Home » Crime

Category Archives: Crime

Answering Common “Criticisms” of the Theory of African American Offending

4150 words

Introduction

Back in September I published an article arguing that since the theory of African American offending (TAAO) makes successful novel predictions and hereditarian explanations don’t, that we should accept the TAAO over hereditarian explanations. I then published a follow-up arguing that crime is bad and racism causes crime so racism is bad (and I also argued that stereotypes lead to self-fulfilling prophecies which then cause the black-white crime gap). The TAAO combines general strain theory, social control theory, social disorganization theory, learning theory, and low self control theory in order to better explain and predict crime in black Americans (Unnever, 2014).

For if a theory makes successful novel predictions, therefore that raises the probability that the theory is true. Take T1 and T2. T1 makes successful novel predictions. T2 doesn’t. So if T1 and T2 both try to explain the same things, then it’s only logical to accept T1 over T2. That’s the basis of the argument against hereditarian explanations of crime—the main ones all fail. Although some attempt at a theory has been made integrating hereditarian explanations (Ellis’ 2017 evolutionary neuroandrogenic theory), it doesn’t make any novel predictions. I’ve recently argued that that’s a death knell for hereditarian theories—there are no novel predictions of any kind for hereditarianism.

But since I published my comparison of the successes of the TAAO over hereditarian explanations, I’ve come across a few “responses” and they all follow the same trend: “What about Africa, Britain, and other places where blacks commit more crime? Why doesn’t racism cause other groups to commit more crime?” or “So blacks don’t have agency?” or “Despite what you argued against hereditarian explanations what about as-of-yet-to-be-discovered genes or hormonal influences that lead to higher crime in blacks compared to whites?” or “What about IQ and it’s relationship to crime?” or “What control groups are there for TAAO studies?” or “The black-white crime gap was lower during Jim Crow, how is this possible if the TAAO is true?” or “Unnever and Gabbidon are just making excuses for blacks with their TAAO” or “The so-called ‘novel predictions’ you reference aren’t novel at all.” I will answer these in turn and then provide a few more novel predictions of the TAAO.

“What about Africa, Britain, and other places where blacks commit more crime? Why doesn’t racism cause other groups to commit more crime?“

For some reason, TAAO detractors think this is some kind of knock-down questions for the TAAO and think that they disprove it. These are easily answered and they don’t threaten the theory at all.

For one, the theory of AFRICAN AMERICAN offending is irrelevant places that… Aren’t America. It’s a specific theory to explain why blacks commit crime at a higher rate IN AMERICA, therefore other countries are irrelevant. There would need to be a specific theory of crime for each of those places and contexts. So this question doesn’t hurt the theory. So going off of the first question, the answer to the second question also addresses it—it’s a theory that’s specifically formulated to explain and predict crime in a certain population in a certain place.

For two, why would a theory that’s specifically formulated to explain crime using the unique experiences of black Americans matter for other American groups? Blacks went through 400 years of slavery and then after that went through segregation and Jim Crow, so why would it mean anything that other groups face discrimination but then don’t have higher rates of crime compared to the average? Since the theory has specific focus on understanding the unique experiences and dynamics of crime in the black American population, it’s obvious that asking about other groups is just irrelevant. Other racial and ethnic groups aren’t the primary focus—since it aims to address historical and contemporary factors that lead to higher crime in the black American population. It’s in the name of the theory—so why would other racial groups matter? Unnever and Gabbidon (2011: 37) even explicitly addressed this point:

Our work builds upon the fundamental assumption made by Afrocentists that an understanding of black offending can only be attained if their behavior is situated within the lived experiences of being African American in a conflicted, racially stratified society. We assert that any criminological theory that aims to explain black offending must place the black experience and their unique worldview at the core of its foundation. Our theory places the history and lived experiences of African American people at its center. We also fully embrace the Afrocentric assumption that African American offending is related to racial subordination. Thus, our work does not attempt to create a “general” theory of crime that applies to every American; instead, our theory explains how the unique experiences and worldview of blacks in America are related to their offending. In short, our theory draws on the strengths of both Afrocentricity and the Eurocentric canon.

