2100 words

Introduction

Health can be defined as “a relative state in which one is able to function well physically, mentally, socially, and spiritually to express the full range of one’s unique potentialities within the environment in which one lives” (Svalastog et al, 2017). Health, clearly, is a multi-dimensional concept (Barr, 2014). Since there are many kinds of referents to the word “health”, it is therefore essential to understand and consider the context and perspective of each person and group when discussing health-related issues and also while implementing healthcare policies and practices.

Inequality exists everywhere on earth and it manifests in numerous forms like in income, health, education, and healthcare access. So the existence of inequality is undeniable, since we can see it with our own eyes, but understanding the mechanisms that lead to inequality should be multifaceted. Central to the understanding of inequality is the relationship between inequality, unfairness and the role of empirical investigations in uncovering not only the implications for societal outcomes, but also in discerning what is an inequity (which is a kind of inequality that is avoidable, unfair and unjust). According to Braveman, (2003: 182):

Health inequities are disparities in health or its social determinants that favour the social groups that were already more advantaged. Inequity does not refer generically to just any inequalities between any population groups, but very specifically to disparities between groups of people categorized a priori according to some important features of their underlying social position.

Talking about health is the best way to understand what inequity actually is. The issue is, true equality of health is impossible, but what is possible is addressing the actual social determinants of health (SDoH). What is also important is understanding what equity is and what equity isn’t, as I have argued in the past. Grifters like James Lindsay and Chris Rufo (along with well-meaning but still wrong institutions) believe that equity is ensuring equal outcomes. This is incorrect. What equity means—in the health sphere—is when “the opportunity to ‘attain their full health potential’ and no one is ‘disadvantaged from achieving this potential because of their social position or other socially determined circumstance’” (Braveman, quoted by the CDC).Therefore, health equity is when everyone has the chance to reach their fill potential, unabated by social determinants. Social conditions and policies strongly influence the health of both individuals and groups and it’s the result of unequal distribution of resources and opportunities. Empirical investigation is pivotal in understanding if a certain inequality is an inequity. And although inequities are a kind of inequality, “inequality” and “inequity” are conceptually distinct (Braveman, 2003).

In this article I will discuss the SDoH, give my argument that we can identify inequity (a kind of inequality) through empirical investigations (meaning that they are avoidable, unfair and unjust). I will then pivot to a real-world example of my argument—that of low birth weight in black American newborns and argue that racism and historical injustices can explain that since non-American black women have children with higher mean birth weights. I will then discuss how blacks who have doctors of of the same race report better care and have higher life expectancies. I will then discuss what can be done about this—and the answer is to educate people on genetic essentialism which leads to racism and racist attitudes.

On SDoH

SDoH include the lack of education, racism, lack of access to health care and poverty. Barr (2011: 64) had a helpful flow chart to understand this issue.

So when it comes to variation in health outcomes, we know that only 20 percent can be attributed to access to medical care, while a whooping 80 percent is attributable to the SDoH:

(Ratcliffe, 2017 also states that about 20 percent of the health of nation is attributed to medical care, 5 percent the result of biology and genes, 20 percent the result of individual action, and 50 percent due to the SDoH.)

