Don’t Fall for Facial ‘Reconstructions’

1400 words

Back in April of last year, I wrote an article on the problems with facial ‘reconstructions’ and why, for instance, Mitochondrial Eve probably didn’t look like that. Now, recently, ‘reconstructions’ of Nariokotome boy and Neanderthals. The ‘reconstructors’, of course, have no idea what the soft tissue of said individual looked like, so they must infer and use ‘guesswork’ to show parts of the phenotype when they do these ‘reconstructions’.

My reason for writing this is due to the ‘reconstruction’ of Nefertiti. I have seen altrighers proclaim ‘The Ancient Egyptians were white!’ whereas I saw blacks stating ‘Why are they whitewashing our history!’ Both of these claims are dumb, and they’re also wrong. Then you have articles—purely driven by ideology—that proclaim ‘Facial Reconstruction Reveals Queen Nefertiti Was White!‘

This article is garbage. It first makes the claim that King Tut’s DNA came back as being similar to 70 percent of Western European man. Though, there are a lot of problems with this claim. 1) the company IGENEA inferred his Y chromosome from a TV special; the data was not available for analysis. 2) Haplogroup does not equal race. This is very simple.

Now that the White race has decisively reclaimed the Ancient Egyptians

The white race has never ‘claimed’ the Ancient Egyptians; this is just like the Arthur Kemp fantasy that the Ancient Egyptians were Nordic and that any and all civilizations throughout history were started and maintained by whites, and that the causes of the falls of these civilizations were due to racial mixing etc etc. These fantasies have no basis in reality, and, now, we will have to deal with people pushing these facial ‘reconstructions’ that are largely just ‘art’, and don’t actually show us what the individual in question used to look like (more on this below).

Stephan (2003) goes through the four primary fallacies of facial reconstruction: fallacy 1) That we can predict soft tissue from the skull, that we can create recognizable faces. This is highly flawed. Soft tissue fossilization is rare—rare enough to be irrelevant, especially when discussing what ancient humans used to look like. So for these purposes, and perhaps this is the most important criticism of ‘reconstructions’, any and all soft tissue features you see on these ‘reconstructions’ are largely guesswork and artistic flair from the ‘reconstructor’. So facial ‘reconstructions’ are mostly art. So, pretty much, the ‘reconstructor’ has to make a ton of leaps and assumptions while creating his sculpture because he does not have the relevant information to make sure it is truly accurate, which is a large blow to facial ‘reconstructions’.

And, perhaps most importantly for people who push ‘reconstructions’ of ancient hominin: “The decomposition of the soft tissue parts of paleoanthropological beings makes it impossible for the detail of their actual soft tissue face morphology and variability to be known, as well as the variability of the relationship between the hard and the soft tissue.” and “Hence any facial “reconstructions” of earlier hominids are likely to be misleading [4].”

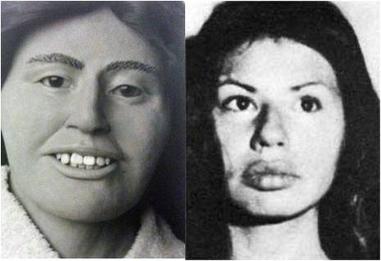

As an example for the inaccuracy of these ‘reconstructions’, see this image from Wikipedia:

The left is the ‘reconstruction’ while the right is how the woman looked. She had distinct lips which could not be recreated because, again, soft tissue is missing.

2) That faces are ‘reconstructed’ from skulls: This fallacy directly follows from fallacy 1: that ‘reconstructors’ can accurately predict what the former soft tissue looked like. Faces are not ‘reconstructed’ from skulls, it’s largely guesswork. Stephan states that individuals who see and hear about facial ‘reconstructions’ state things like “wow, you have to be pretty smart/knowledgeable to be able to do such a complex task”, which Stephan then states that facial ‘approximation’ may be a better term to use since it doesn’t imply that the face was ‘reconstructed’ from the skull.

3) That this discipline is ‘credible’ because it is ‘partly science’, but Stephan argues that calling it a science is ‘misleading’. But he writes (pg 196): “The fact that several of the commonly used subjective guidelines when scientifically evaluated have been found to be inaccurate, … strongly emphasizes the point that traditional facial approximation methods are not scientific, for if they were scientific and their error known previously surely these methods would have been abandoned or improved upon.”

And finally, 4) We know that ‘reconstructions’ work because they have been successful in forensic investigations. Though this is not a strong claim because other factors could influence the discovery, such as media coverage, chance, or ‘contextual information’. So these forensics cases cannot be pointed to when one attempts to argue for the utility of facial ‘reconstructions’. There also seems to be a lot of publication bias in this literature too, with many scientists not publishing data that, for instance, did not show the ‘face’ of the individual in question. It is largely guesswork. “The inconsistency in reports combined with confounding factors influencing casework success suggest that much caution should be employed when gauging facial approximation success based on reported practitioner success and the success of individual forensic cases” (Stephan, 2003: 196).

So, 1) the main point here is that soft tissue work is ‘just a guess’ and the prediction methods employed to guess the soft tissue have not been tested. 2) faces are not ‘reconstructed’ from skulls. 3) It’s hardly ‘science’, and more of a form of art due to the guesses and large assumptions poured into the ‘technique’. 4) ‘Reconstructions’ don’t ‘work’ because they help us ‘find’ people, as there is a lot more going on there than the freak-chance happenings of finding a person based on a ‘reconstruction’ which was probably due to chance. Hayes (2015) also writes: “Their actual ability to meaningfully represent either an individual or a museum collection is questionable, as facial reconstructions created for display and published within academic journals show an enduring preference for applying invalidated methods.”

