Home » Evolution (Page 6)

Category Archives: Evolution

Evolution and IQ Linkfest IV

1050 words

A decorated raven bone discovered in Crimea may provide insight into Neanderthal cognition (A raven bone discovered in Crimea shows two extra notches, which the researchers say they did intentionally to create a consistent—perhaps symbolic—pattern.)

Just like humans, artificial intelligence can be sexist and racist (Just like Tay. RIP in peace, Tay. Princeton University academics have shown, using a database of over 840 billion words from the Internet, that AI mimics humans and, they too, can apparently become ‘racist and sexist’, just like their creators. A “bundle of names” being associated with European Americans were more likely to be associated with pleasant terms, compared to African Americans who were associated with unpleasant terms. Male names were associated with careers while female names were associated with family. Seems like the AI just gets information and makes a conclusion based on the information, learning as it goes along. I don’t think putting human buzzwords onto AI is practical.)

Childhood lead exposure linked to lower adult IQ (This has been known for, literally, decades. In the new study, every 5 micrograms/dl increase in blood lead levels early in life was shown to decrease IQ by 1.61 points by the time the subjects reached 38 years of age along with reductions in working memory and perceptual reasoning. More shockingly, children who had blood lead levels over 10 micrograms/dl had IQs 4.25 points lower than their peers with low blood lead levels. Some research has shown that for each decrease in 1 point decrease in IQ annual salary decreases by about 200 to 600 dollars. This also shows that high blood-lead levels during childhood cannot be recovered from. There is currently an epidemic of lead poisoning in the Detroit Metropolitan area affecting Arab and African American children (Nriagu et al, 2014), as well as in low-income blacks in Saginaw, Michigan (Smith and Nriagu, 2010) and immigrant children in NYC (Tehranifar et al, 2008). However, see Koller et al (2004) for a different view, showing that blood-lead levels during childhood only account for 4 percent of the variation in cognition whereas parental and social factors account for more than 40 percent. High blood lead levels also lead to an increase in detrimental behavior (Sciarillo, Alexander, and Farrell, 1992). Clearly, measures need to be taken to reduce lead in water around the country as quality of life will improve for everyone.)

Molecular clocks track human evolution (Scientists estimate that we emerged around 200kya in Africa and spread throughout the world 50-100 kya through looking at the ‘molecular clock’—mutation and recombination. Some geneticists estimate that there are between 1.5 and 2 million mutational changes between humans and Neanderthals—estimating a splitting date at 550-750kya.)

How Ants Figured Out Farming Millions of Years Before Humans (Ants have probably been farming since the Chicxulub meteor impact that killed the dinosaurs in one South American rainforest. The researchers found that all fungus-farming ants came from the same ancestor around 60mya. Thirty million years later, another farming species emerged. One of the species was a “more complex agriculturalist” which probably transported its fungus to different locations while the other species were “lower, less complex agriculturalists” which grew fungus capable of “escaping its garden and living independently”. The dry climate allowed the more complex agriculturalists to domesticate the fungus and control the temperature by digging holes for storage.

Mimicking an impact on Earth’s early atmosphere yields all 4 RNA bases (Researchers showed that mimicking an asteroid crash resulted in the formation of the production of all four bases of RNA, the molecules essential for life. Take that, Creationists.)

Study finds some significant differences in brains of men and women (Adjusting for age, researchers found that women had significantly thicker cortices than men while men had higher brain volumes in every area they looked at, including the hippocampus (which plays a part in memory and spatial awareness), the amygdala (plays a role in memory, emotions, and decision-making), striatum (learning, inhibition, and reward-processing), and the thalamus (processing and relaying sensory information to other parts of the body). Men also varied more in cortical thickness and volume much more than women, which supports other studies showing that men only have higher IQ distributions than women, not higher average intelligence. There are, of course, differences between the male and female brain, but I’m now rethinking my position on male/female IQ differences (leaning towards no). Read the preprint here: Sex Differences In The Adult Human Brain: Evidence From 5,216 UK Biobank Participants

Infants show racial bias toward members of own ethnicity, against those of others (Now the study I’ve seen a buzz about the past few days. In one of the studies, researchers found that babies associated other races’ faces with sad music while associating their own races’ face with upbeat, happy music. The second study showed that infants were more likely to learn from their own race than another, which relied on gaze cues. Both studies tested infants between the ages of 6 to 9 months with both studies finding no racial bias in infants less than 6 months of age. The researchers, of course, conclude that this occurs because of lack of contact with other race babies/people. In study one, infants aged 3 to 10 months watched videos with a female adult with a neutral facial expression. The babies heard music before viewing each clip; happy music and same race face; happy music and opposite race face; sad music and same race face; and sad music and opposite race face. They found that babies looked longer at same-race faces with happy music while looking longer at other-race faces with sad music. The second study looked at whether or not babies would be willing to learn from their own race or a different race. Babies aged 6 to 9 months were shown a video in which a female adult appeared and looked at one of the four corners of the screen. In some of the videos, an animal appeared where the person on the screen looked while in other videos, an animal appeared at a non-looked at location. They showed that babies followed the gaze of their own race more often than the other race, showing that infants are “biased” towards learning from their own race. This is clearly evidence for Genetic Similarity Theory. Expect a research article on this soon. Read the abstracts here: Infants Rely More on Gaze Cues From Own-Race Than Other-Race Adults for Learning Under Uncertainty and Older but not younger infants associate own-race faces with happy music and other-race faces with sad music)

Evolution Denial Part II

1450 words

Why do people deny evolution? Not just evolution from single-celled organisms to multicellular lifeforms, but human evolution as well? Most people who deny evolution don’t have the knowledge to assess it correctly. They fall back on the Bible and say “God did this, the Bible says…. God says…” all the while looking at you as a heathen when you attempt to talk some basic biology or, God forbid, the process of evolution.

I met a woman the other day and I asked her what she was studying in school. She tells me anatomy and physiology (right up my alley). So we start talking about some basic anatomy and physiology before I ask the question: “Do you believe in evolution?” She gave me a blank stare and said no.

“Humans as we know them have always existed in this form,” she said. I just started laughing at her ignorance and then she said “Evolution at the macro level is not possible but it is at the micro level”, repeating the same old and tired Creationist talking points. I said to her that there is no evidence for creation and that the evidence we do have points to evolution. I said that the theory of evolution has so much backing, so much evidence, that to believe otherwise you’d have to purposefully close your mind to the truth, to shut out any and all contradictory information.

One of the funniest things she said to me was that she wants to cure diseases. To that, I said if she wants to do that then she must look at diseases from an evolutionary perspective (Gluckman et al, 2011). She said that she doesn’t need to know how diseases were in the past, just how they are today. I also said that if she is studying anatomy and physiology then she must understand that many of our appendages are derived from our hominin ancestors, which began with Erectus as I’ve covered in my article Man the Athlete. Diseases also must be looked at through an evolutionary lens, so if anyone wants to cure diseases, then they must first understand and accept that things are constantly changing and evolving to better survive in that environment.

When I said that there is no evidence for Creation she got really mad. She said that there is no evidence that “we evolved from monkeys” which gave me a good laugh. Even people who believe in evolution still make that mistake of believing that we evolved from monkeys. One of the most common statements from Creationists is “If humans evolved from monkeys then why are monkeys still around?”, wrongly assuming that we literally evolved from monkeys, incorrectly misinterpreting that we share a common ancestor with monkeys 6-12 mya.

About 6mya, there was a chromosomal fusion on chromosome two; two ancestral ape chromosomes fused to make chromosome two (Idjo et al, 1991). That is some nice chromosomal evidence for common descent from our ape cousins. Creationists, however, purport that a gene in chromosome 2, DDX11L2, writing that the “alleged fusion site is not a degenerate fusion sequence but is and, since creation, has been a functional feature in an important gene.” Further, Tomkins’ claim that the fusion site is actually a gene is wrong since the fusion site is more than 1300 bases away from the gene.

The ancestral equivalents of chromosome 2—2p and 2q—fused together in a fusion event some 6mya. This precise fusion site is on chromosome 2 (Hellier et al, 2004). Creationists will say and do anything to attempt to ‘rebut’ this contention. Genetic evidence is the best evidence we have (due to Punctuated Equilibria, which causes the spottiness in the fossil record), and still, these ‘Creationist geneticists’ will do anything they can to attempt to have Evolutionists go on the defensive. However, the onus is on them to disprove the mountains of evidence.