“So blacks don’t have agency?”

The theory doesn’t say that blacks lack agency (the capacity to make decisions and choices) at all. What the theory does say is that systemic factors like racism, socioeconomic disparities, and historical and contemporary marginalization can influence one’s choices and opportunities. So while individuals have agency, their choices are shaped by the social context they find themselves in. So if one has a choice to do X or ~X but they physical CAN’T do X, then they do not have a choice—they have an illusion of choice. The TAAO acknowledges that choices are constrained by poverty, racism, and social inequity. So while blacks—as all humans do—have agency, some “choices” are constrained, giving the illusion of choice. Thus, constraints should also be considered while analyzing why blacks offend more. This, too, is not a knock-down question.

“Despite what you argued against hereditarian explanations what about as-of-yet-to-be-discovered genes or hormonal influences that lead to higher crime in blacks compared to whites?”

Over the years I’d say I’ve done a good job of arguing against hereditarian theories of crime. (Like testosterone increasing aggression and blacks having higher levels of testosterone, the AR gene, and MAOA.) They’re just not tenable. The genetic explanation makes no sense. (Talk about disregarding agency…) But one response is that we could find some as-of-yet-to-be-discovered genes, gene networks, or neurohormonal influences which explain the higher crime rates in black Americans. This is just like the “five years away” claim that hereditarians love to use. We just need to wait X amount of years for the magic evidence, yet five years never comes since five years away is always five years away.

“What about IQ and it’s relationship to crime?”

Of course the IQ-ists love this question. The assumption is that lower IQ people are more likely to commit crime. So low is means more crime and high IQ means less crime. Ignoring the fact that IQ is not a cause of anything but an outcome of one’s life experiences, we know that the correlation between IQ and crime is -0.01 within family (Frisell, Pawitan, and Langstrom, 2012). So that, too, is an irrelevant question. The relationship just isn’t there.

“What control groups are there for TAAO studies?”

Other than the first question about why don’t other groups who experience racism commit more crime and what about blacks in other countries, this one takes the cake. The TAAO doesn’t need control groups in TAAO tests since it focuses specifically on understanding the unique factors that contribute to crime in America. So instead of comparing different racial or ethnic groups, the TAAO seeks to identify and analyze specific historical, social, and systemic factors which shape the experiences and behaviors of black Americans within the context of American society.

“The black-white crime gap was lower during Jim Crow, why? How is this possible if the TAAO is true?”

Between 1950 and 1963, non-whites made up 11 percent of the US population, 90 percent of which were black. In 1950 for whites the murder rate was 2 to 3 deaths per 100,000 while for non-whites the rate was 28 deaths per 100,000 (28 times the US average) which then fell to 21 per 100,000 in 1961 which was still about 8 times that of the white murder rate while the rate raised again between 1962 and 1964 (Langberg, 1967). Langan (1992) showed a steady increase in the incarcerated black population from 1926 (21 percent) to 1986 (44 percent). But demographic factors account for this, like increases in the sentencing of blacks, the increase in the black population, and increase on black arrest rates—furthermore, there is evidence for increased discrimination between 1973 and 1982 that would explain the 70s-80s incarceration rates (Harding and Winship, 2016). Harding and Winship also showed that differential population growth can account for one-third of the increase in the prison population difference while the rest can be accounted for by differences in sentencing and arrest rates between 1960 and 1980. So the black population increased more in states that had higher incarceration rates. Nonetheless, the TAAO isn’t supposed to retroactively explain trends.

Therefore, the disparity between whites and blacks remained, even pre-1964. This question, too, isn’t a knockdown for the TAAO either. These questions that are asked when one is provided with the successful novel predictions of the TAAO are just cope since hereditarian explanations don’t make novel predictions and their explanations fail (like the ENA theory).

“Unnever and Gabbidon are just making excuses for blacks with their TAAO.”

This is not what they’re doing with their theory at all. A theory is a well-substantiated explanation of some aspect of the natural word that’s based on observation, empirical data, and evidence. They provide testable hypotheses that can be empirically tested. They also make predictions based on their proposed explanations. Predictive capacity is a hallmark of scientific theories. And it’s clear and I’ve shown that the TAAO makes successful novel predictions. Therefore the ability of a theory to make predictions—especially risky and novel ones—lends credibility to the validity of the theory.

