Examining Misguided Notions of Evolutionary “Progress”

2650 words

Introduction

For years, PumpkinPerson (PP) has been pushing an argument which states that “if you’re the first branch, and you don’t do anymore branching, then you’re less evolved than higher branches.” This is the concept of “more evolved” or the concept of evolutionary progress. Over the years I have written a few articles on the confused nature of this thinking. PP seems to like the argument since Rushton deployed a version of it for his r/K selection (Differential K) theory, which stated that “Mongoloids” are more “K evolved” than “Caucasians” who are more “K evolved” than “Negroids”, to use Rushton’s (1992) language. Rushton posited that this ordering occurred due to the cold winters that the ancestors of “Mongoloids” and “Caucasoids” underwent, and he theorized that this led to evolutionary progress, which would mean that certain populations are more advanced than others (Rushton, 1992; see here for response). It is in this context that PP’s statement above needs to be carefully considered and analyzed to determine its implications and relevance to Rushton’s argument. It commits the affirming the consequent fallacy, and assuming the statement is true leads to many logical inconsistenties like there being a “most evolved” species,

Why this evolutionary progress argument is fallacious

if you’re the first branch, and you don’t do anymore branching, then you’re less evolved than higher branches.

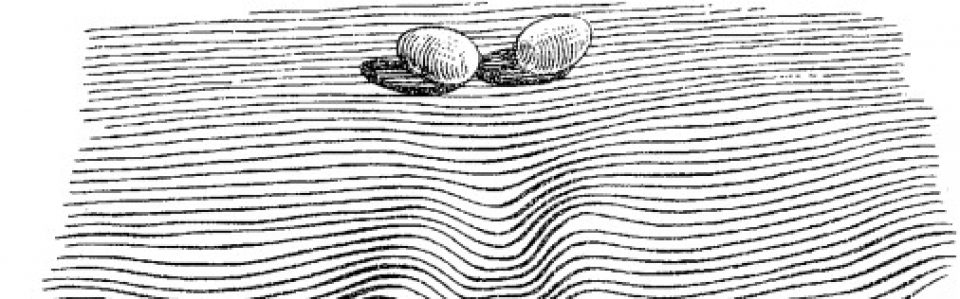

This is one of the most confused statements I have ever read on the subject of phylogenies. This misconception, though, is so widespread that there have been quite a few papers that talk about this and talk about how to steer students away from this kind of thinking about evolutionary trees (Crisp and Cook, 2004; Baum, Smith, and Donovan, 2005; Gregory, 2008; Omland, Cook, and Crisp, 2008). This argument is invalid since the concept of “evolved” in evolutionary trees doesn’t refer to a hierarchical scale, where higher branches are “more evolved” than lower branches (which are “less evolved”). What evolutionary trees do is show historical relationships between different species, which shows common ancestry and divergence over time. So each branch represents a lineage and all living organisms have been evolving foe the same amount of time since the last common ancestor (LCA). Thus, the position of a branch on the tree doesn’t determine a species’ level of evolution.

The argument is invalid since it incorrectly assumes that the position of the branch on a phylogeny determines the evolution or the “evolutionary advancement” of a species. Here’s how I formulate this argument:

(P1) If you’re the first branch on the evolutionary tree and you don’t do any more branching, then you’re less evolved than higher branches.

(P2) (Assumption) Evolutionary advancement is solely determined by the position on the tree and the number of branches.

(C) So species represented by higher branches on the evolutionary tree are more evolved than species represented by lower branches.

There is a contradiction in P2, since as I explained above, each branch represents a new lineage and every species on the tree is equally evolved. PP’s assumption seems to be that newer branches have different traits than the species that preceded it, implying that there is an advancement occurring. Nevertheless, I can use a reductio to refute the argument.

Let’s consider a hypothetical scenario in which this statement is true: “If you’re the first branch and you don’t do any more branching, then you’re less evolved than higher branches.” This suggests that the position of a species on a phylogeny determines its level of evolution. So according to this concept, if a species occupies a higher branch, it should be “more evolved” than a species on a lower branch. So following this line of reasoning, a species that has undergone extensive branching and diversification should be classified as “more evolved” compared to a species that has fewer branching points.

Now imagine that in this hypothetical scenario, we have species A and species B in a phylogeny. Suppose that species A is the first branch and that it hasn’t undergone any branching. Conversely, species B, which is represented on a higher branch, has experienced extensive branching and diversification, which adheres to the criteria for a species to be considered “more evolved.” But there are logical implications for the concept concerning the positions of species A and species B on the phylogeny.

So according to the concept of linear progression which is implied in the original statement, if species B is “more evolved” than species A due to its higher branch position, it logically follows that species B should continue to further evolve and diversify. This progression should lead to new branching points, as each subsequent stage would be considered “more evolved” than the last. Thus, applying the line of reasoning in the original statement, it suggests that there should always be a species represented on an even higher branch than species B, and this should continue ad infinitim, with no endpoint.

The logical consequence of the statement is that an infinite progression of increasingly evolved species, each species being represented by a higher branch than the one before, without any final of ultimate endpoint for a “most evolved” species. This result leads to an absurdity, since it contradicts our understanding of evolution as an ongoing and continuous process. The idea of a linear and hierarchical progression of a species in an evolutionary tree culminating in a “most evolved” species isn’t supported by our scientific understanding and it leads to an absurd outcome.

Thus, the logical implications of the statement “If you’re the first branch and you don’t do any more branching, then you’re less evolved than higher branches” leads to an absurd and contradictory result and so it must be false. The concept of the position of a species on an evolutionary tree isn’t supported by scientific evidence and understanding. Phylogenies represent historical relationships and divergence events over time.

(1) Assume the original claim is true: If you’re the first branch and you don’t do any more branching, then you’re less evolved than higher branches.

(2) Suppose species A is the first branch and undergoes no further branching.

(3) Now take species B which is in a higher branch which has undergone extensive diversification and branching, making it “more evolved”, according to the statement in (1).

(4) But based on the concept of linear progression implied in (1), species B should continue to evolved and diversity even further, leading to new branches and increased evolution.

(5) Following the logic in (1), there should always be a species represented on an even higher branch than species B, which is even more evolved.

(6) This process should continue ad infinitim with species continually branching and becoming “more evolved” without an endpoint.

(7) This leads to an absurd result, since it suggests that there is no species that could be considered “more evolved” or reach a final stage of evolution, contradicting our understanding of evolution as a continuous, ongoing process, with no ultimate endpoint.

(8) So since the assumption in (1) leads to an absurd result, then it must be false.

So the original statement is false, and a species’ position on a phylogeny doesn’t determine the level of evolution and the superiority of a species. The concept of a linear and hierarchical progression of advancement in a phylogeny is not supported by scientific evidence and assuming the statement in (1) is true leads to a logically absurd outcome. Each species evolves in its unique ecological context, without reaching a final state of evolution or hierarchical scale of superiority. This reductio ad absurdum argument therefore reveals the fallacy in the original statement.

Also, think about the claim that there are species that are “more evolved” than other species. This implies that there are “less evolved” species. Thus, a logical consequence of the claim is that there could be a “most evolved” species.