One of the funniest things this woman said to me is that man has always been in this form and that we didn’t evolve from “monkeys”, which is when I said that it’s more complicated than that: we have fish ancestors, named Tiktaalik who had the beginnings of the human arm and hand, along with Pikaia Gracilens—our oldest ancestor. If Pikaia would have died out in the Cambrian explosion some 550 mya, we wouldn’t be here today. We are here today due to the happenstance of numerous accidents of history—contingencies of “just history” to quote Stephen Jay Gould.

Nevertheless, Creationists will always attempt to distort evolutionary science to fit their agendas. Stephen Jay Gould battled Creationists throughout his career. Creationists would quote mine his books to show that Evolutionists do show evidence of “Creation”. One of his most quote mined works is his and Eldredge’s theory of Punctuated Equilibria (1972). Just because a look at the whole fossil record shows species remaining in stasis for most of their history before a short burst of evolutionary change then that must mean that there was a guiding hand involved in the process. Here is a full list of quote mines that Creationists use from Eldredge and Gould.

As you can see, Creationists use any kind of mental gymnastics to disprove evolution. However, no matter how hard you try with Creationists, you can’t educate people into believing in evolution. This is mainly due to the backfire effect which occurs when you show people contradictory information to a dearly held belief and they frantically attempt to gather evidence to shield themselves from contradictory evidence (Nyhan and Reifler, 2010). This cognitive bias holds for more than political debates, though it’s most often seen there. Showing people any kind of contradictory information will have them search and search for anything to shield themselves from the truth. However, no amount of ‘information’ provided by Creationists will disprove evolutionary theory.

Gould and Eldredge aren’t the only Evolutionist that Creationists quote mine–one of the most famous quote mines is from Darwin’s The Descent of Man in which he talks about defending his theory from detractors, mainly the spottiness of the fossil record (which Eldredge and Gould’s Punctuated Equilibria explains). However, this doesn’t stop Creationists—and even some Evolutionists who fall for Creationist trickery—to believe that Darwin was talking about something completely different, in that Darwin was ‘racist’ talking about the ‘superior races’ exterminating the ‘inferior races’. Reading the quote in its entirety, however, shows something completely different. Alas, some people don’t care about facts antruthut and only care about their agenda they attempt to push.

Even setting evolutionary theory aside, basic geology disproves Creationism. The author of the piece, geologist David Montgomery, says that there is a rock outside of his office that proves Creationism wrong. The rock shows that there is more to the geologic record that could be explained by a single grand flood. Now that geologists now have the tools and data to infer that the earth is billions of years old—not thousands as Young Earth Creationists (YECs) claim—YECs change up their interpretation of the Creation story in Genesis to go from literal days to “days in Genesis refer to geological ages”. Clear mental gymnastics in the face of contradictory evidence.

There are five mass extinctions that are accepted in the scientific community (Jablonski, 2001) (though I am reading a book at the moment that talks about nine mass extinction events with Man pushing the tenth, I will return to this in the future). After these contingencies of ‘just history’, we can see that we are incredibly lucky that our ancestors did not die out. From a Pikaia Gracilens surviving the Cambrian radiation, to Tiktaalik and its venturing onto land from the sea and finally the survival of a shrew-like ancestor during the extinction of the dinosaurs, we should thank our lucky stars that these things went our way, because if not, I wouldn’t be sitting here writing this at the moment and you would not be reading this. Evolutionary history is littered with these events—events that, if they went the other way would not lead to the evolution of Man again.

In sum, people who do not believe in evolutionary theory clearly are emotionally invested in believing in a story of Creation—sans evidence, only their belief. On the other hand, evolutionists such as we have all the data on our side when it comes to this debate. Creationists have to use any kind of warped logic to not believe the mountains of evidence that have piled up since Darwin wrote On the Origin. However, as everyone knows, reality isn’t what just what you believe. Just because Creationists handwave away the data that people like us provide to them doesn’t mean that evolution isn’t true.

The Evolution of Human Skin Variation

4050 words

Human skin variation comes down to how much UV radiation a population is exposed to. Over time, this leads to changes in genetic expression. If that new genotype is advantageous in that environment, it will get selected for. To see how human skin variation evolved, we must first look to chimpanzees since they are our closest relative.

The evolution of black skin

Humans and chimps diverged around 6-12 mya. Since we share 99.8 percent of our genome with them, it’s safe to say that when we diverged, we had pale skin and a lot of fur on our bodies (Jablonski and Chaplin, 2000). After we lost the fur on our bodies, we were better able to thermoregulate, which then primed Erectus for running (Liberman, 2015). The advent of fur loss coincides with the appearance of sweat glands in Erectus, which would have been paramount for persistence hunting in the African savanna 1.9 mya, when a modern pelvis—and most likely a modern gluteus maximus—emerged in the fossil record (Lieberman et al, 2006). This sets the stage for one of the most important factors in regards to the ability to persistence hunt—mainly, the evolution of dark skin to protect against high amounts of UV radiation.

After Erectus lost his fur, the unforgiving UV radiation beamed down on him. Selection would have then occurred for darker skin, as darker skin protects against UV radiation. Dark skin in our genus also evolved between 1 and 2 mya. We know this since the melanocortin 1 receptor promoting black skin arose 1-2 mya, right around the time Erectus appeared and lost its fur (Lieberman, 2015).

However, other researchers reject Greaves’ explanation for skin cancer being a driver for skin color (Jablonksi and Chaplin, 2014). They cite Blum (1961) showing that skin cancer is acquired too late in life to have any kind of effect on reproductive success. Skin cancer rates in black Americans are low compared to white Americans in a survey from 1977-8 showing that 30 percent of blacks had basal cell carcinoma while 80 percent of whites did (Moon et al, 1987). This is some good evidence for Greaves’ hypothesis; that blacks have less of a rate of one type of skin cancer shows its adaptive benefits. Black skin evolved due to the need for protection from high levels of UVB radiation and skin cancers.

Highly melanized skin also protects against folate destruction (Jablonksi and Chaplin, 2000). As populations move away from high UV areas, the selective constraint to maintain high levels of folate by blocking high levels of UV is removed, whereas selection for less melanin prevails to allow enough radiation to synthesize vitamin D. Black skin is important near the equator to protect against folate deficiency. (Also see Nina Jablonski’s Ted Talk Skin color is an illusion.)

The evolution of white skin

The evolution of white skin, of course, is much debated as well. Theories range from sexual selection, to diet, to less UV radiation. All three have great explanatory power, and I believe that all of them did drive the evolution of white skin, but with different percentages.

The main driver of white skin is living in colder environments with fewer UV rays. The body needs to synthesize vitamin D, so the only way this would occur in areas with low UV rays.

White skin is a recent trait in humans, appearing only 8kya. A myriad of theories have been proposed to explain this, from sexual selection (Frost, 2007), which include better vitamin D synthesis to ensure more calcium for pregnancy and lactation (which would then benefit the intelligence of the babes) (Jablonski and Chaplin, 2000); others see light skin as the beginnings of more childlike traits such as smoother skin, a higher pitched voice and a more childlike face which would then facilitate less aggressiveness in men and more provisioning (Guthrie, 1970; from Frost, 2007); finally, van den Berghe and Frost (1986) proposed that selection for white skin involved unconscious selection by men for lighter-skinned women which is used “as a measure of hormonal status and thus childbearing potential” (Frost, 2007). The three aforementioned hypotheses have sexual selection for lighter skin as a proximate cause, but the ultimate cause is something completely different.

The hypothesis that white skin evolved to better facilitate vitamin D synthesis to ensure more calcium for pregnancy and lactation makes the most sense. Darker-skinned individuals have a myriad of health problems outside of their ancestral climate, one of which is higher rates of prostate cancer due to lack of vitamin D. If darker skin is a problem in cooler climates with fewer UV rays, then lighter skin, since it ensures better vitamin D synthesis, will be selected for. White skin ensures better and more vitamin D absorption in colder climates with fewer UV rays, therefore, the ultimate cause of the evolution of white skin is a lack of sunlight and therefore fewer UV rays. This is because white skin absorbs more UV rays which is better vitamin D synthesis.