The claim that the TAAO is a mere excuse for black crime is ridiculous. Because if that’s true, then all theories of crime are excuses for criminal activity. The TAAO should be evaluated on its predictive power—it’s ability to make successful novel predictions. Claims that the theory is a mere “excuse” for black crime is ridiculous, especially since the theory makes successful novel predictions. It’s clearly a valuable framework for understanding black crime in America.

“The so-called ‘novel predictions’ you reference aren’t novel at all”

We need to understand what the TAAO actually is. It’s a theory of crime that considers the African American “peerless” worldview. “Peerless” means “incomparable.” They have the worldview they do due to the 400 years of slavery and oppression like Jim Crow laws and segregation. Therefore, to explain black crime we need to understand the peerless African American experience. That’s a main premise of the theory. So the TAAO has one main premise, and it’s from this premise that the predictions of the TAAO are derived.

The peerless worldview of African Americans This premise recognizes the unique historical, contemporary, social, and cultural experiences of African Americans including their experiences of racial discrimination, social marginalization, and racial identity. This premise, then, lays the key groundwork for understanding black crime. This core premise of the TAAO then centers the theory within the context of the African American experience. Each of the predictions below are derived from the core premise of the TAAO—that of the peerless worldview of African Americans without relying on the predictions as premises used for the construction of the theory. Each of the predictions follows from the core premise, and they reflect how the African American experiences of racial discrimination, social marginalization and racial identity influence their likelihood of experiencing racial discrimination. Unnever and Gabbidon gave many arguments and references that this is indeed the case. The predictions, then, weren’t used as premise to construct the TAAO but they indeed are derived from—indeed they emerge from—the foundational experiences of African Americans and then serve as testable hypotheses which are derived from that understanding.

Thus, the predictions follow from the TAAO and they are derived from the foundational premise of the TAAO, without being used in the construction of the theory itself, qualifying as novel predictions according to Musgrave (1988): “a predicted fact is a novel fact for a theory if it was not used to construct that theory — where a fact is used to construct a theory if it figures in the premises from which that theory was deduced” and Beerbower: “the purpose of science is to enable accurate predictions and that, in fact, science cannot actually achieve more than that...The test of an explanatory theory, therefore, is its success at prediction, at forecasting. This view need not be limited to actual predictions of future, yet to happen events; it can accommodate theories that are able to generate results that have already been observed or, if not observed, have already occurred...it must have some reach beyond the data used to construct the theory“

More novel predictions of the TAAO

Therefore, since the TAAO has success in its predictions and hereditarian ones don’t (they don’t even make any novel predictions), it’s only rational to accept the theory that makes successful novel predictions over the one that doesn’t. The only reason one would accept the hereditarian explanations over the TAAO is due to bias and ignorance (racism), since the TAAO is a much more robust theory that actually has explanatory AND predictive power. So the issue here is quite clear—since we know the causes of black crime due to the successful novel predictions that the TAAO generates, then there are clear and actionable things we can do to try to mitigate the crime rate. This is something that hereditarian theories don’t do, most importantly because they don’t make any novel predictions. Since the TAAO makes successful risky novel predictions—predictions that, if they didn’t hold, they would then refute the theory—and since the predictions hold, then the theory is more likely to be true than not. The TAAO not only accommodates, but it makes predictions, and we can’t say the same for hereditarianism.

The issue is that so-called “race-neutral” theories of crime need to assume that racial discrimination isn’t a cause of black American offending because this would then limit it only to black Americans. Therefore race-neutral theories of crime don’t have the same predictive and explanatory power as a race-centric theory of crime—which is what the TAAO is. It’s clear that: the TAAO makes successful novel predictions, the predictions aren’t used as premises in the TAAO, the TAAO is a race-centric, country-specific theory of crime (and not a general theory of crime), racism and stereotypes don’t explain offending for non-African Americans, the theory doesn’t say that blacks lack agency, IQ doesn’t explain crime within families, and cope from hereditarians that one day we will find genes or neurohormonal influences which lead to crime in black Americans is just cope. It’s clear that the TAAO is the superior theory of crime because it does what scientific theories are supposed to do: successfully predict novel facts of the matter, something that hereditarianism just does not do which is why I’m justified in calling it a racist movement. Basically since there are unique characters of a demographic that require perspectives that are solely related to that group, then we need group-centric theories of crime due to the unique experiences of thsg group, and this is what the TAAO does.