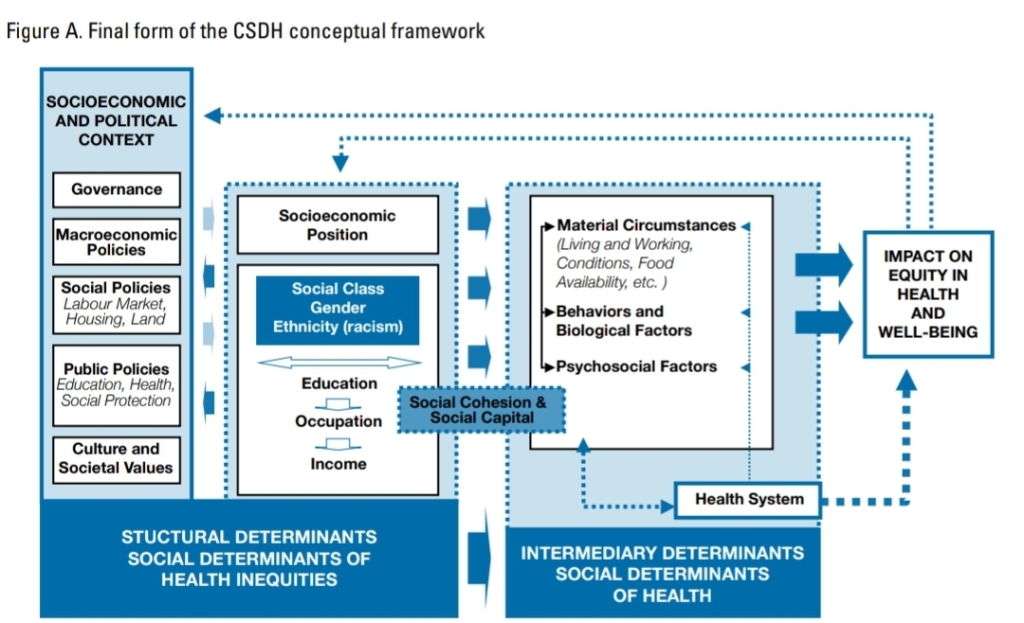

The WHO (2010) also has a Commission on the Social Determinants of Health (CSDH) with a conceptual framework:

This is staggering. For if the social determinants of health are causal for health outcomes, then it comes down to how society is structured along with how we treat certain people and groups. This also could come down to environmental racism—which is the disproportionate exposure of minority groups to environmental hazards. One pertinent example is lead in paint uses in houses in the 80s, where groups actually used blacks as a kind of experiment in seeing the effects of lead. The issue was further exacerbated by Big Lead in trying to argue that the families had a “history of low intelligence” and that it couldn’t be proven that lead had the damaging effects on the children. Not only does environmental racism cause negative health effects, but so does individual racism which is known to have a negative effect on black women. (Racism and stereotypes which lead to self-fulfilling prophecies also cause the black-white crime gap.)

So empirical research—grounded in data and evidence—can help us in understanding whether a given inequality is an inequity. Certain disparities could reflect historical disadvantages which then perpetuate cycles of disadvantage which then reinforce existing power structures and further continue to marginalize certain communities.

The argument

I have constructed an argument that shows what I am talking about:

UO: Unequal outcome

I: Inequality

A: Avoidable

F: Unfair

J: Unjust

E: Empirical investigation

I involves A, F, J. E may reveal instances where I leads to UO and I is associated with F, J, and A.

Premise 1: E -> (A^F^J)

Premise 2: I -> (A^F^J)

Conclusion: E -> ((I -> UO) ^ (A^F^J))

(P1) If empirical investigations (E) reveal instances where avoidable factors (A), unfairness (F) and injustice (J) are present, and (P2) if inequality (I) leads to conditions involving avoidability (A), unfairness (F) and injustice (J), then (Conclusion) empirical investigations (E) could reveal instances where inequality leads to unequal outcomes (UO), and whether or not they are avoidable (A), unfair (F) or unjust (J). Effectively, since inequities are a kind of inequality, then this can identify inequities where they are, and then we can work to fix them.

For instance, birth weight has decreased recently and the effect is more pronounced for black women (Catov et al, 2016) and racism could as well be a culprit (Collins Jr., et al, 2004). There is also evidence that structural racism in the workplace can and has attributed to this (Chantarat et al, 2022). It’s quite clear that racism can explain birth outcome disparities (Dominguez et al, 2010; Alhusen et al, 2016; Dreyer, 2021). Not only does racism contribute to adverse birth outcomes but so too do factors related to environmental racism (Burris and Hacker, 2018). This also has a historical precedent: slavery (Jasienska, 2009). Hereditarians may try to argue that (as always) this difference has a genetic basis. But we know that African women born in Africa are heavier than African American women; black women born in Africa have children with higher mean birth weights than African American women (David and Collins, 1997). Cabral et al (1991) also found the same—non-American black women birthed children that weighed 135 more grams than American black women. Thus, the difference isn’t genetic in nature—it is environmentally caused and it partly stems from slavery. Clearly this discussion shows that my argument has a real-world basis.

How do we reverse these inequities?

