Home » Ethics

Category Archives: Ethics

Strengthening My Argument that Black Americans Deserve Reparations

2350 words

Introduction

In February of last year I constructed an argument that argued since the US government has a history of giving reparations to people who have suffered injustices brought about by the US government (like the Japanese, Natives and victims of sterilization), and since black Americans have suffered injustices brought about by the US government (slavery, Jim Crow, segregation), then it follows that black Americans deserve reparations. But while discussing the argument on Twitter, someone pointed out to me that I can’t derive an ought from an is—which is known as the naturalistic fallacy. Though one can do so if they have an empirical premise and a normative premise which would guarantee a normative conclusion. The normative premise is implicit in the argument. Then, before we derive the conclusion that black Americans deserve reparations, we need a premise that justifies that a rectification of the historical injustices entails that reparations need to be given in order to rectify the historical injustices. I will give the revised argument below, then I will give the argument in formal notation, defend the premises, the validity and soundness of the argument, and show that black Americans indeed deserve reparations from the US government to right the historical wrongs that were inflicted upon them.

(P1) The US government has a history of giving reparations to people who have suffered injustices brought above by them (like the Japanese and Natives).

(P2) The US government has a moral obligation to rectify historical injustices.

(P3) Black Americans have historically suggested from slavery, Jim Crow laws, segregation (systemic along with individual discrimination).

(C) So black Americans deserve reparations from the US government.

Constructing the argument and defending the premises

Variables:

R: Black Americans deserve reparations.

J: Japanese Americans have recreational reparations.

N: Native Americans have received reparations.

O: The US government has a history of giving reparations to people who have suffered injustices.

M: The US government has a moral obligation to rectify historical injustices.

S: Black Americans have historically suffered from slavery, Jim Crow laws, and segregation.

So here’s the argument:

(P1) (J^N) -> O

(P2) M

(P3) S

(C) R

P1 asserts that if Japanese Americans and Native Americans have received reparations, then the US government has a history of giving reparations to people who have suffered injustices—specifically people who have suffered injustices brought about by the US government. This premise is based on historical evidence. Since they have received reparations, then the premise is true. P2 asserts that the US government has a moral obligation to rectify historical injustices. Many believe that the US government has a moral obligation to rectify historical injustices and past harms, and since we have the historical precedence of past harms being rectified by the US government, then there is an argument to be made that black Americans deserve reparations from the US government. P3 asserts that black Americans have suffered injustices brought about by the US government like slavery, Jim Crow, and segregation (which is a combination of individual and systemic racism). Like P1, this premise, too, is supported by historical evidence. Thus, given that the premises are true then the conclusion necessarily follows—black Americans deserve reparations from the US government.

“But wait RR, how is P2 true?” P1 states that J and N have received reparations, so the US government has a history of giving reparations to people it has wronged in the past. There is obviously a moral precedent embedded in P1: If a group of people have suffered injustices, and the US government has provided them reparations, then there is a historical precedent or acknowledgment that rectifying past wrongs is a legitimate action. So P2 builds on this moral principle—it posits that the US government has a moral obligation to rectify historical injustices, and that the obligation arises from the recognition that historical injustices have occurred while having been redressed through reparations for other groups which was indicated in P1.

It can also be put like this: X1 and X2 received reparations because they were wronged. Y was wronged. So Y deserves reparations. Y experienced similar to worse injustices. So due to the precedent set for X1 and X2, Y therefore deserves reparations. I can also further strengthen the argument with a sub-argument for P2 that goes like this:

(P1) If a group has been wronged by a governmental body, then there is a moral obligation for the government to rectify the harm caused.

(P2) If there is a moral obligation for the government to rectify the harm caused, then reparations are necessary to address the wrong.

(C)Thus,if a group has been wronged by a governmental body, then reparations are necessary to rectify the harm caused.

“But wait RR, doesn’t the argument commit the naturalistic fallacy (the is-ought fallacy) since it derives a normative conclusion from empirical premises?” No, it doesn’t. As I argued recently in my article that crime is bad and racism causes crime so racism is morally wrong, if there is an empirical premise and a normative premise, one can derive a normative conclusion and that’s what I did. The argument doesn’t directly derive an ought from an is; it presents the moral premise (the US government has a moral obligation to rectify historical injustices) and factual premises (historical instances of reparations given to other groups and the historical suffering of black Americans), which then allows me to derive the normative conclusion. So the naturalistic fallacy occurs when someone attempts to derive a moral or normative conclusion solely from descriptive or factual premises without any moral premise to bridge the gap. So the moral premise (P2) serves as the bridge between the empirical premises which then allows me to infer the normative conclusion.

So each premise contributes to supporting the conclusion and the logical connections between them guarantee the validity of the argument. Further, not only is the argument valid but it is also sound since it has all true premises. Each premise is well-supported and grounded in historical and ethical considerations which then guarantees the conclusion that black Americans deserve reparations.

I can also put it like this:

(1) If Japanese and Native Americans received reparations, then the US government has a history of giving reparations to people who have suffered injustices.

(2) The US government has a moral obligation to rectify historical injustices.

