Home » bio-ecological model

Category Archives: bio-ecological model

The Answer to Hereditarianism is Developmental Systems Theory

4150 words

Introduction

It is claimed that genes (DNA sequences) have a special, privileged role in the development of all traits. But once we understand what genes do and their role in development, then we will understand that the role ascribed to genes by gene-selectionists and hereditarians outright fails. Indeed, the whole “nature vs nurture” debate implies that genes determine traits and that it’s possible to partition the relative contributions to traits in a genetic and environmental way. This, however, is far from reality (like heritability estimates).

DST isn’t a traditional scientific theory—it is more a theoretical perspective on developmental biology, heredity, and evolution, though it does make some general predictions (Griffiths and Hochman, 2015). But aspects of it have been used to generate novel predictions in accordance with the extended evolutionary synthesis (Laland et al, 2015).

Wilson (2018: 65) notes six themes of DST:

Joint determination by multiple causes

Development is a process of multiple interacting sources.

Context sensitivity and contingency

Development depends on the current state of the organism.

Extended inheritance

An organism inherits resources from the environment in addition to genes.

Development as a process of construction

The organism helps shape its own environment, such as the way a beaver builds a dam to raise the water level to build a lodge.

Distributed control

Idea that no single source of influence has central control over an organism’s development.

Evolution as construction

The evolution of an entire developmental system, including whole ecosystems of which organisms are parts, not just the changes of a particular being or population.

Genes (DNA sequences) as resources and outcomes

Hereditarians have a reductionist view of genes and what they do. Genes, to the hereditarian, are causes of not only development but of traits and evolution, too. However the hereditarian is sorely mistaken—there is no a priori justification for treating genes as privileged causes over and above other developmental resources (Noble, 2012). I take Noble’s argument there to mean that strong causal parity is true—where causal parity means that all developmental resources are on par with each other, with no other resource having primacy over another. They all need to “dance in tune” with the “music of life” to produce the phenotype, to borrow Noble’s (2006, 2017) analogy. Hereditarian dogma also has its basis in the neo-Darwinian Modern Synthesis. The modern synthesis has gotten causality in biology wrong. Genes are, simply put, passive, not active, causes:

Genes, as DNA sequences, do not of course form selves in any ordinary sense. The DNA molecule on its own does absolutely nothing since it reacts biochemically only to triggering signals. It cannot even initiate its own transcription or replication. … It would therefore be more correct to say that genes are not active causes; they are, rather, caused to give their information by and to the system that activates them. The only kind of causation that can be attributed to them is passive, much in the way a computer program reads and uses databases. (Noble, 2011)

These ideas, of course, are also against the claim that genes are blueprints or recipes, as Plomin (2018) claims in his most recent book (Joseph, 2022). This implies that they are context-independent; we have known for years that genes are massively context-sensitive. The line of argument that hereditarians push is that genes are context-insensitive, that is they’re context-independent. But since DNA is but one of the developmental resources the physiological system uses to create the phenotype, this claim fails. Genes are not causes on their own.

Behavioral geneticist and evolutionary psychologist J. P. Rushton (1997: 64) claims that a study shows that “genes are like blueprints or recipes providing a template for propelling development forward to some targeted endpoint.” That is, Rushton is saying that there is context-independent “information” in genes, and that genes, in essence, guide development toward a targeted endpoint. Noah Carl (2019) claims that the hereditarian hypothesis “states that these differences [in cognitive ability] are partly or substantially explained by genetics.” When he says the differences are “partly or substantially explained by genetics”, he’s talking about “cognitive ability” being caused by genes. The claim that genes cause (either partly or substantially) cognitive ability—and all traits, for that matter—fails and it fails since genes don’t do what hereditarians think they do. (Nevermind the conceptual reasons.) These claims are laughable, due to what Noble, Oyama, Moore and Jablonka and Lamb have argued. It is outright false that genes are like blueprints or recipes. Rushton’s is reductionist in a sociobiology-type way, while Plomin’s is reductionist in a behavioral genetic type way.

In The Dependent Gene, David Moore (2002: 81) talks about the context-dependency of genes:

Such contextual dependence renders untenable the simplistic belief that there are coherent, long-lived entities called “genes” that dictate instructions to cellular machinery that merely constructs the body accordingly. The common belief that genes contain context-independent “information”—and so are analogous to “blueprints” or “recipes”—is simply false.

Genes are always expressed in context and cannot be divorced from said context, like hereditarians attempt using heritability analyses. Phenotypes aren’t “in the genes”, they aren’t innate. They develop through the lifespan (Blumberg, 2018).

Causal parity and hereditarianism

Hereditarianism can be said to be a form of genetic reductionism (and mind-brain identity). The main idea of reductionism is to reduce the whole to the sum of its parts and then analyze those parts. Humans (the whole) are made up of genes (the parts), so to understand human behavior, and humans as a whole, we must then understand genes, so the story goes.

Cofnas (2020) makes several claims regarding the hereditarian hypothesis and genes:

But if we find that many of the same SNPs predict intelligence in different racial groups, a risky prediction made by the hereditarian hypothesis will have passed a crucial test.

…

But if work on the genetics and neuroscience of intelligence becomes sufficiently advanced, it may soon become possible to give a convincing causal account of how specific SNPs affect brain structures that underlie intelligence (Haier, 2017). If we can give a biological account of how genes with different distributions lead to race differences, this would essentially constitute proof of hereditarianism. As of now, there is nothing that would indicate that it is particularly unlikely that race differences will turn out to have a substantial genetic component. If this possibility cannot be ruled out scientifically, we must face the ethical question of whether we ought to pursue the truth, whatever it may be.

Haier is a reductionist of not only the gene variety but the neuro variety—he attempts to reduce “intelligence” to genes and neurology (brain physiology). I have though strongly criticized the use of fMRI neuroimaging studies regarding IQ; cognitive localizations in the brain are untenable (Uttal, 2001, 2011) and this is because mind-brain identity is false.

