expression of the concerns of Asian Americans. … Of course, linguistic barriers may be a reason that a certain segment of the Asian American community cannot participate in the textual spread of the abduction phenomenon. (Many abductees recall repressed memories of abduction after reading texts by Hopkins or Strieber.) However, a more compelling reason for their exclusion is that Asian Americans, or the associations they typically bear in popular discourse, disrupt the logic of the abduction narrative.

Great point! What if the aliens can only telepathically communicate with English-speaking people, therefore they are the only ones that get abucted—and not Asian Americans?

Tellingly, Asianness is sometimes used to mark the otherness of extraterrestrial aliens—Strieber, for example, describes the otherworldly features of an alien with whom he comes in contact through a comparison with “Asian” features: “its eyes are slanted, more than an Oriental’s eyes” (60).9 However, rather than focusing on the possible racial connotations of physical descriptions of aliens, it is more productive to examine the similarities between descriptions of alien characteristics and long-standing Asian American stereotypes. Whether they are conceptualized as a threat to humanity or an advanced and enlightened race, aliens that abduct are almost always described as being deliberate, dispassionate, and, needless to say, technologically adept.

Of course, this is where the observation from Ancient Aliens comes from: popular accounts of the aliens are that they are short, physically weak and frail-looking, and, most notably, have slanted eyes. Asians fit this description, too. So, one can see the parallel here: Asians are technologically adapt, as are the aliens. Asians, too, are looked at as being an enlightened race. This, too, pushes the Asian stereotypes—the “yellow peril” stereotype—where Asians want to come to America and take American resources, and the “model minority”—the claim that Asians are what other minorities should strive to be—because they excel “through technological sophistication, emotionless drive” (Tromly, 2017: 288), while they are extremely productive, what I assume aliens would be like.

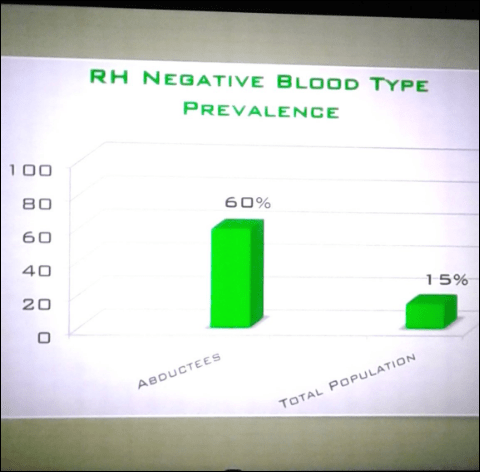

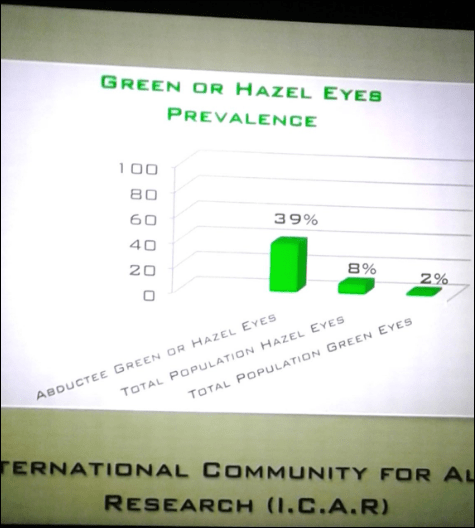

In any case, it seems that alien abductees are actually more likely to be white. I was watching Ancient Aliens last April and they were discussing certain characteristics of abductees—pretty much like Tromly was, without mentioning race. What they mentioned, though, was pretty funny: abductees were more likely to have rH negative blood along with having a higher percentage of green and hazel eyes. I took two pictures of the screen when it came on:

Wow, how interesting, what a disparity. So it seems, that along with not targetting minorities at the same rate as whites, they are targeting a group of people that are more likely to have green eyes and rH negative blood. Then, someone appeared on the screen and then stated that since hazel and green eyes and RH negative blood are due to mutations, that the aliens either created it or they have a special interest in it. They were talking about a “genetic component” to alien abductions. Seems like even being abducted by aliens is “genetic”, too. Wow, what isn’t “genetic” nowadays?

This article wasn’t that serious; I just found this today and read it, and I had a few laughs. While it is interesting that only white Americans seem to be the subjects of alien abductions and the like—and minorities seem to be overlooked—I don’t think it’s anything like Tromly says. Though obviously, I would say that since the aliens are not abducting Asian Americans and aliens look similar to Asians (small bodies, almond-shaped eyes, and weak and frail-looking bodies) and it is hypothesized by Ancient Astronaut “theorists” that aliens are humans from the future, the conclusion is simple to see: these aliens abducting humans are Asians from the future and they’re not abducting Asians because they are looking for different genes and other physiological and anatomic differences, and since they are descended from Asians then why would they abduct them? Checkmate, Ancient Aliens deniers.

The Argument from Simplicity

1200 words

Barnett argues in The Waning of Materialism that for any pair of conscious beings, it is impossible for that pair itself to be conscious. I punch myself and feel pain; You punch yourself and feel pain. But our pair wouldn’t feel a thing. Thus, pairs of people are incapable of experiencing pain. This is what Barnett call’s “The Datum.” He posits six explanations for explaining “The Datum”:

(1) Pairs of people lack a sufficient number of sufficient parts; (2) Pairs of people lack immediate parts of standing in the right sorts of relations to the other and the environment; (3) pairs of people lack the immediate parts of the right kinds of nature; (4) pairs of people are not structures, they are unstructured collections of two parts; (5) some combination of 1-4; and (6) pairs of people are not simple.