Peter Frost believes that Europeans became white 11,000 years ago. However, as shown above, white skin evolved around 8kya. Further, contrary to popular belief, Europeans did not gain the alleles for white skin from Neanderthals (Beleza et al, 2012). European populations did not lose their dark skin immediately upon entering Europe—and Neanderthal interbreeding didn’t immediately confer the advantageous white skin alleles. There was interbreeding between AMH and Neanderthals (Sankararaman et al, 2014). So if interbreeding with Neanderthals didn’t infer white skin to proto-Europeans, then what did?

A few alleles spreading into Europe that only reached fixation a few thousand years ago. White skin is a relatively recent trait in Man (Beleza et al, 2012). People assume that white skin has been around for a long time, and that Europeans 40,000 ya are the ancestors of Europeans alive today. That, however, is not true. Modern-day European genetic history began about 6,500 ya. That is when the modern-day European phenotype arose—along with white skin.

Furthermore, Eurasians were still a single breeding population 40 kya, and only diverged recently, about 25,000 to 40,000 ya (Tateno et al, 2014). The alleles that code for light skin evolved after the Eurasian divergence. Polymorphisms in the genes ASIP and OCA2 may code for dark and light skin all throughout the world, whereas SLC24A5, MATP, and TYR have a predominant role in the evolution of light skin in Europeans but not East Asians, which suggests recent convergent evolution of a lighter pigmentation phenotype in European and East Asian populations (Norton et al, 2006). Since SLC24A5, MATP, and TYR are absent in East Asian populations, then that means that East Asians evolved light skin through completely different mechanisms than Europeans. So after the divergence of East Asians and Europeans from a single breeding population 25-40kya, there was convergent evolution for light pigmentation in both populations with the same selection pressure (low UV).

Some populations, such as Arctic peoples, don’t have the skin color one would predict they should have based on their ancestral environment. However, their diets are high in shellfish which is high in vitamin D, which means they can afford to remain darker-skinned in low UV areas. UV rays reflect off of the snow and ice in the summer and their dark skin protects them from UV light.

Black-white differences in UV absorption

If white skin evolved to better synthesize vitamin D with fewer (and less intense) UV rays, then those with blacker skin would need to spend a longer time in UV light to synthesize the same amount of vitamin D. Skin pigmentation, however, is negatively correlated with vitamin D synthesis (Libon, Cavalier, and Nikkels, 2013). Black skin is less capable of vitamin D synthesis. Furthermore, blacks’ skin color leads to an evolutionary environmental mismatch. Black skin in low UV areas is correlated with rickets (Holick, 2006), higher rates of prostate cancer due to lower levels of vitamin D (Gupta et al, 2009; vitamin D supplements may also keep low-grade prostate cancer at bay).

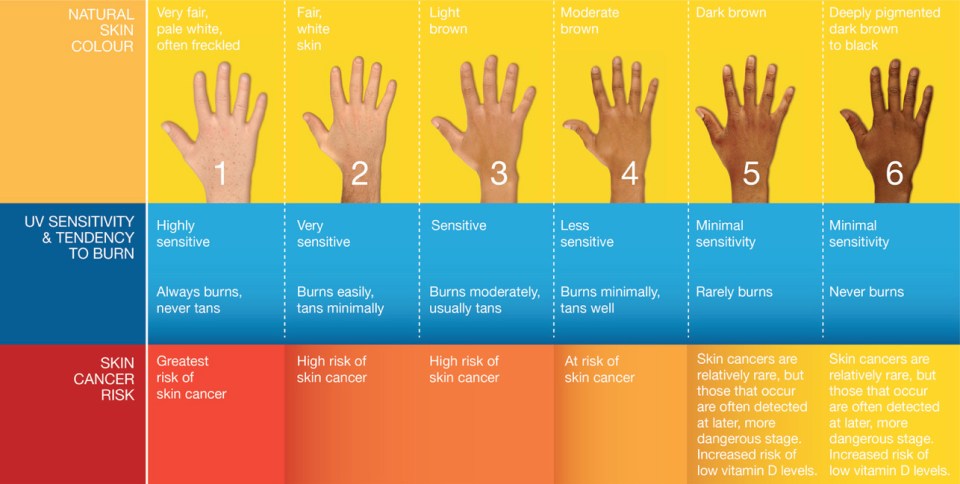

Libon, Cavalier, and Nikkels, (2013) looked at a few different phototypes (skin colors) of black and white subjects. The phototypes they looked at were II (n=19), III (n=1), and VI (n-11; whites and blacks respectively). Phototypes are shown in the image below.

To avoid the influence of solar UVB exposure, this study was conducted in February. On day 0, both the black and white subjects were vitamin D deficient. The median levels of vitamin D in the white subjects was 11.9 ng/ml whereas for the black subjects it was 8.6 ng/ml—a non-statistically significant difference. On day two, however, concentrations of vitamin D in the blood rose from 11.9 to 13.3 ng/ml—a statistically significant difference. For the black cohort, however, there was no statistically significant difference in vitamin D levels. On day 6, levels in the white subjects rose from 11.6 to 14.3 ng/ml whereas for the black subjects it was 8.6 to 9.57 ng/ml. At the end of day 6, there was a statistically significant difference in circulating vitamin D levels between the white and black subjects (14.3 ng/ml compared to 9.57 ng/ml).

Different phototypes absorb different amounts of UV rays and, therefore, peoples with different skin color absorb different levels of vitamin D. Lighter-skinned people absorb more UV rays than darker-skinned people, showing that white skin’s primary cause is to synthesize vitamin D.

UVB exposure increases vitamin D production in white skin, but not in black skin. Pigmented skin, on the other hand, hinders the transformation of 7-dehydrocholesterol to vitamin D. This is why blacks have higher rates of prostate cancer—they are outside of their ancestral environment and what comes with being outside of one’s ancestral environment are evolutionary mismatches. We have now spread throughout the world, and people with certain skin colors may not be adapted for their current environment. This is what we see with black Americans as well as white Americans who spend too much time in climes that are not ancestral to them. Nevertheless, different-colored skin does synthesize vitamin D differently, and knowledge of this will increase the quality of life for everyone.

Even the great Darwin wrote about differences in human skin color. He didn’t touch human evolution in On the Origin of Species (Darwin, 1859), but he did in his book Descent of Man (Darwin, 1871). Darwin talks about the effects of climate on skin color and hair, writing:

It was formerly thought that the colour of the skin and the character of the hair were determined by light or heat; and although it can hardly be denied that some effect is thus produced, almost all observers now agree that the effect has been very small, even after exposure during many ages. (Darwin, 1871: 115-116)

Darwin, of course, championed sexual selection as the cause for human skin variation (Darwin, 1871: 241-250). Jared Diamond has the same view, believing that natural selection couldn’t account for hair loss, black skin and white skin weren’t products of natural selection, but female mate preference and sexual selection (Greaves, 2014).

Parental selection for white skin

Judith Rich Harris, author of the book The Nurture Assumption: Why Kids Turn Out the Way They Do (Harris, 2009), posits another hypothesis for the evolution of light skin for those living in northern latitudes—parental selection. This hypothesis may be controversial to some, as it states that dark skin is not beautiful and that white skin is.

Harris posits that selection for lighter skin was driven by sexual selection, but states that parental selection for lighter skin further helped the fixation of the alleles for white skin in northern populations. Neanderthals were a furry population, as they had no clothes, so, logic dictates that if they didn’t have clothes then they must have had some sort of protection against the cold Ice Age climate, therefore they must have had fur.

Harris states that since lighter skin is seen as more beautiful than darker skin, then if a woman birthed a darker/furrier babe than the mother would have committed infanticide. Women who birth at younger ages are more likely to commit infanticide, as they still have about twenty years to birth a babe. On the other hand, infanticide rates for mothers decrease as she gets older—because it’s harder to have children the older you get.

Harris states that Erectus may have been furry up until 2 mya, however, as I’ve shown, Erectus was furless and had the ability to thermoregulate—something that a hairy hominin was not able to do (Lieberman, 2015).

There is a preference for lighter-skinned females all throughout the world, in Africa (Coetzee et al, 2012); China and India (Naidoo et al, 2016; Dixson et al, 2007); and Latin America and the Philipines (Kiang and Takeuchi, 2009). Light skin is seen as attractive all throughout the world. Thus, since light skin allows better synthesize of vitamin D in colder climes with fewer UV rays, then there would have been a myriad of selective pressures to push that along—parental selection for lighter-skinned babes being one of them. This isn’t talked about often, but infanticide and rape have both driven our evolution (more on both in the future).