So if a species is “most evolved”, it would mean that that species has surpassed all others in evolutionary advancement and there are no other species more advanced than it. Following this line of reasoning, there should be no further branching or diversification of this species since it has already achieved the highest level of evolution. But evolution is an ongoing process. Organisms continously adapt to and change their surroundings (the organism-environment system), and change in response to this. But if the “most evolved” species is static, this contradicts what we know about evolution, mainly that it is continuous, ongoing change—it is dynamic. Further, as the environment changes, the “most evolved” species could become less suited to the environment’s conditions over time, leading to a decline in its numbers or even it’s extinction. This would then imply that there would have been other species that are “more evolved.” (It merely shows the response of the organism to its environment and how it develops differently.) Finally, the idea of a “most evolved” species implies an endpoint of evolution, which contradicts our knowledge of evolution and the diversification of life one earth. Therefore, the assumption that there is a “most evolved” species leads to a logical contradiction and an absurdity based on what we know about evolution and life on earth.

The statement possesses scala naturae thinking, which is also known as the great chain of being. This is something Rushton (2004) sought to bring back to evolutionary biology. However, the assumptions that need to hold for this to be true—that is, the assumptions that need to hold for this kind of tree reading to even be within the realm of possibility is false. This is wonderfully noted by Gregory (2008) who states that “The order of terminal noses is meaningless.” Crisp and Cook (2004) also state how such tree-reading is intuitive and this intuition of course is false:

Intuitive interpretation of ancestry from trees is likely to lead to errors, especially the common fallacy that a species-poor lineage is more ‘ancestral’ or ‘diverges earlier’ than does its species-rich sister group. Errors occur when trees are read in a one-sided way, which is more commonly done when trees branch asymmetrically.

There are several logical implications of that statement. I’ve already covered the claim that there is a kind of progression and advancement in evolution—a linear and hierarchical ranking—and the fixed endpoint (“most evolved”). Further, in my view, this leads to value judgments, that some species are “better” or “superior” to others. It also seems to ignore that the branching signifies not which species has undergone more evolution, but the evolutionary relationships between species. Finally, evolution occurs independently in each lineage and is based on their specific histories and interactions between developmental resources, it’s not valid to compare species as “more evolved” than others based on the relationships between species on evolutionary trees, so it’s based on an arbitrary comparison between species.

Finally, I can refute this using Gould’s full house argument.

P1: If evolution is a ladder of progress, with “more evolved” species on higher rungs, then the fossil record should demonstrate a steady increase in complexity over time.

P2: The fossils record does not shit a steady increase in complexity over time.

C: Therefore, evolution is not a ladder of progress and species cannot be ranked as “more evolved” based on complexity.

P1: If the concept of “more evolved” is valid, then there would be a linear and hierarchical progression in the advancement of evolution, wjtcertsin species considered superior to others based on their perceived level of evolutionary change.

P2: If there a linear and hierarchical progression of advancement in evolution, then the fossil record should demonstrate a steady increase in complexity over time, with species progressively becoming more complex and “better” in a hierarchical sense.

P3: The fossils record does not show a steady increase in complexity over time; it instead shows a diverse and branching pattern of evolution.

C1: So the concept of “more evolved” isn’t valid, since there is an absence of a steady increase in complexity in the fossil record and this refutes the notion of a linear and hierarchical progression of advancement in evolution.

P4: If the concept of “more evolved” is not valid, then there is no objective hierarchy of superiority among species based in their positions on an evolutionary tree.

C2: Thus, there is no objective hierarchy of superiority among species based on their positions on an evolutionary tree.

There is one final fallacy contained in that statement: it affirms the consequent. This logical fallacy takes the form of: If P then Q, P is true so Q is true.” Even if the concept of “more evolved” were valid, just because a species doesn’t do any more branching doesn’t mean it’s less evolved. So this reasoning is as follows: If you’re the first branch and you don’t do anymore branching, then you’re less evolved than higher branches (If P and Q, then R). It affirms the consequent like this: You didn’t do anymore branching (Q), so this branch has to be less evolved than the higher branches (R). It incorrectly infers the consequent Q (not doing anymore branching) as a sufficient condition for the antecedent P (being the first branch), which leads to the flawed conclusion (R) that the species is less evolved than higher branches. Just because a species doesn’t do anymore branching doesn’t mean it’s less evolved than another species. There could be numerous reasons why branching didn’t occur and it doesn’t directly determine evolutionary status. The argument infers being less evolved from doing less branching, which affirms the consequent. If a species doesn’t do anymore branching then that branch is less evolved than a higher branch. So since the argument affirms the consequent, it is therefore invalid.

Conclusion

Reading phylogenies in such a manner—in a way that would make one infer the conclusion that evolution is progressive and that there are “more evolved” species—although intuitive is false. Misconceptions like this along with many others while reading evolutionary trees are so persistent that much thought has been put into educating the public on right and wrong ways to read evolutionary trees.

As I showed in my argument ad absurdums where I accepted the claim as true, it leads to logical inconsistenties and goes against everything we know about evolution. Evolution is not progressive, it’s merely local change. That a species changes over time from another species doesn’t imply anything about “how evolved” (“more or less”) it is in comparison to the other. Excising this thinking is tough, but it is doable by understanding how evolutionary trees are constructed and how to read them correctly. It further affirms the consequent, leading to a false conclusion.

All living species have spent the same amount of time evolving. Branching merely signifies a divergence, not a linear scale of advancement. Of course one would think that if evolution is happening and one species evolves into another and that this relationship is shown on a tree that this would indicate that the newer species is “better” in some way in comparison to the species it derived from. But it merely suggests that the species faced different challenges which influenced its evolution; each species adapted and survived in its own unique evolutionary ecology, leading to diversification and the formation of newer branches on the tree. Evolution does not follow a linear path of progress, and there is no inherent hierarchy of superiority among species based on their position on the evolutionary tree. While the tree visually represents relationships between species, it doesn’t imply judgments like “better” or “worse”, “more evolved” or “less evolved.” It merely highlights the complexity and diversity of all life on earth.

Evolution is quite obviously not progressive, and even if it were, we wouldn’t see evolutionary progression from reading evolutionary trees, since such evolutionary relationships between species can be ladderized or not, with many kinds of different branches that may not be intuitive to those who read evolutionary trees as showing “more evolved” species, they nevertheless show a valid evolutionary relationship.

Dissecting Genetic Reductionism in Lead Litigation: Big Lead’s Genetic Smokescreen

2300 words

Lead industries have a history of downplaying or shifting the blame to avoid accountability for the deleterious effects of lead on public health, especially in vulnerable populations like children. As of the year 2002, about 35 percent of all low-income housing had lead hazards (Jacobs et al, 2002). Though another more recent analysis stated that 38 millions homes in the US (about 40 percent of homes) contained at least trace levels of lead, which was added to the paint before the use of lead in residential paint was banned in 1978. The American Healthy Homes Survey showed that 37.5 millions homes had at least some levels of lead in the paint (Dewalt et al, 2015). Since lead paint is more likely to be found in low-income households, public housing (Rabito, Shorter, and White, 2003) and minorities are more likely to be low-income, then it follows that minorities are more likely to be exposed to lead paint in the home—this is what we find (Carson, 2018; Eisenberg et al, 2020; Baek et al, 2021; McFarland, Hauer, and Reuben, 2022). The fact of the matter is, there is a whole host of negative effects of lead on the developing child, and there is no “safe level” of lead exposure, a point I made back in 2018:

There is a large body of studies which show that there is no safe level of lead exposure (Needleman and Landrigan, 2004; Canfield, Jusko, and Kordas, 2005; Barret, 2008; Rossi, 2008; Abelsohn and Sanborn, 2010; Betts, 2012; Flora, Gupta, and Tiwari, 2012; Gidlow, 2015; Lanphear, 2015; Wani, Ara, and Usmani, 2015; Council on Environmental Health, 2016; Hanna-Attisha et al, 2016; Vorvolakos, Aresniou, and Samakouri, 2016; Lanphear, 2017). So the data is clear that there is absolutely no safe level of lead exposure, and even small effects can lead to deleterious outcomes.