Stephan and Henneberg (2001) write: “It is concluded that it is rare for facial approximations to be sufficiently accurate to allow identification of a target individual above chance. Since 403 incorrect identifications were made out of 592 identification scenarios, facial approximation should be considered to be a highly inaccurate and unreliable forensic technique. These results suggest that facial approximations are not very useful in excluding individuals to whom skeletal remains may not belong.”

Wilkinson (2010) largely agrees, but states that ‘artistic interpretation’ should be used only when “particularly for the morphology of the ears and mouth, and with the skin for an ageing adult” but that “The greatest accuracy is possible when information is available from preserved soft tissue, from a portrait, or from a pathological condition or healed injury.” But she also writes: “… the laboratory studies of the Manchester method suggest that facial reconstruction can reproduce a sufficient likeness to allow recognition by a close friend or family member.”

So to sum up: 1) There is insufficient data for tissue thickness. This just becomes guesswork and, of course, is up to artistic ‘interpretation’, and then becomes subjective to whichever individual artist does the ‘reconstruction’. Cartilage, skin and fat does not fossilize (only in very rare cases and I am not aware of any human cases). 2) There is a lack of methodological standardization. There is no single method to use to ‘guesstimate’ things like tissue thickness and other soft tissue that does not fossilize. 3) They are very subjective! For instance, if the artist has any type of idea in his head of what the individual ‘may have’ looked like, his presuppositions may go from his head to his ‘reconstruction’, thusly biasing a look he/she will believe is true. I think this is the case for Mitochondrial Eve; just because she lived in Africa doesn’t mean that she looks similar to any modern Africans alive today.

I would make the claim that these ‘reconstructions’ are not science, they’re just the artwork of people who have assumptions of what people used to look like (for instance, with Nefertiti) and they take their assumptions and make them part of their artwork, their ‘reconstruction’. So if you are going to view the special that will be on tomorrow night, keep in the back of your mind that the ‘reconstruction’ has tons of unvalidated assumptions thrown into it. So, no, Nefertiti wasn’t ‘white’ and Nefertiti wasn’t ‘white washed’; since these ‘methods’ are highly flawed and highly subjective, we should not state that “This is what Nefertiti used to look like”, because it probably is very, very far from the truth. Do not fall for facial ‘reconstructions’.

IQ, Interoception, and the Heartbeat Counting Task: What Does It Mean?

1400 words

We’re only one month into the new year and I may have come across the most ridiculous paper I think I’ll read all year. The paper is titled Knowledge of resting heart rate mediates the relationship between intelligence and the heartbeat counting task. They state that ‘intelligence’ is related to heartbeat counting task (HCT), and that HBC is employed as a measure of interoception—which is a ‘sense’ that helps one understand what is going on in their body, sensing the body’s internal state and physiological changes (Craig, 2003; Garfinkel et al, 2015).

Though, the use of HCT as a measure of interoception is controversial (Phillips et al, 1999; Brener and Ring, 2016) mostly because it is influenced by prior knowledge of one’s resting heart rate. The concept of interoception has been around since 1906, with the term first appearing in scientific journals in the 1942 (Ceunen, Vlaeyen, and Dirst, 2016). It’s also interesting to note that interoceptive accuracy is altered in schizophrenics (who had an average IQ of 101.83; Ardizzi et al, 2016).

Murphy et al (2018) undertook two studies: study one demonstrated an association with ‘intelligence’ and HCT performance whereas study 2 demonstrated that this relationship is mediated by one’s knowledge of resting heart rate. I will briefly describe the two studies then I will discuss the flaws (and how stupid the idea is that ‘intelligence’ partly is responsible for this relationship).

In both studies, they measured IQ using the Wechsler intelligence scales, specifically the matrix and vocabulary subtests. In study 1, they had 94 participants (60 female, 33 female, and one ‘non-binary’; gotta always be that guy eh?). In this study, there was a small but positive correlation between HCT and IQ (r = .261).

In study 2, they sought to again replicate the relationship between HCT and IQ, determine how specific the relationship is, and determine whether higher IQ results in more accurate knowledge of one’s heart rate which would then improve their scores. They had 134 participants for this task and to minimize false readings they were asked to forgo caffeine consumption about six hours prior to the test.

As a control task, participants were asked to complete a timing accuracy test (TAT) in which they were asked to count seconds instead of heartbeats. The correlation with HCT performance and IQ was, again, small but positive (r = -.211) with IQ also being negatively correlated with the inaccuracy of resting heart rate estimations (r = .363), while timing accuracy was not associated with the inaccuracy of heart rate estimates, IQ or HCT. In the end, knowledge of average resting heart rate completely mediated the relationship between IQ and HCT.

This study replicated another study by Mash et al (2017) who show that their “results suggest that cognitive ability moderates the effect of age on IA differently in autism and typical development.” This new paper then extends this analysis showing that it is fully mediated by prior knowledge of average resting heart rate, and this is key to know.

This is simple: if one has prior knowledge of their average resting heart rate and their fitness did not change from the time they were aware of their average resting heart rate then when they engage in the HCT they will then have a better chance of counting the number of beats in that time frame. This is very simple! There are also other, easier, ways to estimate your heart rate without doing all of that counting.