Harris’ parental selection hypothesis is plausible, and she does use the right dates for fur loss which coincides with the endurance running of Erectus and how he was able to thermoregulate body heat due to lack of fur and more sweat glands. This is when black skin began to evolve. So with migration into more northerly climes, lighter-skinned people would have more of an advantage than darker-skinned people. Infanticide is practiced all over the world, and is caused—partly—by a mother’s unconscious preferences.

Skin color and attractiveness

Lighter skin is seen as attractive all throughout the world. College-aged black women find lighter skin more attractive (Stephens and Thomas, 2012). It is no surprise that due to this, a lot of black women lighten their skin with chemicals.

In a sample of black men, lighter-skinned blacks were more likely to perceive discrimination than their darker-skinned counterparts (Uzogara et al, 2014). Further, in appraising skin color’s effect on in-group discrimination, medium-skinned black men perceived less discrimination than lighter- and darker-skinned black men. Lastly—as is the case with most studies—this effect was particularly pronounced for those in lower SES brackets. Speaking of SES, lighter-skinned blacks with higher income had lower blood pressure than darker-skinned blacks with higher income (Sweet et al, 2007). The authors conclude that a variety of psychosocial stress due to discrimination must be part of the reason why darker-skinned blacks with a high SES have worse blood pressure—but I think there is something else at work here. Darker skin on its own is associated with high blood pressure (Mosley et al, 2000). I don’t deny that (perceived) discrimination can and does heighten blood pressure—but the first thing that needs to be looked at is skin color.

Lighter-skinned women are seen as more attractive (Stephen et al, 2009). This is because it signals fertility, femininity, and youth. One more important thing it signals is the ability to carry a healthy child to term since lighter skin in women is associated with better vitamin D synthesis which is important for a growing babe.

Skin color and intelligence

There is a high negative correlation between skin color and intelligence, about –.92 (Templer and Arikawa, 2006). They used the data from Lynn and Vanhanen’s 2002 book IQ and the Wealth of Nations and found that there was an extremely strong negative correlation between skin color and IQ. However, data wasn’t collected for all countries tested and for half of the countries the IQs were ‘estimated’ from other surrounding countries’ IQs.

Jensen (2006) states that the main limitation in the study design of Arikawa and Templer (2006) is that “correlations obtained from this type of analysis are completely non-informative regarding any causal or functional connection between individual differences in skin pigmentation and individual differences in IQ, nor are they informative regarding the causal basis of the correlation, e.g., simple genetic association due to cross-assortative mating for skin color and IQ versus a pleiotropic correlation in which both of the phenotypically distinct but correlated traits are manifested by one and the same gene.”

Lynn (2002) purported to find a correlation of .14 in a representative sample of American blacks (n=430), concluding that the proportion of European genes in African Americans dictates how intelligent that individual black is. However, Hill (2002) showed that when controlling for childhood environmental factors such as SES, the correlation disappears and therefore, a genetic causality cannot be inferred from the data that Lynn (2002) used.

Since Lynn found a .14 correlation between skin color and IQ in black Americans, that means that only .0196 percent of the variation in IQ within black American adults can be explained by skin color. This is hardly anything to look at and keep in mind when thinking about racial differences in IQ.

However, other people have different ideas. Others may say that since animal studies find that lighter animals are less sexually active, are less aggressive, have a larger body mass, and greater stress resistance. So since this is seen in over 40 species of vertebrate, some fish species, and over 30 bird species (Rushton and Templer, 2012) that means that it should be a good predictor for human populations. Except it isn’t.

we know the genetic architecture of pigmentation. that is, we know all the genes (~10, usually less than 6 in pairwise between population comparisons). skin color varies via a small number of large effect trait loci. in contrast, I.Q. varies by a huge number of small effect loci. so logically the correlation is obviously just a correlation. to give you an example, SLC45A2 explains 25-40% of the variance between africans and europeans.

long story short: it’s stupid to keep repeating the correlation between skin color and I.Q. as if it’s a novel genetic story. it’s not. i hope don’t have to keep repeating this for too many years.

Finally, variation in skin color between human populations are primarily due to mutations on the genes MC1R, TYR, MATP (Graf, Hodgson, and Daal, 2005), and SLC24A5 (also see Lopez and Alonso, 2014 for a review of genes that account for skin color) so human populations aren’t “expected to consistently exhibit the associations between melanin-based coloration and the physiological and behavioural traits reported in our study” (Ducrest, Keller, and Roulin, 2008). Talking about just correlations is useless until causality is established (if it ever is).

Conclusion

The evolution of human skin variation is complex and is driven by more than one variable, but some are stronger than others. The evolution of black skin evolved—in part—due to skin cancer after we lost our fur. White skin evolved due to sexual selection (proximate cause) and to better absorb UV rays for vitamin D synthesis in colder climes (the true need for light skin in cold climates). Eurasians split around 40kya, and after this split both evolved light skin pigmentation independently. As I’ve shown, the alleles that code for skin color between blacks and whites don’t account for differences in aggression, nor do they account for differences in IQ. The genes that control skin color (about a dozen) pale in comparison to the genes that control intelligence (thousands of genes with small effects). Some other hypotheses for the evolution of white skin are on par with being as controversial as the hypothesis that skin color and intelligence co-evolved—mainly that mothers would kill darker-skinned babies because they weren’t seen as beautiful as lighter-skinned babies.

The evolution of human skin variation is extremely interesting with many competing hypotheses, however, to draw wild conclusions based on just correlations in regards to human skin color and intelligence and aggression, you’re going to need more evidence than just correlations.

References

Bang KM, Halder RM, White JE, Sampson CC, Wilson J. 1987. Skin cancer in black Americans: A review of 126 cases. J Natl Med Assoc 79:51–58

Beleza, S., Santos, A. M., Mcevoy, B., Alves, I., Martinho, C., Cameron, E., . . . Rocha, J. (2012). The Timing of Pigmentation Lightening in Europeans. Molecular Biology and Evolution,30(1), 24-35. doi:10.1093/molbev/mss207

Blum, H. F. (1961). Does the Melanin Pigment of Human Skin Have Adaptive Value?: An Essay in Human Ecology and the Evolution of Race. The Quarterly Review of Biology,36(1), 50-63. doi:10.1086/403275

Coetzee V, Faerber SJ, Greeff JM, Lefevre CE, Re DE, et al. (2012) African perceptions of female attractiveness. PLOS ONE 7: e48116.

Darwin, C. (1859). On the origin of species by means of natural selection, or, the preservation of favoured races in the struggle for life. London: J. Murray.

Darwin, C. (1871). The descent of man, and selection in relation to sex. London: John Murray, Albemarle Street.

Dixson, B. J., Dixson, A. F., Li, B., & Anderson, M. (2006). Studies of human physique and sexual attractiveness: Sexual preferences of men and women in China. American Journal of Human Biology,19(1), 88-95. doi:10.1002/ajhb.20584

Ducrest, A., Keller, L., & Roulin, A. (2008). Pleiotropy in the melanocortin system, coloration and behavioural syndromes. Trends in Ecology & Evolution,23(9), 502-510. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2008.06.001

Frost, P. (2007). Human skin-color sexual dimorphism: A test of the sexual selection hypothesis. American Journal of Physical Anthropology,133(1), 779-780. doi:10.1002/ajpa.20555

Graf, J., Hodgson, R., & Daal, A. V. (2005). Single nucleotide polymorphisms in theMATP gene are associated with normal human pigmentation variation. Human Mutation,25(3), 278-284. doi:10.1002/humu.20143

Greaves, M. (2014). Was skin cancer a selective force for black pigmentation in early hominin evolution? Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences,281(1781), 20132955-20132955. doi:10.1098/rspb.2013.2955

Gupta, D., Lammersfeld, C. A., Trukova, K., & Lis, C. G. (2009). Vitamin D and prostate cancer risk: a review of the epidemiological literature. Prostate Cancer and Prostatic Diseases,12(3), 215-226. doi:10.1038/pcan.2009.7

Guthrie RD. 1970. Evolution of human threat display organs. Evol Biol 4:257–302.

Harris, J. R. (2006). Parental selection: A third selection process in the evolution of human hairlessness and skin color. Medical Hypotheses,66(6), 1053-1059. doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2006.01.027

Harris, J. R. (2009). The nurture assumption: why children turn out the way they do. New York: Free Press.