This story reminds me of a similar story, which I will discuss at the end, one of Waneta Hoyt and SIDS. I will compare these two and argue that the underlying issues are the same, privileging genetic factors over other, more obvious environmental factors. After discussing how Big Lead attempted to downplay and shift the blame of what lead was doing to these children, I will liken it to the Waneta Hoyt case.

Big Lead’s downplaying of the deleterious effects of lead on developing children

We have known that lead pipes were a cause of lead poisoning since the late 1800s, and lead companies attempted to reverse this by publishing studies and reports that showed that lead was better than other kinds of materials that could be used for the same purpose (Rabin, 2008). The Lead Industries Association (LIA) even blocked bans against lead paint and pipes, even after being aware of the issues they caused. So why, even after knowing that lead pipes were a primary cause of lead poisoning, were they used to distribute water and paint homes? The answer is simple: Corporate lobbying and outright lying and downplaying of the deleterious effects of lead. Due to our knowledge of the effects of lead in pipes and consequently drinking water, they began to be phased out around the 1920s. One way they attempted to downplay the obviously causal association between lead pipes and deleterious effects was to question it and say it still needed to be tested, one Lead Industries of America (LIA) member noted (quoted in Rabin, 2008):

Of late the lead industries have been receiving much undesirable publicity regarding lead poisoning. I feel the association would be wise to devote time and money on an impartial investigation which would show once and for all whether or not lead is detrimental to health under certain conditions of use.

Lead industries even promoted the use of lead in paint even after it was known that it leads to negative effects if paint chips are ingested by children (Rabin, 1989; Markowitz and Rosner, 2000). So we now have two examples on how Big Lead arranged to downplay the obviously causal, deleterious effects of lead on the developing child. But there are some more sinister events hiding in these shadows, and that is actually putting low-income (mostly black) families into homes with lead paint in order to study their outcomes and blood, as Harriet Washington (2019: 56-57) wrote in her A Terrible Thing to Waste: Environmental Racism and its Assault on the American Mind:

But Baltimore slumlords find removing this lead too expensive and some simply abandon the toxic houses. Cost concerns drove the agenda of the KKI researchers, who did not help parents completely remove children from sources of lead exposure. Instead, they allowed unwitting children to be exposed to lead in tainted homes, thus using the bodies of the children to evaluate cheaper, partial lead-abatement techniques of unknown efficacy in the old houses with peeling paint. Although they knew that only full abatement would protect these children, scientists decided to explore cheaper ways of reducing the lead threat.

So the KKI encouraged landlords of about 125 lead-tainted housing units to rent to families with young children. It offered to facilitate the landlords’ financing for partial lead abatement—only if the landlords rented to families with young children. Available records show that the exposed children were all black.

KKI researchers monitored changes in the children’s health and blood-lead levels, noting the brain and developmental damage that resulted from different kinds of lead-abatement programs.

These changes in the children’ bodies told the researchers how efficiently the different, economically stratified abatement levels worked. The results were compared to houses that either had been completely lead-abated or that were new and presumed not to harbor lead.

Scientists offered parents of children in these lead-laden homes incentives such as fifteen-dollar payments to cooperate with the study, but did not warn parents that the research potentially placed their children at risk of lead exposure.

Instead, literature given to the parents promised that researchers would inform them of any hazards. But they did not. And parents were not warned that their children were in danger, even after testing showed rising lead content in their blood.

Quite obviously, the KKI (Kennedy Krieger Institute) and the landlords were a part of an unethical study with no informed consent. The study was undertaken to test the effectiveness of three measures which cost a differing amount of money (Rosner and Markowitz, 2012) but this study was clearly unethical (Sprigg, 2004).

The Maryland Court of Appeals (2001) called this “innately inappropriate.” This is also obviously a case in which lower-income (majority black) people were already exposed to the higher levels of lead, and they then put them into homes that were “partially abated” of lead and comparing them to homes that had no lead. They knew that only full lead abatement would have been protective but still chose to place them into homes with “partial abatement” but they knowingly chose the cheaper option at the cost of the health of children. They also didn’t expose the parents to the full context of what they were trying to accomplish, thereby putting unwitting people into their clearly unethical study.

In 2002, Tamiko Jones and others brought on a suit against the owner of the apartment building and National Lead Industries, claiming that lead paint in the home was the cause of their children’s maladies and negative outcomes (Tamiko Jones, et al., v. NL Industries, et al. (Civil Action No. 4:03CV229)). Unfortunately, after a 3 week trial, the defendants lost the case and subsequent appeals were denied. But some of the things that the witnesses the defense brought up to the court caught my attention, since it’s similar to the story of Waneta Hoyt.

NL Industries attempted what I am calling “the gene defense.” The gene defense they used was that the children’s problems weren’t caused by lead in the paint, but it was caused by genetic and familial factors which then led to environmental deprivation. One of the mothers in the case, Sherry Wragg, was quoted as saying “My children didn’t have problems until we moved in here.” So the children that moved into this apartment building with their parents began to have behavioral and cognitive problems after they moved in, and they stated that it was due to the paint that had lead in it.

So the plaintiffs were arguing that the behavioral and cognitive deficits the children had were due to the leaded paint. Although the defense did acknowledge that the plaintiffs suffered from “economic deprivation”, which was a contributor to their maladies, they tried to argue that a familial history of retardation and environmental and economic deprivation explained the cognitive and behavioral deficits. But the defense argued that these deficits were explained by familial factors and genes which then explained the environmental deprivation. (Though the Court did recognize that the defense witnessed did not have expertise in toxicology.)

Plaintiffs first seek to strike two experts who provide arguably duplicative expert testimony that plaintiffs’ neurological deficits were most likely caused by genetic, familial and environmental factors, rather than lead exposure. For example, Dr. Barbara Quinten, director of the medical genetics department at Howard University, testified to her view that various plaintiffs had familial histories of low intelligence and/or mental retardation which explained their symptoms. Dr. Colleen Parker, professor of pediatrics and neurology at the University of Mississippi Medical Center, similarly testified that such factors as “familial history of retardation, poor environmental stimulation, and economic deprivation,” rather than elevated blood lead levels, explained the plaintiffs’ deficits.

So it seems that the defense was using the “genes argument” for behavior and cognition to try to make it ambiguous as to what was the cause of the issues the children were having. This is, yet again, another way in which IQ tests have been weaponized. “IQ has a hereditary, genetic component, and this family has familial history of these issues, so it can’t be shown that our lead paint was the cause of the issues.” The use of the genetic component of IQ has clearly screwed people groom ring awarded what they should have rightfully gotten. This is, of course, an example of environmental racism,

Parallels with the Waneta Hoyt case

The story of Big Lead and their denial of the deleterious effects of lead paint reminds me of another similar issue: That of the case of Waneta Hoyt and SIDS. This parallels this case like this: Waneta Hoyt was killing her children by suffocating them, and a SIDS researcher—Alfred Steinschneider—claimed that the cause was genetic, ignoring all signs that Waneta was the cause of her children’s death. This is represented by genes (Steinschneider) and environment (Waneta). In the case of the current discussion, this is represented by genes (Big Lead and their attempts to pinpoint genetic causes for what lead did) and environment (actual environmental effects of lead on the developing child).