Heart rate (HR) is a strong predictor of cardiorespiratory fitness. So it would follow that those who have prior knowledge of their HRs would more fitness savvy (the authors don’t really say too much about the subjects if there is more data when the paper is published in a journal I will revisit this). So Murphy et al (2018) showed that 1) prior knowledge of resting heart rate (RHR) was correlated—however low—with IQ while IQ was negatively correlated with the inaccuracy of RHR estimates. So the second study replicated the first and showed that the relationship was specific (HCT correlated with IQ, not any other measure).

The main thing to keep in mind here is that those who had prior knowledge of their RHR scored better on the task; I’d bet that even those with low IQs would score higher on this test if they, too, had prior knowledge of their HRs. That’s, really, what this comes down to: if you have prior knowledge of your RHR and your physiological state stays largely similar (body fat, muscle mass, fitness, etc) then when asked to estimate your heart rate by, say, using the radial pulse method (placing two fingers along the right side of the arm in line just above the thumb), they, since they have prior knowledge, will more accurately guess their RHR, if they had low or high IQs, regardless.

I also question the use of the HCT as a method of interoception, in line with Brener and Ring (2016: 2) who write “participants with knowledge about heart rate may generate accurate counting scores without detecting any heartbeat sensations.” So let’s say that HCT is a good measure of interoception, then it still remains to be seen whether or not manipulating subjects’ HRs would change the accuracy of the analyses. Other studies have shown that testing HR after one exercises, people underestimate their HR (Brener and Ring, 2016: 2). This, too, is simple. To get your max HR after exercise, subtract your age from 220. So if you’re 20 years old, your max HR would be 200, and after exercise, if you know you’re body and how much energy you have expended, then you will be able to estimate better with this knowledge.

Though, you would need to have prior knowledge, of course, of these effects and knowledge of these simple formulas to know about this. So, in my opinion, this study only shows that people who have a higher ‘IQ’ (more access to cultural tools to score higher on IQ tests; Richardson, 2002) are also more likely to, of course, go to the doctor for checkups, more likely to exercise and, thusly, be more likely to have prior knowledge of their HR and score better than those with lower IQs and less access to these types of facilities where they would have access to prior knowledge and get health assesments to have prior knowledge like those with higher IQs (which are more likely to be middle class and have more access to these types of facilities).

I personally don’t think that HCT is a good measure of interoception due to the criticisms brought up above. If I have prior knowledge of my HR (average HR for a healthy person is between 50-75 BPM depending on age, sex, and activity (along with other physiological components) (Davidovic et al, 2013). So, for example,if my average HR is 74 (I just checked mine last week and I checked it in the morning, and averaged 3 morning tests one morning was 73, the other morning was 75 and the third was 74 for an average of 74 BPM), and I had this prior knowledge before undergoing this so-called HCT interoception task, I would be better equipped to score better than one who does not have the same prior knowledge of his own heart rate as I do.

In conclusion, in line with Brener and Ring (2016), I don’t think that HCT is a good measure for interoception, and even if it were, the fact that prior knowledge fully mediates this relationship means that, in my opinion, other methods of interoception need to be found and studied. The fact that if someone has prior knowledge of their HR can and would skew things—no matter their ‘IQ’—since they know that, say, their HR is in the average range (50-75 BPM). I find this study kind of ridiculous and it’s in the running for most ridiculous things I have read all year. Prior knowledge (both with RHR and PEHR; post-exercise heart rate) of these variables will have you score better and, since IQ is a measure of social class then with the small correlation between HCT and IQ found by Murphy et al (2018), some (but most is not) is mediated by IQ, which is just largely tests for skills found in a narrow social class, so it’s no wonder that they corrrlate—however low—and the reason why the relationship was found is obvious, especially if you have some prior knowledge of this field.

Calories are not Calories

1300 words

More bullocks from Dr. Thompson:

I say that if you are over-weight and wish to lose weight, then you should eat less. You should keep eating less until you achieve your desired weight, and then stick to that level of calorific intake.

Why only talk about calories and assume that they do the same things once ingested into the body? See Feinman and Fine (2004) to see how and why that is fallacious. This was actually studied. Contestants on the show The Biggest Loser were followed after they lost a considerable amount of weight. They followed the same old mantra: eat less, and move more. Because if you decrease what is coming in, and expend more energy then you will lose weight. Thermodynamics, energy in and out, right? That should put one into a negative energy balance and they should lose weight if they persist with the diet. And they did. However, what is going on with the metabolism of the people who lost all of this weight, and is this effect more noticeable for people who lost more weight in comparison to others?

Fothergill et al (2016) found that persistent metabolic slowdown occurred after weight loss, the average being a 600 kcal slowdown. This is what the conventional dieting advice gets you, a slowed metabolism with you having to eat fewer kcal than one who was never obese. This is what the ‘eat less, move more’ advice, the ‘CI/CO’ advice is horribly flawed and does not work!

He seems to understand that exercise does not work to induce weight loss, but it’s this supposed combo that’s supposed to be effective, a kind of one-two punch, and you only need to eat less and move more if you want to lose weight! This is horribly flawed. He then shows a few table from a paper he authored with another researcher back in 1974 (Bhanji and Thompson, 1974).