Cofnas asks “How can we disentangle the effects of genes and environment?” and states the the behavioral geneticist has two ways—correlations between twins and adoptees and GWAS. Unfortunately for Cofnas, twin and adoption studies show no such thing (see Ho, 2013), most importantly because the EEA is false (Joseph, 2022a, b). GWAS studies are also fatally confounded (Janssens and Joyner, 2019) and PGS doesn’t show what behavioral geneticists need it to show (Richardson, 2017, 2022). The concept of “heritability” is also a bunk notion (Moore and Shenk, 2016). (Also see below for further discussion on heritability.) At the end of the day, we can’t do what the hereditarian needs to be done for their explanations to hold any water. And this is even before we look at the causal parity between genes and other developmental resources. Quite obviously, the hereditarian hypothesis is a gene-centered view, and it is of course a reductionist view. And since it is a reductionist, gene-centered view, it is then false.

Genetic, epigenetic, and environmental factors operate as a system to form the phenotype. Since this is true, therefore, both genetic and epigenetic determinism is false (also see Wagoner and Uller, 2015). It’s false because the genes one is born with, or develops with, don’t dictate or determine anything, especially not academic achievement as hereditarian gene-hunters would so gleefully claim. And one’s early experience need not dictate an expected outcome, since development is a continuous process. Although, that does not mean that environmental maladies that one experiences during childhood won’t have lasting effects into adulthood due to possibly affecting their psychology, anatomy or physiology.

The genome is responsive, that is, it is inert before it is activated by the physiological system. When we put DNA in a petri dish, it does nothing. It does nothing because DNA cannot be said to be a separate replicator from the cell (Noble, 2018). So genes don’t do anything independent of the context they’re in; they do what they do DUE TO the context they’re in. This is like Gottlieb’s (2007) probabilistic epigenesis, where the development of an organism is due to the coaction of irreducible bidirectional biological and environmental influences. David S. Moore, in The Developing Genome: An Introduction to Behavioral Epigenetics states this succinctly:

Genes—that is, DNA segments—are always influenced by their contexts, so there is never a perfect relationship between the presence of a gene and the ultimate appearance of a phenotype. Genes do not determine who we become, because nongenetic factors play critical roles in trait development; genes do what they do at least in part because of their contexts.

What he means by “critical roles in trait development” is clear if one understands Developmental Systems Theory (DST). DST was formulated by Susan Oyama (1985) in her landmark book “The Ontogeny of Information. In the book, she argues that nature and nurture are not antagonistic to each other, they are cooperative in shaping the development of organisms. Genes do not play a unique informational role in development. Thus, nature vs. nurture is a false dichotomy—it’s nature interacting with nurture, or GxE. This interactionism between nature and nurture—genes and environment—is a direct refutation of hereditarianism. What matters is context, and the context is never independent from what is going on during development. Genes aren’t the units of selection, the developmental system is, as Oyama explains in Evolution’s Eye:

If one must have a “unit” of evolution, it would be the interactive developmental system: life cycles of organisms in their niches. Evolution would then be change in the constitution and distribution of these systems (Oyama, 2000b)

Genes are important, of course, for the construction of the organism—but so are other resources. Without genes, there would be nothing for the cell to read to initiate transcription. However, without the cellular environment, we wouldn’t have DNA. Lewontin puts this wonderfully in the introduction to the 2000 edition of Ontogeny:

There are no “gene actions” outside environments, and no “environmental actions” can occur in the absence of genes. The very status of environment as a contributing cause to the nature of an organism depends on the existence of a developing organism. Without organisms there may be a physical world, but there are no environments. In like manner no organisms exist in the abstract without environments, although there may be naked DNA molecules lying in the dust. Organisms are the nexus of external circumstances and DNA molecules that make these physical circumstances into causes of development in the first place. They become causes only at their nexus, and they cannot exist as causes except in their simultaneous action. That is the essence of Oyama’s claim that information comes into existence only in the process of Ontogeny. (2000, 15-16)

Genes aren’t causes on their own, they are resources for development. And being resources for development, they have no privileged level of causation over other developmental resources, such as “methylation patterns, membrane templates, cytoplasmic gradients, centrioles, nests, parental care, habitats, and cultures” (Griffiths and Stotz, 2018). All of these things, and more of course, need to work in concert with each other.

Indeed, this is the causal parity argument—the claim that genes aren’t special developmental resources, that they are “on par” with other developmental resources (Griffiths and Gray, 1994; Griffiths and Stotz, 2018). Gene knockout studies show that the loss of a gene can be compensated by other genes—which is known as “genetic compensation.” None of the developmental resources play a more determinative role than other resources (Noble, 2012; Gamma and Liebrenz, 2019). This causal parity, then, has implications for thinking about trait ontogeny.

The causal parity of genes and other developmental factors also implies that genes cannot constitute sufficient causal routes to traits, let alone provide complete explanations of traits. Full-blown explanations will integrate various kinds of causes across different levels of organizational hierarchy, and across the divide between the internal and the external. The impossibly broad categories of nature vs. nurture that captured the imagination of our intellectual ancestors a century ago are no longer fit for the science of today. (Gamma and Liebrenz, 2019)

Oyama (2000a 40) articulates the casual parity thesis like this:

What I am arguing for here is a view of causality that gives formative weight to all operative influences, since none is alone sufficient for the phenomenon or for any of its properties, and since variation in any or many of them may or may not bring about variation in the result, depending on the configuration of the whole.

While Griffiths and Hochman (2015) formulate it like this:

The ‘parity thesis’ is the claim that if some role is alleged to be unique to nucleic acids and to justify relegating nongenetic factors to a secondary role in explaining development, it will turn out on closer examination that this role is not unique to nucleic acids, but can be played by other factors.

Genes are necessary pre-conditions for trait development, just as the other developmental resources are necessary pre-conditions for trait development. No humans without genes—this means that genes are necessary pre-conditions. If genes then humans—this implies that genes are sufficient for human life, but they are but one part of what makes humans human, when all of the interactants are present, then the phenotype can be constructed. So all of the developmental resources interacting are sufficient.