There is a pattern in these two cases: Looking to genetic causes and bypassing the actual environmental cause. Genetic factors are represented by Steinschneider and Big Lead while they ignore or downplay the actual environmental causes (represented by Waneta Hoyt and the actual effects of lead on developing children). Selective focus like this, quite clearly, did lead to ignoring or overlooking crucial information. In the Hoyt case, it lead to the death of a few infants which could have been prevented (if Steinschneider didn’t have such tunnel vision for his genetic causation for SIDS). In the Big Lead case, NL Industries and it’s witnesses pointed to genetic factors or individual behaviors as the culprit for the causes of the negative behaviors and cognitive deficits for the children. In both cases, confirmation bias was thusly a main culprit.

Conclusion

The search for genetic causes and understanding certain things to be genetically caused has caused great harm. Big Lead and its attempted downplaying of the deleterious effects of lead paint while shifting blame to genetic factors reminds us that genetic reductionism and determinism is still here, and that corporate entities will attempt to use genetic arguments in order to ensure their interests are secured. Just as in the Waneta Hoyt case, where a misdirection towards genetic factors cloaked the true cause of the harm (which was environmental), the focus on genetics by Big Lead shifted shifted attention away from the true cause and put it on causes coming from inside the body.

The lobbying efforts of Big Lead damage for countless numbers of children and their families. And by hiding with genetic arguments, trying to deflect the harmful effects of what their leaded paint did to children, they chose to go to the genes argument, pushed by hereditarians as an explanation of the IQ gap. This, as well, is yet more evidence that IQ tests (along with association studied to identify causal genes for IQ) should be banned since they have clearly caused harms to people, in this case, not getting what they should have gotten by winning a court case that they should have won. Big Lead successfully evaded accountability here, and they did so with genetic reductionism.

Quite obviously, the KKI knowingly placed black families into homes that they knew had lead paint for experimentation purposes and this was highly unethical. This shows the environmental injustice and environmental racism, where vulnerable populations are used for nothing more than an experiment without their consent and knowledge. The parallels here are obvious in how Big Lead attempted to divert blame from the environmental effects of lead and implicate genetic factors and familial histories of retardation. This strategy is mirrored in the Waneta Hoyt case. Although Steinschneider didn’t have any kind of biases like Big Lead have, he did have a bias in attempting to pinpoint a genetic cause for SIDS which left him unable to see that the cause of the deaths was the mother of the children, Waneta Hoyt.

When Will Bo Winegard Understand What Social Constructivists Say and Don’t Say About Race?: Correcting Bo’s Misconceptions About Social Constructivism

3200 words

For years it seems as if Bo Winegard—former professor (his contract was not renewed)—does not understand the difference between social constructivism about race (racial constructivism refers to the same thing as social constructivism about race so I will be using these two terms interchangeably) and biological realism about race. It seems like he assumes that racial constructivists say that race isn’t real. But if that were true, how would it make sense to call race a social concept if it doesn’t exist? It also seems to me like he is saying that social constructs aren’t real. Money and language are social constructs, too, so does that mean they aren’t real? It doesn’t make sense to say that.

Quite obviously, if X is a social convention, then X is real, albeit a social reality. So if race is a social convention, then race is real. However, Bo’s ignorance to this debate is seen perfectly with this quote from a recent article he wrote:

Some conservative social constructionists and culture-only theorists (i.e., non race realists) have pushed back against the excesses of racial progressivism

In this article, Bo (rightly) claims that hereditarianism is a subset of race realism (I make a distinction between psychological and racial hereditarianism). But where Bo goes wrong is in not making the distinction between biological and social racial realism, as for example Kaplan and Winther (2014) did. Kaplan and Winther’s paper is actually the best look into how the concepts of bio-genomic cluster/racial realism, socialrace, and biological racial realism are realist positions about race. The AAPA even stated a few years back that “race has become a social reality that structures societies and how we experience the world. In this regard, race is real, as is racism, and both have real biological consequences. Membership in socially-defined (racial) groups can have real-life impacts themselves even if there are no biological races in the human species (Graves, 2015). That is: The social can and does become biological (meaning that the social can manifest itself in biology).

Bo’s ignorance can be further seen with this quote:

there is an alternative position: race realism, which argues that people use the concept of race for the same reason that they use the concept of species or sex

And he also wrote a tweet while explaining his “moderate manifesto”, again pushing the same misconception that social constructivists about race aren’t realists about race:

(2) Modern elite discourse contends that race is illusory, a kind of reified figment of our social imagination. BUT, it also contends that we need to promote race-conscious policies to rectify past wrongs. Race is unreal. But some “races” deserve benefits.

… I should note that race, like many other categories, is partially a social construct. But that does not mean that it’s not real.

Bo makes claims like “race is real”, as if social constructivists don’t think that race is real. That’s the only way for social constructivists to be about race. I think Bo is talking about racial anti-realists like Joshua Glasgow, who claim that race is neither socially nor biologically real. But social constructivists and biological racial realists (this term gets thorny since it could refer to a “realist” like Rushton or Jensen, who have no solid grounding in their belief in race or it could refer to philosophers like Michael Hardimon (like his minimalist/populationist, racialist and socialrace concepts) and Quayshawn Spencer (his Blumenbachian partitions), are both realists about race, but in different ways. Kaplan and Winther’s distinctions are good to set these 2 different camps a part and distinguish between them while still accepting that they are both realists.

I don’t think Bo realizes the meandering he has been doing for years discussing this concept. Race is partially a social construct, but race is real (which hereditarians believe), yet social constructivists about race are talking about something. They are talking about a referent, where a referent for race here is a property name for a set of human population groups (Spencer, 2019). The concept of race refers to a social something, thus it is real since society makes it real. Nothing in that entails that race isn’t real. If Bo made the distinction between biological and social races, then he would be able to say that social constructivists about race believe that race is real (they are realists about race as a social convention), but they are anti-realists about biological races.

Social constructivists are anti-realists about biological races, but they hold that the category RACE is a social and not biological construct. I addressed this issue in my article on white privilege:

If race doesn’t exist, then why does white privilege matter?

Lastly, those who argue against the concept of white privilege may say that those who are against the concept of white privilege would then at the same time say that race—and therefore whites—do not exist so, in effect, what are they talking about if ‘whites’ don’t exist because race does not exist? This is of course a ridiculous statement. One can indeed reject claims from biological racial realists and believe that race exists and is a socially constructed reality. Thus, one can reject the claim that there is a ‘biological’ European race, and they can accept the claim that there is an ever-changing ‘white’ race, in which groups get added or subtracted based on current social thought (e.g., the Irish, Italians, Jews), changing with how society views certain groups.

Though, it is perfectly possible for race to exist socially and not biologically. So the social creation of races affords the arbitrarily-created racial groups to be in certain areas on the hierarchy of races. Roberts (2011: 15) states that “Race is not a biological category that is politically charged. It is a political category that has been disguised as a biological one.” She argues that we are not biologically separated into races, we are politically separated into them, signifying race as a political construct. Most people believe that the claim “Race is a social construct” means that “Race does not exist.” However, that would be ridiculous. The social constructivist just believes that society divides people into races based on how we look (i.e., how we are born) and then society divides us into races on the basis of how we look. So society takes the phenotype and creates races out of differences which then correlate with certain continents.

So, there is no contradiction in the claim that “Race does not exist” and the claim that “Whites have certain unearned privileges over other groups.” Being an antirealist about biological race does not mean that one is an antirealist about socialraces. Thus, one can believe that whites have certain privileges over other groups, all the while being antirealists about biological races (saying that “Races don’t exist biologically”).

