Home » Posts tagged 'Racial Differences' (Page 3)

Tag Archives: Racial Differences

Steroid Mythconceptions and Racial Differences in Steroid Use

2000 words

Steroids get a bad reputation. It largely comes from movies and people’s anecdotal experiences and repeating stories they hear from the media and other forms of entertainment, usually stating that there is a phenomenon called ‘roid rage’ that makes steroid users violent. Is this true? Are any myths about steroids true, such as a shrunken penis? Are there ways to off-set it? Steroids and their derivatives are off-topic for this blog, but it needs to be stressed that there are a few myths that get pushes about steroids and what it does to behavior, its supposed effects on aggression and so forth.

With about 3 million AAS (ab)users (anabolic-androgenic steroids) in America (El Osta et al, 2016), knowing the effects of steroids and similar drugs such as Winny (a cutting agent) would have positive effects, since, of course, athletes mostly use them.

Shrunken testicles

This is, perhaps, one of the most popular. Though the actual myth is that AAS use causes the penis to shrink (which is not true), in reality, AAS use causes the testicles to shrink by causing the Leydig cells to decrease natural testosterone production which then decreases the firmness and shape of the testicles which then results in a loss of size.

In one study of 772 gay men using 6 gyms between the months of January and February (and you need to think of the type of bias there that those people who are ‘Resolutioners’ would be more likely to go to the gym those months), a questionnaire was given to the men. 15 .2 percent of the men had used, with 11.7 percent of them injecting within the past 12 months. HIV positive men were more likely to have used in the past compared to negative men (probably due to scripts). Fifty-one percent of them reported testicular atrophy, and they were more likely to report suicidal thoughts (Bolding, Sherr, and Elford, 2002). They conclude:

One in seven gay men surveyed in central London gyms in 2000 said they had used steroids in the previous 12 months. HIV positive men were more likely to have used steroids than other men, some therapeutically. Side effects were reported widely and steroid use was associated with having had suicidal thoughts and feeling depressed, although cause and effect could not be established. Our findings suggest that steroid use among gay men may have serious consequences for both physical and mental health.

Of course, those who (ab)use substances have more psychological problems than those who do not. Another study of 203 bodybuilders found that 8 percent (n = 17) found testicular atrophy (for what it’s worth, it was an internet survey of drug utilization) (Perry et al, 2005). Another study found that out of 88 percent of individuals who abused the drug complained of side-effects of AAS use, about 40 percent described testicular atrophy (Evans, 1997), while testicular atrophy was noted in about 50 percent of cases (sample size n = 24) (Darke et al, 2016).

Sperm production

One study of steroid users found that only 17 percent of them had normal sperm levels (Torres-Calleja et al, 2001), this is because exogenous testosterone will result in the atrophy of germinal cells which cause a decrease in spermatogenesis. Though, too, increased AAS (ab)use later into life may lead to infertility later in life. Knuth et al (1989) also studied 41 bodybuilders with an average age of 26.7. They went through a huge laundry list of different types of steroids they have taken over their lives. Nineteen of the men were still using steroids at the time of the investigation (group I), whereas 12 of them (group II) stopped taking steroids 3 months prior, while 10 of them (group III) stopped steroid use 4 to 24 months prior.

They found that only 5 of them had sperm counts below the average of 20 million sperm per square ml, while 24 of the bodybuilders showed these symptoms. No difference between group I and II was noticed and group III (the group that abstained from use for 4 to 24 months) largely had sperm levels in the normal range. So, the data suggests that even in cases of severe decrease of sensitivity to androgens due to AAS (ab)use, spermatogenesis may still continue normally in some men, even when high levels of androgens are administered exogenously, while even after prolonged use it seems it is possible for sperm levels to go back to the normal range (Knuth et al 1989).

Aggression and crime

Now it’s time for the fun part and my reason for writing this article. Does (ab)using steroids cause someone to go into an uncontrollable rage, a la the Incredible Hulk when they inject themselves with testosterone? The media has latched into the mind of many, with films and TV shows showing the insanely aggressive man who has been (ab)using AAS. But how true is this? A few papers have shown that this phenomenon is indeed true (Konacher and Workman, 1989; Pope and Katz, 1994), but how true is it on its own, since AAS (ab)users are known to use multiple substances???

Konacher and Workman (1989) is a case study done on one man who had no criminal history, who began taking AASs three months before he murdered his wife, and they conclude that AAS can be said to be a ‘personality changer’. Piacetino et al (2015) conclude in their review of steroid use and psychopathology in athletes that “AAS use in athletes is associated with mood and anxiety disturbances, as well as reckless behavior, in some predisposed individuals, who are likely to develop various types of psychopathology after long-term exposure to these substances. There is a lack of studies investigating whether the preexistence of psychopathology is likely to induce AAS consumption, but the bulk of available data, combined with animal data, point to the development of specific psycho-pathology, increased aggressiveness, mood destabilization, eating behavior abnormalities, and psychosis after AAS abuse/dependence.” I, too, would add that since most steroid abuse are polysubstance abusers (they use multiple illicit drugs on top of AAS), that the steroids per se are not causing crime or aggressive behavior, it’s the other drugs that the steroid (ab)user is also taking. And there is evidence for this assertion.

Lundholm et al (2015) showed just that: that AAS (ab)use was confounded with other substances used while the individual in question was also taking AAS. They write:

“We found a strong association between self-reported lifetime AAS use and violent offending in a population-based sample of more than 10,000 men aged 20-47 years. However, the association decreased substantially and lost statistical significance after adjusting for other substance abuse. This supports the notion that AAS use in the general population occurs as a component of polysubstance abuse, but argues against its purported role as a primary risk factor for interpersonal violence. Further, adjusting for potential individual-level confounders initially attenuated the association, but did not contribute to any substantial change after controlling for polysubstance abuse.“

Even The National Institute of Health (NIH) writes: “In summary, the extent to which steroid abuse contributes to violence and behavioral disorders is unknown. As with the health complications of steroid abuse, the prevalence of extreme cases of violence and behavioral disorders seems to be low, but it may be underreported or underrecognized.” We don’t know whether steroids cause aggression or more aggressive athletes are more likely to use the substance (Freberg, 2009: 424). Clearly, the claims of steroids causing aggressive behavior and crime are overblown and there has yet to be a scientific consensus on the matter. A great documentary on the matter is Bigger, Stronger, Faster, which goes through the myths of testosterone while chronicling the use of illicit drugs in bodybuilding and powerlifting.

This, too, was even seen in one study where men were administered supraphysiologic doses of testosterone to see its effects on muscle size and strength since it had never been tested; no changes in mood or behavior occurred (Bhasin et al, 1996). Furthermore, injecting individuals with supraphysiological doses of testosterone as high as 200 and 600 mg per week does not cause heightened anger or aggression (Tricker et al, 1996; O’Connor et, 2002). Testosterone is one of the most abused AASs around, and if a heightened level of T doesn’t cause crime, nor can testosterone levels being higher this week compared to last seem to be a trigger for crime, we can safely disregard any claims of ‘roid rage’ since they coincide with other drug use (polysubstance abuse). So since we know that supraphysiologic doses of testosterone don’t cause crime nor aggression, we can say that AAS use, on its own (and even with other drugs) does not cause crime or heightened aggression since aggression elevates testosterone secretion, testosterone doesn’t elevate aggression.

One review also suggests that medical issues associated with AAS (ab)use are exaggerated to deter their use by athletes (Hoffman and Ratamess, 2006). They conclude that “Existing data suggest that in certain circumstances the medical risk associated with anabolic steroid use may have been somewhat exaggerated, possibly to dissuade use in athletes.”

Racial differences in steroid use

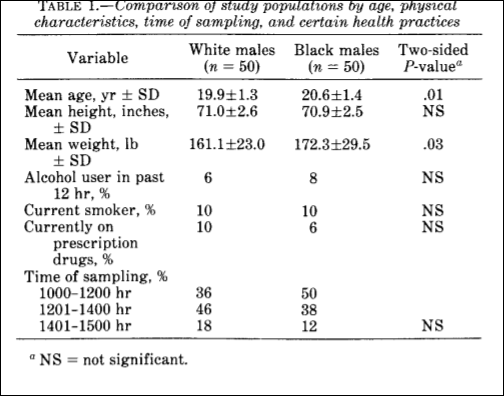

Irving et al (2002) found that 2.1 percent of whites used steroids, whereas 7.6 percent of blacks did; 6.1 percent of ‘Hispanics’ use them within the past 12 months, and a whopping 14.1 percent of Hmong Chinese used them; 7.9 percent of ‘other Asians’ used them, and 3,1 percent of ‘Native Americans’ did with 11.3 percent of mixed race people using them within the past 12 months to gain muscle. Middle schoolers were more likely to use than high schoolers, while people from lower SES brackets were more likely to use than people in higher SES brackets.