Say you take 30 people who weigh the same, have the same amount of body fat and are the same height, they eat the same exact macronutrient composition, with the same exact foods, eating at a surplus deficit with the same caloric content, and, at the end of say, 3 months, you will get a different array of weight gained/stalled/decrease in weight. Wow. Something like this would certainly disprove the CI/CO myth. Aamodt (2016: 138-139) describes a study by Bouchard and Tremblay (1997; warning: twin study), writing:

When identical twins, men in their early 20s, were fed a thousand extra calories per day for about three months, each pair showed similar weight gains. In contrast, the gains varied across twin pairs, ranging from nine to twenty-nine pound, even though the calorie imbalance esd the same for everyone. An individual’s genes also influence weight loss. When another group of identical twins burned a thousand more calories per day through exercise while maintaining a stable food intake in an inpatient facility, their losses ranged from two to eighteen pounds and were even more similar within twin pairs than weight gain.

Take a moment to think about that. Some people’s bodies resis weight loss so well that burning an extra thousand calpires a day for three months, without eating more, leads them to lose only two pounds. The “weight loss is just math” crows we met in the last chapter needs to look at what happens when their math is applied to living people. (We know what usually happens: they accuse the poor dieter of cheating, whether or not it’s true.) If cutting 3,500 calories equals one pound of weight loss, then everyone on the twuns’ exercist protocol should have lost twenty-four pounds, but not a single participant lost that much. The average weight loss was only eleven pounds, and the individual variation was huge. Such differences can result from genetic influences on resting metabolism, which varies 10 to 15 percent between people, or from differences in the gut. Because the thousand-calorie energy imbalance was the same in both the gain and loss experiments, this twin research also illustrates that it’s easier to gain weight than to lose it.

That’s weird. If a calorie were truly a calorie, then, at least in the was CI/COers word things, everyone should have had the same or similar weight loss, not with the average weight loss less than half what should have been expected from the kcal they consumed. That is a shot against the CI/CO theory. Yet more evidence against comes from the Vermont Prison Experiment (see Salans et al, 1971). In this experiment, they were given up to 10,000 kcal per day and they, like in the other study described previously, all gained differing amounts of weight. Wow, almost as if individuals are different and the simplistic caloric math of the CI/COers doesn’t size up against real-life situations.

The First Law of Thermodynamics always holds, it’s just irrelevant to human physiology. (Watch Gary Taubes take down this mythconception too; not a typo.) Think about an individual who decreases total caloric intake from 1500 kcal per day to 1200 kcal per day over a certain period of time. The body is then forced to drop its metabolism to match the caloric intake, so the metabolic system of the human body knows when to decrease when it senses it’s getting less intake, and for this reason the First Law is not violated here, it’s irrelevant. The same thing also occurred to the Biggest Loser contestants. Because the followed the CI/CO paradigm of ‘eat less and move more’.

Processed food is not bad in itself, but it is hard to monitor what is in it, and it is probably best avoided if you wish to lose weight, that is, it should not be a large part of your habitual intake.

If you’re trying to lose weight you should most definitely avoid processed foods and carbohydrates.

In general, all foods are good for you, in moderation. There are circumstances when you may have to eat what is available, even if it is not the best basis for a permanent sustained diet.

I only contest the ‘all foods are good for you’ part. Moderation, yes. But in our hedonistic world we live in today with a constant bombardment of advertisements there is no such thing as ‘moderation’. Finally, again, willpower is irrelevant to obesity.

I’d like to know the individual weight gains in Thompson’s study. I bet it’d follow both what occurred in the study described by Aamodt and the study by Sims et al. The point is, human physiological systems are more complicated than to attempt to break down weight loss to only the number of calories you eat, when not thinking of what and how you eat it. What is lost in all of this is WHEN is a good time to eat? People continuously speak about what to eat, where to eat, how to eat, who to eat with but no one ever seriously discusses WHEN to eat. What I mean by this is that people are constantly stuffing their faces all day, constantly spiking their insulin which then causes obesity.

The fatal blow for the CI/CO theory is that people do not gain or lose weight at the same rate (I’d add matched for height, overall weight, muscle mass and body fat, too) as seen above in the papers cited. Why people still think that the human body and its physiology is so simple is beyond me.

Hedonism along with an overconsumption of calories consumed (from processed carbohydrates) is why we’re so fat right now in the third world and the only way to reverse the trend is to tell the truth about human weight loss and how and why we get fat. CI/CO clearly does not work and is based on false premises, no matter how much people attempt to save it. It’s highly flawed and assumed that the human body is so ‘simple’ as to not ‘care’ about the quality of the macro nor where it came from.

I Am Not A Phrenologist

1500 words

People seem to be confused on the definition of the term ‘phrenology’. Many people think that just the measuring of skulls can be called ‘phrenology’. This is a very confused view to hold.

Phrenology is the study of the shape and size of the skull and then drawing conclusions from one’s character from bumps on the skull (Simpson, 2005) to overall different-sized areas of the brain compared to others then drawing on one’s character and psychology from these measures. Franz Gall—the father of phrenology—believed that by measuring one’s skull and the bumps etc on it, then he could make accurate predictions about their character and mental psychology. Gall had also proposed a theory of mind and brain (Eling, Finger, and Whitaker, 2017). The usefulness of phrenology aside, the creator Gall contributed a significant understanding to our study of the brain, being that he was a neuroanatomist and physiologist.