Going off Kaplan and Winther’s distinction, there are 3 kinds of racial realism: bio-genomic/cluster realism, biological racial realism, and social constructivism about race (socialraces). These three different racial frameworks have one thing in common: they accept the reality of race, but they merely disagree as to the origins of racial groups. Using these distinctions set forth by Kaplan and Winther, we can see how best to view different racial concepts and how to apply them in real life. Kaplan and Winther (2014: 1042) “are conventionalists about bio-genomic cluster/race, antirealists about biological race, and realists about social race.” And they can state this due to the distinction they’ve made between different kinds of racial realism. (Since I personally am a pluralist about race, all of these could hold under certain contexts, but I do hold that race is a social construct of a biological reality, pushing Spencer’s argument.)

Biological race isn’t socialrace

These 2 race concepts are distinct, where one talks about how race is viewed in the social realm while the other talks about how race is viewed in the biological realm. There is of course the view that race is a social construct of a biological reality (a view which I hold myself).

Biological race refers to the categorization of humans based on genetic traits and ancestry (using this definition, captures the bio-genomic/cluster realism as well). So if biological and socialrace were equivalent concepts, then it would mean that genetic differences that define different racial groups would map onto similar social consequences. So if two people from different racial groups are biologically different, then their social experiences and opportunities in society should also differ. Obviously, the claim here is that if two concepts are identical, then they should produce the same outcomes. But socialrace isn’t merely a reflection of biological race (as race realists like Murray, Jensen, Lynn, an Rushton hold to). Socialrace has been influenced by cultural, social, and political factors and so quite obviously it is socially constructed (constructed by society, the majority believe that race is real, so that makes it real).

There are of course social inequalities related to different racial groups. People of different socialraces find themselves treated differently while experiencing different things, and this then results in disparities in opportunity, privileges and disadvantages. These disparities can be noted in healthcare, criminal justice, education, employment and housing—anywhere individuals from a group can face systemic barriers and discrimination. People from certain racial groups may experience lower access to quality education, reduced job opportunities, increased chance of coming into contact with the law, how they are given healthcare, etc. Sin s these disparities persist even after controlling for SES, this shows how race is salient in everyday life.

The existence of social disparities and inequalities between racial groups shows that socialrace cannot be determined by biological factors. It is instead influenced by social constructs, historical context, and power dynamics in a society. So differences in societal consequences indicate the distinction between the two concepts. Socialrace isn’t a mere extension of biological race. Biological differences can and do exist between groups. But it is the social construction and attribution of meaning to these differences that have shaped the lived experiences and outcomes of individuals in society. So by recognizing that race isn’t solely determined by biology, and by recognizing that socialrace isn’t biological race and biological race isn’t social race (i.e., they are different concepts), we can have a better, more nuanced take on how we socially construct differences between groups. (Like that of “Hispanics/Latinos.) Having said all that, here’s the argument:

(P1) If biological and socialrace are the same, then they would have identical consequences in society regarding opportunities, privileges, and disadvantages

(P2) But there are disparities in opportunities, privileges, and disadvantages based on socialrace in various societies.

(C) So biological race and socialrace aren’t the same.

The claim that X is a social construct doesn’t mean that X is imaginary, fake, or unreal. Social constructs have real, tangible impacts on society and individuals’ lives which influences how they are perceived and treated. Further, historical injustices and systemic racism are more evidence that race is a social construct.

Going back to the distinction between three types of racial realism from Kaplan and Winther, what they phrase biological racial realism (Kaplan and Winther, 2014: 1040-1041):

Biological racial realism affirms that a stable mapping exists between the social groups identified as races and groups characterized genomically or, at least, phenomically.2 That the groups are biological populations explains why the particular social groups, and not others, are so identified. Furthermore, for some, but by no means all, biological racial realists, the existence of biological populations (and of the biologically grounded properties of their constituent individuals) explains and justifies at least some social inequalities (e.g., the “hereditarians”; Jensen 1969; Herrnstein and Murray 1995; Rushton 1995; Lynn and Vanhanen 2002). [This is like Hardimon’s racialist race/socialrace distinction.]

Quite obviously, distinguishing between the kinds of racial realism here points out that biological racial realists are of the hereditarian camp, and so race is an explanation for certain social inequalities (IQ, job market outcomes, crime). Social constructivists, however, have argued that what explains these differences is the social, historical, and political factors (see eg The Color of Mind).

(P1) If race is a social construct, then racial categories are not fixed and universally agreed-upon.

(P2) If racial categories are not fixed and universally agreed-upon, then different societies can define race differently.

(C1) So if race is a social construct, then different societies can define race differently.

(P3) If different societies can define race differently, then race lacks an inherent and biological basis.

(P4) Different societies do define race differently (observation of diverse racial classifications worldwide).

(C2) Thus, race lacks and inherent and biological basis.

(P5) If race lacks and inherent and biological basis, then race is a social construct.

(P6) Race lacks an inherent and biological basis.

(C3) Therefore, race is a social construct.

Premise 1: The concept of race varies across place and time. For example, we once had the one drop rule, which stated that any amount of “black blood” makes one black irregardless of their appearance or background. But Brazil has a more fluid approach to racial classification, like pardo and mullato. So this shows that racial categories aren’t fixed and universally agreed-upon, since race concepts in the US and Brazil are different. It also shows that race categories can change on the basis of social and cultural context and, in the context of Brazil, the number of slaves that were transported there.

Premise 2: Racial categories were strictly enforced in apartheid South Africa and people were placed into groups based on arbitrary criteria. Though this classification system differs from the caste system in India, where caste distinctions are based on a social hierarchy, not racial characteristics, which shows how different societies have different concepts of identity and social distinctions (how and in what way to structure their societies). So Conclusion 1 then follows: The variability in racial categorization across societies shows that the concept of race is not fixed, but is shaped by societal norms and beliefs.

Premise 3: Jim Crow laws and the one drop rule show how racial categorization can shift depending on the times and what is currently going on in the society in question. The example of Jim Crow laws show that historical context and social norms dictated racial classification and the boundary between races. Again, going back to the example of Brazil is informative to explain the point. The Brazilian racial system encompasses a larger range of racial groups which were influenced by slavery and colonization and the interactions between European, African, and indigenous peoples. So this shows how racial identity can and has been shaped by historical happenstance along with the intermixing or racial and ethnic groups.

Premise 4: As I already explained, Brazil and South Africa recognize a broader range of racial categories due to their historical circumstances and diverse social histories and dynamics. So Conclusion 2 follows, since these examples show that race doesn’t have a fixed, inherent and objective biological basis; it shows that race is shaped by social, historical, and cultural contexts.

Premise 5: So due to the variability in racial categorization historically and today, and the changing of racial boundaries in the past. For instance, Irish and Italian Americans were seen as different races in the 1900s, but over time as they assimilated into American society, racial categories began to blur and they then became part of the white race. Racial categories in Brazil are based on how the person is perceived, which leads to multiple different racial groups. Apartheid South Africa has 4 classifications: White, Black, Colored (mixed race) and Indian. These examples highlight the fact that based on changing social conventions and thought, how race can and does change with the times based on what is currently going on in the society in question. This highlights the fluid nature of racial categories. The argument up until this point has provided evidence for Premise 6, so Conclusion 3 follows: race is a social construct. Varying racial categories in different societies across time and place, the absence of an objective biological basis to race, along with the influence of historical, cultural, and social factors all point to the conclusion that race is a social construct.