(3) Since Japanese and Native Americans received reparations, it implies that the US government indeed gives reparations to those who have suffered injustices (conclusion from 1 and 2).

(4) Given that black Americans historically suffered from slavery, Jim Crow laws and segregation, they are included among people who have suffered injustices.

(5) Therefore, based on the established pattern of reparations given by the US government and the moral obligation to rectify historical injustices, black Americans deserve reparations (conclusion from 3 and 4).

For example, Howard-Hassmann (2022) states that “all political entities and all citizens should be willing to offer reparations for activities that would now be considered horrendous crimes, even if they occurred in the far distant past.” While Muhammad (2020: 124-125) states that “apologies are also necessary components of reconciliation, the reality is that monetary compensation is also of vital African nations which participated in the Trans-Atlantic Slave trade have similar legal obligations as European nation states to provide reparations.” I agree with both of these arguments, and they only strengthen my initial argument on reparations for black Americans due to slavery and the US government’s role in the Trade.

Therefore, due to these considerations, reparations are not only a matter of justice but also a response to the persistent legacy of historical racial discrimination in America along with the legacy of slavery. Although there are some arguments that the US should pay Africa reparations for the slave trade, while acknowledging that other groups like Africans themselves and Arabs also participated in the slave trade, (Howard-Hassmann, 2022) and that African nations should pay reparations to black Americans (Muhammad, 2020), it’s not relevant to my argument (although I do agree with both of these arguments) that the US government should pay reparations.

Post-traumatic slave syndrome and intergenerational effects of slavery and Jim Crow

The impact of slavery not only had effects on contemporary birth weights of African Americans (Jasienska, 2009; also see Jasienska’s 2013 book The Fragile Wisdom for an in depth discussion on slavery and it’s intergenerationally-transmitted effects). Furthermore, Jasienska (2013: 117) states that her hypothesis “is that too few generations have elapsed for African Americans living in improved energetic status to counteract the tragic multigenerational effects of nutritional deprivation.” Jasienska (2013: 116) explains:

African Americans suffered nutritional deprivation that lasted much longer, both within each generation and across generations. Even though their caloric intake was higher than that of women during the Dutch famine, slaves’ levels of energy expenditure were extreme. Hard work alone during pregnancy is capable of reducing an infant’s birth weight, regardless of the mother’s caloric intake. Multigenerational exposure to harsh energy-related conditions may change the maternal physiology’s assessment of the quality of environmental conditions. Even when the mother is well nourished herself, as an organism she receives an additional intergenerational signal. The signal may be integrated into her own maternal metabolic processes, and it may cause her organism to follow a specific physiological strategy. This strategy results in the reduced birth weight of her children.

There are a few possible causal physiological mechanisms which may have come into play here that have caused this. For example, epigenetic modifications due to exposure to adverse environmental conditions of slavery like their nutrient deprived environments, the stress they underwent, and the associated inflammatory responses could persist which then influences the intrauterine environment and feral development which ultimately affects birth weight. This then can be exacerbated by post-traumatic slave syndrome (PTSS).

Slavery also led to psychological harm like PTSS—it also makes predictions above violence and health (Halloran, 2018). So quite obviously, there is a body of evidence of the intergenerationally-transmitted effects of slavery and Jim Crow (see Krieger et al, 2013, 2014; Lee et al, 2023). Thus, quite obviously, there are effects of slavery and Jim Crow which have persisted across the generations and—for descendants of both these groups—reparations is a valid way to address these historical wrongs brought about by the US government. This combined with PTSS is yet more evidence that there are grievances which are the outcomes of slavery which led to inequitable outcomes in the modern day, and that reparations can—while not actually fixing the issues (which is up to public health)—can serve as a form of acknowledgement, redress, and restitution for the historical injustices experienced by black American slaves and their descendants.

Conclusion

I have restructured my argument that black Americans deserve reparations by adding a normative premise which bypasses a claim that the argument is guilty of the naturalistic fallacy. I then provided a sub-argument which justifies P2. The sub-argument breaks down the broader concept of moral obligation into specific premises, which makes the argument clearer and more comprehensive. So by explicitly outlining the logical steps in justifying and establishing moral obligation, the sub-argument strengthens the overall argument by addressing a specific objection while clarifying the underlying reasoning. It also highlights the logical connection between moral obligation and the necessity of reparations by showing that if there is a moral imperative to rectify historical injustices, then reparations become a necessary means to fulfill the obligation. This linkage, then, helps to solidify the conclusion that black Americans deserve reparations from the US government.

So the argument for reparations for black Americans rests on a solid foundation of empirical and moral principles. I’ve established that the historical precedent for other marginalized groups establishes a pattern of governmental acknowledgement and rectification of past wrongs. Therefore, this historical context—combined with the moral imperative for the US government to address past systemic injustices—shows the necessity of reparations as a means for redress. So by synthesizing ethical and empirical premises the argument transcends mere appeals for sentiment and political expediency. It represents a genuine recognition of historical injustices—which was shown in P1—and a commitment to address the historical wrongs—historical wrongs that quite clearly have had effects that we see today in America today like low birth weight of black American babies and the effects of PTSS.