The nature vs. nurture dichotomy can be construed in such a way that they are competing explanations. However, we now know that the dichotomy is a false one and that the third way—interactionism—is how we should understand development. Despite hereditarian protestations, DST/interactionism refutes their claims. The “information” in the genes, then, cannot explain how organisms are made, since information is constructed dialectically between the resources and the system. There are a multiplicity of causal factors that are involved in this process, and genes can’t be privileged in this process. Thus the phrase “genetic causation” isn’t a coherent concept. Moreover, DNA sequences aren’t even coherent outside of cellular context (Noble, 2008).

Griffiths and Stotz (2018) put the parity argument like this:

In The Ontogeny of Information Oyama pioneered the parity argument, or the ‘parity thesis’, concerning genetic and environmental causes in development (see also Griffiths and Gray 1994; Griffiths and Gray 2005; Griffiths and Knight 1998; Stotz 2006; Stotz and Allen 2012). Oyama relentlessly tracked down failures of parity of reasoning in earlier theorists. The same feature is accorded great significance when a gene exhibits it, only to be ignored when a non-genetic factor exhibits it. When a feature thought to explain the unique importance of genetic causes in development is found to be more widely distributed across developmental causes, it is discarded and another feature is substituted. Griffiths and Gray (1994) argued in this spirit against the idea that genes are the sole or even the main source of information in development. Other ideas associated with ‘parity’ are that the study of development does not turn on a single distinction between two classes of developmental resources, and that the distinctions useful for understanding development do not all map neatly onto the distinction between genetic and non-genetic.

Shea (2011) tries to argue that genes do have a special role, and that is to transport information. Genes are, of course, inherited, but so is every other part of the system (resources). Claiming that there is information “in the genes” is tantamount to saying that there is a special role for DNA in development. But, as I hope will be clear, this claim fails due to the nature of DNA and its role in development.

This line of argument leads to one clear conclusion—genes are followers, they are not leaders; most evolution begins with environmentally-mediated phenotypic change, and then genetic changes occur (West-Eberhard, 2003). Ho and Saunders (1979) state that variation in organisms is constructed during development due to an interaction between genetic and non-genetic factors. That is, they follow what is needed to do by the developmental system, they aren’t leading development, they are but one party in the whole symphony of development. Development can be said to be irreducible, so we cannot reduce development to genes or anything else, as all interactants need to be present for development to be carried out. Since genes are activated by other factors, it is incoherent to talk of “genetic causes.” Genes affect the phenotype only when they are expressed, and other resources, too, affect the phenotype this is, ultimately, an argument genes against as blueprints, codes, recipes, or any other kind of flowery language one can used to impute what amounts to intention to inert DNA.

Even though epigenetics invalidates all genetic reductionism (Lerner and Overton, 2017), genetic reductionist ideas still persist. They give three reasons why genetic reductionist ideas still persist despite the conceptual, methodological, and empirical refutations. (1) Use of terms like “mechanism”, “trait”, and “interaction”; (2) constantly shifting to other genes once their purported “genes for” traits didn’t workout; and (3) they “buried opponents under repetitive results” (Panofsky, quoted in Lerner and Overton, 2017). The fact of the matter is, there are so many lines of evidence and argument that refute hereditarian claims that it is clear the only reason why one would still be a hereditarian in this day and age is that they’re ignorant—that is racist.

Genes, that is, are servants, not masters, of the development of form and individual differences. Genes do serve as templates for proteins: but not under their own direction. And, as entirely passive strings of chemicals, it is logically impossible for them to initiate and steer development in any sense. (Richardson, 2016)

DST and hereditarian behavioral genetics

I would say that DST challenges three claims from hereditarian behavioral genetics (HBG hereafter):

(1) The claim that we can neatly apportion genes and environment into different causes for the ontogeny of traits;

(2) Genes are the only thing that are inherited and that genes are the unit of selection and a unique—that is, special and privileged cause over and above other resources;

(3) That genes vs environment, blank skate vs human nature, are a valid dichotomy.

(1) HBG needs to rely on the attempting to portion out causes of traits into gene and environmental causes. The heritability statistic presumes additivity, thy is, it assumes no interaction. This is patently false. Charney (2016) gives the example of schizophrenia—it is claimed that 50 percent of the heritability of schizophrenia is accounted for by 8000 genes, which means that each SNP accounts for 1/8000 of the half of the heritability. This claim is clearly false, as genetics aren’t additive, and the additivity assumption precludes the interaction of genes with genes, and environment, which create new interactive environments. Biological systems are not additive, they’re interactive. Heritability estimates, therefore, are attempts at dichotomizing what is not dichitomizable (Rose, 2005).

An approach that partitions variance into independent main effects will never resolve the debate because, by definition, it has no choice but to perpetuate it. (Goldhaber, 2012)

This approach, of course, is the approach that attempts to partition variance into G and E components. The assumption is that G and E are additive. But as DST theorists have argued for almost 40 years, they are not additive, they are interactive and so not additive, therefore heritability estimates fail on conceptual grounds (as well as many others). Heritability estimates have been—and continue to today—been at the heart of the continuance of the nature vs nurture distinction, the battle, if you will. But if we accept Oyama’s causal parity argument—and due to the reality of how genes work in the system, I see no reason why we shouldn’t—then we should reject hereditarianism. Hereditarians have no choice but to continue the false dichotomy of nature vs nurture. Their “field” depends on it. But despite the fact that the main tool for the behavioral geneticist lies on false pretenses (twin and adoption studies), they still try to show that heritability estimates are valid in explaining trait variation (Segalowitz, 1999; Taylor, 2006, 2010).

(2) More than genes are inherited. Jablonka and Lamb (2005) argue that there are four dimensions—interactants—to evolution: genetic, epigenetic, behavioral, and symbolic. They show the context-dependency of the genome, meaning that genotype does not determine phenotype. What does determine the phenotype, as can be seen from the discussion here, is the interacting of developmental resources in development. Clearly, there are many other inheritance systems other than genes. There is also the fact that the gene as popularly conceived does not exist—so it should be the end of the gene as we know it.