Conclusion

Quite obviously, there is a distinction between biological and social race. The distinction is important, if we want to reject a concept of biological race while still stating that race is real. But hereditarians like Bo, it seems, don’t understand the distinction at hand. Bo, at least, isn’t alone in being confused about race concepts and their entailments. Murray (2020) stated:

Advocates of “race is a social construct” have raised a host of methodological and philosophical issues with the cluster analyses. None of the critical articles has published a cluster analysis that does not show the kind of results I’ve shown.

But social constructivists need to do no such thing. Why would they need to produce a cluster analysis that shows opposite results to what Murray claims? This shows that Murray doesn’t understand what social constructivists believe. Of course, equating race and biology is the MO of hereditarians, since they argue that some social inequalities between races are due to genetic differences between races.

Social constructivists talking about something real—a dynamic and evolving concept which has profound consequences for society. Rejecting the concept of biological races doesn’t entail that the social constructvist doesn’t believe that human groups don’t differ genetically. It does entail that the genetic diversity found in humans groups doesn’t necessitate the establishment of rigid and fixed racial categories. So in rejecting biological racial realism, social constructivists embrace the view that racial classifications are fixated by social, cultural, and historical contingencies. The examples I’ve given in this article show how racial categorization has changed based on time and place, and this is because race is a social construct.

I should note that I am a pluralist about race, which is “the view that there’s a plurality of natures and realities for race in the relevant linguistic context” (Spencer, 2019: 27), so “there is no such thing as a global meaning of ‘race’ (2019 : 43). The fact that there is no such thing as a global meaning of race entails that different societies across time and place will define racial groups differently, which we have seen, and so race is therefore a social construct (and I claim it is a social construct of a biological reality). Hereditarians like Bo don’t have this nuance, due to their apparent insistence that social constructivists are a kind of anti-realist about race as a whole. This claim, as I’ve exhaustively shown, is false. Different concepts of race can exist with each other based on context, leading to complex and multifaceted understandings of race and it’s place in society.

The second argument I formalized quite obviously gets at the distinction between biological and social racial realism shows the distinction between the two—I have defended the premises and have given examples on societies in different time and place that had different views of the racial groups in this country. This, then, shows that race is a social construct and that social constructivists about race are realists about race—since they are talking about something that has a referent.

Mind, Culture, and Test Scores: Dualistic Experiential Constructivism’s Insights into Social Disparities

2450 words

Introduction

Last week I articulated a framework I call Dualistic Experiential Constructivism (DEC). DEC is a theoretical framework which draws on mind-body dualism, experiential learning, and constructivism to explain human development, knowledge acquisition, and the formation of psychological traits and mind. In the DEC framework, knowledge construction and acquisition are seen as due to a dynamic interplay between individual experiences and the socio-cultural contexts that they occur in. It has a strong emphasis on the significance of personal experiences, interacting with others, shaping cognitive processes, social understanding and the social construction of knowledge by drawing on Vygotsky’s socio-historical theory of learning and development, which emphasizes the importance of cultural tools and the social nature of learning. It recognizes that genes are not sufficient for psychological traits, but necessary for them. It emphasizes that the manifestation of psychological traits and mind are shaped by experiences, interactions between the socio-cultural-environmental context.

My framework is similar to some other frameworks, like constructivism, experiential learning theory (Kolb) (Wijnen-Meyer et al, 2022), social constructivism, socio-cultural theory (Vygotsky), relational developmental systems theory (Lerner and Lerner, 2019) and ecological systems theory (Bronfenbrenner, 1994).

DEC shares a key point with constructivism—that of rejecting passive learning and highlight the importance of the learner’s active engagement in the construction of knowledge. Kolb’s experiential learning theory proposes that people learn best through direct experiences and reflecting on those experiences, while DEC emphasizes the fact significance of experiential learning in shaping one’s cognitive processes and understanding of knowledge. DEC also relies heavily on Vygotsky’s socio-historical theory of learning and development, where both the DEC and Vygotsky’s theory emphasize the role of socio-cultural factors in shaping human development along with the construction of knowledge. Vygotsky’s theory also highlights the importance of social interaction, cultural and psychological tools and historical contexts, which DEC draws from. Cognitive development and knowledge arise from dynamic interactions between individuals and their environment while also acknowledging the reciprocal influences between the individual and their social context. (This is how DEC can also be said to be a social constructivist position.) DEC is also similar to Uri Bronfenbrenner’ecological systems theory, which emphasizes the influence of multiple environmental systems on human development. With DEC’s focus on how individuals interact with their cultural contexts, it is therefore similar to ecological systems theory. Finally, DST shares similarities with Learner’s relational developmental systems theory focusing on interactions, genes as necessary but not sufficient causes for the developing system, rejecting reductionism and acknowledging environmental and cultural contexts in shaping human development. They are different in the treatment of mind-body dualism and the emphasis on cultural tools in shaping cognitive development and knowledge acquisition.

Ultimately, DEC posits that individuals actively construct knowledge through their engagement with the world, while drawing upon their prior experiences, interactions with others and cultural resources. So the socio-cultural context in which the individual finds themselves in plays a vital role in shaping the nature of learning experiences along with the construction of meaning and knowledge. Knowing this, how would race, gender, and class be integrated into the DEC and how would this then explain test score disparities between different classes, men and women, and races?

Social identities and test score differences: The impact of DEC on gender, race and class discrepancies

Race, class, and gender can be said to be social identities. Since they are social identities, they aren’t inherent or fixed characteristics in individuals, they are social categories which influence an individual’s experiences, opportunities, and interaction within society. These social identities are shaped by cultural, historical, and societal factors which intersect in complex ways, leading to different experiences.

When it comes to gender, it has been known that boys and girls have different interests and so they have different knowledge basis. This has been evidenced since Terman specifically constructed his test to eliminate differences between men and women in his Stanford-Binet, and also evidenced by the ETS changing the SAT to reflect these differences between men and women (Rosser, 1989; Mensh and Mensh, 1991). So when it comes to the construction of knowledge and the engagement with the world, an individual’s gender influences the way they perceive the world, and interpret social dynamics and act in social situations. There is also gendered test content, as Rosser (1989) shows for the SAT. Thus, the concept of gender in society influences test scores since men and women are exposed to different kinds of knowledge; the fact that there are “gendered test items” (items that reflect or perpetuate gender biases, stereotypes or assumptions in its presentation).

But men and women have negligible differences in full-scale IQ, so how can DEC work here? It’s simple: men are better spatially and women are better verbally. Thus, by choosing which items they want on the test, test constructors can build the conclusions they want into the test. DEC emphasizes socio-cultural influences on knowledge exposure, stating that unique socio-cultural and historical experiences and contexts influences one’s knowledge acquisition. Cultural/social norms and gendered socialization can also shape one’s interests and experiences, which would then influence knowledge production. Further, test content could have gender bias (as Rosser, 1989 pointed out), and subjects that either sex are more likely to have interest in could have skewed answer outcomes (as Rosser showed). Stereotype threat is also another thing that could influence this, with one study conceptualizing stereotype threat gender as being responsible for gender differences in advanced math (Spencer, Steele, and Quinn, 1999). Although stereotype threat affects different groups in different ways, one analysis showed empirical support “for mediators such as anxiety, negative thinking, and mind-wandering, which are suggested to co-opt working memory resources under stereotype threat” (Pennington et al, 2016). Lastly, intersectionality is inherent in DEC. Of course the experiences of a woman from a marginalized group would be different from the experiences of a woman from a privileged group. So these differences could influence how gender intersects with other identities when it comes to knowledge production.