Gall’s views on the brain can be seen here (read this letter where he espouses his views here):

1.The brain is the organ of the mind.

2. The mind is composed of multiple, distinct, innate faculties.

3. Because they are distinct, each faculty must have a separate seat or “organ” in the brain.

4. The size of an organ, other things being equal, is a measure of its power.

5. The shape of the brain is determined by the development of the various organs.

6. As the skull takes its shape from the brain, the surface of the skull can be read as an accurate index of psychological aptitudes and tendencies.

Gall’s work, though, was imperative to our understanding of the brain and he was a pioneer in the inner workings of the brain. They ‘phrenologized’ by running the tips of their fingers or their hands along the top of one’s head (Gall liked using his palms). Here is an account of one individual reminiscing on this (around 1870):

The fellow proceeded to measure my head from the forehead to the back, and from one ear to the other, and then he pressed his hands upon the protuberances carefully and called them by name. He felt my pulse, looked carefully at my complexion and defined it, and then retired to make his calculations in order to reveal my destiny. I awaited his return with some anxiety, for I really attached some importance to what his statement would be; for I had been told that he had great success in that sort of work and that his conclusion would be valuable to me. Directly he returned with a piece of paper in his hand, and his statement was short. It was to the effect that my head was of the tenth magnitude with phyloprogenitiveness morbidly developed; that the essential faculties of mentality were singularly deficient; that my contour antagonized all the established rules of phrenology, and that upon the whole I was better adapted to the quietude of rural life rather than to the habit of letters. Then the boys clapped their hands and laughed lustily, but there was nothing of laughter in it for me. In fact, I took seriously what Rutherford had said and thought the fellow meant it all. He showed me a phrenological bust, with the faculties all located and labeled, representing a perfect human head, and mine did not look like that one. I had never dreamed that the size or shape of the head had anything to do with a boy’s endowments or his ability to accomplish results, to say nothing of his quality and texture of brain matter. I went to my shack rather dejected. I took a small hand- mirror and looked carefully at my head, ran my hands over it and realized that it did not resemble, in any sense, the bust that I had observed. The more I thought of the affair the worse I felt. If my head was defective there was no remedy, and what could I do? The next day I quietly went to the library and carefully looked at the heads of pictures of Webster, Clay, Calhoun, Napoleon, Alexander Stephens and various other great men. Their pictures were all there in histories.

This—what I would call skull/brain-size fetishizing—is still evident today, with people thinking that raw size matters (Rushton and Ankney, 2007; Rushton and Ankney, 2009) for cognitive ability, though I have compiled numerous data that shows that we can have smaller brains and have IQs in the normal range, implying that large brains are not needed for high IQs (Skoyles, 1999). It is also one of Deacon’s (1990) fallacies, the “bigger-is-smarter” fallacy. Just because you observe skull sizes, brain size differences, structural brain differences, etc, does not mean you’re a phrenologist. you’re making easy and verifiable claims, not like some of the outrageous claims made by phrenologists.

What did they get right? Well, phrenologists stated that the most-used part of the brain would become bigger, which, of course, was vindicated by modern research—specifically in London cab drivers (McGuire, Frackowiak, and Frith, 1997; Woolett and McGuire, 2011).

It seems that phrenologists got a few things right but their theories were largely wrong. Though those who bash the ‘science’ of phrenology should realize that phrenology was one of the first brain ‘sciences’ and so I believe phrenology should at least get some respect since it furthered our understanding of the brain and some phrenologists were kind of right.

People see the avatar I use which is three skulls, one Mongoloid, the other Negroid and the other Caucasoid and then automatically make that leap that I’m a phrenologist based just on that picture. Even, to these people, stating that races/individuals/ethnies have different skull and brain sizes caused them to state that what I was saying is phrenology. No, it isn’t. Words have definitions. Just because you observe size differences between brains of, say either individuals or ethnies, doesn’t mean that you’re making any value judgments on the character/mental aptitude of that individual based on the size of theur skull/brain. On the other hand, noting structural differences between brains like saying “the PFC is larger here but the OFC is larger in this brain than in that brain” yet no one is saying that and if that’s what you grasp from just the statement that individuals and groups have different sized skulls, brains, and parts of the brain then I don’t know what to tell you. Stating that one brain weighs more than another, say one is 1200 g and another is 1400 g is not phrenology. Stating that one brain is 1450 cc while another is 1000 cc is not phrenology. For it to be phrenology I have to outright state that differences in the size of certain areas of the brain or brains as a whole cause differences in character/mental faculties. I am not saying that.

A team of neuroscientists just recently (recently as in last month, January, 2018) showed, in the “most exhaustive way possible“, tested the claims from phrenological ‘research’ “that measuring the contour of the head provides a reliable method for inferring mental capacities” and concluded that there was “no evidence for this claim” (Jones, Alfaro-Almagro, and Jbabdi, 2018). That settles it. The ‘science’ is dead.

It’s so simple: you notice physical differences in brain size between two corpses. That one’s PFC was bigger than OFC and with the other, his OFC was bigger than his PFC. That’s it. I guess, using this logic, neuroanatomists would be considered phrenologists today since they note size differences between individual parts of brains. Just noting these differences doesn’t make any type of judgments on potential between brains of individuals with different size/overall size/bumps etc.