Reparations is about the rectification of past wrongs like systemic discrimination against blacks along with attempting to right the wrongs of 400 years of slavery. While descendants of American slavery have inherited psychological, economic, and social burden of their ancestors slavery and oppression along with the injustices of what occurred after (segregation, Jim Crow), there are obviously 2 groups of individuals who deserve such restitution. One group who can trace their ancestry back to American chattel slavery and others who were victims of Jim Crow and segregation.

So providing reparations to black Americans isn’t only a matter of righting past wrongs, it is also a crucial step in addressing the deep-rooted historical injustices that still plague black Americans today. This would then right some wrongs on wealth accumulation as well. One Pew poll shows that 57 percent of black Americans report that their ancestors were enslaved. The Wikipedia article African Americans states that most African Americans are descendants of slavery. Obviously the argument isn’t just about people who self-identify as black Americans, since that implies immigrants would be valid recipients of reparations from the US government. But, if and only if one can show they are descendants of American chattel slavery, and if and only if one identifies as a black American should one be able to be considered for reparations.

So while reparations may not directly address all inequities that derive from slavery and Jim Crow, they can therefore symbolize a commitment to rectifying past wrongs. I have tried, with the renewed argument I made along with the reasoning for my premises, to show that there are indeed effects of slavery and Jim Crow that persist today. Therefore, if one can show they are descendants of either of these two groups then they deserve reparations.

Strategies for Achieving Racial Health Equity: An Argument for When Health Inequalities are Health Inequities

2100 words

Introduction

Health can be defined as “a relative state in which one is able to function well physically, mentally, socially, and spiritually to express the full range of one’s unique potentialities within the environment in which one lives” (Svalastog et al, 2017). Health, clearly, is a multi-dimensional concept (Barr, 2014). Since there are many kinds of referents to the word “health”, it is therefore essential to understand and consider the context and perspective of each person and group when discussing health-related issues and also while implementing healthcare policies and practices.

Inequality exists everywhere on earth and it manifests in numerous forms like in income, health, education, and healthcare access. So the existence of inequality is undeniable, since we can see it with our own eyes, but understanding the mechanisms that lead to inequality should be multifaceted. Central to the understanding of inequality is the relationship between inequality, unfairness and the role of empirical investigations in uncovering not only the implications for societal outcomes, but also in discerning what is an inequity (which is a kind of inequality that is avoidable, unfair and unjust). According to Braveman, (2003: 182):

Health inequities are disparities in health or its social determinants that favour the social groups that were already more advantaged. Inequity does not refer generically to just any inequalities between any population groups, but very specifically to disparities between groups of people categorized a priori according to some important features of their underlying social position.

Talking about health is the best way to understand what inequity actually is. The issue is, true equality of health is impossible, but what is possible is addressing the actual social determinants of health (SDoH). What is also important is understanding what equity is and what equity isn’t, as I have argued in the past. Grifters like James Lindsay and Chris Rufo (along with well-meaning but still wrong institutions) believe that equity is ensuring equal outcomes. This is incorrect. What equity means—in the health sphere—is when “the opportunity to ‘attain their full health potential’ and no one is ‘disadvantaged from achieving this potential because of their social position or other socially determined circumstance’” (Braveman, quoted by the CDC).Therefore, health equity is when everyone has the chance to reach their fill potential, unabated by social determinants. Social conditions and policies strongly influence the health of both individuals and groups and it’s the result of unequal distribution of resources and opportunities. Empirical investigation is pivotal in understanding if a certain inequality is an inequity. And although inequities are a kind of inequality, “inequality” and “inequity” are conceptually distinct (Braveman, 2003).

In this article I will discuss the SDoH, give my argument that we can identify inequity (a kind of inequality) through empirical investigations (meaning that they are avoidable, unfair and unjust). I will then pivot to a real-world example of my argument—that of low birth weight in black American newborns and argue that racism and historical injustices can explain that since non-American black women have children with higher mean birth weights. I will then discuss how blacks who have doctors of of the same race report better care and have higher life expectancies. I will then discuss what can be done about this—and the answer is to educate people on genetic essentialism which leads to racism and racist attitudes.