Hill, Mark E. 2002. Skin color and intelligence in African Americans: A reanalysis of Lynn’s data. Population and Environment 24, no. 2:209–14

Holick, M. F. (2006). Resurrection of vitamin D deficiency and rickets. Journal of Clinical Investigation,116(8), 2062-2072. doi:10.1172/jci29449

Jablonski, N. G., & Chaplin, G. (2000). The evolution of human skin coloration. Journal of Human Evolution,39(1), 57-106. doi:10.1006/jhev.2000.0403

Jablonski, N. G., & Chaplin, G. (2014). Skin cancer was not a potent selective force in the evolution of protective pigmentation in early hominins. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences,281(1789), 20140517-20140517. doi:10.1098/rspb.2014.0517

Jensen, A. R. (2006). Comments on correlations of IQ with skin color and geographic–demographic variables. Intelligence,34(2), 128-131. doi:10.1016/j.intell.2005.04.003

Kiang, L., & Takeuchi, D. T. (2009). Phenotypic Bias and Ethnic Identity in Filipino Americans. Social Science Quarterly,90(2), 428-445. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6237.2009.00625.x

Libon, F., Cavalier, E., & Nikkels, A. (2013). Skin Color Is Relevant to Vitamin D Synthesis. Dermatology,227(3), 250-254. doi:10.1159/000354750

Lieberman, D. E. (2015). Human Locomotion and Heat Loss: An Evolutionary Perspective. Comprehensive Physiology, 99-117. doi:10.1002/cphy.c140011

Lieberman, D. E., Raichlen, D. A., Pontzer, H., Bramble, D. M., & Cutright-Smith, E. (2006). The human gluteus maximus and its role in running. Journal of Experimental Biology,209(11), 2143-2155. doi:10.1242/jeb.02255

López, S., & Alonso, S. (2014). Evolution of Skin Pigmentation Differences in Humans. ELS. doi:10.1002/9780470015902.a0021001.pub2

Lynn, R. (2002). Skin color and intelligence in African Americans. Population and Environment, 23, 365–375.

Mosley, J. D., Appel, L. J., Ashour, Z., Coresh, J., Whelton, P. K., & Ibrahim, M. M. (2000). Relationship Between Skin Color and Blood Pressure in Egyptian Adults : Results From the National Hypertension Project. Hypertension,36(2), 296-302. doi:10.1161/01.hyp.36.2.296

Naidoo, L.; Khoza, N.; Dlova, N.C. A fairer face, a fairer tomorrow? A review of skin lighteners. Cosmetics 2016, 3, 33.

Norton, H. L., Kittles, R. A., Parra, E., Mckeigue, P., Mao, X., Cheng, K., . . . Shriver, M. D. (2006). Genetic Evidence for the Convergent Evolution of Light Skin in Europeans and East Asians. Molecular Biology and Evolution,24(3), 710-722. doi:10.1093/molbev/msl203

Rushton, J. P., & Templer, D. I. (2012). Do pigmentation and the melanocortin system modulate aggression and sexuality in humans as they do in other animals? Personality and Individual Differences,53(1), 4-8. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2012.02.015

Sankararaman, S., Mallick, S., Dannemann, M., Prüfer, K., Kelso, J., Pääbo, S., . . . Reich, D. (2014). The genomic landscape of Neanderthal ancestry in present-day humans. Nature,507(7492), 354-357. doi:10.1038/nature12961

Stephen, I. D., Smith, M. J., Stirrat, M. R., & Perrett, D. I. (2009). Facial Skin Coloration Affects Perceived Health of Human Faces. International Journal of Primatology,30(6), 845-857. doi:10.1007/s10764-009-9380-z

Stephens, D., & Thomas, T. L. (2012). The Influence of Skin Color on Heterosexual Black College Women’s Dating Beliefs. Journal of Feminist Family Therapy,24(4), 291-315. doi:10.1080/08952833.2012.710815

Sweet, E., Mcdade, T. W., Kiefe, C. I., & Liu, K. (2007). Relationships Between Skin Color, Income, and Blood Pressure Among African Americans in the CARDIA Study. American Journal of Public Health,97(12), 2253-2259. doi:10.2105/ajph.2006.088799

Tateno, Y., Komiyama, T., Katoh, T., Munkhbat, B., Oka, A., Haida, Y., . . . Inoko, H. (2014). Divergence of East Asians and Europeans Estimated Using Male- and Female-Specific Genetic Markers. Genome Biology and Evolution,6(3), 466-473. doi:10.1093/gbe/evu027

Templer, D. I., & Arikawa, H. (2006). Temperature, skin color, per capita income, and IQ: An international perspective. Intelligence,34(2), 121-139. doi:10.1016/j.intell.2005.04.002

Uzogara, E. E., Lee, H., Abdou, C. M., & Jackson, J. S. (2014). A comparison of skin tone discrimination among African American men: 1995 and 2003. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 15(2), 201–212. http://doi.org/10.1037/a0033479

van den Berghe PL, Frost P. 1986. Skin color preference, sexual dimorphism and sexual selection: a case of gene-culture coevolution? Ethn Racial Stud 9:87–113.

Diet Or Socializing—What Caused Primate Brain Size To Increase?

1100 words

The social brain hypothesis argues that the human brain did not increase in size to solve increasingly complex problems, but as a means of surviving and reproducing in complex social groups (Dunbar, 2009). The social brain hypothesis is one of the most largely held views when it comes to explaining primate encephalization. However, an analysis of new phylogeny and more primate samples shows that differences in human and non-human primate brain evolution come down to diet, not sociality.

Diet is one of the most important factors in regards to brain and body size. The more high-quality food an animal has, the bigger its brain and body will be. Using a larger sample (3 times as large, 140 primates), more recent phylogenies (which show inferred evolutionary relationships amongst species, not which species is ‘more evolved’ than another), and updated statistical techniques, Decasien, Williams, and Higham (2017) show that diet best predicts brain size in primates, not social factors after controlling for body size and phylogeny (humans were not used because we are an outlier).

The social scheme they used consisted of solitary, pair-living, harem polygyny (one or two males, “a number of females” and offspring), and polygynandry (males and females have multiple breeding partners during the mating season). The diet scheme they used consisted of folivore (leaf-eater), frugivore-folivore (fruit and leaf eater), frugivore (fruit-eater) and omnivore (meat- and plant-eaters).

None of the sociality measures used in the study showed a relative increase in primate brain size variation, whereas diet did. Omnivores have bigger brains than frugivores. Frugivores had bigger brains than folivores. This is because animal protein/fruit contains higher quality energy when compared to leaves. Bigger brains can only evolve if there is sufficient and high-quality energy being consumed. The predicted difference in neurons between frugivores and folivores as predicted by Herculano-Houzel’s neuronal scaling rules was 1.08 billion.

The authors conclude that frugivorous primates have larger brains due to the cognitive demands of “(1) necessity of spatial information storage and retrieval; (2) cognitive demands of ‘extractive foraging’ of fruits and seeds; and (3) higher energy turnover and enhanced diet quality for energy needed during fetal brain growth.” (Decasien, Williams, and Higham, 2017). Clearly, frugivory provided some selection pressures, and, of course, the energy needed to power a larger brain.

The key here is the ability to overcome metabolic constraints. Without that, as seen with the primates that consumed a lower-quality diet, brain size—and therefore neuronal count—was relatively smaller/lower in those primates. Overall brain size best predicts cognitive ability across non-human primates—not encephalization quotient (Deaner et al, 2007). Primate brains increase approximately isometrically as a function of neuron number and its overall size with no change in neuronal density or neuronal/glial cell ratio with increasing brain size (in contrast to rodent brains) (Herculano-Houzel, 2007). If brain size best predicts cognitive ability across human primates and primate brain size increases isometrically as a function of neuron number with no change in neuronal density with increasing brain size, then primates with larger brains would need to have a higher quality diet to afford more neurons.

The results from DeCasien, Williams, and Higham (2017) call into question the social brain hypothesis. The recent expansion of the cerebellum co-evolved with tool-use (Vandervert, 2016), suggesting that our ability to use technology (to crush and mash foods, for instance) was at least as important as sociality throughout our evolution.

The authors conclude that both human and non-human primate brain evolution was driven by increased foraging capability which then may have provided the “scaffolding” for the development of social skills. Increased caloric consumption can afford larger brains with more neurons and more efficient metabolisms. It’s no surprise that frugivorous primates had larger brains than folivorous primates. Just as Fonseca-Azevedo and Herculano-Houzel (2012) observed, primates that consumed a higher quality diet had larger brains.