Clearly, racism has societal consequences not only for crime and mental illness, but also low birth weight in black American women. The difference can’t be genetic in nature, so it’s obviously environmental/social in nature due to racism, environmental racism. So how can we alleviate this? There are a few ways.

We can improve access to pre-natal care. By ensuring equitable access to pre-natal care, and by expanding Medicaid coverage, we can the begin to address the issue of low black birth weight. We know that when black newborns are cared for by black doctors, they have a better survival rate (Greenwood et al, 2020). We also have an RCT showing that black doctors could reduce the black-white cardiovascular mortality rate by 19 percent (Alsan, Garrick, and Grasiani, 2019). We also know that a higher percentage of black doctors leads to lower mortality rate and better life expectancy (Peek, 2023; Snyder et al, 2023). This isn’t a new finding—we’ve known this since the 90s (Komaramy et al, 1996; Saha et al, 1999). We also know that people who have same-race doctors are more likely to accept much-needed preventative care (LaVeist, Nuru-Jeter, and Jones, 2003). This could then lead to less systemic bias in healthcare, since we know that some of the difference is systemic in nature (Reschovsky and O’Malley 2008: 229, 230). We also know that bias, stereotyping, and prejudice also play a part (Smedley et al, 2003). Such stereotypes are also sometimes unconscious (Williams and Rucker, 2000). The medical system contributes to said disparities (Bird and Clinton, 2001). Blacks who perceived more racism in healthcare felt more comfortable with a black doctor (Chen et al, 2005)—minorities also trust the healthcare system less than whites (Boulware et al, 2003). Lastly, black and white doctors agree that race is a medically relevant data point, but they don’t agree on why (Bonham et al, 2009).

We know that systemic and structural racism exists and that it impacts health outcomes (Braveman et al, 2022). Some may say that systemic and structural racism don’t exist, but this claim is clearly false. They are “are forms of racism that are pervasively and deeply embedded in and throughout systems, laws, written or unwritten policies, entrenched practices, and established beliefs and attitudes that produce, condone, and perpetuate widespread unfair treatment of people of color. They reflect both ongoing and historical injustices” (Braveman et al, 2022). Perhaps the most important way that systemic racism can harm health is through placing people at an economic disadvantage and stress. Environmental racism then compounds this, and then unfair treatment then leads to higher levels of stress which then leads to negative health outcomes.

Lastly a key issue here is the prevalence of racism. We know that it has a slew of negative health effects and that it affects the incidence of the black-white crime gap. But what can be done to alleviate racist attitudes?

Since many racist ideas have a genetically essentialist tilt, then we can use education to ameliorate racist attitudes (Donovan, 2022). We also know that racial essentialist attitudes are related to the belief that evolution has an intentional tilt and that it’s negatively correlated with biology grades (Donovan, 2015). Much of Donovan’s work shows that education can ameliorate racist attitudes which are due to genetic essentialism. We also know that such essentialist thinking is related to misconceptions about heredity and evolution and is correlated with low grades at the end of the semester in beginner biology course (Donovan, 2016). Thus, by providing accurate and understandable education on race, genetics, and evolution, people may be less likely to hold racial essentialist attitudes and more likely to reject racist ideologies. So there are actionable things we can do to combat racism which leads to crime and negative health outcomes for minority groups.

Conclusion

The SDoH play a pivotal role in shaping the health outcomes while perpetuating health inequities. We can, through empirical investigations, ascertain when an inequality is avoidable, unfair and unjust (meaning, when it is an inequity). We can then understand how historical injustices like racism impact marginalized communities which then contribute to negative health outcomes like low birth weight of black American babies. We know that it’s not a genetic difference since non-American black women have children with higher mean birth weights than black American women, and this suggests thar historical injustices and racism are a cause (as Jasienska argues). Further, studies show that when black patients have black doctors, they report better care and have higher life expectancies. Research has also shown that education can play a role in ameliorating genetic essentialist and racist attitudes which then, as I’ve shown, lead to negative health outcomes. The argument I’ve made here has a real-world basis in the case of low birth weight of black American babies.

In sum, committing to social and racial justice can help to change these inequities, and for that, we will have a better and more inclusive society where people’s negative health outcomes aren’t caused by social goings-on. To achieve racial health equity, we must address the avoidable, unfair and unjust factors that contribute to these inequities.