When it comes to racial differences in test scores, DEC would emphasis the significance of understanding test score variations as reflecting multifaceted variables resulting from the interaction of cultural influences, experiential learning, societal contexts and historical influences. DEC rejects the biological essentialism and reductionism of hereditarianism and their claims of innate, genetic differences in IQ—it contextualizes test score differences. It views test scores as dynamic outcomes, which are influenced by social contexts, cultural influences and experiential learning. It also highlights cultural tools as mediators of knowledge production which would then influence test scores. Language, communication styles, educational values and other cultural resources influence how people engage with test content and respond to test items. Of course, social interactions play a large part in the acquisition of knowledge in different racial groups. Cultural tools are shared and transmitted through social interactions within racial communities. Historical legacies and social structures could impact access to cultural tools along with educational opportunities that would be useful to score well on the test, which then would affect test performance. Blacks and whites are different cultural groups, so they’re exposed to different kinds of knowledge which then influences their test scores.

Lastly, we come to social class. People from families in higher social strata benefit from greater access to educational resources—along with enriching experiences—like attending quality pre-schools and having access to educational materials, materials that are likely to be in the test items on the test. The early learning experiences then set the foundation for performing well on standardized tests. Lower class people could have limited access to these kinds of opportunities, which would impact their readiness and therefore performance on standardized tests. Cultural tools and language also play a pivotal role in shaping class differences in test scores. Parents of higher social class could is language and communication patterns that could potentially contribute to higher test scores. Conversely, lower social classes could have lack of exposure to the specific language conventions used in test items which would then influence their performance. Social interactions also influence knowledge production. Higher social classes foster discussions and educational discourses which support academic achievement, and also the peer groups in would also provide additional academic support and encouragement which would lend itself to higher test scores. On the other hand, lower class groups have limited academic support along with fewer opportunities for social interactions which are conducive to learning the types of items and structure of the test. It has also been shown that there are SES disparities in language acquisition due to the home learning environment, and this contributes to the achievement gap and also school readiness (Brito, 2017). Thus, class dictates if one is or is not ready for school due to their exposure to language in their home learning environment. Therefore, in effect, IQ tests are middle-class knowledge tests (Richardson, 2001, 2022). So one who is not exposed to the specific, cultural knowledge on the test wouldn’t score as well as someone who is. Richardson (1999; cf, Richardson, 2002) puts this well:

So relative acquisition of relevant background knowledge (which will be closely associated with social class) is one source of the elusive common factor in psychometric tests. But there are other, non-cognitive, sources. Jensen seems to have little appreciation of the stressful effects of negative social evaluation and systematic prejudice which many children experience every day (in which even superficial factors like language dialect, facial appearance, and self-presentation all play a major part). These have powerful effects on self concepts and self-evaluations. Bandura et al (1996) have shown how poor cognitive self-efficacy beliefs acquired by parents become (socially) inherited by their children, resulting in significant depressions of self-expectations in most intellectual tasks. Here, g is not a general ability variable, but one of ‘self-belief’.

…

Reduced exposure to middle-class cultural tools and poor cognitive self-efficacy beliefs will inevitably result in reduced self-confidence and anxiety in testing situations.

…

In sum, the ‘common factor’ which emerges in test performances stems from a combination of (a) the (hidden) cultural content of tests; (b) cognitive self-efficacy beliefs; and (c) the self-confidence/freedom-from-anxiety associated with such beliefs. In other words, g is just an mystificational numerical surrogate for social class membership. This is what is being distilled when g is statistically ‘extracted’ from performances. Perhaps the best evidence for this is the ‘Flynn effect,’ (Fkynn 1999) which simply corresponds with the swelling of the middle classes and greater exposure to middle-class cultural tools. It is also supported by the fact that the Flynn effect is more prominent with non-verbal than with verbal test items – i.e. with the (covertly) more enculturated forms.

I can also make this argument:

(1) If children of different class levels have experiences of different kinds with different material, and (2) if IQ tests draw a disproportionate amount of test items from the higher classes, then (3) higher class children should have higher scores than lower-class children.

The point that ties together this analysis is that different groups are exposed to different knowledge bases, which are shaped by their unique cultural tools, experiential learning activities, and social interactions. Ultimately, these divergent knowledge bases are influenced by social class, race, and gender, and they play a significant role in how people approach educational tests which therefore impacts their test scores and academic performance.

Conclusion

DEC offers a framework in which we can delve into to explain how and why groups score differently on academic tests. It recognizes the intricate interplay between experiential learning, societal contexts, socio-historical contexts and cultural tools in shaping human cognition and knowledge production. The part that the irreducibility of the mental plays is pivotal in refuting hereditarian dogma. Since the mental is irreducible, then genes nor brain structure/physiology can explain test scores and differences in mental abilities. In my framework, the irreducibility of the mental is used to emphazies the importance of considering subjective experiences, emotions, conscious awareness and the unique perspectives of individuals in understanding human learning.

Using DEC, we can better understand how and why races, social classes and men and women score differently from each other. It allows us to understand experiential learning and how groups have access to different cultural and psychological tools in shaping cognitive development which would then provide a more nuanced perspective on test score differences between different social groups. DEC moves beyond the rigid gene-environment false dichotomy and allows us to understand how groups score differently, while rejecting hereditarianism and explaining how and why groups score differently using a constructivist lens, since all human cognizing takes place in cultural contexts, it follows that groups not exposed to certain cultural contexts that are emphasized in standardized testing may perform differently due to variations in experiential learning and cultural tools.

In rejecting the claim that genes cause or influence mental abilities/psychological traits and differences in them, I am free to reason that social groups score differently not due to inherent genetic differences, but as a result of varying exposure to knowledge and cultural tools. With my DEC framework, I can explore how diverse cultural contexts and learning experiences shape psychological tools. This allows a deeper understanding of the dynamic interactions between the individual and their environment, emphasizing the role of experiential learning and socio-cultural factors in knowledge production. Gene-environment interactions and the irreducibility of the mental allow me to steer clear of genetic determinist explanations of test score differences and correctly identity such differences as due to what one is exposed to in their lives. In recognizing G-E interactions, DEC acknowledges that genetic factors are necessary pre-conditions for the mind, but genes alone are not able to explain how mind arises due to the irreducibility principle. So by considering the interplay between genes and experiential learning in different social contexts, DEC offers a more comprehensive understanding of how individuals construct knowledge and how psychological traits and mind emerge, steering away from genetically reductionistic approaches to human behavior, action, and psychological traits.

I also have argued how mind-body dualism and developmental systems theory refute hereditarianism, thus framework I’ve created is a further exposition which challenges traditional assumptions in psychology, providing a more holistic and nuanced understanding of human cognition and development. By incorporating mind-body dualism, it rejects the hereditarian perspective of reducing psychology and mind to genes and biology. Thus, hereditarianism is discredited since it has a narrow focus on genetic determinism/reductionism. It also integrates developmental systems theory, where development is a dynamic process influenced by multiple irreducible interactions between the parts that make up the system along with how the human interacts with their environment to acquire knowledge. Thus, by addressing the limitations (and impossibility) of hereditarian genetic reductionism, my DEC framework provides a richer framework for explaining how mind arises and how people acquire different psychological and cultural tools which then influence their outcomes and performance on standardized tests.

Walter Lippmann’s Critique of IQ Tests: On Lippmann’s Prescient Observations

2100 words

Introduction

One of the first critics of IQ tests after they were brought to America and used by the US army was journalist Walter Lippmann. Lippmann was very prescient with some of his argumentation against IQ, making similar anti-measurement arguments to anti-IQ-ists today. Although he was arguing against the “army intelligence tests” (the alpha and beta along with the Stanford-Binet), his criticisms hold even today and for any so-called IQ test since they are “validated” on their agreement with other tests (that weren’t themselves validated). He rightly noted that the test items are chosen arbitrarily (and that the questions chosen reflected the test constructor’s biases), and that the test isn’t a measure at all but a sorter of sorts, which in effect classifies people. This is similar to what Garrison (2009) argued in his book A Measure of Failure. He also argued that “IQ” isn’t like length or weight, which is what Midgley (2018) argued and also what Haier (2014, 2018) stated about IQ test scores—they are not like inches, liters, or grams.