On SDoH

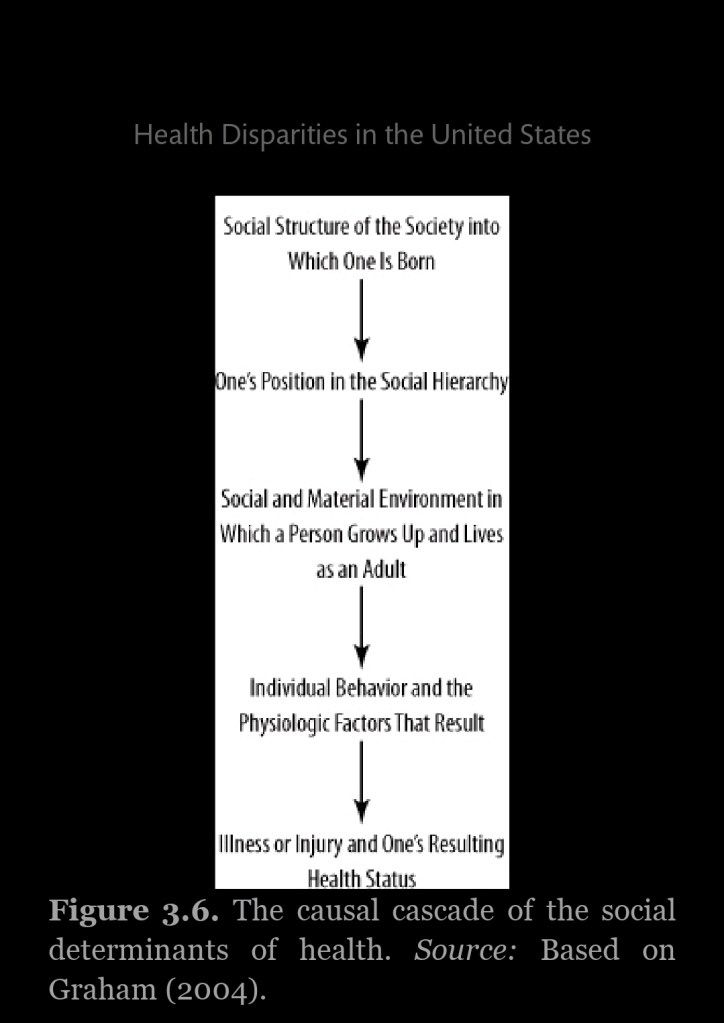

SDoH include the lack of education, racism, lack of access to health care and poverty. Barr (2011: 64) had a helpful flow chart to understand this issue.

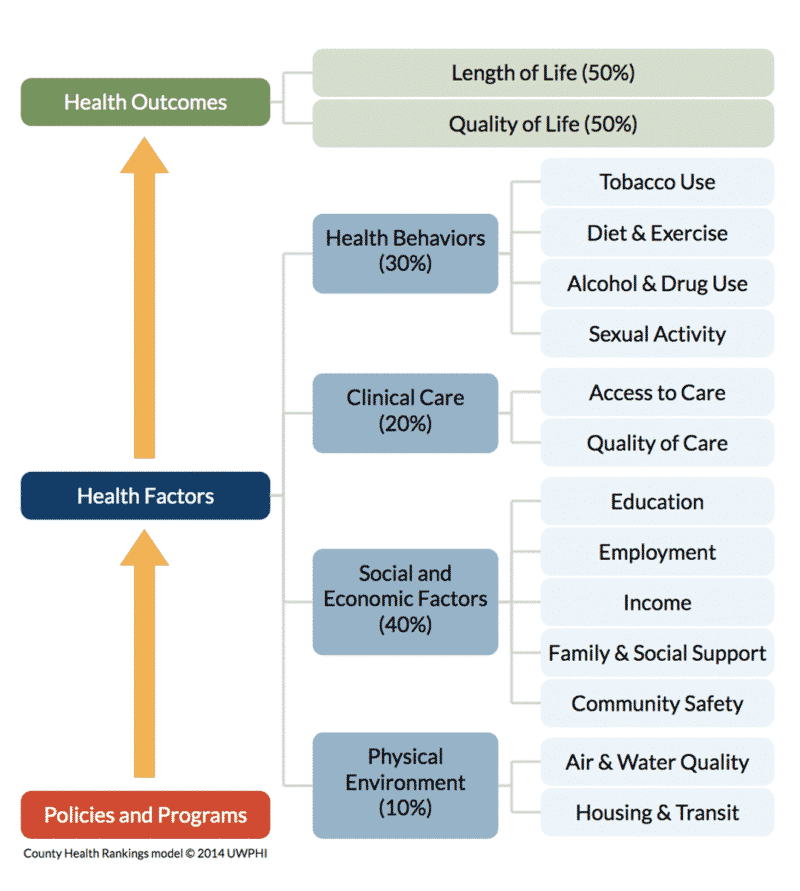

So when it comes to variation in health outcomes, we know that only 20 percent can be attributed to access to medical care, while a whooping 80 percent is attributable to the SDoH:

(Ratcliffe, 2017 also states that about 20 percent of the health of nation is attributed to medical care, 5 percent the result of biology and genes, 20 percent the result of individual action, and 50 percent due to the SDoH.)