(3) Lastly, DST throws out the false dichotomy of genes and environment, nature and nurture. DST—in all of its forms—rejects the outright false dichotomy of nature vs nurture. They are not in a battle with each other, attempting to decide who is to be the determining factor in trait ontogeny. They interact, and this interaction is irreducible. So we can’t reduce development to genes or environment (Moore, 2016) Development isn’t predetermined, it’s probabilistic. The stability of phenotypic form isn’t found in the genes (Moore and Lickliter, 2023)

Conclusion

Genes are outcomes, not causes, of evolution and they are not causes of trait ontogeny on their own. The reality is that strong causal parity is true, so genes cannot be regarded as a special developmental resource from other resources—that is, genes are not privileged resources. Since they are not privileged resources, we need to, then, dispense with any and all concepts of development that champion genes as being the leader of the developmental process. The system is, not genes, with genes being but one of many of the interactants that shape phenotypic development.

By relying on the false narrative that genes are causes and that they cause not only our traits but our psychological traits and what we deem “good” and “bad”, we would then be trading social justice for hereditarianism (genetic reductionism).

These recommended uses of bad science reinforce fears of institutionalized racism in America and further the societal marginalization of minority groups; these implications of their recommendations are never publicly considered by those who promulgate these flawed extensions of counterfactual genetic reductionism. (Lerner, 2021)

Such [disastrous societal] applications can only rob people of life chances and destroy social justice. Because developmental science has the knowledge base to change the life course trajectories of people who are often the targets of genetic reductionist ideas, all that remains to eradicate genetic reductionism from scientific discussion is to have sufficient numbers of developmental scientists willing to proclaim loudly and convincingly that the naked truth is that the “emperor” (of genetic reductionism) has no clothes. (Lerner, 2021: 338)

Clearly, hereditarians need the nature vs nurture debate to continue so they can push their misunderstandings about genes ans psychology. However, given our richer understanding of genes and how they work, we now know that hereditarianism is untenable, and DST conceptions of the gene and development as a whole have led us to that conclusion. Lerner (2017) stated that as soon as the failure of one version of genetic reductionism is observed, another one pious up—making it like a game of whack-a-mole.

The cure to hereditarian genetic reductionism is a relational developmental systems (RDS) model. This model has its origins with Uri Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory (Bronfenbrenner and Ceci, 1994; Ceci, 1996; Patel, 2011; Rosa and Tudge, 2013. Development is about the interacting and relation between the individual and environment, and this is where RDS theory comes in. Biology, physiology, culture, and history are studied to explain human development (Lerner, 2021). Hereditarian ideas cannot give us anything like what models derived from developmental systems ideas can. An organism-environment view can lead to a more fruitful, and the organism and environment are inseparable (Jarvilehto, 1998; Griffiths and Gray, 2002). And it is for these reasons, including many, many more, that hereditarian genetic reductionist ideas should become mere sand in the wind.

Having said all that, here’s the argument:

P1: If hereditarianism is true, then strong causal parity is false.

P2: Strong causal parity is true.

C: Therefore hereditarianism must be false.

Knowledge, Culture, Logic, and IQ

5050 words

… what IQ tests actually assess is not some universal scale of cognitive strength but the presence of skills and knowledge structures more likely to be acquired in some groups than in others. (Richardson, 2017: 98)

For the past 100 years, the black-white IQ gap has puzzled psychometricians. There are two camps—hereditarians (those who believe that individual and group differences in IQ are due largely to genetics) and environmentalists/interactionists (those who believe that individual and group differences in IQ are largely due to differences in learning, exposure to knowledge, culture and immediate environment).

Knowledge

However, one of the most forceful arguments for the environmentalist (i.e., that the cause for differences in IQ are due to the cultural and social environment; note that an interactionist framework can be used here, too) side is one from Fagan and Holland (2007). They show that half of the questions on IQ tests had no racial bias, whereas other problems on the test were solvable with only a specific type of knowledge – knowledge that is found specifically in the middle class. So if blacks are more likely to be lower class than whites, then what explains lower test scores for blacks is differential exposure to knowledge – specifically, the knowledge to complete the items on the test.

But some hereditarians say otherwise – they claim that since knowledge is easily accessible for everyone, then therefore, everyone who wants to learn something will learn it and thus, the access to information has nothing to do with cultural/social effects.

A hereditarian can, for instance, state that anyone who wants to can learn the types of knowledge that are on IQ tests and that they are widely available everywhere. But racial gaps in IQ stay the same, even though all racial groups have the same access to the specific types of cultural knowledge on IQ tests. Therefore, differences in IQ are not due to differences in one’s immediate environment and what they are exposed to—differences in IQ are due to some innate, genetic differences between blacks and whites. Put into premise and conclusion form, the argument goes something like this:

P1 If racial gaps in IQ were due specifically to differences in knowledge, then anyone who wants to and is able to learn the stuff on the tests can do so for free on the Internet.

P2 Anyone who wants to and is able to learn stuff can do so for free on the Internet.

P3 Blacks score lower than whites on IQ tests, even though they have the same access to information if they would like to seek it out.

C Therefore, differences in IQ between races are due to innate, genetic factors, not any environmental ones.

This argument is strange. One would have to assume that blacks and whites have the same access to knowledge—we know that lower-income people have less access to knowledge in virtue of the environments they live in. For instance, they may have libraries with low funding or bad schools with teachers who do not care enough to teach the students what they need to succeed on these standardized tests (IQ tests, the SAT, etc are all different versions of the same test). (2) One would have to assume that everyone has the same type of motivation to learn what amounts to answers for questions on a test that have no real-world implications. And (3) the type of knowledge that one is exposed to dictates what one can tap into while they are attempting to solve a problem. All three of these reasons can cascade in causing the racial performance in IQ.

Familiarity with the items on the tests influences a faster processing of information, allowing one to correctly identify an answer in a shorter period of time. If we look at IQ tests as tests of middle-class knowledge of skills, and we rightly observe that blacks are lower class than whites who are more likely to be middle class, then it logically follows that the cause of differences in IQ between blacks and whites are cultural – and not genetic – in origin. This paper – and others – solves the century-old debate on racial IQ differences – what accounts for differences in IQ scores is differential exposure to knowledge. Claiming that people have the same type of access to knowledge and, thusly, won’t learn it if they won’t seek it out does not make sense.