Now that I’ve answered common criticisms of the TAAO, I have a few more successful novel predictions of the theory. In my original article I cited 3 novel predictions, how they followed from the theory, and then the references that confirmed the predictions:

(Prediction 1) Black Americans with a stronger sense of racial identity are less likely to engage in criminal behavior than black Americans with a weak sense of racial identity. How does this prediction follow from the theory? TAAO suggests that a strong racial identity can act as a protective factor against criminal involvement. Those with a stronger sense of racial identity may be less likely to engage in criminal behavior as a way to cope with racial discrimination and societal marginalization. (Burt, Simons, and Gibbons, 2013; Burt, Lei, and Simons, 2017; Gaston and Doherty, 2018; Scott and Seal, 2019)

(Prediction 2) Experiencing racial discrimination increases the likelihood of black Americans engaging in criminal actions. How does this follow from the theory? TAAO posits that racial discrimination can lead to feelings of frustration and marginalization, and to cope with these stressors, some individuals may resort to committing criminal acts as a way to exert power or control in response to their experiences of racial discrimination. (Unnever, 2014; Unnever, Cullen, and Barnes, 2016; Herda, 2016, 2018; Scott and Seal, 2019)

(Prediction 3) Black Americans who feel socially marginalized and disadvantaged are more prone to committing crime as a coping mechanism and have weakened school bonds. How does this follow from the theory? TAAO suggests that those who experience social exclusion and disadvantage may turn to crime as a way to address their negative life circumstances. and feelings of agency. (Unnever, 2014; Unnever, Cullen, and Barnes, 2016)

(Prediction 4) Black people who experience microaggreesions and perceive injustices in the criminal justice system are more likely to engage in serious and violent offending. How does this follow from the theory? Experiences of racial discrimination and marginalization can lead to negative emotions like anger and depression among black people. These negative emotions, which are then exacerbated by microaggreesions and perceptions of injustice in the criminal justice system, may increase the likelihood of engaging in serious and violent offending as a coping mechanism or means of asserting power. But, again, those with a stronger racial identity may be more resilient to the effect of discrimination (Isom, 2015).

(Prediction 5) Black Americans who perceive a lack of opportunity for socioeconomic advancement due to systemic barriers are more inclined to engage in criminal activity as a means of economic survival and social mobility. How does this follow from the theory? Perceptions of limited opportunities and systemic injustices can drive individuals to engage in criminal behaviors as a response to inequality (Vargas, 2023).

The fact that the TAAO generates these novel and successful predictions is evidence that we should accept the theory.

We also know that perceptions of criminal injustice predict offending (Bouffard and Piquero, 2013), we know that blacks are more likely than whites to perceive criminal injustice (Brunson and Weitzer, 2009) and we know that there are small differences among blacks and their perception of criminal injustice (Unnever, Gabbidon, and Higgins, 2011). So knowing this, more blacks should offend, right? Wrong. The vast majority of blacks don’t offend even though they share the same belief about the injustices of the criminal justice system. So how can we explain that? “Positive ethnic-racial socialization buffers the effect of weak school bonds on adolescent substance use and adult offending” (Gaston and Doherty, 2018). So the discrimination that black Americans have erodes their trust in social institutions like the school system, and then these weakened school bonds then increase the risk of offending.