Stilger and Yesalis (1999: 134) write (emphasis mine):

Of the 873 high school football players participating in the study, 54 (6.3%) reported having used or currently using AAS. Caucasians represented 85% of all subjects in the survey. Nine percent were African-American while the remainder (6%) consisted of Hispanics, Asian, and other. Of the AAS users, 74% were Caucasian, 13% African American, 7% Hispanic, and 3% Asian, x2 (4,854 4) 4.203, p 4 .38. The study also indicated that minorities are twice as likely to use AAS as opposed to Caucasians. Cross tabulated results indicate that 11.2% of all minorities use/used AAS as opposed to 6.5% of all Caucasians (data not displayed).

One study even had whites and blacks reporting the same abuse of steroids in their sample (n = 10,850 ‘Caucasians’ and n = 1,883 black Americans), with blacks reporting, too, lower levels of other drug abuse (Green et al, 2001). Studies indeed find higher rates of drug use for white Americans than other ethnies, in college (McCabe et al, 2007). Black Americans also frequently underreport and lie about their drug use (Ledgerwood et al, 2008; Lu et al, 2001). Blacks are also more likely to go to the ER after abusing drugs than whites (Drug Abuse Warning Network, 2011). Bauman and Ennett (1994) also found that blacks underreport drug use whereas whites overreport.

So can we really believe the black athletes who state that they do not (ab)use AAS? No, we cannot. Blacks like about any and all drug use, so believing that they are being truthful about AAS (ab)use in this specific instance is not called for.

Conclusion

Like with all things you use and abuse, there are always side-effects. Though, the media furor one hears regarding AAS and testosterone (ab)use are largely blown out of proportion. The risks associated with AAS (ab)use are ‘transient’, and will subside after one discontinues using the drugs. Blacks seem to take more AAS than whites, even if they do lie about any and all drug use. (And other races, too, seem to use it at higher rates than whites.) Steroid use does not seem to be ‘bad’ if one knows what they’re doing and are under Doctor’s supervision, but even then, if you want to know the truth about AAS, then you need to watch the documentary Bigger, Stronger, Faster. I chalk this up to the media themselves demonizing testosterone itself, along with the ‘toxic masculinity’ and the ‘toxic jock effect‘ (Miller, 2009; Miller, 2011). Though, if you dig into the literature yourself you’ll see there is scant evidence for AAS and testosterone (ab)use causing crime, that doesn’t stop papers like those two by Miller talking about the effects of ‘toxic jocks’ and in effect, deriding masculine men and with it the hormone that makes Men men: testosterone. If taken safely, there is nothing wrong with AAS/testosterone use.

(Note: Doctor’s supervision only, etc)

Smoking and Race Part II

1750 words

Almost two years ago, I wrote an article on smoking and race, discussing racial differences in smoking, the brains smoked, and biochemical differences brought on by different physiological differences when smoke is inhaled. In this article, I will look at how smoking can be prevented for all race/ethnies, the contribution of smoking to the black/white difference in mortality, and certain personality traits that may have one more likely to pick up the habit.

Tobacco and poverty are “inextricably linked“, with smoking contributing to more than 10 percent of household income among those in poverty. Tobacco has even been said to be a ‘social justice issue‘ since tobacco use is more prevalent in lower-income communities.

It is true that advertisements are concentrated around certain areas to target certain sociodemographic communities (Seidenberg et al, 2010). They looked at two communities in Boston, Massachusets, one high -income non-minority population, and the other a minority low-income population. They found that the low-income community was more likely to have stores which had larger advertisements, have more stores selling tobacco, promote menthol cigarettes (which low-income people are more likely to smoke, mainly blacks), and finally that advertisements for cigarettes would be more likely to be found 1000 feet away from a school zone in low-income communities compared to high-income communities.

They say that their study shows “evidence that features of tobacco advertising are manipulated to attract youth or racial minority sub-groups, and these features are disproportionately evident in low income, minority communities.” So, according to analysis, at least in the urban area of Dorchester, near Boston, if advertisements were to be lessened near schools, along with fewer overall advertisements, the percentage of minority smokers would decrease. (This same effect of low SES affecting the odds of smoking was also seen in a sample of Argentine children; Linetzky et al, 2012).

Higher SES communities have fewer tobacco advertisements than lower SES communities (Barbeau et al, 2005; Hillier et al, 2015). Big Tobacco (along with Big Food and Big Soda) advertise the most in lower-income communities, which then have deleterious health consequences in those populations, further increasing national health spending per year.

Among Americans, as income increases, smoking decreases:

Nationwide, the Gallup-Healthways Well-Being Index reveals that 21% of Americans say they smoke. As the accompanying graph illustrates, the likelihood of smoking generally increases as annual incomes decrease. One exception to this pattern occurs among those making less than $6,000 per year, an income bracket often skewed because many in that bracket are students. Among those making $6,000 to $11,999 per year, 34% say they smoke, while only 13% in the top two income brackets (those with incomes of at least $90,000 per year) say the same — a 21 percentage-point gap.

The Well-Being Index also confirms distinctions in U.S. smoking rates relating to gender and race. Among respondents, 23% of men and 19% of women say they smoke. Blacks are the most likely to smoke (23%) and Asians are least likely to smoke (12%). Hispanics and whites fall in between, at 17% and 20%, respectively.

Further, according to the CDC, the prevalence of smoking of people with a GED is at 40 percent, the highest amongst any SES group. The fact that tobacco companies attempt to advertise in low-income areas and to women is also well-studied. These factors combined to then cause higher rates of smoking in lower-income populations, and blacks are some of the most affected. There are also a slew of interesting physiological differences between blacks and whites regarding smoking.

Ho and Elo (2013) show that smoking differences between blacks and whites at age 50 accounted for 20 and 40 percent of the gap between 1980 and 2005, but not for women. Without adjusting for SES, smoking explains 20 percent of the excessive risk blacks have regarding all-cause mortality.

A study of 720 black smokers from Los Angeles, California showed that 57 percent only smoked menthols, 15 smoked regulars while 28 percent smoked both menthols and regulars (Unger et al, 2010). One of their main findings was that blacks who smoked menthol cigarettes thought that it was a ‘healthier alternative’ to regular cigarettes. Unger et al (2010: 405) also write:

This cross-sectional study identified correlates of menthol smoking, but it does not prove causality. It is possible that smoking menthol cigarettes causes changes in some of the psychological, attitudinal, social, and cultural variables. For example, people who smoke menthols may form beliefs about the positive medicinal benefits of menthols as a way of reducing their cognitive dissonance about smoking.

Figuring out the causation will be interesting, and I’m sure that advertisements outside of storefronts are causally related. Okuyemi et al (2004) also show that blacks who smoke menthol cigarettes are less likely to quit smoking than blacks who smoke regulars. Younger children were more likely to smoke cigarettes with a “longer rod length” (for instance, Newport 100s over Newport regulars). People smoke menthol cigarettes because they taste better, while menthol also “is a prominent design feature used by cigarette manufacturers to attract and retain new, younger smokers.” (Klausner, 2011). Klausner, though, advocates to ban menthol cigarettes, writing:

This evidence suggests that a ban on menthol in cigarettes would result in fewer people smoking cigarettes. Menthol is a prominent design feature used by cigarette manufacturers to attract and retain new, younger smokers. In addition, not only would some current smokers decide to quit rather than smoke non-mentholated cigarettes, but some young people would not make the transition from experimenting with cigarettes to becoming a confirmed smoker. The FDA should ban menthol in cigarettes which will help lower smoking rates particularly among African Americans and women.

Sterling et al (2016) also agree, but argue to ban little cigars and cigarillos (LCCs) writing “Our data add to the body of scientific evidence that supports the FDA’s ban of all characterising flavours in LCCs.” Numerous studies attest to the availability of menthol cigarettes and LCCs which then contributes to influence different demographics to begin smoking. Hersey et al (2006) also shows menthol cigarettes to be a ‘starter product for youth’, stating one reason that children begin smoking mentholated cigarettes is that they are more addictive than non-menthols. Menthol cigarettes are a ‘starter product’ because they taste better than regular cigarettes and, as shown above, seem like they are more ‘theraputic’ due to their taste and coolness compared to regular cigarettes.