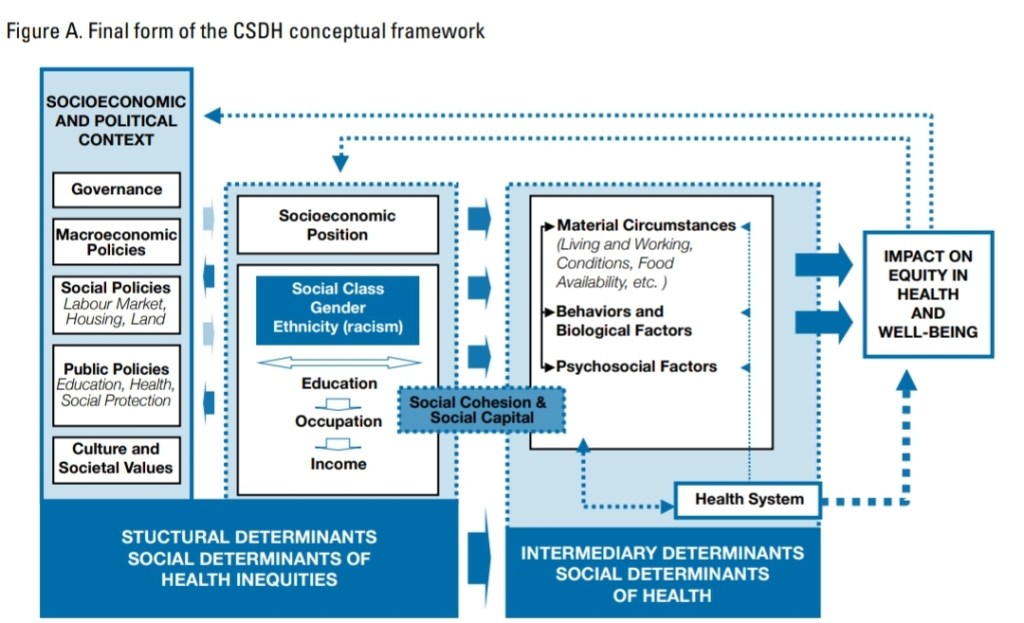

The WHO (2010) also has a Commission on the Social Determinants of Health (CSDH) with a conceptual framework:

This is staggering. For if the social determinants of health are causal for health outcomes, then it comes down to how society is structured along with how we treat certain people and groups. This also could come down to environmental racism—which is the disproportionate exposure of minority groups to environmental hazards. One pertinent example is lead in paint uses in houses in the 80s, where groups actually used blacks as a kind of experiment in seeing the effects of lead. The issue was further exacerbated by Big Lead in trying to argue that the families had a “history of low intelligence” and that it couldn’t be proven that lead had the damaging effects on the children. Not only does environmental racism cause negative health effects, but so does individual racism which is known to have a negative effect on black women. (Racism and stereotypes which lead to self-fulfilling prophecies also cause the black-white crime gap.)

So empirical research—grounded in data and evidence—can help us in understanding whether a given inequality is an inequity. Certain disparities could reflect historical disadvantages which then perpetuate cycles of disadvantage which then reinforce existing power structures and further continue to marginalize certain communities.

The argument

I have constructed an argument that shows what I am talking about:

UO: Unequal outcome

I: Inequality

A: Avoidable

F: Unfair

J: Unjust

E: Empirical investigation

I involves A, F, J. E may reveal instances where I leads to UO and I is associated with F, J, and A.

Premise 1: E -> (A^F^J)

Premise 2: I -> (A^F^J)

Conclusion: E -> ((I -> UO) ^ (A^F^J))

(P1) If empirical investigations (E) reveal instances where avoidable factors (A), unfairness (F) and injustice (J) are present, and (P2) if inequality (I) leads to conditions involving avoidability (A), unfairness (F) and injustice (J), then (Conclusion) empirical investigations (E) could reveal instances where inequality leads to unequal outcomes (UO), and whether or not they are avoidable (A), unfair (F) or unjust (J). Effectively, since inequities are a kind of inequality, then this can identify inequities where they are, and then we can work to fix them.

For instance, birth weight has decreased recently and the effect is more pronounced for black women (Catov et al, 2016) and racism could as well be a culprit (Collins Jr., et al, 2004). There is also evidence that structural racism in the workplace can and has attributed to this (Chantarat et al, 2022). It’s quite clear that racism can explain birth outcome disparities (Dominguez et al, 2010; Alhusen et al, 2016; Dreyer, 2021). Not only does racism contribute to adverse birth outcomes but so too do factors related to environmental racism (Burris and Hacker, 2018). This also has a historical precedent: slavery (Jasienska, 2009). Hereditarians may try to argue that (as always) this difference has a genetic basis. But we know that African women born in Africa are heavier than African American women; black women born in Africa have children with higher mean birth weights than African American women (David and Collins, 1997). Cabral et al (1991) also found the same—non-American black women birthed children that weighed 135 more grams than American black women. Thus, the difference isn’t genetic in nature—it is environmentally caused and it partly stems from slavery. Clearly this discussion shows that my argument has a real-world basis.

How do we reverse these inequities?

Clearly, racism has societal consequences not only for crime and mental illness, but also low birth weight in black American women. The difference can’t be genetic in nature, so it’s obviously environmental/social in nature due to racism, environmental racism. So how can we alleviate this? There are a few ways.