Differing experiences lead to differing amounts of knowledge. If differing experiences lead to differing amounts of knowledge, and IQ tests are tests of knowledge—culturally-specific knowledge—then those who are not exposed to the knowledge on the test will score lower than those who are exposed to the knowledge. Therefore, Jensen’s Default Hypothesis is false (Fagan and Holland, 2002). Fagan and Holland (2002) compared blacks and whites on for their knowledge of the meaning of words, which are highly “g”-loaded and shows black-white differences. They review research showing that blacks have lower exposure to words and are therefore unfamiliar with certain words (keep this in mind for the end). They mixed in novel words with previously-known words to see if there was a difference.

Fagan and Holland (2002) picked out random words from the dictionary, then putting them into a sentence to attempt to give the testee some context. They carried out five experiments in all, and each one showed that, when equal opportunity was given to the groups, they were “equal in knowledge” (IQ). So, whites were more likely to know the items more likely to be found on IQ tests. Thus, there were no racial differences between blacks and whites when looked at from an information-processing point of view. Therefore, to expain racial differences in IQ, we must look to differences in the cultural/social environment. Fagan (2000) for instance, states that “Cultures may differ in the types of knowledge their members have but not in how well they process. Cultures may account for racial differences in IQ.”

The results of Fagan and Holland (2002) are completely at-ends with Jensen’s Default Hypothesis—that the 15-point gap in IQ is due to the same environmental and cultural factors that underlie individual differences in the group. However, as Fagan and Holland (2002: 382) show that:

Contrary to what the default hypothesis would predict, however, the within racial group analyses in our study stand in sharp contrast to our between racial group findings. Specifically, individuals within a racial group who differed in general knowledge of word meanings also differed in performance when equal exposure to the information to be tested was provided. Thus, our results suggest that the average difference of 15 IQ points between Blacks and Whites is not due to the same genetic and environmental factors, in the same ratio, that account for differences among individuals within a racial group in IQ.

Exposure to information is critical, in fact. For instance, Ceci (1996) shows that familiarity with words dictates speed of processing to use in identifying the correct answer to the problem. In regard to differences in IQ, Ceci (1996) does not deny the role of biology—indeed, it’s a part of his bio-ecological model of IQ, which is a theory that postulates the development of intelligence as an interaction between biological dispositions and the environment in which those dispositions manifest themselves. Ceci (1996) does note that there are biological constraints on intelligence, but that “… individual differences in biological constraints on specific cognitive abilities are not necessarily (or even probably) directly responsible for producing the individual differences that have been reported in the psychometric literature.” That such potentials, though may be “genetic” in origin, of course, does not license the claim that genetic factors contribute to variance in IQ. “Everyone may possess them to the same degree, and the variance may be due to environment and/or motivations that led to their differential crystallization.” (Ceci, 1996: 171)

Ceci (1996) also further shows that people can differ in intellectual performance due to 3 things: (1) the efficiency of underlying cognitive potentials that are relevant to the cognitive ability in question; (2) the structure of knowledge relevant to the performance; and (3) contextual/motivational factors relevant to crystallize the underlying potentials gained through one’s knowledge. Thus, if one is lacking in the knowledge of the items on the test due to what they learned in school, then the test will be biased against them since they did not learn the relevant information on the tests.

Cahan and Cohen (1989) note that nine-year-olds in fourth grade had higher IQs than nine-year-olds in third grade. This is to be expected, if we take IQ scores as indices of—cultural-specific—knowledge and skills and this is because fourth-graders have been exposed to more information than third-graders. In virtue of being exposed to more information than their same-age cohort in different grades, they then score higher on IQ tests because they are exposed to more information.

Cockroft et al (2015) studied South African and British undergrads on the WAIS-III. They conclude that “the majority of the subtests in the WAIS-III hold cross-cultural biases“, while this is “most evident in tasks which tap crystallized, long-term learning, irrespective of whether the format is verbal or non-verbal” so “This challenges the view that visuo-spatial and non-verbal tests tend to be culturally fairer than verbal ones (Rosselli and Ardila, 2003)”.

IQ tests “simply reflect the different kinds of learning by children from different (sub)cultures: in other words, a measure of learning, not learning ability, and are merely a redescription of the class structure of society, not its causes … it will always be quite impossible to measure such ability with an instrument that depends on learning in one particular culture” (Richardson, 2017: 99-100). This is the logical position to hold: for if IQ tests test class-specific type of knowledge and certain classes are not exposed to said items, then they will score lower. Therefore, since IQ tests are tests of a certain kind of knowledge, IQ tests cannot be “a measure of learning ability” and so, contra Gottfredson, ‘g’ or ‘intelligence’ (IQ test scores) cannot be called “basic learning ability” since we cannot create culture—knowledge—free tests because all human cognizing takes place in a cultural context which it cannot be divorced from.

Since all human cognition takes place through the medium of cultural/psychological tools, the very idea of a culture-free test is, as Cole (1999) notes, ‘a contradiction in terms . . . by its very nature, IQ testing is culture bound’ (p. 646). Individuals are simply more or less prepared for dealing with the cognitive and linguistic structures built in to the particular items. (Richardson, 2002: 293)

Heine (2017: 187) gives some examples of the World War I Alpha Test:

1. The Percheron is a kind of

(a) goat, (b) horse, (c) cow, (d) sheep.

2. The most prominent industry of Gloucester is

(a) fishing, (b) packing, (c) brewing, (d) automobiles.

3. “There’s a reason” is an advertisement for

(a) drink, (b) revolver, (c) flour, (d) cleanser.

4. The Knight engine is used in the

(a) drink, (b) Stearns, (c) Lozier, (d) Pierce Arrow.

5. The Stanchion is used in

(a) fishing, (b) hunting, (c) farming, (d) motoring.