Smokers are more likely to be extroverted, tense, anxious and impulsive, while showing more traits of neuroticism and psychoticism than ex- or non-smokers (Rondina, Gorayeb, and Botelho III, 2007). In a ten-year longitudinal study, Zvolensky et al (2015) showed that people who were more likely to be open to experience and be more neurotic would be more likely to smoke, whereas conscientiousness ‘protected’ against picking up the habit. Neuroticism is one of the most important factors of personality to study regarding the habit of smoking. Munafo, Zetteler, and Clark (2006) show in their meta-analysis on personality factors and smoking that neuroticism and increased extraversion were risk factors for being a smoker. I am aware of one study on the effects of different personality and smoking. Choi et al (2017) write:

The results emerging from this study indicate that neuroticism and conscientiousness are associated with the likelihood of being a current smoker, as well as level of ND. Furthermore, personality traits have a greater influence on smoking status and severity of ND in AAs relative to EAs. These relationships were particularly pronounced among smokers with reporting TTFC of ≤5 min.

…

… we found that higher neuroticism and lower conscientiousness were associated with higher likelihood of being a current smoker in the AA sample.

So black smokers were more likely to be conscientious, neurotic and open to experience whereas white smokers were more likely to be neurotic and conscientious.

Finally, racial differences in serum cotnine levels are seen, too. Black smokers have higher levels of cotnine than white smokers (Caraballo et al, 1998; Signorello et al, 2010). Perez-Stable et al (2006) show that higher levels of cotnine can be explained by slower clearance of cotnine along with a higher intake of nicotine per cigarette, because blacks take deeper pulls than whites (though they smoke fewer cigarettes than whites, taking deeper pulls off-sets this; Ho and Elo, 2013).

Smoking can be lessened in all populations—no matter the race/ethincity—with the right universal and intervention efforts (Kandel et al, 2004; Kahende et al, 2011). This can be achieved—especially in low-income areas—by lessening and eventually ridding storefronts of these advertisements for menthol cigarettes, which would then decrease the population of smokers in that area because most only smoke menthols. This would then close some of the black-white mortality gap since smoking causes a good amount of it.

Dauphinee et al (2013) even noted how 52 percent of students recognized Camel cigarettes, whereas 36 percent recognized Marlboro and 32 percent recognized Newports. Black students were three times more likely to recognize Newports than Marlboros (because, in my experience, blacks are way more likely to smoke Newports than Marlboros, which whites are more likely to smoke), while this effect held even after controlling for exposure to smoking by parents and peers. This is yet more proof of the ‘menthol effect’ in lower-income communities that partly drives the higher rates of smoking.

In conclusion, it seems that most of the disparity can be pinned down on Big Tobacco advertising mostly in low-income areas where they spend more than 10 percent of their income on cigarettes. Young children are more likely to know what menthol cigarettes are, what they look like and are more likely to know those type of brains of cigarettes, due mainly to how often and how much they are advertised in low-income areas in comparison to high-income areas. Blacks are also more likely than whites to have the personality traits found in smokers, so this, too, contributes to the how and why of black smoking in comparison to whites; they are more susceptible to it due to their personality along with being exposed to more advertisements since they are more likely to live in lower-income areas than whites.

I don’t believe in banning things, but the literature on this suggests that many people only smoke menthols and that if they were ever banned, most would just quit smoking. I don’t think that we need to go as far as banning menthol cigarettes—or cigarettes in general—we just need to educate people better and, of course, reel in Big Tobaccos reach in lower-income communities. Smoking also began to decline the same year that Joe Camel was ‘voluntarily’ discontinued by its parent company (Pampel and Aguilar, 2008), and so, that is good evidence that at least banning or reforming laws in low-income areas would change the number of smokers in a low-income area, and, along with it, close at least a small part of the black-white mortality gap.

Race/Ethnicity and the Microbiome

1800 words

The microbiome is the number and types of different microorganisms and viruses in the human body. Racial differences are seen everywhere, most notably in the phenotype and morphology. Though, of course, there are unseen racial differences that then effect bodily processes of different races and ethnic groups. The microbiome is one such difference, which is highly heritable (Goodrich et al, 2014; Beaumont et al, 2016; Hall, Tolonen, and Xavier, 2017) (though they use the highly flawed twin method, so heritabilities are most likely substantially lower). They also show that certain genetic variants predispose individuals to microbial dysbiosis. However, diet, antibiotics and birth mode can also influence the diversity of microbiota in your biome (Conlon and Bird, 2015; Bokulich et al, 2017; Singh et al, 2017) and so while the heritability of the microbiome is important (which is probably inflated due to the twin method), diet can and does change the diversity of the biome.

It used to be thought that our bodies contained 90 percent bacteria and only 10 percent human cells (Collen, 2014), however that has been recently debunked and the ratio is 1.3 to 1, human to microbe (Sender, Fuchs, and Milo, 2016). (Collen’s book is still an outstanding introduction to this subject despite the title of her book being incorrect.) Though the 10:1 microbe/human cell dogma is debunked, in no way does that lessen the importance of the microbiome regarding health, disease and longevity.

Lloyd-Price, Abu-Ali, and Huttenhower (2016) review definitions for the ‘healthy human microbiome’ writing “several population-scale studies have documented the ranges and diversity of both taxonomic compositions and functional potentials normally observed in the microbiomes of healthy populations, along with possible driving factors such as geography, diet, and lifestyle.” Studies comparing the biomes of North and South America, Europe and Africa, Korea and Japan, and urban and rural communities in Russia and China have identified numerous different associations that are related to differences in the microbiome between continents that include (but are not limited to) diet, genetics, lifestyle, geography, and early life exposures though none of these factors have been shown to be directly causal regarding geographic microbiome diversity.

Gupta, Paul, and Dutta (2017) question the case of a universal definition of a ‘healthy microbiome’ since it varies by geographic ancestry. Of course, ancestry and geographic location influence culture which influences diet which influences microbiome diversity between populations. This, of course, makes sense. why have a universal healthy microbiome with a reference man that doesn’t reflect the diversity of both the individual and group differences in the microbiome? This will better help different populations with different microbiomes lose weight and better manage diseases in certain populations.

The microbiome of athletes also differs, too. Athletes had enhanced microbiome diversity when compared to non-athletes (Clarke et al, 2016). In a further follow-up study, it was found that microbial diversity correlated with both protein consumption and creatine kinase levels in the body (Clarke et al, 2017) are proxies for exercise, and since they’re all associations, causality remains to be untangled. Nevertheless, these papers are good evidence that both lifestyle and diet leads to changes in the microbiome.

Fortenberry (2013: 165) notes that American racial and ethnic classifications are “social and political in origin and represent little meaningful biologic basis of between-group racial/ ethnic diversity“. It is also known that eating habits, differing lifestyles and metabolic levels also influence the diversity of the microbiome in the three ‘races’* studied (Chen et al, 2016), while deep sequencing of oral microbiota has the ability to classify “African Americans with a 100% sensitivity and 74% specificity and Caucasians with a 50% sensitivity and 91% specificity” (Mason et al, 2014). The infant microbiome, furthermore, is influenced by maternal diet and breastfeeding as well as the infant’s diet (Stearns et al, 2017). This is why differences in race/ethnicity call into question the term of ‘healthy human microbiota’ (Gupta, Paul, and Dutta, 2017). These differences in the microbiome also lead to increased risk for colorectal cancer in black Americans (Goyal et al, 2016; Kinross, 2017).

Further, the healthy vagina “contains one of the most remarkably structured microbial ecosystems, with at least five reproducible community types, or “community state types” (Lloyd-Price, Abu-Ali, and Huttenhower 2016). The diversity of the microbiome in the vagina also varies by race. It was found that 80 percent of Asian women and 90 percent of white women harbored a microbiota species named Lactobacillus, whereas only about 60 percent of ‘Hispanics’ and blacks harbored this species. The pH level, too, varied by race with blacks and ‘Hispanics’ averaging 4.7 and 5.0 and Asians and whites averaging 4.4 and 4.2. So, clearly, since Asians and whites have similar vaginal pH levels, then it is no surprise that they have similar levels of vaginal Lactobacillus, whereas blacks and ‘Hispanics’, with similar pH levels have similar vaginal levels of Lactobacillus.

White subjects also have more diverse species of microbiota than non-white subjects while also having a different microbiota structure (Chen et al, 2015). Caucasian ethnicity/race was also shown to have a lower overall microbiome diversity, but higher Bacteroidetes scores, while white babes also had lower scores of Proteobacteria than black Americans (Sordillo et al, 2017). This comes down to both diet and genetic factors (though causation remains to be untangled).