Lippmann’s critique of IQ

Lippmann got it right in one major way—he stated that IQ tests results give the illusion of measurement because the results “are expressed in numbers.” However, measurement is much more complex than that—there needs to be a specified measured object, object of measurement and measurement unit for X to be a measure, and if there isn’t then X isn’t a measure. Lippmann stated that Terman couldn’t demonstrate that he was “measuring intelligence” (McNutt, 2013: 10).

Because the results are expressed in numbers, it is easy to make the mistake of thinking that the intelligence test is a measure like a foot rule or a pair of scales. It is, of course, a quite different sort of measure. For length and weight are qualities which men have learned how to isolate no matter whether they are found in an army of soldiers, a heap of bricks, or a collection of chlorine molecules. Provided the footrule and the scales agree with the arbitrarily accepted standard foot and standard pound in the Bureau of Standards at Washington they can be used with confidence. But “intelligence” is not an abstraction like length and weight; it is an exceedingly complicated notion which nobody has as yet succeeded in defining.

He then invents puzzles which can be employed quickly and with little apparatus, that will according to his best guess test memory, ingenuity, definition and the rest. He gives these puzzles to a mixed group of children and sees how children of different ages answer them. Whenever he finds a puzzles that, say, sixty percent of the twelve year old children can do, and twenty percent of the eleven year olds, he adopts that test for the twelve year olds. By a great deal of fitting he gradually works out a series of problems for each age group which sixty percent of his children can pass, twenty percent cannot pass and, say, twenty percent of the children one year younger can also pass. By this method he has arrived under the Stanford-Binet system at a conclusion of this sort: Sixty percent of children twelve years old should be able to define three out of the five words: pity, revenge, charity, envy, justice. According to Professor Terman’s instructions, a child passes this test if he says that “pity” is “to be sorry for some one”; the child fails if he says “to help” or “mercy.” A correct definition of “justice” is as follows: “It’s what you get when you go to court”; an incorrect definition is “to be honest.”

A mental test, then is established in this way: The tester himself guesses at a large number of tests which he hopes and believes are tests of intelligence. Among these tests those finally are adopted by him which sixty percent of the children under his observation can pass. The children whom the tester is studying select his tests.

…

What then do the tests accomplish? I think we can answer this question best by starting with an illustration. Suppose you wished to judge all the pebbles in a large pile of gravel for the purpose of separating them into three piles, the first to contain the extraordinary pebbles, the second normal pebbles, and the third the insignificant pebbles. You have no scales. You first separate from the pile a much smaller pile and pick out one pebble which you guess is the average. You hold it in your left hand and pick up another pebble in your right hand. The right pebble feels heavier. You pick up another pebble. It feels lighter. You pick up a third. It feels still lighter. A fourth feels heavier than the first. By this method you can arrange all the pebbles from the smaller pile in a series running from the lightest to the heaviest. You thereupon call the middle pebble the standard pebble, and with it as a measure you determine whether any pebble in the larger pile is sub-normal, a normal or a supernormal pebble.

This is just about what the intelligence test does. It does not weigh or measure intelligence by any objective standard. It simply arranges a group of people in a series from best to worst by balancing their capacity to do certain arbitrarily selected puzzles, against the capacity of all the others. The intelligence test, in other words, is fundamentally an instrument for classifying a group of people. It may also be an instrument for measuring their intelligence, but of that we cannot be at all sure unless we believe that M. Binet and Mr. Terman and a few other psychologists have guessed correctly but, as we shall see later, the proof is not yet at hand.

The intelligence test, then, is an instrument for classifying a group of people, rather than “a measure of intelligence.” People are classified within a group according to their success in solving problems which may or may not be tests of intelligence.

Even though Lippmann was writing over 100 years ago in 1922, his critiques have stood the test of time. Being one of the first critics of hereditarian dogman, he took on Terman in the pages of The New Republic, and I don’t think Lippmann’s main arguments were touched—and 100 years later, it looks to be more of the same. Still, as shown above, even some psychologists admit that certain things that are true of physical measures aren’t true of IQ.

Jansen (2010: 134) noted that “Lippmann vehemently opposed introducing I.Q. tests into the schools on democratic grounds, contending that it would lead to an intellectual caste system.” Lippmann and other environmentalists in the 1920s sought to understand variation in IQ as due to environment, and that all individuals had the same “biological capacity” for “intelligence” (Mancuso and Dreisinger, 1969). (They also state that a physiological intelligence was the “logical outcome” of the scientific materialism of the 19th century, a point I have made myself.) Not only is the concept of “IQ/intelligence” arbitrary, it is indeed used as an ideological tool (Gonzelez, 1979; Richardson, 2017).

The fact of the matter is, IQ-ists back then—and I would say now as well—were guilty of the naming fallacy (Conley, 1986):

Walter Lippmann had exposed most of its critical weaknesses in a series of articles in the New Republic in 1922. He emphasized the fundamental point that “intelligence is not an abstraction like length and weight; it is an exceedingly complicated notion which nobody has yet succeeded in defining.”33 Then, in 1930, C.C. Brigham, one of the most influential scientific proponents of eugenics, recanted. Accepting Lippmann’s point, he accused himself and his colleagues of a “naming fallacy” which allowed them “to slide mysteriously from the score in the test to the hypothetical faculty suggested by the name given to the test.”’34 He repudiated the whole concept of national and racial comparisons based on intelligence test scores, and then, in what is surely the most remarkable statement I have ever read in a scientific publication, concluded, “One of the most pretentious of these comparative racial studies—the writer’s own—was without foundation.”35

Finally, returning to the test items being arbitrary and reflecting the test constructor’s biases, this was outright admitted by Terman. He stated that he created a “norm intelligent” group which led to the “developing [of] an exclusion-inclusion criteria that favored the [US born white men of north European descent], test developers created a norm “intelligent” (Gersh, 1987, p.166) population “to differentiate subjects of known superiority from subjects of known inferiority” (Terman, 1922, p. 656) (Bazemore-James, Shinaprayoon, and Martin, 2017). This, of course, proves Lippmann’s point about these tests—the test’s constructors assumed ahead of time who is or is not “intelligent” and then devise tests with specific item content to get their desired distribution—Terman outright admitted this. Lippmann was 100 percent right about that issue.

Conclusion

Lippmann’s critiques of IQ, although they were written 100 years ago, can still be made today. Lippmann got much right in his critiques of Terman and other hereditariansm psychologists, and his claim that if you can’t define something then you can’t measure it is valid. Although Lippmann’s warnings on the abuse of IQ testing were not heeded, the fact of the matter is, Lippmann was in the right in this debate 100 years ago. One of Lippmann’s main points—that test items are chosen arbitrarily and chosen to agree with a priori biases—still holds true today, since the Stanford-Binet is now on its 5th edition and since it is “validated” on its “agreement” with older versions of the Stanford-Binet, this assumption is carried into the modern day. (Do note that Terman assumed that men and women should have similar IQ scores and so devised his test to reflect this, and this shows, again, that the previous biased that the test constructors held were then built into the test. So this shows that what chat be built in can be built out.)