We can improve access to pre-natal care. By ensuring equitable access to pre-natal care, and by expanding Medicaid coverage, we can the begin to address the issue of low black birth weight. We know that when black newborns are cared for by black doctors, they have a better survival rate (Greenwood et al, 2020). We also have an RCT showing that black doctors could reduce the black-white cardiovascular mortality rate by 19 percent (Alsan, Garrick, and Grasiani, 2019). We also know that a higher percentage of black doctors leads to lower mortality rate and better life expectancy (Peek, 2023; Snyder et al, 2023). This isn’t a new finding—we’ve known this since the 90s (Komaramy et al, 1996; Saha et al, 1999). We also know that people who have same-race doctors are more likely to accept much-needed preventative care (LaVeist, Nuru-Jeter, and Jones, 2003). This could then lead to less systemic bias in healthcare, since we know that some of the difference is systemic in nature (Reschovsky and O’Malley 2008: 229, 230). We also know that bias, stereotyping, and prejudice also play a part (Smedley et al, 2003). Such stereotypes are also sometimes unconscious (Williams and Rucker, 2000). The medical system contributes to said disparities (Bird and Clinton, 2001). Blacks who perceived more racism in healthcare felt more comfortable with a black doctor (Chen et al, 2005)—minorities also trust the healthcare system less than whites (Boulware et al, 2003). Lastly, black and white doctors agree that race is a medically relevant data point, but they don’t agree on why (Bonham et al, 2009).

We know that systemic and structural racism exists and that it impacts health outcomes (Braveman et al, 2022). Some may say that systemic and structural racism don’t exist, but this claim is clearly false. They are “are forms of racism that are pervasively and deeply embedded in and throughout systems, laws, written or unwritten policies, entrenched practices, and established beliefs and attitudes that produce, condone, and perpetuate widespread unfair treatment of people of color. They reflect both ongoing and historical injustices” (Braveman et al, 2022). Perhaps the most important way that systemic racism can harm health is through placing people at an economic disadvantage and stress. Environmental racism then compounds this, and then unfair treatment then leads to higher levels of stress which then leads to negative health outcomes.

Lastly a key issue here is the prevalence of racism. We know that it has a slew of negative health effects and that it affects the incidence of the black-white crime gap. But what can be done to alleviate racist attitudes?

Since many racist ideas have a genetically essentialist tilt, then we can use education to ameliorate racist attitudes (Donovan, 2022). We also know that racial essentialist attitudes are related to the belief that evolution has an intentional tilt and that it’s negatively correlated with biology grades (Donovan, 2015). Much of Donovan’s work shows that education can ameliorate racist attitudes which are due to genetic essentialism. We also know that such essentialist thinking is related to misconceptions about heredity and evolution and is correlated with low grades at the end of the semester in beginner biology course (Donovan, 2016). Thus, by providing accurate and understandable education on race, genetics, and evolution, people may be less likely to hold racial essentialist attitudes and more likely to reject racist ideologies. So there are actionable things we can do to combat racism which leads to crime and negative health outcomes for minority groups.

Conclusion

The SDoH play a pivotal role in shaping the health outcomes while perpetuating health inequities. We can, through empirical investigations, ascertain when an inequality is avoidable, unfair and unjust (meaning, when it is an inequity). We can then understand how historical injustices like racism impact marginalized communities which then contribute to negative health outcomes like low birth weight of black American babies. We know that it’s not a genetic difference since non-American black women have children with higher mean birth weights than black American women, and this suggests thar historical injustices and racism are a cause (as Jasienska argues). Further, studies show that when black patients have black doctors, they report better care and have higher life expectancies. Research has also shown that education can play a role in ameliorating genetic essentialist and racist attitudes which then, as I’ve shown, lead to negative health outcomes. The argument I’ve made here has a real-world basis in the case of low birth weight of black American babies.

In sum, committing to social and racial justice can help to change these inequities, and for that, we will have a better and more inclusive society where people’s negative health outcomes aren’t caused by social goings-on. To achieve racial health equity, we must address the avoidable, unfair and unjust factors that contribute to these inequities.

An Argument For and Against Germline Editing

1200 words

In the past few weeks, talks of genetic modification have increased in the news cycle. Questions of whether or not to edit the genes of future people constantly arise. Should we edit genes and or the germline? If we edit the germline, what types of problems would occur? Is it moral to edit the germline of future people (babes are included in this as well) when they have no say? Is it moral to edit the genes of a baby that cannot consent to such editing? I will present one argument for and against editing the germline. This is a really big debate in current contemporary discourse; the argument for editing the germline rests on wanting the best for future people (which of course include our children) while the argument against editing the germline rests on the fact that said future people cannot consent to said germline editing so we should not edit the germline.

An argument for editing the germline

Germline editing is editing the germline in such a way that said edit is heritable—the modification to the germline is then acquired by the next generation of progeny. The rationale for editing the germline could be very simple:

Parents want what’s best for their children; since parents want what’s best for their children, then parents should edit their germline to rid their children of any disease and/or make them the best person they can possibly be, as is the job of all parents; therefore parents should edit the germline so said heritable changes can pass to the next generations since parents want what’s best for their children.

One may say that a babe has no choice in being born, naturally or artificially, and so since parents are able to choose the modifications, then this does consider the babe’s rights as a (future) person/human since it is, in theory, giving the babe the best possible chance at life with little, to no, diseases (that are noticed at conception). Parents can use new, up-and-coming genetic technology to attempt to give their child a head-start in life. They can edit their own germlines, and so, each change done to their germline would pass on to future progeny.