Differences in the skin microbiome also exist between the US population and South Americans (Blaser et al, 2013). They showed that Venezuelan Indians had a significantly different skin biome when compared to US populations from Colorado and New York, having more Propionibacterium than US residents. Regarding the skin microbiota in the Chinese, Leung, Wilkins, and Lee (2015) write “skin microbiomes within an individual is more similar than that of different co-habiting individuals, which is in turn more similar than individuals living in different households.” Skin microbiota also becomes similar in cohabitating couples (Ross, Doxey, and Neufeld, 2017) and even cohabitating family members and their dogs (Song et al, 2013; Cusco et al, 2017; Torres et al, 2017).

Differences between the East and West exist regarding chronic liver disease, which may come down to diet which may influence the microbiota and along with it, chronic liver disease. (Nakamoto and Schabl, 2016). The interplay between diet, the microbiome and disease is critical if we want to understand racial/ethnic differentials in disease acquisition/mortality, because the microbiome influences so many diseases (Cho and Blaser, 2012; Guinane and Cotter, 2013; Bull and Plummer, 2014; Shoemark and Allen, 2015; Zhang et al, 2015; Shreiner, Kao, and Young, 2016; Young, 2017).

The human microbiome has been called our ‘second genome’ (Zhu, Wang, and Li, 2010; Grice and Seger, 2012) with others calling it an ‘organ’ (Baquero and Nombela, 2012; Clarke et al, 2014; Brown and Hazen, 2015). This ‘organ’, our ‘second genome’ can also influence gene expression (Masotti, 2012; Maurice, Haiser, and Turnbaugh, 2013; Byrd and Seger, 2015) which could also have implications for racial differences in disease acquisition and mortality. This is why the study of the microbiome is so important; since the microbiome can up- and down-regulate gene expression—effectively, turning genes ‘on’ and ‘off’—then understanding the intricacies that influence the microbiome diversity along with the diet that one consumes will help us better understand racial differences in disease acquisition. Diet is a huge factor not only regarding obesity and diabetes differences within and between populations, but a ‘healthy microbiome’ also staves off obesity. This is important. The fact that the diversity of microbiota in our gut can effectively up- and down-regulate genes shows that we can, in effect, influence some of this ourselves by changing our diets, which would then, theoretically, lower disease acquisition and mortality once certain microbiome/diet/disease associations are untangled and shown to be causative.

Finally, the Hadza have some of the best-studied microbiota, and since they still largely live a hunter-gatherer lifestyle, this is an important look at what the diversity of microbiota may have looked like in our hunter-gatherer ancestors (Samuel et al, 2017). The fact that they noticed such diverse changes in the microbiome—some species effectively disappearing during the dry season and reappearing during the wet season—is good proof that what drives these changes in the diversity of the microbiota in the Hadza are seasonal changes in diet which are driven by the wet and dry seasons.

Gut microbiota may also influence our mood and behavior, and it would be interesting to see which types of microbiota differ between populations and how they would be associated with certain behaviors. The microbes are a part of the unconscious system which regulates behavior, which may have causal effects regarding cognition, behavioral patterns, and social interaction and stress management; this too makes up our ‘collective unconscious’ (Dinan et al, 2015). It is clear that the microbes in our gut influence our behavior, and it even may be possible to ‘shape our second genome’ (Foster, 2013). Endocrine and neurocrine pathways may also be involved in gut-microbiota-to-brain-signaling, which can then alter the composition of the microbiome and along with it behavior (Mayer, Tillisch, and Gupta, 2015). Gut microbiota also plays a role in the acquisition of eating disorders, and identifying the specific microbiotal profiles linked to eating disorders, why it occurs and what happens while the microbiome is out of whack is important in understanding our behavior, because the gut microbiome also influences our behavior to a great degree.

The debate on whether or not racial/ethnic differences in microbiome diversity differs due to ‘nature’ or ‘nurture’ (a false dichotomy in the view of developmental systems theory) remains to be settled (Gupta, Paul, and Dutta, 2017). However, like with all traits/variations in traits, it is due to a complex interaction of the developmental system in question along with how it interacts with its environment. Understanding these complex disease/gene/environment/microbiotal pathways will be a challenge, as will untangling direct causation and what role diet plays regarding the disease/microbiota/dysbiosis factor. As we better understand our ‘second genome’, our ‘other organ’, and individual differences in the genome and how those genomic differences interact with different environments, we will then be able to give better care to both races/ethnies along with individuals. Just like with race and medicine—although there is good correlative data—we should not jump to quick conclusions based on these studies on disease, diet, and microbiotal diversity.

The study of ethnic/racial/geographic/cultural/SES differences in the diversity of the microbiome and how it influences disease, behaviors and gene expression will be interesting to follow in the next couple of years. I think that there will be considerable ‘genetic’ (i.e., differences out of the womb; I am aware that untangling ‘genetic’ and ‘environmental’ in utero factors is hard, next to impossible) differences between populations regarding newborn children, and I am sure that even the microbiota will be found to influence our food choices in the seas of our obesogenic environments. The fact that our microbiota is changeable with diet means that, in effect, we can have small control over certain parts of our gene expression which may then have consequences for future generations of our offspring. Nevertheless, things such as that remain to be uncovered but I bet more interesting things never dreamed of will be found as we look into the hows and whys of both individual and populational differences in the microbiome.

You Don’t Need Genes to Delineate Race

2100 words

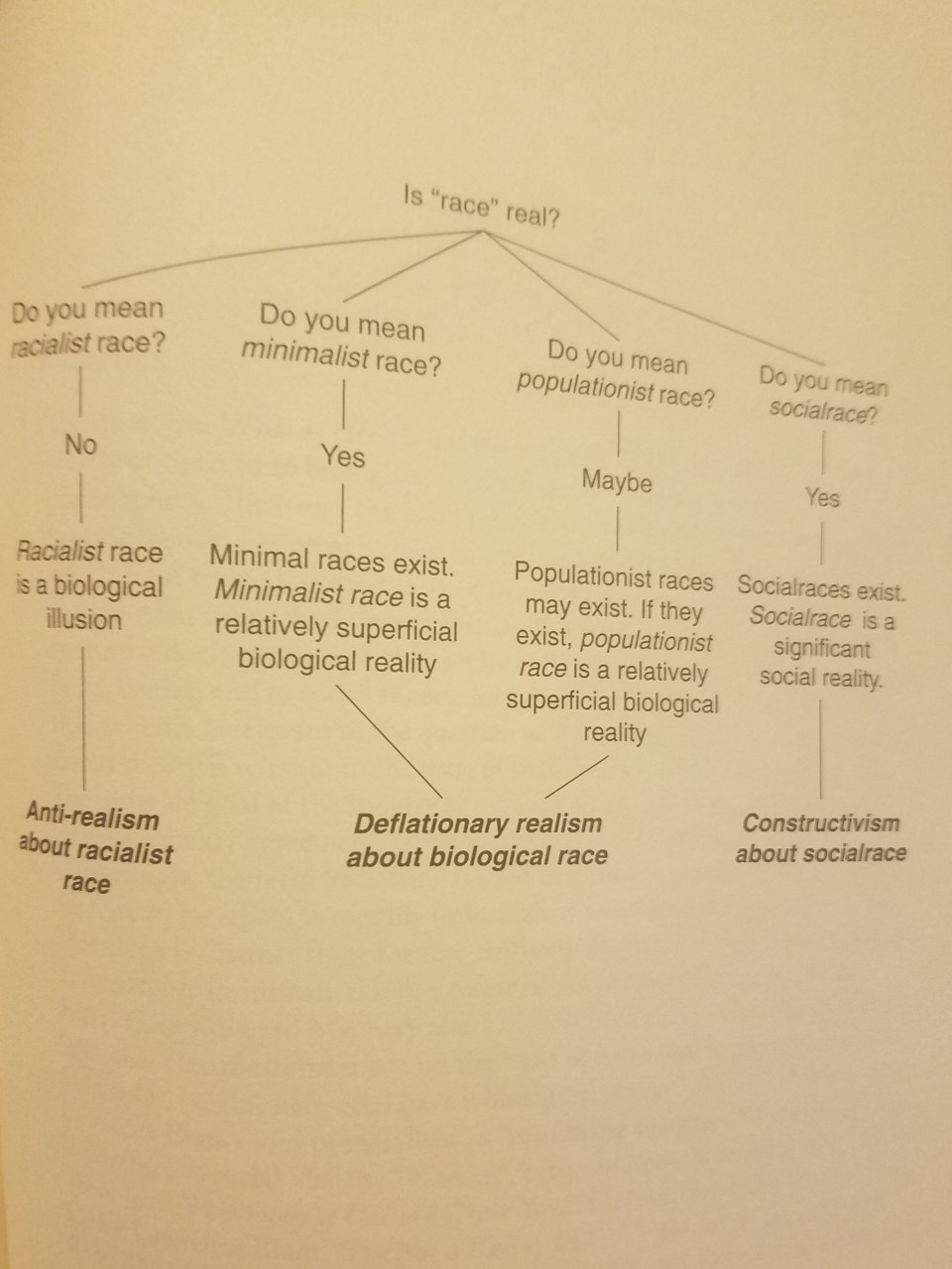

Most race deniers say that race isn’t real because, as Lewontin (1972) and Rosenberg (2002) state, the within-group variation is larger than the between-group variation. Though, you can circumvent this claim by not even looking at genes/allele frequencies between races, you can show that race is real by looking at morphology, phenotype and geographic ancestry. This is one of Michael Hardimon’s race categories, the minimalist concept of race. This concept does not entail anything that we cannot physically ‘see’ with our eyes (e.g., mental and psychological traits are off the table). Using these concepts laid out by Hardimon can and does prove that race is real and useful without even arguing about any potential mental and psychological differences between human races.