Such test items are similar to what are on modern-day IQ tests. See, for example, Castles (2013: 150) who writes:

One section of the WAIS-III, for example, consists of arithmetic problems that the respondent must solve in his or her head. Others require test-takers to define a series of vocabulary words (many of which would be familiar only to skilled-readers), to answer school-related factual questions (e.g., “Who was the first president of the United States?” or “Who wrote the Canterbury Tales?”), and to recognize and endorse common cultural norms and values (e.g., “What should you do it a sale clerk accidentally gives you too much change?” or “Why does our Constitution call for division of powers?”). True, respondents are also given a few opportunities to solve novel problems (e.g., copying a series of abstract designs with colored blocks). But even these supposedly culture-fair items require an understanding of social conventions, familiarity with objects specific to American culture, and/or experience working with geometric shapes or symbols. [Since this is questions found on the WAIS-III, then go back and read Cockroft et al, 2015 since they used the British version which, of course, is similar.]

If one is not exposed to the structure of the test along with the items and information on them, how, then, can we say that the test is ‘fair’ to other cultural groups (social classes included)? For, if all tests are culture-bound and different groups of people have different cultures, histories, etc, then they will score differently by virtue of what they know. This is why it is ridiculous to state so confidently that IQ tests—however imperfectly—test “intelligence.” They test certain skills and knowledge more likely to be found in certain groups/classes over others—specifically in the dominant group. So what dictates IQ scores is differential access to knowledge (i.e., cultural tools) and how to use such cultural tools (which then become psychological tools.)

Lastly, take an Amazonian people called The Pirah. They have a different counting system than we do in the West called the “one-two-many system, where quantities beyond two are not counted but are simply referred to as “many”” (Gordon, 2005: 496). A Pirah adult was shown an empty can. Then the investigator put six nuts into the can and took five out, one at a time. The investigator then asked the adult if there were any nuts remaining in the can—the man answered that he had no idea. Everett (2005: 622) notes that “Piraha is the only language known without number, numerals, or a concept of counting. It also lacks terms for quantification such as “all,” “each,” “every,” “most,” and “some.””

(hbdchick, quite stupidly, on Twitter wrote “remember when supermisdreavus suggested that the tsimane (who only count to s’thing like two and beyond that it’s “many”) maybe went down an evolutionary pathway in which they *lost* such numbers genes?” Riiiight. Surely the Tsimane “went down an evolutionary pathway in which they *lost* such numbers genes.” This is the idiocy of “HBDers” in action. Of course, I wouldn’t expect them to read the actual literature beyond knowing something basic (Tsimane numbers beyond “two” are known as “many”) and the positing a just-so story for why they don’t count above “two.”

Non-verbal tests

Take a non-verbal test, such as the Bender-Gestalt test. There are nine index cards which have different geometrical designs on them, and the testee needs to copy what he saw before the next card is shown. The testee is then scored on how accurate his recreation of the index card is. Seems culture-fair, no? It’s just shapes and other similar things, how would that be influenced by class and culture? One would, on a cursory basis, claim that such tests have no basis in knowledge structure and exposure and so would rightly be called “culture-free.” While the shapes that come on Ravens tests are novel, the rules governing them are not.

Hoffmann (1966) studied 80 children (20 Kickapoo Indians (KIs), 20 low SES blacks (LSBs), 20 low SES whites (LSWs), and 20 middle-class whites (MCWs)) on the Bender-Gestalt test. The Kickapoo were selected from 5 urban schools; 20 blacks from majority-black elementary schools in Oklahoma City; 20 whites in low SES areas of Oklahoma; and 20 whites from middle-schools in Oklahoma from majority-white schools. All of the children were aged 8-10 years of age and in the third grade, while all had IQs in the range of 90-110. They were matched on a whole slew of different variables. Hoffman (1966: 52) states “that variations in cultural and socio-economic background affect Bender Gestalt reproduction.”

Hoffman (1966: 86) writes that:

since the four groups were shown to exhibit no significant differences in motor, or perceptual discrimination ability it follows that differences among the four groups of boys in Bender Gestalt performance are assignable to interpretative factors. Furthermore, significant differences among the four groups in Bender performance illustrates that the Bender Gestalt test is indeed not a so called “culture-free” test.

Hoffman concluded that MCWs, KIs, LSBs, and LSWs did not differ in copying ability, nor did they differ significantly in discriminating in different phases in the Bender-Gestalt; there also was no bias in figures that had two of the different sexes on them. They did differ in their reproductions of Bender-Gestalt designs, and their differing performance can be, of course, interpreted differently by different people. If we start from the assumption that all IQ tests are culture-bound (Cole, 2004), then living in a different culture from the majority culture will have one score differently by virtue of having differing—culture-specific knowledge and experience. The four groups looked at the test in different ways, too. Thus, the main conclusion is that:

The Bender Gestalt test is not a “culture-free” test. Cultural and socio-economic background appear to significantly affect Bender Gestalt reproduction. (Hoffman, 1966: 88)

Drame and Ferguson (2017) and Dutton et al (2017) also show that there is bias in the Raven’s test in Mali and Sudan. This, of course, is due to the exposure to the types of problems on the items (Richardson, 2002: 291-293). Thus, their cultures do not allow exposure to the items on the test and they will, therefore, score lower in virtue of not being exposed to the items on the test. Richardson (1991) took 10 of the hardest Raven’s items and couched them in familiar terms with familiar, non-geometric, objects. Twenty eleven-year-olds performed way better with the new items than the original ones, even though they used the same exact logic in the problems that Richardson (1991) devised. This, obviously, shows that the Raven is not a “culture-free” measure of inductive and deductive logic.

The Raven is administered in a testing environment, which is a cultural device. They are then handed a paper with black and white figures ordered from left to right. Note that Abel-Kalek and Raven (2006: 171) write that Raven’s items “were transposed to read from right to left following the custom of Arabic writing.” So this is another way that the tests are biased and therefore not “culture-free.”) Richardson (2000: 164) writes that:

For example, one rule simply consists of the addition or subtraction of a figure as we move along a row or down a column; another might consist of substituting elements. My point is that these are emphatically culture-loaded, in the sense that they reflect further information-handling tools for storing and extracting information from the text, from tables of figures, from accounts or timetables, and so on, all of which are more prominent in some cultures and subcultures than others.