It is ridiculous to accuse someone of being a ‘phrenologist’ in 2018. And while the study of skull/brain sizes back in the 17th century did pave the way for modern neuroscience and while they did get a few things right, they were largely wrong. No, you cannot see one’s character from feeling the bumps on their skull. I understand the logic and, back then, it would have made a lot of sense. But to claim that one is a phrenologist or is pushing phrenology just because they notice physical differences that are empirically verifiable does not make them a phrenologist.

In sum, studying physical differences is interesting and tells us a lot about our past and maybe even our future. Stating that one is a phrenologist because they observe and accept physical differences in the size of the brain, skull, and neuroanatomic regions is like saying that physical anthropologists and forensic scientists are phrenologists because they measure people’s skulls to ascertain certain things that may be known in their medical history. Chastizing someone because they tell you that one has a different brain size than the other by calling them outdated names in an attempt to discredit them doesn’t make sense. It seems that even some people cannot accept physical differences that are measurable again and again because it may go against some long-held belief.

Responding to Jared Taylor on the Raven Progressive Matrices Test

2950 words

I was on Warski Live the other night and had an extremely short back-and-forth with Jared Taylor. I’m happy I got the chance to shortly discuss with him but I got kicked out about 20 minutes after being there. Taylor made all of the same old claims, and since everyone continued to speak I couldn’t really get a word in.

A Conversation with Jared Taylor

I first stated that Jared got me into race realism and that I respected him. He said that once you see the reality of race then history etc becomes clearer.

To cut through everything, I first stated that I don’t believe there is any utility to IQ tests, that a lot of people believe that people have surfeits of ‘good genes’ ‘bad genes’ that give ‘positive’ and ‘negative’ charges. IQ tests are useless and that people ‘fetishize them’. He then responded that IQ is one of, if not the, most studied trait in psychology to which JF then asked me if I contended that statement and I responded ‘no’ (behavioral geneticists need to work to ya know!). He then talked about how IQ ‘predicts’ success in life, e.g., success in college,

Then, a bit after I stated that, it seems that they painted me as a leftist because of my views on IQ. Well, I’m far right (not that my politics matters to my views on scientific matters) and they made it seem like I meant that Jared fetishized IQ, when I said ‘most people’.

Then Jared gives a quick rundown of the same old and tired talking points how IQ is related to crime, success, etc. I then asked him if there was a definition of intelligence and whether or not there was consensus in the psychological community on the matter.

I quoted this excerpt from Ken Richardson’s 2002 paper What IQ Tests Test where he writes:

Of the 25 attributes of intelligence mentioned, only 3 were mentioned by 25 per cent or more of respondents (half of the respondents mentioned `higher level components’; 25 per cent mentioned ‘executive processes’; and 29 per cent mentioned`that which is valued by culture’). Over a third of the attributes were mentioned by less than 10 per cent of respondents (only 8 per cent of the 1986 respondents mentioned `ability to learn’).

Jared then stated:

“Well, there certainly are differing ideas as to what are the differing components of intelligence. The word “intelligence” on the other hand exists in every known language. It describes something that human beings intuitively understand. I think if you were to try to describe sex appeal—what is it that makes a woman appealing sexually—not everyone would agree. But most men would agree that there is such a thing as sex appeal. And likewise in the case of intelligence, to me intelligence is an ability to look at the facts in a situation and draw the right conclusions. That to me is one of the key concepts of intelligence. It’s not necessarily “the capacity to learn”—people can memorize without being particularly intelligent. It’s not necessarily creativity. There could be creative people who are not necessarily high in IQ.

I would certainly agree that there is no universally accepted definition for intelligence, and yet, we all instinctively understand that some people are better able to see to the essence of a problem, to find correct solutions to problems. We all understand this and we all experience this in our daily lives. When we were in class in school, there were children who were smarter than other children. None of this is particularly difficult to understand at an intuitive level, and I believe that by somehow saying because it’s impossible to come up with a definition that everyone will accept, there is no such thing as intelligence, that’s like saying “Because there may be no agreement on the number of races, that there is no such thing as race.” This is an attempt to completely sidetrack a question—that I believe—comes from dishonest motives.”

(“… comes from dishonest motives”, appeal to motive. One can make the claim about anyone, for any reason. No matter the reason, it’s fallacious. On ‘ability to learn’ see below.)

Now here is the fun part: I asked him “How do IQ tests test intelligence?” He then began talking about the Raven (as expected):

“There are now culture-free tests, the best-known of which is Raven’s Progressive Matrices, and this involves recognizing patterns and trying to figure out what is the next step in a pattern. This is a test that doesn’t require any language at all. You can show an initial simple example, the first square you have one dot, the next square you have two dots, what would be in the third square? You’d have a choice between 3 dots, 5 dots, 20 dots, well the next step is going to be 3 dots. You can explain what the initial patterns are to someone who doesn’t even speak English, and then ask them to go ahead and go and complete the suceeding problems that are more difficult. No language, involved at all, and this is something that correlates very, very tightly with more traditonal, verbally based, IQ tests. Again, this is an attempt to measure capacity that we all inherently recognize as existing, even though we may not be able to define it to everyone’s mutual satisfaction, but one that is definitely there.