Morphology

Morphology is one of the most simple tells for racial classification. Just by looking at average morphology between the races we can use attempt to use this data point as a premise in the argument that races exist.

East Asians are shorter with shorter limbs and have an endomorphic somatype. This is due to evolving in cold climate, as a smaller body and less surface area can be warmer much quicker than a larger body. This is a great example of Allen’s rule: that animals in colder climates will be smaller than animals in warmer climates. Using average morphology, of course, can show how the population in question evolved and where they evolved.

Regarding Europeans, they have an endomorphic somatype as well. This, again, is due to where they evolved. Morphology can tell us a lot about the evolution of a species. Though, East Asians and Europeans have similar morphologies due to evolving in similar climates. Like East Asians, Europeans have a wider pelvis in comparison to Africans, so this is yet another morphological variable we can use to show that race exists.

Finally, the largest group is ‘Africans’ who have the largest phenotypic and genetic diversity on earth. Generally, you can say that they’re tall, have long limbs and a short torso, which is due to evolving in the tropics. Furthermore, and perhaps most important, Africans have narrower pelves than East Asians and Europeans. This character is one of the most important regarding the reality of race because it’s one of the most noticeable, and we do notice in when it comes to sports competition because that certain type of morphology is conducive to athletic success. (Also read my recent article on strength and race and my article on somatype and race for more information on morphologic racial differences.)

Phenotype

Morphology is a part of the phenotype too, obviously, but there is a reason why it’s separated. As is true with morphology, different characters evolved due to cultural evolution (whether or not they adopted farming early) or evolution through natural selection, drift and mutation. Though, of course, favorable mutations in a certain environment will be passed on and eventually become a part of the characteristics of the population in question.

East Asians have the epicanthic fold, which probably evolved to protect the eye from the elements and UV rays on the Mongolian steppes. They also have softer features than Europeans and Africans, but this is not due to lower testosterone as is popularly stated. (Amusingly enough, there is a paper that stated that East Asians have Down Syndrome-like qualities due to their epicanthic folds to bring up one reason.) Even then, what some races find attractive or not can show how and why certain facial phenotypes evolved. To quote Gau et al (2018):

Compared with White women, East Asian women prefer a small, delicate and less robust face, lower position of double eyelid, more obtuse nasofrontal angle, rounder nose tip, smaller tip projection and slightly more protruded mandibular profile.

And they conclude:

The average faces are different from the attractive faces, while attractive faces differ according to race. In other words, the average facial and aesthetic criteria are different. We should use the attractive faces of a race to study that races aesthetic criteria.

We can use studies such as this to discern different facial phenotypes, which, again, proves that race exists.

The climate one’s ancestors evolved in dictates nose shape. In areas where it is extremely dry and also has a lot of heat, a larger mucous area is required to moisten inspired (inhaled) air, which is why a more flat and narrow nose is needed.

Zaidi et al (2017) write:

We find that width of the nares is correlated with temperature and absolute humidity, but not with relative humidity. We conclude that some aspects of nose shape may have indeed been driven by local adaptation to climate.

Though climate, of course, isn’t the only reason for differences in nose shape; sexual selection plays a part too, as seen in the above citation on facial preferences in East Asian and European women.

There are also differences in hirsutism between the races. Racial differences exist regarding upper lip hair, along with within-race differences (Javorsky et al, 2014). The self-reported races of African American, East Asian, Asian Indian, and ‘Hispanic’ predicted facial hair differences in women, but not how light their skin was. The women were from Los Angeles, USA; Rome, Italy; Akita, Japan; and London, England. Indian women had more hair than any other race, while European women had the least. Regarding within-race variation, Italian women had more hair on their upper lip than American and British women. Skin lightness was related to hair on the upper lip. (Also read my article The Evolution of Human Skin Variation for more information on racial differences in skin color.)

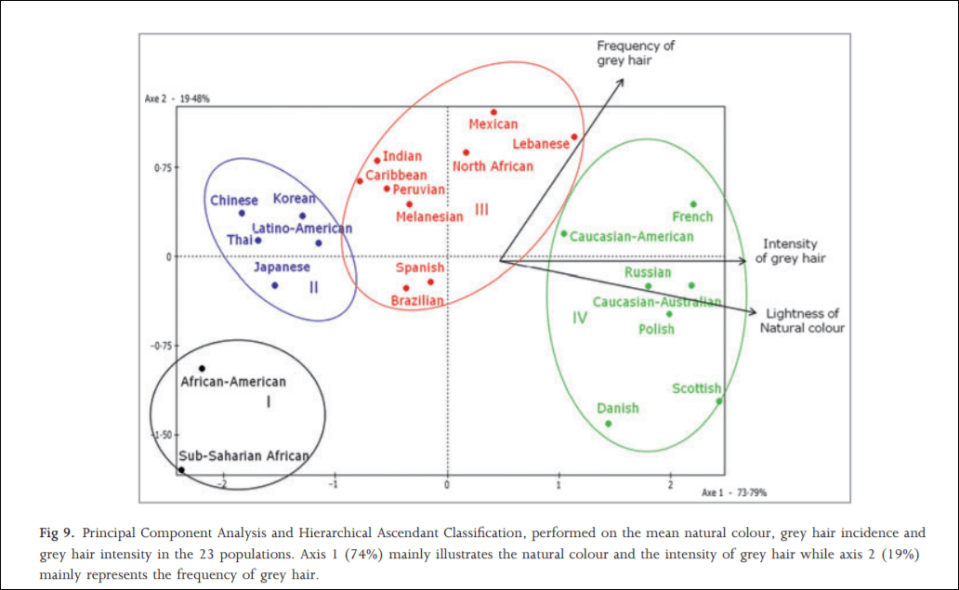

In 2012, an interesting study was carried out on hair greying on a sample population of a large number of the world’s ethnies titled Greying of the human hair: a worldwide survey, revisiting the ‘50’ rule of thumb. The objective of the study was to test the ’50-50-50′ rule; that at age 50, 50 percent of the population has at least 50 percent of their hair grey. Africans and Asians showed fewer grey hairs than whites who showed the most. The results imply that hair greyness varies by ethnicity/geographic origin, which is perfect for the argument laid out in this article. The global range for people over 50 with 50 percent or more of their hair grey was between 6 and 23 percent, far lower than what was originally hypothesized (Panhard, Lozano, and Loussouarn, 2012). They write on page 870:

With regard to the intensity of hair greying, the lowest values were found among African and Asian groups, especially Thai and Chinese, whereas the highest values were in subjects with the blondest hair (Polish, Scottish, Russian, Danish, CaucasianAustralian and French).

…

Altogether, these analyses clearly illustrate that the lowest incidences and intensities of grey hair are found in populations of the darkest hair whereas the highest intensities are found in populations with the lightest hair tones.

Actual hair diversity is much more concentrated in Europeans, however (Frost, 2005). (See Peter Frost’s article Why Do Europeans Have So Many Hair and Eye Colors?) It is largely due to sexual selection, with a few climatic factors thrown in. Dark hair, on the other hand, is a dominant trait, which is found all over the world.

Zhuang et al (2010) found significant differences in facial morphology between the races, writing:

African-Americans have statistically shorter, wider, and shallower noses than Caucasians. Hispanic workers have 14 facial features that are significantly larger than Caucasians, while their nose protrusion, height, and head length are significantly shorter. The other ethnic group was composed primarily of Asian subjects and has statistically different dimensions from Caucasians for 16 anthropometric values.

…

Statistically significant differences in facial anthropometric dimensions (P < 0.05) were noted between males and females, all racial/ethnic groups, and the subjects who were at least 45 years old when compared to workers between 18 and 29 years of age.

Blacks had statistically significant differences in lip and face length when compared to whites (whites had shorted lips than blacks who had longer lips than whites).