An argument against germline editing

Ethicist Walter Glannon articulates two great arguments against germline editing in his book Genes and Future People: Philosophical Issues in Human Genetics (2002). Glannon (2002: 89-90) writes:

Among other things, however, germ-line genetic alteration may not be desireable from an evolutionary perspective. Some genetic mutations are necessary for species to adapt to changing environmental conditions, and some genetic disorders involve alleles that confer a survival advantage on certain populations.

[…]

This raises the risk of whether or not we have a duty to prevent passing on altered genes with potentially harmful consequences to people who will exist in the distant future. It may recommend avoiding germ-line genetic manipulation altogether, which is supported by two related points. First, people existing in the future may be adversely affected by the consequences of a practice to which they did not consent. Second, because of the complex way in which genes interact, it would be difficult to weigh the probable health benefits of people in the present and near duture generations against the probable health burdens to people in the distant future. Because their interest in, and right to, not being harmed have just as much moral weight as those of the people who already exist or will exist in the near future, we would be well-advised to err on the side of caution. Indded, we would be morally obligated to do so, on the grounds of nonmaleficence. This would mean prohibiting germ-line genetic manipulation, or at least postponing it until further research can provide a more favorable assessment of its safety and efficacy.

I largely agree with Glannon here; though I will take his argument a step further: since future people literally cannot consent to germline genetic modificaitons then we should not edit our germline since we would be passing on the heritable changes to our descendants who did not ask for such changes.

The argument against germline editing is very simple:

(1) People should have a choice in whether or not their genes are modified.

(2) Since people should have a choice in whether or not their genes are modified, they then should be able to say “yes” or “no” to the modifications; though they cannot consent since they are not present to consent to the germline editing they will acquire in the future since they are not alive yet.

(3) Therefore we should not modify the germline without consent from future people, meaning that we should not edit the germline since there is a strong moral imperative to not do so since the future people in question cannot consent to the editing.

This argument against germline editing is a very strong moral argument: if one cannot consent to something, then that something should not be done. Future people cannot consent to germline editing. Therefore we should not edit the germline.

Another thing to think about is that if parents can edit the germline and genes of their children (future people), then it can be said that they would be more like “commodities”, like a handbag or whatnot, since they can make choices of what type of handbag they have, they would then make choices on what type of kid to have.

Hildt (2016) writes:

It is questionable whether there would be broader justifiable medical uses for germline interventions, especially in view of the availability of genetic testing and pre-implantation genetic diagnosis.

Gene editing can give us “designer babies” (though my argument presented above also is an argument against “designer babies” since they are future people, too); it can also put an end to many diseases that plague our society. However, there are many things we need to think about—both ethically/morally and empirically—before we even begin to think about editing our germline cells.

Conclusion

So, on the basis of (1) future people not being able to consent to said germline modifications and (2) us not knowing the future consequences of said germline editing, then we should not edit the germline. We, in fact, have a moral imperative to not do so since they cannot consent. The argument “for” germline editing, in my opinion, do not override the argument “against” germline editing. I am aware that most people would say “Who cares?” in regard to the arguments for or against germline modification, because people would “Just do it anyway.” Though, if there are laws against the editing of the germline, then germline editing cannot (should not) go through. Just because we *can* do something does not mean that we *should* do it.

We should not modify the germline because future people cannot consent to the changes. The moral argument provided here against germline editing is sound; the argument is a very strong moral one and since it is sound we should accept the argument’s conclusion that: “we should not modify the germline without consent from future people, meaning that we should not edit the germline since there is a strong moral imperative to not do so since the future people in question cannot consent to the editing.“

An Argument For and Against Abortion

1350 words

Abortion is a touchy subject for many people. There are many different arguments for and against abortion, including, but not limited to, the woman’s right to do what she wants with her body on the pro-abortion side, to the right of a fetus to live a good life if there is little chance of the fetus developing a serious disease. In this article, I will provide two arguments: one for and one against abortion. The abortion debate is an ethical, not scientific, one, and so, we must use argumentation to see the best way to move forward in this debate.

An argument for abortion

Michael Tooley, in his paper Abortion and Infanticide, provides an argument not only for the abortion of fetuses, but the killing of infants and animals since they cannot conceive of continuing their selves. He argues that an organism only has a right o life of they can conceive of that right to life. His conclusion is that it should be morally permissible to end a baby’s life shortly after birth since it cannot conceive of wanting to live. The conclusion of the argument also includes—quite controversially, in fact—young infants and (nonhuman) animals. Ben Saunders articulates Tooley’s argument in Just the Arguments: 100 of the Most Important Arguments in Western Philosophy (2011: 284-286):

P1. If A has a morally serious right to X, then A must be able to want X.

P2. If A is able to want X, then A must be able to conceive if X.

C1. If A has a morally serious right to X, then A must be able to conceive of X (hypothetical syllogism, P1, P2).

P3. Fetuses, young infants, and animals cannot conceive of their continuing as subjects of mental states.

C2. Fetuses, young infants, and animals cannot want their continuance as subjects of mental states (modus tollens, P2, P3).