In sum, this points in the opposite direction of the social brain hypothesis. This is evidence for differing cognitive demands placed on getting foods. Those who could easily get food (folivores) had smaller brains than those who had to work for it (frugivores, omnivores). However, to power a bigger brain the primate needs the energy from the food that takes the complex behavior—and thus larger brain—to obtain. This lends credence to Lieberman’s (2013) hypothesis that bipedalism arose after we came out of the trees and needed to forage for fruit to survive.

Brain size in non-human primates is predicted by diet, not social factors, after controlling for body size and phylogeny. Diet is the most important factor in the evolution of species. With a lower quality diet, larger brains with more neurons (in primates, 1 billion neurons takes 6 kcal per day to power) would not evolve. Brain size is predicated on a high-quality diet, and without it, primates—including us—would not be here today. Diet needs to be talked about a lot more when it comes to primate evolution. If we would have continued to eat leaves and not adopt cooking, we would still have smaller brains and many of the things that immediately came after cooking would not have occurred.

Since we are primates we have the right morphology to manipulate our environment and forage for higher quality foods. But those primates with access to foods with higher quality have larger brains and are thus more intelligent (however, there are instances where primate brain size increases and decreases and it comes back to, of course, diet). Sociality comes AFTER having larger brains driven by nutritional factors—and would not be possible without that. Social factors drove our evolution—no doubt about it. But the importance of diet throughout hominin evolution cannot be understated. Without our high-quality diet, we’d still be like our hominin ancestors such as Lucy and her predecessors. Higher quality diet—not sociality, drives primate brain size.

References

DeCasien, A. R., Williams, S. A. & Higham, J. P. Primate brain size is predicted by diet but not sociality. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 1, 0112 (2017).

Deaner, R. O., Isler, K., Burkart, J., & Schaik, C. V. (2007). Overall Brain Size, and Not Encephalization Quotient, Best Predicts Cognitive Ability across Non-Human Primates. Brain, Behavior and Evolution,70(2), 115-124. doi:10.1159/000102973

Dunbar, R. (2009). The social brain hypothesis and its implications for social evolution. Annals of Human Biology,36(5), 562-572.

Fonseca-Azevedo, K., & Herculano-Houzel, S. (2012). Metabolic constraint imposes tradeoff between body size and number of brain neurons in human evolution. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences,109(45), 18571-18576. doi:10.1073/pnas.1206390109

Herculano-Houzel, S. (2007). Encephalization, neuronal excess, and neuronal index in rodents. Anat. Rec. 290, 1280–1287.

Lieberman, D. (2013). The story of the human body: evolution, health and disease. London: Penguin Books.

Vandervert, L. (2016). The prominent role of the cerebellum in the learning, origin and advancement of culture. Cerebellum & Ataxias,3(1). doi:10.1186/s40673-016-0049-z

Man the Athlete

5450 words

Homo nerdicus or Homo athleticus? Which name more aptly describes Man? Without many important adaptations incurred throughout our evolutionary history, modern Man as you see him wouldn’t be here today. The most important factor in this being our morphology and anatomy which evolved due to our endurance running, hunting, and scavenging. The topics I will cover today are 1) morphological differences between hominin species and chimpanzees; 2) how Man became athletic and bring up criticisms with the model; 3) the evolution of our aerobic physical ability and brain size; 4) an evolutionary basis for sports; and 5) the role of children’s playing in the evolution of human athleticism.

Morphological differences between Man and Chimp

Substantial evolution in the lineage of Man has occurred since we have split from the last common ancestor (LCA) with chimpanzees between 12.1 and 5.3 mya (Moorjani et al, 2016; Patterson et al, 2006). One of the most immediate differences that jump out at you when watching a human and chimpanzee is such stark differences in morphology, in particular, how we walk (pelvic differences) as well as our arm length relative to our torsos. Though we both evolved to be proficient at abilities that had us become evolutionarily successful in the environments we found ourselves in, one species of primate went on to become the apes the took over the world whereas the chimps continued life as the LCA did (as far as we can tell). The evolution of our athleticism is why we have a lean body with the right morphology for endurance running and associated movements. In fact, the evolution of our brain size hinged on a reduction in our fat depots (Navarette, Schaik, and Isler, 2011).

One of the largest differences you can see between the two species is how we walk. Chimps are “specially adapted for supporting weight on the dorsal aspects of middle phalanges of flexed hand digits II–V” (Tuttle, 1967). Meanwhile, humans are specifically adapted for bipedality due to the change in our pelvis over the course of our evolution (Gruss and Schmitt, 2015). Due to staying more arboreal than venturing on the ground, chimp morphology over the course of the divergence became more and more adapted to life in the trees.

Our modern gait is associated with physiologic and anatomic adaptations throughout our evolution, and are not ‘primitive retentions’ from the LCA (Schmitt, 2003). There are very crucial selective pressures that need to be looked at to see which selection pressures caused us to become athletes. Parts of Austripolithicenes still live on in us today, most notably in our lower leg/foot (Prang, 2015). Further, our ancestor, the famous Lucy had the beginnings of a modern pelvis, which was the beginning of the shift to the more energetically efficient bipedality, one thing that fully separates Man from the rest of the animal kingdom.

Of course, no conversation about human evolution would be complete without talking about Erectus. Analysis of 1.5 million-year-old footprints shows that Erectus was the first to have a humanlike weight transfer while walking, confirming “the presence of an energy-saving longitudinally arched foot in H. Erectus.” (Hatala et al, 2016). We have not yet discovered a full Homo erectus foot, but 1.5 million-year-old footprints found in Kenya show that whatever hominin made those prints had a long, striding gait with a full arch (Steudel-Numbers, 2006; Bennett et al, 2009). The same estimates from Steudel-Numbers (2006) show that Erectus nearly halved its travel costs compared to australopithecines. This is due to a longer stride which was much more Manlike than apelike due to a humanlike pelvis and gluteus maximus (Lieberman et al, 2006).

However, the most important adaptations that Erectus evolved was the ability to keep cool while walking long distances. Loss of hair loss specifically allowed individuals to be active in hot climates without overheating. Our ancestors’ hair loss facilitated sweating (Ruxton and Wilkinson, 2011b), which allowed us to become the proficient hunters—the athletes—that we would become. There is also thermoregulatory evidence that endurance running may have been possible for Homo erectus, but not any other earlier hominin (Ruxton and Wilkinson, 2011a) which was the beginnings of our selection to become athletes. The evidence reviewed in Ruxton and Wilkinson (2011a) shows that once hair loss and sweating ability reached human levels, thermoregulation was then possible under the midday sun.

Moreover, our modern gait and bipedalism is 75 percent less costly than quadrupedal/bipedal walking in chimpanzees (Sockel, Raichlen, and Pontzer, 2007), so this extra energy that was conserved with our physiologic and anatomic adaptations due to bipedalism could have gone towards other pertinent metabolic functions—like fueling a bigger brain (more energy could be used to feed more neurons).

Born to run

Before getting into how we are able to run so efficiently, I need to talk about what made it possible for us to be able to have the energy to sustain our distance running. That one thing is eating cooked food (meat). This one seemingly simple thing is the ‘prime mover’ so to speak, of our success as athletes. Eating cooked food significantly increases the amount of energy obtained during digestion. That we could extract more energy out of cooked food—no matter what type of food it was—can not be overstated. This is what gave us the energy to hunt and scavenge. We are, of course, able to hunt/scavenge while fasted, which is an extremely useful evolutionary adaptation which increases important hormones to have us search for food. The hormones released during a fasted state aid in human physiologic/metabolic functioning allowing one who is searching for food more heightened sensibilities.

We are evolutionarily adapted to be endurance runners. Endurance running is defined as the ability to run more than 5 km using aerobic metabolism (Lieberman and Bramble, 2007). Since we are poor sprinters, the idea is that our body has evolved for walking. However, numerous anatomical changes in our phenotypes in comparison to our chimp ancestors have left us some clues. In the previous section, I talked about physical changes that occurred after Man and Chimp diverged, well those evolutionary changes are why we evolved to be athletic.