Ultimately, we will be able to measure intelligence through direct assessment of the brain, that it will be possible to do through genetic analysis. We are beginning to discover the gene patterns associated with high intelligence. Already there have been patent applications for IQ tests based on genetic analysis. We really aren’t at the point where spitting in a cup and analyzing the DNA you can tell that this guy has a 140 IQ, this guy’s 105 IQ. But we will eventually get there. At the same time there are aspects of the brain that can be analyzed, repeatedly, with which the signals are transmitted from one part of the brain to the other, the density of grey matter, the efficiency with which white matter communicates between the different grey matter areas of the brain.

I’m quite confident that there will come a time where you can just strap on a set of electrodes and have someone think about something—or even not think about anything at all—and we will be able to assess the power of the brain directly through physical assessment. People are welcome to imagine that this is impossible, or be skeptical about that, but I think we’re defintely moving in that direction. And when the day comes—when we really have discovered a large number of the genetic patterns that are associated with high intelligence, and there will be many of them because the brain is the most complicated organ in the human body, and a very substantial part of the human genome goes into constructing the brain. When we have gotten to the bottom of this mystery, I would bet the next dozen mortgage payments that those patterns—alleles as they’re called, genetic patterns—that are associated with high intelligence will not be found to be equally distributed between people of all races.”

Then immediately after that, the conversation changed. I will respond in points:

1) First off, as I’m sure most long-time readers know, I’m not a leftist and the fact that (in my opinion) I was implied to be a leftist since I contest the utility of IQ is kind of insulting. I’m not a leftist, nor have I ever been a leftist.

2) On his points on definitions of ‘intelligence’: The point is to come to a complete scientific consensus on how to define the word, the right way to study it and then think of the implications of the trait in question after you empirically verify its reality. That’s one reason to bring up how there is no consensus in the psychological community—ask 50 psychologists what intelligence is, get numerous different answers.

3) IQ and success/college: Funny that gets brought up. IQ tests are constructed to ‘predict’ success since they’re similar already to achievement tests in school (read arguments here, here, and here). Even then, you would expect college grades to be highly correlated with job performance 6 years after graduation from college right? Wrong. Armstrong (2011: 4) writes: “Grades at universities have a low relationship to long-term job performance (r = .05 for 6 or more years after graduation) despite the fact that cognitive skills are highly related to job performance (Roth, et al. 1996). In addition, they found that this relationship between grades and job performance has been lower for the more recent studies.” Though the claim that “cognitive skills are highly related to job performance” lie on shaky ground (Richardson and Norgate, 2015).

4) My criticisms on IQ do not mean that I deny that ‘intelligence exists’ (which is a common strawman), my criticisms are on construction and validity, not the whole “intelligence doesn’t exist” canard. I, of course, don’t discard the hypothesis that individuals and populations can differ in ‘intelligence/intelligence ‘genes’, the critiques provided are against the “IQ-tests-predict-X-in-life” claims and ‘IQ-tests-test-‘intelligence” claims. IQ tests test cultural distance from the middle class. Most IQ tests have general knowledge questions on them which then contribute a considerable amount to the final score. Therefore, since IQ tests test learned knowledge present in some cultures and not in others (which is even true for ‘culture-fair’ tests, see point 5), then learning is intimately linked with Jared’s definition of ‘intelligence’. So I would necessariliy state that they do test learned knowledge and test learned knowledge that’s present in some classes compared to others. Thusly, IQ tests test learned knowledge more present in some certain classes than others, therefore, making IQ tests proxies for social class, not ‘intelligence’ (Richardson, 2002; 2017b).

5) Now for my favorite part: the Raven. The test that everyone (or most people) believe is culture-free, culture-fair since there is nothing verbal thusly bypassing any implicit suggestion that there is cultural bias in the test due to differences in general knowledge. However, this assumption is extremely simplistic and hugely flawed.

For one, the Raven is perhaps one of the most tests, even more so than verbal tests, reflecting knowledge structures present in some cultures more than others (Richardson, 2002). One may look at the items on the Raven and then proclaim ‘Wow, anyone who gets these right must be ‘intelligent”, but the most ‘complicated’ Raven’s items are not more complicated than everyday life (Carpenter, Just, and Shell, 1990; Richardson, 2002; Richardson and Norgate, 2014). Furthermore, there is no cognitive theory in which items are selected for analysis and subsequent entry onto a particular Raven’s test. Concerning John Raven’s personal notes, Carpenter, Just, and Shell (1990: 408) show that John Raven—the creator of the Raven’s Progressive Matrices test—used his “intuition and clinical experience” to rank order items “without regard to any underlying processing theory.”

Now to address the claim that the Raven is ‘culture-free’: take one genetically similar population, one group of them are foraging hunter-gatherers while the other population lives in villages with schools. The foraging people are tested at age 11. They score 31 percent, while the ones living in more modern areas with amenities get 72 percent right (‘average’ individuals get 78 percent right while ‘intellectually defective’ individuals get 47 percent right; Heine, 2017: 188). The people I am talking about are the Tsimane, a foraging, hunter-gatherer population in Bolivia. Davis (2014) studied the Tsimane people and administered the Raven test to two groups of Tsimane, as described above. Now, if the test truly were ‘culture-free’ as is claimed, then they should score similarly, right?

Wrong. She found that reading was the best predictor of performance on the Raven. Children who attend school (presumably) learn how to read (with obviously a better chance to learn how to read if you don’t live in a hunter-gatherer environment). So the Tsimane who lived a more modern lifestyle scored more than twice as high on the Raven when compared to those who lived a hunter-gatherer lifestyle. So we have two genetically similar populations, one is exposed to more schooling while the other is not and schooling is the most related to performance on the Raven. Therefore, this study is definitive proof that the Raven is not culture-fair since “by its very nature, IQ testing is culture bound” (Cole, 1999: 646, quoted by Richardson, 2002: 293).