C3. Fetuses, young infants, and animals do not have morally serious rights to continue as subjects of mental states (modus tollens, P1, C2).

P4. If something does not have a morally serious right to life, then it is not morally wrong to kill it painlessly.

C4. It is not wrong to kill fetuses, young infants, or animals painlessly (modus ponens, C3, P4).

Of course, most people would seriously disagree with C4, since a babe’s life is one of the most precious things in the world— the protection of said babes is how we continue our species. However, the argument is deductively valid, and so one must show which premise is wrong and why. This argument—along with the one that will be presented below against abortion (of healthy fetuses)—is very strong. Thus, if a woman so pleases (along with her autonomy), she can choose to abort her fetus since it is not wrong to kill a fetus painlessly. (I am not aware if fetuses can feel pain or not, however. If they can, then the conclusion of this argument does not hold.)

Tooley’s argument regarding the killing of infants is similar to an argument made by Gibiulini and Minerva (2013) who argue that since fetuses and newborns don’t have the same moral status as actual persons, fetuses and infants can eventually become persons, and since adoption is not always in the best interests 9f people, then “‘after-birth abortion’ (killing a newborn) should be permissible in all the cases where abortion is, including cases where the newborn is not disabled” (Giubilini and Minerva, 2013).

An argument against abortion

One strong argument against abortion exists: Marquis’ (1989) argument in his paper Why Abortion Is Immoral. Women may want an abortion for many reasons: such as not wanting to carry a babe to term, to finding out that the babe has a serious genetic disorder. Though, what matters to this argument is not the latter, but the former: the mother wanting an abortion of a healthy fetus. Marquis’ argument is simple: killing is wrong; killing is wrong since killing ends one’s life, and ending one’s life means they won’t experience anything anymore, they won’t be happy anymore, they won’t be able to accomplish things, and this is one of the greatest losses that can be suffered; abortions of a healthy fetus cause the loss of experiences, activities, and enjoyment to the fetus; thus, the abortion of a healthy fetus is not only ethically wrong, but seriously wrong. Marquis’ (1989) argument is put succinctly by Leslie Burkholder in the book Just the Arguments: 100 of the Most Important Arguments in Western Philosophy (2011: 282-283):

P1. Killing this particular adult human being or child would be seriously wrong.

P2. What makes it so wrong is that it causes the loss of this individual’s future experiences, activities, projects, and enjoyments, and this loss is one of the greatest losses that can be suffered.

C1. Killing this adult human being or child would be seriously wrong, and what makes it so wrong is that it causes the loss of this individual’s future experiences, activities, projects, and enjoyments, and this loss is one of the greatest losses that can be suffered (conjunction, P1, P2).

P3. If killing this particular adult human being or child would be seriously wrong and what makes it so wrong is that it causes the loss of all this individual’s experiences, activities, projects, and enjoyments, and this loss is one of the greatest losses that can be suffered, then anything that causes to any individual the loss of all future experiences, activities, projects, and enjoyments is seriously wrong.

C2. Anything that causes to any individual the loss of all future experiences, activities, projects, and enjoyments is seriously wrong (modus ponens, C1, P3).

P4. All aborting of any healthy fetus would cause the loss to that individual of all its future experiences, activities, projects, and enjoyments.

C3. If A causes to individual F the loss of all future experiences, activities, projects, and enjoyments, then A is seriously wrong (particular instantiation, C2).

C4. If A is an abortion of healthy fetus F, then A causes to individual F the loss of all future experiences, activities, projects, and enjoyments (particular instantiation, P4).

C5. If A is an abortion of a healthy fetus F, then A is seriously wrong (hypothetical syllogism, C3, C4).

C6. All aborting of any healthy fetus is seriously wrong (universal generalization, C5).

In this case, the argument is about abortion in regard to healthy fetuses. This argument, like the one for abortion, is also deductively valid. (Arguments for and against the abortion of unhealthy fetuses will be covered in the future.) Thus, if a fetus is healthy then it should not be aborted since doing so would cause the individual to lose their future experiences, enjoyments, activities, and projects. Thus, the abortion of a healthy fetus is seriously and morally wrong. This argument clearly establishes the fetuses’ right to life if it is healthy.

Conclusion

Both of these arguments for and against abortion are strong; on the “for” side, we have the apparent facts that fetuses, infants, and (nonhuman) animals cannot want their continuance of their mental states since they cannot conceive of their continuance and want of mental states, so if they cannot want their continuance of their mental states they do not have a morally serious right to life and it is, therefore, morally right to kill them painlessly. On the “against” side, we have the facts that aborting healthy fetuses will cause the loss of all future experiences, enjoyments, activities, and projects, and so, the abortion of these healthy fetuses is both seriously and morally wrong.

I will cover these types of arguments—and more—in the future. However, if one is against genetic modification, embryo selection, preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) and ‘eugenics’, then one must, logically, be against the abortion of healthy fetuses as well. These two arguments, of course, have implications for any looming eugenic policies as well, which I will cover in the future.

(I, personally, lean toward the “against” side in this debate; though, of course, the argument presented in this article on the “for” side is strong as well.)