Endurance running first evolved, most likely due to scavenging and hunting (Lieberman et al, 2009). Through natural selection—survival of the ‘good enough’, those who had better physiologic and anatomic adaptations could reach the animal carcass before other scavengers like vultures and hyenas could get to it. Over time, this substantially changed how we would look. Numerous physiologic changes in our lineage attest to the evolution of our endurance running. The nuchal ligament, as well as the radius of the semicircular canal is larger in Homo sapiens than in chimpanzees or australopithecines. This stabilizes our head while running—something that our ancestors could not do because they didn’t have a canal our size (Bramble and Lieberman, 2004).

Skeletal evidence that points to our evolution as athletes consists of (but not limited to):

- The Nuchal ligament—stabilizes the head

- Shoulder and head stabilization

- Limb length and mass (we have legs longer than our torsos which decreases energy used)

- Joint surface (we can absorb more shock when our feet hit the ground due to a larger surface area)

- Plantar arch (generates spring for running but not walking)

- Calcaneal tuber and Achilles tendon (shorter tuber length leads to a longer Achilles heel stretch, converting more kinetic energy into elastic energy)

So people who had anatomy closer to this in our evolutionary past had more of a success of getting to that animal carcass, divvying it amongst his family/tribe, ensuring the passage of his genes to the next generation. Man had to be athletic in order to be able to run for long distances. Where this would have come in handy the most would have been the Savanna in our ancestral past. Man could now use persistence hunting—chasing animals in the heat of the day—and kill them when they tired out. The evolutionary adaptation sweating due to the loss of our fur is the only reason this is possible.

One of the most important adaptations for endurance running is thermoregulation. All humans are adapted for long range locomotion rather than speed and to dump rather than retain heat (Lieberman, 2015). This is one of the most important adaptations we evolved that had us become successful endurance runners. We could chase down prey and wait for our prey to become exhausted/overheat and then we would move in for the kill. Of course, intelligence and sociality come into play as we needed to create hunting bands, but without our superior endurance running capabilities—that no other animal in the animal kingdom has—we would have gone down a completely different evolutionary path than the one we went down. Our genome has evolved to support endurance running (Mattson, 2012). Since there is an association between too much sitting and all-cause mortality (Biddle et al, 2016), this is yet more evidence that we evolved to be mobile, not sedentary hominins.

Further evidence that we evolved to be athletic is in our hands. When you think about our hands and how we can manipulate our environments with them—what sets us apart from every other species—then, obviously, in our evolutionary past, those who were more successful would have had a higher chance of reproducing. Aggressive clubbing and throwing are thought to be one of the earliest hominin specializations. If true, then those who could club and throw best would have the best chance of passing their genes to the next generation, thusly selecting for more efficient hands (Young, 2003). While we may have evolved more efficient hands over time warring with other hominins, some are more prone to disk herniation.

Plomp et al (2015) propose the ‘ancestral shape hypothesis’ which is derived from studying bipedalism. They propose that those who are more prone to disk herniation preferentially affects those who have vertebrae “towards the ancestral end of the range of shape variation within H. sapiens and therefore are less well adapted for bipedalism” (Plomp et al, 2015). One of the most amazing things they discovered was that humans with signs of intervertebral disc herniation are “indistinguishable from those of chimpanzees.” Of course, due to this, we should then look towards evolutionary biology in regards to a lot of human ailments (which I have also argued here on dietary evolutionary mismatches as well as on obesity).

Of course there are some naysayers arguing that endurance running didn’t drive our evolution. He wrongly states that it’s about what drove the evolution of our bipedalism; however, what the endurance running hypothesis argues is that there are certain physiologic and anatomic changes that only could have occurred from endurance running. Better endurance runners got selected for over time, leading to novel adaptations that stayed in the gene pool and got selected for. One thing is a larger gluteus maximus. A humanlike pelvis is found in the fossil record as far back as 1.9 mya in Erectus (Lieberman et al, 2006). Furthermore, longer toes had a larger mechanical cost, and were thusly selected against, which also helped in the evolution of our endurance running (Rolian et al, 2009). All in all, there are too many adaptations that our bodies have that can only be explained by adapting to endurance running. Just because we may have gotten to the weaker animals sometimes doesn’t falsify the hypothesis; Man still needed to sweat and persist in the hot mid-day temperatures chasing prey.

Brain size and aerobic physical capacity

When speaking about the increase in our brain size/neuronal count, fire/cooking, the social brain hypothesis, and other theories are brought up first. Erectus had a lot of humanlike qualities, including the ability to control/use fire (Berna et al, 2012), and the appearance of our modern gait/stride which first appeared in Erectus (Steudel-Numbers, 2006; Bennet et al, 2009). This huge change also occurred around the time our lineage began cooking meat/using fire. Without the increased energy from cooking, we wouldn’t be able to hunt for too long. However, we do have very important specific adaptations during a fasted state—the release of hormones such as catecholamines (adrenaline and noradrenaline) which have as react faster to predators/possible prey. Though, a plant-based diet wouldn’t cut it in regards to our daily energy requirements to feed our huge brain with a huge neuronal count (Fonseca-Azevedo and Herculano-Houzel, 2012). Cooked meat is the only way we’d be able to have enough energy required to hunt game.

What kind of an effect did it have on our cranial capacity/evolution?

Four groups of mice selectively bred for high amounts of “voluntary wheel-running”, ran 3 times further than the controls which increased Vo2 max in the mice. Those mice had higher levels of BDNF (Brain Derived Neurotrophic Factor) several days after the experiment concluded as well as also showing greater cell creation in the hippocampus when allowed to run compared to the controls. In two lines of selected mice, the hormone VEGF (Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor) which was correlated with higher muscle capillary density compared to controls. This shows that the evolution of endurance running in mice leads to important hormonal changes which then affected brain growth (Raichlen and Polk, 2012).

The amount of oxygen our brains use increased by 600 percent compared to 350 percent for our brain size over the course of our evolutionary history. This is important. What would cause an increase in oxygen consumption to the brain? Endurance running. There was further selection in our skeleton for endurance running in our morphology such as the semicircular canal radii. The first humanlike semicircular canal radii were found in Erectus (Spoor, Wood, and Zonneveid, 1994). This meant that we had the ability for running and other agile behaviors which were then selected for. There is also little to no activation of the gluteus medius while walking (Lee et al, 2014), implying that it evolved for more efficient endurance running.

Controlling for body mass in humans, extinct hominins and great apes, Raichlen and Polk (2012) found significant positive correlations with encephalization quotient and hindlimb length (0.93), anterior and posterior radii (0.77 and 0.66 respectively), which support the idea that human athletic ability is tied to neurobiological evolution. A man that was a better athlete compared to another would have a better chance to pass on his genes, as physical fitness is a good predictor of biological fitness. Putting this all together, selection improved our aerobic capacity over our evolutionary history by specifically altering signaling systems responsible for metabolism and oxygen intake (BDNF, VEGF, and IGF-1 (insulin-like growth factor 1), responsible for the regulation of growth hormone), which are important for blood flow, increased muscle capillary density, and a larger brain.

Putting this all together, selection improved our aerobic capacity over our evolutionary history by specifically altering signaling systems responsible for metabolism and oxygen intake (BDNF, VEGF, IGF-1). More evidence is needed to corroborate Raichlen and Polk’s (2012) hypothesis. However, with what we know about aerobic capacity and the hormones that drive it and brain size, we can make inferences based on the available data and say, with confidence, that part of our brain evolution was driven by our increased aerobic capacity/morphology, with the catalyst being endurance running. Though with our increased proclivity for athleticism and endurance running, when we became ‘us’, this just shifted the competition and athletic competition—which, hundreds of thousands/millions of years ago would mean life or death, mate or no mate, food or no food.

Clearly, without the evolution of our bipedalism/athleticism we wouldn’t have evolved the brains we have and thus we would be something completely different today.

Sport and evolutionary history

We crowd into arenas to watch people compete against each other in athletic competition. Why? What are the evolutionary reasons behind this? One view is that sport (and along with it playing) was a way for men to get practice hunting game, with playing also affecting children’s ability to assess the strength of others (Lombardo, 2012).

In an evolutionary context, sports developed as a way for men to further develop skills in order to better provide for his family, as well as assessing other men’s physical strength so he can adapt his fighting to how his opponent fights in a possible future situation. Men would then be selected for these advantageous traits. You see people crowd into arenas to watch their favorite sports teams. We are ‘wired’ to like these types of competitions, which then leads to more competition. Since we evolved to be athletes, then it would stand to reason that we would like to watch others be athletic (and hit each other as hard as they can), as a type of modern-day gladiator games.