Brain size and cranial morphology, too, differs by geographic ancestry which is directly related to the climate where that population evolved (Beals, Smith, and Dodd, 1984). Most every trait that humans have—on average of course—differs by geographic location and the cause of this is evolution in these locations along with being a geographically isolated breeding population.

Geographic ancestry

The final piece to this argument is using where one’s recent ancestors came from. There are five major populations from a few geographic locales: Oceania, the Americas (‘Native Americans), Europe, Africa and East Asia. These geographic locales have peoples that evolved there and underwent different selective pressures due to their environment and their bodies evolved to better suit their environment, and so racial differences in morphology and phenotype occurred so the peoples could survive better in that location. No one part of this argument is more important than any other, though geographic ancestry is the final piece of the puzzle that brings everything together. Because race is correlated with morphology and phenotype, the geographic ancestry dictates what these characteristics look like.

Conclusion

Thus, this is the basic argument:

P1: Differing populations have differing phenotypes, including (but not limited to) facial structure, hair type/color, lip structure, skull size, brain size etc.

P2: Differing populations have differing morphology which, along with this population’s phenotype, evolved in response to climatic demands along with sexual selection.

P3: This population must originate from a distinct geographic location.

C: If all three of the above premises are true, then race—in the minimalist sense—exists and is biologically real.

This argument is extremely simple, and along with the papers cited above in support of the three premises and the ultimate conclusion, it will be extremely hard for race deniers to counter. We can say that P1 is logically sound because geographically isolated populations differ in the above-mentioned criteria. We can say that P2 is logically sound since differing populations have differing morphology (as I have discussed numerous times which leads to racial differences in sporting competition) such as differing trunk lengths, leg lengths, arm lengths and heights which are largely due to evolution in differing climates. We can say that P3 is logically sound because the populations that would satisfy P1 and P2 do come from geographically distinct locations; that is, they have a peculiar ancestry that they only share.

This concept of minimalist race from Michael Hardimon is (his) the racialist concept of race “stripped down to its barest bones” (Hardimon, 2017: 3). The minimalist concept of race, then, does not discuss any differences between populations that cannot be directly discerned with the naked eye. (Note: You can also use the above arguments/data laid out for the populationist concept of race, which, according to Hardimon (2017: 3) is: “A nonracialist (nonessentialist, nonhierarchical) candidate scientific concept that characterizes races as groups of populations belonging to biological lines of descent, distinguished by patterns of phenotypic differences, that trace back to geographically separated and extrinsically reproductively isolated founder populations.)

Minimalist race is biologically sound, grounded in genetics (though I have argued here that you don’t need genetics to define race), and is grounded in biology. Minimalist race is defined as characteristics of the group, not of the individual. Minimalist race are biologically real. Minimalist races exist because, as shown with the data presented in this article, phenotypic and morphologic traits are unevenly distributed throughout the world which then correlates with geographic ancestry. It cannot get any more simpler than that: race exists because differences in phenotype and morphology exist which then corresponds with geographic ancestry.

From Hardimon (2017: 177)\

No sane or logical person would deny the existence of race based on the criteria laid out in this article. We can also make another leap in logic and state that since minimalist races exist and are biologically real then geographic ancestry should be a guide when dealing with medicine and different minimalist races.

It is clear that race exists in the minimal sense; you do not need genes to show that race is real, nor that race has any utility in a medical context. This is important for race deniers to understand: genes are irrelevant when talking about the reality of race; you only need to just use your eyes and you’ll see that certain morphologies and phenotypes are distributed across geographic locations. It is also very easy to get someone to admit that races exist in this minimalist-biological sense. No one denies the existence of Africans, Europeans, ‘Native’ Indians, East Asians and Pacific Islanders. These populations differ in morphology and other physical characters which are unevenly distributed by geographic ancestry, so, therefore: minimialist races exist and are a biological reality.

Malaria, the Sickle Cell Trait, and Fast Twitch Muscle Fibers

2550 words

West Africans and their descendants have longer limbs and a shorter trunk than Europeans, on average—as I have extensively noted. Due to where they evolved, of course, they have a different morphology and physiology. Bergmann’s rule states that peoples with recent ancestry in the tropics will have slimmer pelvic bones and be narrower overall whereas Allen’s rule states that peoples with recent ancestry in the tropics will have long limbs, these traits being good for heat dissipation (Lieberman, 2015) and is one reason why West Africans and their descendants excel in these most sports in America.

The fact that a lot of African ethnic groups have different anatomic proportions and physiologic adaptations in comparison to people who have evolved in non-tropical climates is not contested. Morrison and Cooper’s (2006) hypothesis on sick cell anemia driving elite athletic performance in West Africans and their descendants is one of the most interesting explanations I’ve heard on the biochemical differences between the races. Sickle cell anemia is caused by a gene mutation. On amino acid 6, a single nucleotide substitution from A to T (As pair it Ts, Gs pair with Cs). This substitution changes a glutamic acid codon to valine codon which then causes sickling of the blood. Sickle cell anemia, of course, is not a ‘black disease’ as is popularly believed, but it, in fact, has to do with geography and the prevalence of malaria-carrying mosquitoes in that location. “This mutation“, Morrison and Cooper (2006) write “appears to have triggered a series of physiological adjustments, which have had favourable athletic consequences.”

Now, I’m aware that those who are already skeptical of this hypothesis may say ‘so does this mean that Italians, Greeks, MENA peoples etc have more type II fibers and would excel in these competitions?’, no it does not mean that because they don’t have the requisite morphology that West Africans have.

In the 1970s, a study was carried out on the physiological and anatomical proportions of Olympic athletes who competed in the 1968 Olympic games. Anatomic and physiologic measures were taken for each athlete. They used four racial classifications: Negroid, Caucasoid, Mongoloid, and mestizo (Indian/Spanish mix). The classifications were based on “were based on identification and somatotype photographs, as well as physical characteristics including skin color; general body shape; proportions of segments of the limbs; facial structure; form of eyes, lips, and nose; and colour and texture of hair” (Morrison and Cooper, 2006). This study, of course, also confirmed the anatomic differences between blacks and other races and how it leads to superior sports performance. Though, something peculiar was noted in the black athletes. Morrison and Cooper (2006) write: “Although the study failed to link athletic capability to a single gene system, the authors expressed “surprise” that “a sizeable number of Negroid Olympic athletes manifested the sickle-cell trait.””

One interesting study looked at the sickle cell trait (SCT) in French West Indian elite sprint athletes (Marlin et al, 2005). Using the French National Team for the year 2000, Marlin et al (2005) identified 3 sprinters (2 males and 1 female) who tested positive for the SCT. They also noticed a significantly higher presence of titles for people who tested positive for the SCT (38.6 percent for males and 50 percent for females. Marlin et al (2005: 624) conclude “that male SCT carriers are able to perform sprints and brief exercises at the highest levels” and “that brief and intensive exercise performance involving mainly alactic anaerobic metabolism may be enhanced by HbS in elite male sprinters.”

Blacks had narrower hips, longer arms and legs and a shorter trunk in comparison to other races. Of course, somatype is the variable that matters here but certain races are more likely to have certain anatomic characters that lead to superior spots performance on comparison to other races. The authors also attempted to link traits with single gene networks but were unsuccessful. However, they did notice that a large number of black athletes tested positive for the sickle cell trait. There is a conundrum here, however. People with the sickle cell gene might have a greater oxygen demand which causes more in vivo cell sickling. It was hypothesized that these individuals would be at a disadvantage since the 1968 Olympic games were held in Mexico city which is a high altitude area. They theorized that their blood would sickle more at the high altitude in comparison to low altitude but this was not seen.

Then another study was carried out which showed that not only do individuals with the sickle cell trait have lower hemoglobin levels, but all blacks do (Garn, Smith, and Clark, 1975). This is how and why they can perform at high altitudes despite having the sickle cell trait. Then, to test if this was mostly ‘environmental’ or ‘genetic’ they undertook a large study where they followed individuals throughout their whole lives and the difference persisted even later in life. Of course, according to other authors, some sort of compensatory mechanism should exist to counteract black’s lower hemoglobin levels, since this deficiency even exists in athletes (Morrison and Cooper, 2006).

As I’ve written about in the past, it was established that type I and type II fibers use different metabolic pathways and that type II fibers lead to improved athletic performance (along with the certain genotype for the ACTN3 gene). Morrison and Cooper (2006) also state that, of course, not all West Africans and descendants have this trait, and that these people came from a small area of West Africa.