Richardson (1991: 83) quotes Keating and Maclean (1987: 243) who argue that tests like the Raven “tap highly formal and specific school skills related to text processing and decontextualized rule application, and are thus the most systematically acculturated tests” (their emphasis). Keating and Maclean (1987: 244) also state that the variation in scores between individuals is due to “the degree of acculturation to the mainstream school skills of Western society” (their emphasis). That’s the thing: all types of testing is biased towards a certain culture in virtue of the kinds of things they are exposed to—not being exposed to the items and structure of the test means that it is in effect biased against certain cultural/social groups.

Davis (2014) studied the Tsimane, a people from Bolivia, on the Raven. Average eleven-year-olds scored 78 percent or more of the questions correct whereas lower-performing individuals answered 47 percent correct. The eleven-year-old Tsimane, though, only answered 31 percent correct. There was another group of Tsimane who went to school and lived in villages—not living in the rainforest like the other group of Tsimane. They ended up scoring 72 percent correct, compared to the unschooled Tsimane who scored only 31 percent correct. “… the cognitive skills of the Tsimane have developed to master the challenges that their environment places on them, and the Raven’s test simply does not tap into those skills. It’s not a reflection of some kind of true universal intelligence; it just reflects how well they can answer those items” (Heine, 2017: 189). Thus, measures of “intelligence” are not an innate skill, but are learned through experience—what we learn from our environments.

Heine (2017: 190) discusses as-of-yet-to-be-published results on the Hadza who are known as “the most cognitively complex foragers on Earth.” So, “the most cognitively complex foragers on Earth” should be pretty “smart”, right? Well, the Hadza were given six-piece jigsaw puzzles to complete—the kinds of puzzles that American four-year-olds do for fun. They had never seen such puzzles before and so were stumped as to how to complete them. Even those who were able to complete them took several minutes to complete them. Is the conclusion then licensed that “Hadza are less smart than four-year-old American children?” No! As that is a specific cultural tool that the Hadza have never seen before and so, their performance mirrored their ignorance to the test.

Logic

The term “logical” comes from the Greek term logos, meaning “reason, idea, or word.” So, “logical reasoning” is based on reason and sound ideas, irrespective of bias and emotion. A simple syllogistic structure could be:

If X, then Y

X

∴ Y

We can substitute terms, too, for instance:

If it rains today, then I must bring an umbrella.

It’s raining today.

∴ I must bring an umbrella.

Richardson (2000: 161) notes how cross-cultural studies show that what is or is not logical thinking is not objective nor simple, but “comes in socially determined forms.” He notes how cross-cultural psychologist Sylvia Scribner showed some syllogisms to Kpelle farmers, which were couched in terms that were familiar to them. One syllogism given to them was:

All Kpelle men are rice farmers

Mr. Smith is not a rice farmer

Is he a Kpelle man? (Richardson, 2002: 162)

The individual then continuously replied that he did not know Mr. Smith, so how could he know whether or not he was a Kpelle man? Another example was:

All people who own a house pay a house tax

Boima does not pay a house tax

Does Boima own a house? (Richardson, 2000: 162)

The answer here was that Boima did not have any money to pay a house tax.

In regard to the first syllogism, Mr. Smith is not a rice farmer so he is not a Kpelle man. Regarding the second, Boima does not pay a house tax, so Boima does not own a house. The individual could give a syllogism that is something like:

All the deductions I can make are about individuals I know.

I do not know Mr. Smith.

Therefore I cannot make a deduction about Mr. Smith. (Richardson, 2000: 162)

They are using what are familiar terms to them, and so, they get the answer right for their culture based on the knowledge that they have. These examples, therefore, show that what can pass for “logical reasoning” is based on the time and place where it is said. The deductions the Kpelle made were perfectly valid, though they were not what the syllogism-designers had in mind. In fact, I would say that there are many—equally valid—ways of answering such syllogisms, and such answers will vary by culture and custom.

The bio-ecological framework, culture, and social class

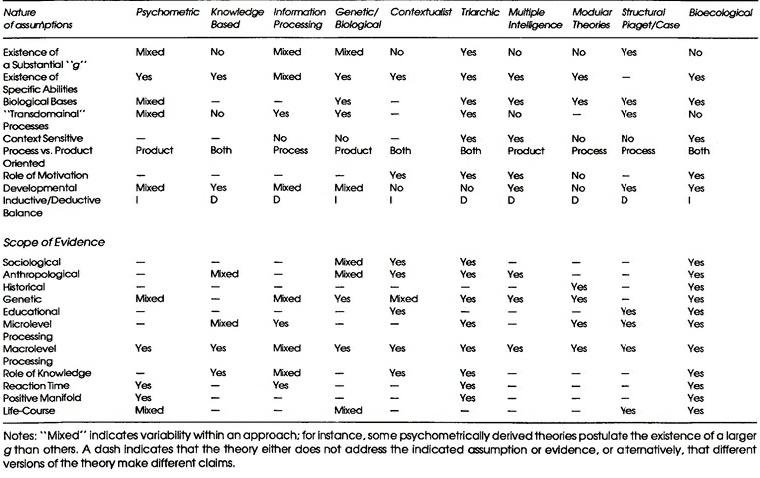

The bio-ecological model of Ceci and Bronfenbrenner is a model of human development that relies on gene and environment interactions. The model is a Vygotskian one—in that learning is a social process where the support from parents, teachers, and all of society play an important role in the ontogeny of higher psychological functioning. (For a good primer on Vygotskian theory, see Vygotsky and the Social Formation of Mind, Wertsch, 1985.) Thus, it is a model of human development that, most hereditarians would say, that “they use too.” Though this is of course, contested by Ceci who compares his bio-ecological framework with other theories (Ceci, 1996: 220, table 10.1):

Cognition (thinking) is extremely context-sensitive. Along with many ecological influences, individual differences in cognition are understood best with the bio-ecological framework which consists of three components: (1) ‘g’ doesn’t exist, but multiple cognitive potentials do; (2) motivational forces and social/physical aspects of a task or setting, how elaborate a knowledge domain is not only important in the development of the human, but also, of course, during testing; and (3) knowledge and aptitude are inseparable “such that cognitive potentials continuously access one’s knowledge base in the cascading process of producing cognitions, which in turn alter the contents and structure of the knowledge base” (Ceci, 1996: 123).