Better hunters have better reproductive success (Smith, 2004). Further, hunter-gatherer men with lower-pitched voices have more children, while men with higher-pitched voices had higher child mortality rate (Apicella, Feinberg, and Marlowe, 2007). This signals that the H-G men with more children have higher testosterone than others, which then attracts more women to them. Champion athletes, hunters, and warriors all obtain high reproductive success. Women are sexually attracted to certain traits, which events of human athleticism show. However, men follow sports more closely than women (Lombardo, 2012), and for good reason.

Men may watch sports more than women since, in an evolutionary context, they may learn more about potential allies and who to steer clear from because they would get physically dominated. Further, men could watch the actions of others at play and mimic their actions in an attempt to gain higher status with women. Another reason is a man’s character: you can see a man’s character during sports competition and by watching one’s actions closely during, for instance, playing, you can better ascertain their motivations during life or death situations. Men may also derive thrills from watching “idealized men” perform athletic activities. These are consistent with Lombardo’s (2012) male lek hypothesis, “where male physical prowess and the behaviors important in conflict and cooperation are displayed by athletes and evaluated primarily by male, not female, spectators.”

Testosterone changes based on whether one’s favorite sports team wins or loses (Bernhardt et al, 1998). This is important. Testosterone does change under stressful/group situations. Testosterone is also argued to have a role in the search for, and maintenance of social status (Eisenegger, Haushofer, and Fehr, 2011). Testosterone responses to competition in men are also related to facial masculinity (Pound, Penton-Voak, and Surrin, 2009). Male’s physical strength is also signaled through facial characteristics of dominance and masculinity, considered attractive to women (Fink, Neave, and Seydel, 2007). Since testosterone fuels both competition, protectiveness and confidence (Eisenegger et al, 2016), a woman would be attracted to a man’s athleticism/strength, which would then be correlated with his facial structure further signaling biological fitness to possible mates. Testosterone doesn’t cause prostate cancer, as is commonly stated (Stattin et al, 2003; Michaud, Billups, and Partin, 2015). Testosterone is a beneficial hormone; you should be worried way more about low T than high T. Further, young men interacting with similar young men increases testosterone while interacting with dissimilar men decreases testosterone (DeSoto et al, 2009). This lends credence to the hypothesis that testosterone raises in response to male-male competition.

Since testosterone is correlated with the above traits, and since athletes have higher testosterone than non-athletes (Wood and Stanton, 2011) then certain types of males would be left in the dust. Athleticism can be looked at as a way to expend excess energy. Those with more excess energy would be more sexually attractive to women and mating opportunities would increase. This is why it’s ridiculous to believe that we evolved to be the ‘nerds’ of the animal kingdom when so much of our evolutionary success has hinged on our athleticism and superior endurance running and other athletic capabilities.

Playing

Child’s play is how children feel out the world in a ‘setting’ in which there are no real-world consequences so they can get a feel for how the world really is. Human babes are born helpless, yet with large heads. Natural selection has lead to large brains to care for children, causing earlier childbirths and making children more helpless, which selected for higher intelligence causing a feedback loop (Piantadosi and Kidd, 2016). They show that across the primate genera, the helplessness of an infant is an extremely strong predictor of adult intelligence.

Indeed, a lot of the crucial shaping of our intelligence and motor capabilities are developed in our infancy and early childhood, which we have over chimpanzees. Blaisdell (2015) defines play as: “an activity that is purposeless in that it tends to be detached from the outcome, is imperfect from the goal-directed form of the activity, and that tends to occur when the individual is in a non-stressed state.” Playing is just a carefree activity that children do to get a feel for the world around them. During this time, skills are honed that, in our ancestral past, allowed us to survive and prosper during times of need (persistence hunting, scavenging, etc).

Anthropological evidence also suggests that the existence of extended childhood in humans adapted to establish the skills and knowledge needed to be a proficient hunter-gatherer. Since there are no real-world outcomes to playing (other than increased/decreased pride), a child can get some physical experience without suffering the real life repercussions of failing. Studies of hunter-gatherers show that play fosters the skills needed to be proficient in tool-making and tool-use, food provisioning, shelter, and predator defense. Play time also hones athletic ability and the brain-body connection so one can be prepared for a stressful situation. In fact, children’s fascination with ‘why’ questions make them ‘little philosophers’, which is an evolutionary adaptation to prepare for possible future outcomes.

Think of play fighting. While play fighting, the outcome has no important real life applications (well, the loser’s pride is hit) and what is occurring is the honing of skills that are useful to survival. During our ancestral evolution, play fighting between brothers could have honed the skills needed during a life our death situation when another band of humans was encountered. As you begin to associate certain movements with certain events, you then become better prepared subconsciously for when novel situations occur. The advantage of an extended childhood with large amounts of play time allow the brain and body to make certain connections between things and when these situations arise during a life or death situation, the brain-body will already have the muscle memory to handle the situation.

Conclusion

Studying our evolution since the divergence between Man and chimp, we can see the types of adaptations that we have incurred over our evolutionary history that have lead to us being specifically adapted for long-term endurance running. The ability to sweat, which, as far as we know began with Erectus, was paramount in our history for thermoregulation. Looking at the evolution of our pelvis, toes, gluteal muscles, heads, shoulders, brains, etc all will point to how they are adapted to a bipedal ape that is born to run—born to be an athlete. Without our athleticism, our intelligence wouldn’t be possible. We have a brain-body connection, our brain isn’t the only thing that drives our body, the two work in concert giving each other information, reacting to familiar and novel stimuli. That’s for another time though.

We didn’t evolve to be Homo nerdicus, we evolved to be Homo athleticus. This can be seen with how exercise has such a huge impact on cognition. We can further see the relationship between our athletic ability and our cognition/brain size. Without the way our evolution happened, Man—along with everything else you see around you—would not be here today. In a survival situation—one in which society completely breaks down—one who has better control over his body and motor functions/capabilities will outlast those who do not. Ultimate and conscious control over our bodies, reacting to stimuli in the environment is fostered in our infancy during our play time with others. Playing allows an individual to get experience in a simulated event, getting important muscle memory to react to future situations. The brain itself, of course, is being molded during playing as well. This just attests to the large part that playing has on cognition, survival skills and athletic ability over our evolutionary history.

Aerobic capacity throughout our evolutionary history beginning with Erectus was paramount for what we have become today. Without the evolution of certain muscles like our gluteus maximus along with certain appendages that gave us the ability to trek/run long distances, we would have lost a very important variable in our brain evolution. Aerobic activity increases blood flow to the brain and so the more successful endurance runners/hunters would increase their biological fitness (as seen in Smith, 2004) and thusly those who were more athletically successful would have more children, increasing selection for important traits for endurance running/athleticism throughout our evolutionary history.

We still play sports today since we love competition. Testosterone fuels the need for competition and sports is the best way to engage in competition in the modern day. Women are much more attracted to men with higher levels of testosterone which in turn means a more masculinized face which signals dominance and testosterone levels during competition. Women are attracted to men with higher levels of testosterone and a more masculinized face. This just so happens to mirror athletes, who have both of these traits. However, being in top physical condition is not enough; an athlete must also have a strong mental background if, for instance, they wish to break world records (Lippi, Favaloro, and Guidi, 2008).

The evolution of human playing ties this together. These sports competitions that we have made hearken back to our evolutionary past and show who would have fared best in the past. When we play, we are feeling our competition and who we can possibly make allies with/watch out for due to their actions during playing. One would also see who he would likely need to avoid and form an alliance with as to not get on his bad side and prevent a loss of status in his band. This is what it really comes down to—loss of status. Higher-status men do have higher levels of testosterone, and by one losing to a more capable person, they show that they aren’t fit to lead and they fall in the social hierarchy.

To fully understand human evolution and how we became ‘us’ we need to understand the evolution of our morphology and how it pertains to things such as our cognition and overall brain size and what advantages/disadvantages it afforded us. Whatever the case may be, it’s clear that we have evolved to be athletic and any change in that makeup will lead to a decrease in quality of life.

Homo athleticus, not Homo nerdicus, best describes Man.

References

Apicella, C. L., Feinberg, D. R., & Marlowe, F. W. (2007). Voice pitch predicts reproductive success in male hunter-gatherers. Biology Letters,3(6), 682-684. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2007.0410