Let’s take (1): Imagine that each human on earth is in severe pain, while the collection of people is experiencing pure bliss. This is untenable. Thus, no matter how large, a collection of people cannot be the subject of experience. So pairs of people do not have a sufficient number of immediate parts and thusly do not explain “The Datum.”

Now let’s take (2): Let’s say that scientists shrink you and I down into someone else’s brain, me being the left hemisphere and you being the right hemisphere. Then someone punches the person we have been implanted as their hemispheres; they then react. We then stimulate neurons and the person defends themselves, putting their hands up in defense. We do just what that person’s hemispheres would have done. So we function just like a regular brain. So now you and I have a new relation: is it conscious? You and I may remain conscious, but arethe pair conscious? No. Thus, pairs of people lack the right parts necessary to stand in the right sorts of relations to themselves and the environment and therefore do not explain “The Datum.”

Now let’s take (3): Let’s say I tell you that I have two objects—(a) and (b)—in mind. You, clearly, need more information to conclude that (a) and (b) are conscious, but you don’t need more information to conclude that the pair—comprised of (a) and (b)—is conscious. We know a priori that pairs of things are not conscious; pairs of, say, TVs, rocks, shoes, beds, are not conscious. So, that any pair—(a) and (b)—may be conscious is absurd is not evidence that the two alone are not conscious.

Now let’s take (4): We can know by reflection that the pair comprising (a) and (b) are not conscious. We know a priori that pairs of things are collections while conscious beings are structures. Collections exist iff whenever the comprisal of what makes up the collections exist; a structure of things exists iff the things in question exist in relation to a certain structure. So consider the atoms in the threads in my pillow as a collection and my pillow as a structure. So if we were to disperse the atoms in the thread making up my pillow out into space, the atoms would still exist but my pillow would not. So are pairs of people incapable of having experience because they are not structures? Let’s now return to (2), when you and I were placed in someone’s brain as their hemispheres. So unlike the pair, the system (brain) is a structure and it would cease to exist if you and I were removed from the individual’s brain, though the pair that you and I form would not. However, the system of people is not a candidate for the subject of experience than the pair that constitutes the system. So the idea that pairs of people are incapable of experience since they are not structures does not explain “The Datum.”

Now let’s take (5): Maybe “The Datum” is not explained by (1)-(4). Maybe some combination of the 4 explains “The Datum.” Maybe pairs of people aren’t conscious because it is a collection which results from the existence of two people; maybe a conscious being is a structure comprised of many cells, organs, standing with one another and the environment they are in certain causal dependent relations. So human bodies which are physical structures that are comprised of organs, cells, blood, etc, are conscious; the differences between human bodies are captured in (1)-(4); the four hypotheses do not explain “The Datum” alone; so some combination of (1)-(4) must explain “The Datum.” So let’s go back to (1). If we consider 7 billion people—and not a pair—then we know that no matter the number of people, that collection is not, itself, conscious. Now take (2), but on a larger—societal—level. If everyone in that society has a similar goal and aims for those goals, are they conscious? No; the claim that they are is absurd. Sure, the society functions just as human brain functions, but is that society—itself—conscious? No. Now take (3), but imagine that every neuron in your head was replaced by a mini-man. Thus, if we shift our attention to the number of mini-men in the head to the structure they comprise, it does not make any difference: (1)-(3) does not explain “The Datum.” Finally, let’s take (4). Imagine that your brain was sliced in half and dispersed into vats. Then those hemispheres are halved—while radio transmitters are placed in your hemispheres (preserving communication with the CNS)—and so on and so forth, until each of your neurons sits in its own individual vat. Now imagine that each neuron is paired up with an individual and the neuron gets a break, with the individual then carrying out the function of the specific neuron, Now, what concerns us is whether or not ‘you’ are identical to the scattered parts of what used to comprise ‘you’ and the system that controls your body. Certain times, billions of people operating billions of radio transmitters are operating the system; other days its billions of neurons operating billions of radio transmitters. So these billions of objects which still interact with your nervous system interact with your nervous system just like your brain used to when it was confined to its skull. So whether or not these billions of people that comprise your radio transmitters that control your scattered neurons is irrelevant; what matters is whether the system itself is a subject of experience—and it is not. So no combination of (1)-(4) explains “The Datum.”

Now, finally, let’s take (6): Are pairs of people not qualified from being conscious because they aren’t simple? In all 4 of the hypotheses, composite entities are presented and we ask whether or not the entity may be conscious. Whether or not the entity in question has 2, 100, 100,000, 100,000,000,000 parts is irrelevant. What does matter—however—is whether or not the posited entities presented are a composite. So there is absurdity in the idea that they are identical to a subject of any experience. The only hypotheses that rival this preceding explanation are (1)-(4), but they are inadequate. So simplicity best explains “The Datum.”

So conscious beings must be simple. We are not simple particles, so Barnett’s argument is an argument against materialism. So correlations between our mental states and our brain states do not give reason to identify ourselves with our brains. Therefore we are not our brains.

I am simple. I contain no proper parts (there is no such thing as “half an *I*”). However, my brain contains proper parts. Therefore I am not my brain.