Block (1995) notes that “Blacks and Whites are to some extent separate cultural groups.” Sternberg (2004) defines culture as “the set of attitudes, values, beliefs and behaviors shared by a group of people, communicated from one generation to the next via language or some other means of communication.” In regard to social class—blacks and whites differ in social class (a form of culture), Richardson (2002: 298) notes that “Social class is a compound of the cultural tools (knowledge and cognitive and psycholingustic structures) individuals are exposed to; and beliefs, values, academic orientations, self-efficacy beliefs, and so on.” The APA notes that “Social status isn’t just about the cars we drive, the money we make or the schools we attend — it’s also about how we feel, think and act …” And the APS notes that social class can be seen as a form of culture. Since culture is a set of attitudes, beliefs and behaviors shared by a group of people, social classes, therefore, are forms of culture as different classes have different attitudes, beliefs and behaviors.

Ceci (1996 119) notes that:

large-scale cultural differences are likely to affect cognition in important ways. One’s way of thinking about things is determined in the course of interactions with others of the same culture; that is, the meaning of a cultural context is always negotiated between people of that culture. This, in turn, modifies both culture and thought.

While Manstead (2018) argues that:

There is solid evidence that the material circumstances in which people develop and live their lives have a profound influence on the ways in which they construe themselves and their social environments. The resulting differences in the ways that working‐class and middle‐ and upper‐class people think and act serve to reinforce these influences of social class background, making it harder for working‐class individuals to benefit from the kinds of educational and employment opportunities that would increase social mobility and thereby improve their material circumstances.

In fact, the bio-ecological model of human development (and IQ) is a developmental systems-type model. The types of things that go into the model are just like Richardson’s (2002) “sociocognitive affective nexus.” Richardson (2002) posits that the sources of IQ variation are mostly non-cognitive, writing that such factors include (pg 288):

(a) the extent to which people of different social classes and cultures have acquired a specific form of intelligence (or forms of knowledge and reasoning); (b) related variation in ‘academic orientation’ and ‘self-efficacy beliefs’; and (c) related variation in test anxiety, self-confidence, and so on, which affect performance in testing situations irrespective of actual ability

Cole (2004) concludes that:

Our imagined study of cross-cultural test construction makes it clear that tests of ability are inevitably cultural devices. This conclusion must seem dreary and disappointing to people who have been working to construct valid, culture-free tests. But from the perspective of history and logic, it simply confirms the fact, stated so clearly by Franz Boas half a century ago, that “mind, independent of experience, is inconceivable.”

The role of context is huge—and most psychometricians ignore it, as Ceci (1996: 107) quotes Bronfenbrenner (1989: 207) who writes:

It is a noteworthy feature of all preceding (cognitive approaches) that they make no reference whatsoever to the environment in which the person actually lives and grows. The implicit assumption is that the attributes in question are constant across place; the person carries them with her wherever she goes. Stating the issue more theoretically, the assumption is that the nature of the attribute does not change, irrespective of the context in which one finds one’s self.

Such contextual differences can be found in the intrinsic and extrinsic motivations of the individual in question. Self-efficacy, what one learns and how they learn it, motivation instilled from parents, all form part of the context of the specific individual and how they develop which then influences IQ scores (middle-class knowledge and skills scores).

(For a primer on the bio-ecological model, see Armour-Thomas and Gopaul-Mcnicel, 1997; Papierno et al, 2005; Bronfenbrenner and Morris, 2007; and O’Toole, 2016.)

Conclusion

If blacks and whites are, to some extent, different cultural groups, then they will—by definition—have differing cultures. So “cultural differences are known to exist, and cultural differences can have an impact on psychological traits [also in the knowledge one acquires which then is one part of dictating test scores] (see Prinz, 2014: 67, Beyond Human Nature). If blacks and whites are “separate cultural groups” (Block, 1995) and if they have different experiences by virtue of being cultural groups, then they will score differently on any test of ability (including IQ; see Fagan and Holland, 2002, 2007) as all tests of ability are culture-bound (see Cole, 2004).

1 Blacks and whites are different cultural groups.

2 If (1), then they will have different experiences by virtue of being different cultural groups.

3 So blacks and whites, being different cultural groups, will score differently on tests of ability, since they are exposed to different knowledge structures due to their different cultures.

So, what accounts for the intercorrelations between tests of “cognitive ability”? They validate the new test with older, ‘more established’ tests so “based on this it is unlikely that a measure unrelated to g will emerge as a winner in current practice … [so] it is no wonder that the intelligence hierarchy for different racial/ethnic groups remains consistent across different measures. The tests are highly correlated among each other and are similar in item structure and format” (Suzuki and Aronson, 2005: 321).

Therefore, what accounts for differences in IQ is not intellectual ability, but cultural/social exposure to information—specifically the type of information used in the construction of IQ tests—along with the test constructors attempting to construct new tests that correlate with the old tests, and so, they get the foregone conclusion of their being racial differences, for example, in IQ which they trumpet as evidence for a “biological cause”—but it is anything but: such differences are built into the test (Simon, 1997). (Note that Fagan and Holland, 2002 also found evidence for test bias as well.)

Thus, we should take the logical conclusion: what explains racial IQ differences are not biological factors, but environmental ones—specifically in the exposure of knowledge—along with how new tests are created (see Suzuki and . All human cognizing takes place in specific cultural contexts—therefore “culture-free tests” (i.e., tests devoid of cultural knowledge and context) are an impossibility. IQ tests are experience-dependent so if one is not exposed to the relevant experiences to do well in a testing situation, then they will score lower than they would have if they were to have the requisite culturally-specific knowledge to perform well on the test.