A study looking at pulmonary differences between blacks and whites was conducted which found that blacks compensated for smaller lungs by breathing harder than whites while engaged in physical activity. In a study of 80 Asians and Europeans, Korotzer, Ong, and Hansen (2000) also showed that Asians had lower pulmonary functioning than Europeans. Even differences in chest size has been purported to explain differences in lung functioning, though this relationship did not hold (Whittaker, Sutton, and Beardsmore, 2005). Though, in his short review on race and the history of lung functioning, Braun (2015) writes that “At the very least, the idea that people labelled ‘white’ naturally have higher lung capacity than other races throughout the world should be approached with some skepticism.” because “Most commercially available spirometers internationally ‘correct’ or ‘adjust’ for race in one of two ways: by using a scaling factor for all people not considered to be ‘white’; or by applying population-specific norms. To enable the spirometer, the operator must select the race of an individual, as well as indicate their age, sex/gender and height. How race (or population) is determined varies, with most operators either asking patients to self-identify or ‘eyeballing it’. Interviews with users of the spirometer indicate that many operators are unaware that they are automatically activating race correction when they select a patient’s race (3). Because ‘correction’ is programmed into the spirometer by the manufacturer, it can be difficult to disable.”

Braun, Wolfgang, and Dickerson (2013) and Braun (2015) critiques pulmonary studies because in a large majority of cases, possible explanatory variables for lower lung functioning in black Americans could be related to SES. Harik-Khan, Muller, and Wise (2004) used participants from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. They chose black and white children between the ages of 8 and 17 who did not smoke (n=1462, 623 whites and 839 blacks). Blacks were taller but had lower SES, had lower levels of vitamins A and C, along with lower levels of alpha carotene. They also had lower lung functioning. When they adjusted for confounds, sitting explained 42 to 53 percent of the racial difference, SES factors and antioxidant vitamin levels accounted for 7 to 10 percent of the difference. So they could only account for 50 to 63 percent of the difference. In 752 children aged 8 to 10 years of age, low birth weight accounted for 3 to 5 percent of the differences whereas maternal smoking had no effect (Harik-Khan, Muller, and Wise, 2004). So the remaining variation, obviously, will be accounted for by other SES variables, biology, or environmental factors.

Whitrow and Harding (2004) show that, at least for Caribbean blacks living in the UK, upper body differences explained most of the variation in lung functioning than did sitting height, with social correlates having a small but significant impact.

So because blacks have more type II fibers on average, they will convert glucose into energy more rapidly than whites. The energy for these muscle contractions comes from adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Blacks and whites both convert glucose into ATP for cellular functioning but in different ratios. These differences in muscular contractions driven by the metabolic pathway differences of the fibers are one large reason why blacks dominate sports.

Fibers are broken down into two types: fast and slow twitch. Slow twitch fibers use aerobic metabolism which is how they generate ATP and greater oxidative capacity due to higher levels for myoglobin. Oxygen bound to hemoglobin is carried to the red blood cells through capillaries that then influence muscular performance. Myoglobin is also essential for the transport of oxygen to the mitochondria where it is then consumed. Conversely, fast twitch fibers use anaerobic metabolism, have less oxidative capacity, less myoglobin and due to this, they are more dependent on anaerobic metabolism. Blacks also have “significantly higher levels of activity in their phosphagenic, glycolytic, and lactate dehydrogenase marbling pathways than their Caucasian counterparts” (Morrison and Cooper, 2006). This is where the production of ATP is regenerated,and so they have a huge advantage here. So higher faster production of ATP lead to more efficient ATP production, too. However when the ATP is depleted then it’s replaced by a reaction that depletes creatine phosphate. Skeletal muscle then converts “chemical energy into mechanical work” which only 30 to 50 percent is wasted as heat, so even small physiological differences can lead to large differences in performance (Morris and Cooper, 2006).

Though that’s not the only biochemical difference (faster ATP regeneration and production) between the blacks and whites that would explain sports performance. Morrison and Cooper (2006) write: “There is also considerably greater activity in the lactate dehydrogenase pathway of people of West African descent. A primary function of this pathway is to reduce muscle fatigue by converting lactic acid back to glucose and refeeding the muscles. This cyclic set of reactions, from muscles to liver and back to muscles, is known as the Cori cycle.”

Lactic acid production is that feeling in your muscles when during extended athletic activity whereas the postponement of muscle fatigue rests on the rate at which lactic acid is covered into glucose. The rate of this removal is further increased by the lactate dehydrogenase pathway describe above by Morrison and Cooper.

Clearly, the production of lactic acid causes problems during physical activity. The production of lactic acid into glucose to refers the muscles through the lactate dehydrogenase pathway is critical, for if glycogen reserves are depleted during extended physical activity then blood glucose would become the primary source of energy for the muscles, which could lead to lowered blood glucose levels and the nervous system may become compromised. During prolonged activity, however, if glucose isn’t available for energy then the body uses fat reserves which is less efficient than carbohydrates for energy and combustion.

Morrison and Cooper conclude: “Not the least of coincidence seems to be the influence of the compensatory sickle cell gene on oxygen transport and availability to the tissues. The reduced availability pulled with reduced oxygen myoglobin in the preponderant fast-twitch muscle fibres which are adapted for rapid anaerobic energy (ATP) regeneration, all give a new outcome of muscle anatomical and biochemical advantages which proffer a superior athleticism.”

Though, at the moment, as David Epstein states in his 2014 book The Sports Gene: Inside the Science of Extraordinary Athletic Performance, in a few studies done on mice genetically altered to have low hemoglobin levels, a there was a “shift of type IIa fast-twitch muscle fibers to type IIb “super fast twitch” muscle fibers in their lower legs” (Epstein, 2014: 179). This is also a developmental effect of mice in their lifetime, not a direct effect of evolution (Epstein, 2014: 179). No compensatory mechanism yet exists for humans, which I will attempt to untangle in future articles on the matter.

At the end of the chapter on this subject (Chapter 11, Malaria and Muscle Fibers, page 179), Epstein states that he asked physiologists their thoughts on the hypothesis. A few people approved of it, whereas one stated that he had evidence for physiological differences between blacks and whites that have not been studied before but he won’t release his results:

Several scientists I spoke to about the theory insisted they woud have no interest in investigating it because of the inevitably thorny issue of race involved. On of them told me that he actually has data on ethnic differences with respect to a particular physiological trait, but that he would never publish the data because of potential controversy. Another told me he would worry about following Cooper and Morrison’s line of inquiry because any suggestion of a physical advantage among a group of people could be equated to a corresponding lack of intellect, as if athleticism and intelligence were on some kind of biological teeter-totter. With that stigman in mind, perhaps the most important writing Cooper did in Black Superman [Cooper’s book] was his methodical eviseceration of any supposed inverse link between physical and mental prowess. “The concept that physical superiority could somehow be a symptomn of intellectual inferiority only developed when physical superiority became associated with African Americans,” Cooper wrote. “That association did not begin until about 1936.” The idea that athleticism was suddenly inversely proportional to intellect was never a cause of bigotry, but rather a result of it. And Cooper implied a more serious scientific inquiry into difficult issues, not less, is the appropriate path. (Epstein, 2014: 179) [Entine (2002) also spends a considerable amount of time debunking the myth of intelligence and athletic ability being negatively correlated in his 2002 book Taboo: Why Black Athletes Dominate Sports and Why We’re Afraid to Talk About It, which was kind of popularized by Rushton (1997) with his now debunked r/K selection theory.]

Things like this piss me off. These differences are actually measurable and lead to trait differences between the races, and know the mechanisms, pathways and whatnot and people are still. Scared to share their findings. One day, I hope, science will find a way to disregard people’s feelings in regard to people’s feelings on notable, testable and replicable differences between the races, most importantly between blacks and whites. I’ve noted how type II fibers lead to metabolic changes and small tears which then cause big problems. This is due to how fast the type II fibers fire in comparison to the slow twitch fibers.

This hypothesis is extremely interesting and now that I’ve laid out Morrison and Cooper’s (2006) hypothesis, I’m going to take a deep dive into this literature to see what I can prove about this hypothesis. Of course, the somatype along with the fiber distribution matters, as does having the XX genotype and not RR, which lends to superior athletic performance when coupled with type II muscle fibers (Broos et al, 2016). The pieces of this puzzle are, in my opinion, slowly being put together for someone to come along and integrate them into a coherent theory for the sickle cell trait and superior athletic performance through type II muscle fibers. It’s very interesting to note that elite sprinters were more likely to carry the SCT and that champion sprinters were more likely to have it too.

Race and Strength on the Big Four Lifts

2450 words

Different races have different morphology/somatype. Therefore, we can reason that different races would fare better or worse at a certain lift depending on their limb length, such as leg length, arm length, torso length and so on. How do somatypic differences lead to differences in strength between the races on the Big Four lifts? The four lifts I will cover are bench press, deadlift, squat and overhead press.