6) I doubt that we will be able to genotype people and get their ‘IQ’ results. Heine (2017) states that you would need all of the SNPs on a gene chip, numbering more than 500,000, to predict half of the variation between individuals in IQ (Davies et al, 2011; Chabris et al, 2012). Furthermore, since most genes may be height genes (Goldstein, 2009). This leads Heine (2017: 175) to conclude that “… it seems highly doubtful, contra Robert Plomin, that we’ll ever be able to estimate someone’s intelligence with much precision merely by looking at his or her genome.”

I’ve also critiqued GWAS/IQ studies by making an analogous argument on testosterone, the GWAS studies for testosterone, and how testosterone is produced in the body (its indirectly controlled by DNA, while what powers the cell is ATP, adenosine triphosphate (Kakh and Burnstock, 2009).

7) Regarding claims on grey and white matter: he’s citing Haier et al’s work, and their work on neural efficiency, white and grey matter correlates regarding IQ, to how different networks of the brain “talk” to each other, as in the P-FIT hypothesis of Jung and Haier (2007; numerous critiques/praises). Though I won’t go in depth on this point here, I will only say that correlations from images, correlations from correlations etc aren’t good enough (the neural network they discuss also may be related to other, noncognitive, factors). Lastly, MRI readings are known to be confounded by noise, visual artifacts and inadequate sampling, even getting emotional in the machine may cause noise in the readings (Okon-Singer et al, 2015) and since movements like speech and even eye movements affect readings, when describing normal variation, one must use caution (Richardson, 2017a).

8) There are no genes for intelligence (I’d also say “what is a gene?“) in the fluid genome (Ho, 2013), so due to this, I think that ‘identifying’ ‘genes for’ IQ will be a bit hard… Also touching on this point, Jared is correct that many genes—most, as a matter of fact—are expressed in the brain. Eighty-four percent, to be exact (Negi and Guda, 2017), so I think there will be a bit of a problem there… Further complicating these types of matters is the matter of social class. Genetic population structures have also emerged due to social class formation/migration. This would, predictably, cause genetic differences between classes, but these genetic differences are irrelevant to education and cognitive ability (Richardson, 2017b). This, then, would account for the extremely small GWAS correlations observed.

9) For the last point, I want to touch briefly on the concept of heritability (because I have a larger theme planned for the concept). Heritability ‘estimates’ have both group and individual flaws; environmental flaws; genetic flaws (Moore and Shenk, 2017), which arise due to the use of the highly flawed CTM (classical twin method) (Joseph, 2002; Richardson and Norgate, 2005; Charney, 2013; Fosse, Joseph, and Richardson, 2015). The flawed CTM inflates heritabilities since environments are not equalized, as they are in animal breeding research for instance, which is why those estimates (which as you can see are lower than the sky-high heritabilities that we get for IQ and other traits) are substantially lower than the heritabilities we observe for traits observed from controlled breeding experiments; which “surpasses almost anything found in the animal kingdom” (Schonemann, 1997: 104).

Lastly, there are numerous hereditarian scientific fallacies which include: 1) trait heritability does not predict what would occur when environments/genes change; 2) they’re inaccurate since they don’t account for gene-environment covariation or interaction while also ignoring nonadditive effects on behavior and cognitive ability; 3) molecular genetics does not show evidence that we can partition environment from genetic factors; 4) it wouldn’t tell us which traits are ‘genetic’ or not; and 5) proposed evolutionary models of human divergence are not supported by these studies (since heritability in the present doesn’t speak to what traits were like thousands of years ago) (Bailey, 1997). We, then, have a problem. Heritability estimates are useful for botanists and farmers because they can control the environment (Schonemann, 1997; Moore and Shenk, 2017). Regarding twin studies, the environment cannot be fully controlled and so they should be taken with a grain of salt. It is for these reasons that some researchers call to end the use of the term ‘heritability’ in science (Guo, 2000). For all of these reasons (and more), heritability estimates are useless for humans (Bailey, 1997; Moore and Shenk, 2017).

Still, other authors state that the use of heritability estimates “attempts to impose a simplistic and reified dichotomy (nature/nurture) on non-dichotomous processes.” (Rose, 2006) while Lewontin (2006) argues that heritability is a “useless quantity” and that to better understand biology, evolution, and development that we should analyze causes, not variances. (I too believe that heritability estimates are useless—especially due to the huge problems with twin studies and the fact that the correct protocols cannot be carried out due to ethical concerns.) Either way, heritability tells us nothing about which genes cause the trait in question, nor which pathways cause trait variation (Richardson, 2012).

In sum, I was glad to appear and discuss (however shortly) with Jared. I listened to it a few times and I realize (and have known before) that I’m a pretty bad public speaker. Either way, I’m glad to get a bit of points and some smaller parts of the overarching arguments out there and I hope I have a chance in the future to return on that show (preferably to debate JF on IQ). I will, of course, be better prepared for that. (When I saw that Jared would appear I decided to go on to discuss.) Jared is clearly wrong that the Raven is ‘culture-free’ and most of his retorts were pretty basic.

(Note: I will expand on all 9 of these points in separate articles.)