Squat

East Asians

East Asians have higher levels of body fat (for instance the Chinese, Wang et al, 2011) and have lower BMIs, yet higher levels of body fat (Wang et al, 1994). This, along with their somatype are part of the reason why they excel in some strength sports. Since East Asians have a smaller stature, averaging about 5 feet 8 inches, with shorter arms and legs. Thinking about how the ancestors of the East Asians evolved, this makes sense: they would have needed to be shorter and have shorter limbs as it is easier to warm a body with a smaller surface area. Therefore, while squatting they have a shorter path to travel with the bar on their back. East Asians would strongly excel at the squat, and if you watch these types of competitions, you’d see them strongly overrepresented—especially the Chinese.

African-Americans

African-Americans are descended from West African slaves, and so they have longer, thinner limbs with lower amounts of body fat on average (especially if they have more African ancestry), which is a classic sign of a mesomorphic phenotype. They do also skew ecto, which is useful in the running competitions they dominate (in the case of West Africans and descendants and certain tribes of Kenyans and Ethiopians). Either way, due to their long limbs and a short torso, they have to travel further with the weight therefore here they suffer and wouldn’t be as strong as people who have a long torso with shorter limbs.

European Americans

Like East Asians, Europeans have similar morphology—skewing ectomorphic, the somatype that dominates strength competitions. Having a long torso with shorter limbs and more type I than type II fibers, they would then be able to lift more, especially since these competitors keep a high body fat percentage. Again, like with East Asians, there is a biomechanical advantage here and due to their higher levels of body fat and endomorphic somatype along with shorter limbs, they would be able to move more weight on the squat, especially more than African-Americans. Biomechanics is key when it comes to evaluating different groups’ morphology when attempting to see who would be stronger on average.

Deadlift

East Asians

The deadlift is pretty straightforward: bending down and deadlifting the weight off of the ground. Key anatomic differences between the races dictate who would be better here. East Asians, with shorter limbs and a longer torso the bar has to travel a further path, compared to someone with longer limbs and shorter torso. Though, someone with short limbs and a short torso would also have a biomechanical advantage in pulling, it is nothing like if one has long arms and a short torso.

African-Americans

Here is where they would shine. Their anatomy is perfect for this lift. Since they have longer limbs and a shorter torso, the bar has a shorter path to travel to reach the endpoint of the lift. At the set-up of the lift, they already have a biomechanical advantage and they can generate more power in the lift due to their leverage advantage. The deadlift favors people with a long torso, short femurs, and long arms, and so it would favor African-Americans. (Their long arms off-sets their short torsos, though the bar would still have to travel further, they still would have the ability to move more weight.)

European Americans

European Americans would have the same biomechanical problems as East Asians, but not as much since they have a taller stature. It is well-known in the world of weightlifting that having shorter, ‘T-rex arms’ impedes strength on the lift, since speaking from an anatomic viewpoint, they are just not built for it. No style of deadlift (the sumo or conventional) suits people with short arms, and so they are already at a biomechanical disadvantage. Relative to African-Americans, European Americans have ‘T-rex arms’ and therefore they would suffer at pulling exercises—deadlift included.

Overhead press

East Asians

The overhead press is where people with shorter arms would excel. Thus, East Asians would be extremely strong pushers. Say the bar starts at the top of their chest, the path of the bar to the lockout would be shorter than if someone had longer arms. The size of the trapezius muscles also comes into play here, and people with larger trapezius muscles have a stronger press. The East Asians short stature and therefore shorter limbs is perfect for this lift and why they would excel.

African-Americans

African-Americans would suffer at the overhead press for one reason: their long limbs, mainly their arms. The bar has a further path to travel and thus strength would be impeded. Indeed, people not built for pressing have long arms, long torsos, and long legs. Performing the full range of motion, African-Americans would have less strength than East Asians and European Americans.

European Americans

Again, due to similar morphology as East Asians, they, too, would excel at this lift. Since the lift is completed when the arms lock out, those with shorter arms would be able to move more weight and so what hurts them on the deadlift helps on pressing movements like the overhead press.

Bench press

East Asians

Lastly, the bench press. East Asians would excel here as well since they have shorter arms and the bar would have a shorter path to travel. Notice anything with bar movement? That’s a key to see which group would be stronger on average: looking at the average morphology of the races and then thinking about how the lift is performed, you can estimate who would be good at which lift and why. The bench press would favor someone with a shorter stature and arms, and they’d be able to lift more weight. (I personally have long arms compared to my body and my bench press suffers compared to my deadlift.) However, Caruso et al (2012) found that body mass is a more important predictor of who would excel at the bench press. East Asians have a higher body fat percentage, and therefore would be stronger on average in the lift.

African Americans

Here, too, African-Americans will suffer. Like with the overhead press, the bar has a further path to travel. They also have less body fat on average and that would also have the bar travel more, having the individual put more exertion into the lift compared to someone who had shorter arms. The longer your arms are in a pushing exercise, the further the bar has to travel until lockout. Thus you can see that people with longer arms would suffer in the strength department compared to people with shorter arms, but this is reversed for pulling exercises like the deadlift described above. (There is also a specific longitudinal study on black-white differences in bench press which I will cover in the ‘Objections‘ section.)

European Americans

Again, like with East Asians due to similar somatype, European Americans, too, would excel at this lift. They are able to generate more pound-for-pound power in the lift. The bar also has a shorter path to travel and since the people who compete in these competitions also have higher levels of body fat, then the bar has less of a distance to travel, thus increasing the amount of force the muscle can generate. Limb size/body mass/somatype predict how races/individuals would do on specific lifts.

Objections

One of the main objections that some may have is that one longitudinal study on black and white police officers found that blacks were stronger than whites at the end of the study (Boyce et al, 2014). However, I heavily criticized this paper at the beginning of the year and for good reason: heights of the officers weren’t reported (which is not the fault of the researchers but of an ongoing lawsuit at that department since people complained that they were discriminating against people based on height). The paper is highly flawed, but looking at it on face value someone who does not have the requisite knowledge they would accept the paper’s conclusions at face value. One of the main reasons for my criticism of the paper is that the bench press was tested on a Smith machine, not a barbell bench press. Bench pressing on the Smith machine decreases stability in the biceps brachii (Saterbakken et al, 2011) but there is similar muscle recovery between different bench presses in trained men (Smith, barbell, and dumbbell) (Ferreira et al, 2016). This does not affect my overall critique of Boyce et al (2014) however, since you can move more weight than you would normally be able to, along with the machine being on one plane of motion so everyone has to attempt to get into the same position to do the lift and we know how that is ridiculous due to individual differences in morphology.

Some may point to hand-grip tests, which I have written about in the past, and state that ‘blacks are stronger’ based on hand-grip tests. Just by looking at the raw numbers you’d say that blacks had a stronger grip. However, to get an idea of the strength differences pound-for-pound there is a simple formula: weight lifted/bodyweight=how strong one is pound-for-pound on a certain exercise. So using the values from Araujo et al (2010), for blacks we have a grip strength of 89.826 with an average weight of 193 pounds. Therefore pound-for-pound strength comes out to .456. On the other hand, for Europeans, they had an average grip strength of 88.528 pounds with an average weight of 196 pounds, so their pound-for-pound grip strength is about .452, which, just like African-Americans is almost half of their body weight. One must also keep in mind that these hand-grip studies are done on older populations. I have yet to come across any studies on younger populations that use the big four lifts described in this article and seeing who is stronger, so inferences are all that we have.

Further, Thorpe et al (2016) also show how there is an association between household income and grip-strength—people who live in homes with higher incomes have a stronger grip, with blacks having a stronger grip than whites. Thorpe et al (2016) showed that black women had a stronger grip strength than white women, whereas for black men they only had a stronger grip than white men at the highest SES percentile. This could imply nutrient deficiencies driving down their ability for increases grip strength, which is a viable hypothesis. Although Thorpe et al (2016) showed that black men had a stronger grip strength, these results conflict with Haas, Krueger, and Rohlfson (2012) though the disparities can be explained by the age of both cohorts.

Nevertheless, grip strength—as well as overall strength—is related to a higher life expectancy (Ruiz et al, 2008; Volkalis, Haille, and Meisinger, 2015). If blacks were stronger—and this is being debated with studies like hand-grip—then we should expect to see black men living longer than white men, however, we see the opposite. Black men die earlier than white men, and it just so happens that the diseases that are correlated with strength and mortality are diseases that blacks are more likely to get over whites. One should think about this if they’re entertaining the idea that blacks have an inherent strength advantage over whites.