Supporting a major tenet of TAAO and prior research on the protective ability of ethnic-racial socialization, the analyses showed that Black males who received positive ethnic-racial socialization messages in childhood develop resilience to the criminogenic effect of weak school bonds and face a lower risk for offending over the life course. (Gaston and Doherty, 2018)

One factor that is salient in the TAAO is racial subordination. We know that black people don’t commit crime because they are black, but we know that their offending is related to socio-environmental context like poverty, bad schools (while racism and stereotypes weaken school bonds blacks have, which makes them more likely to offend), broken families, and lead exposure (Butler, 2010) of which the TAAO addresses. We also know that there is no such thing as a “safe” level of lead exposure and that the relationship between lead and crime is robust and replicated across different countries and cultures. We also know that blacks were used as an experiment of sorts, where they were knowingly exposed to lead paint in subsidized homes.

This environmental racism (Washington, 2019), then, is another aspect of the racial subordination of blacks. And from 1976 to 2005, blacks were 7 times more likely than whites to commit murder. The fact of the matter is, the black-white murder gap has been large for over 100 years. And in discussing environmental racism, Unnever and Gabbidon (2011: 188) are explicit about the so-called genetic hypothesis of crime: “We want to be perfectly clear that our argument in no way is related to the thesis that there is a genetic cause to African American offending.” Therefore, this question doesn’t strike the heart of the TAAO and is just an attempt at evading the successful novel predictions the theory generates.

Conclusion

I’ve shown that the common “criticisms” of the TAAO are anything but and are easily answered. I then gave more successful predictions of the TAAO. It’s quite clear that one should accept the TAAO over hereditarian explanations. We also know that black isolation is a predictor of crime as well—even in 1996 blacks accounted for over 50 percent of murders and two-thirds of robberies (Shihadeh and Flynn, 1996). In 2020, blacks were six times more likely to be arrested for murder than whites. We also know that the belief by blacks in the violent stereotype predicts their offending and their adherence to the stereotype predicts crime and self control (Unnever, 2014). Therefore, a kind of stereotype threat arises here and has effects during police encounters like wkth height (Hester and Gray, 2018)(Najdowski, Bottoms, and Goff, 2015; Strine, 2018; Najdowski, 2012, 2023) , with one argument that race stereotypes track ecology, not race, (Williams, 2023) (just like for IQ; Steele and Aronson, 1995; Thames et al, 2014). We know that stereotype threats weaken school bonds and that weakened school bonds are related to offending, therefore we can infer that stereotype threats lead to an increase in crime (Unnever and Gabbidon, 2011).

Unnever and Gabbidon were quite clear and explicit in their argument and the hypotheses and predictions they made based on their theory. So when tested, if they were found not to hold then the theory would be falsified. But the theories held under empirical examination. Unnever and Gabbidon (2011: 98) were explicit in their theory and what it meant:

Put simply, we hypothesize that the probability of African American offending increases as blacks become more aware of toxic stereotypes, encounter stereotype threats, and are discriminated against because of their race. Our theory additionally posits that these forms of racism impact offending because they undermine the ability of African Americans to develop strong ties with conventional institutions. The extant literature indicates that stereotype threats and personal experiences of racial discrimination negatively impact the strength of the bonds (attachment, involvement, commitment) that black students have with their schools (Smalls, White, Chavous, and Sellers, 2007; Thomas, Caldwell, Faison, and Jackson, 2009). And, the research is clear; weak social bonds increase the probability of black offending (Carswell, 2007).

The worldview shared by black Americans is a consequence of the experience they and their ancestors had in America. This then explains their offending patterns, and why they commit more crime than whites. The socio-historical context that the TAAO looks to explain black crime is robust. Since the TAAO is successful in what it sets out to do, then, I wouldn’t doubt that there should be other race-centric theories of crime that try to explain and predict offending in those populations. The empirical successes of the TAAO’s predictions attest to the fact that other theories of crime for other races would be fruitful in predicting and explaining crime in those groups.

Hereditarians dream of having a theory that enjoys the empirical support that the TAAO has. The fact that the TAAO makes successful novel predictions and hereditarianism doesn’t is reason enough to reject hereditarian explanations and accept the TAAO. Accepting a theory that makes novel predictions is rational since it speaks to the theory’s predictive power. So by generating predictions that were previously unknown or untested and them confirming them through empirical evidence, the theory therefore shows its ability to predict and anticipate real-world phenomena. This then strengthens confidence in the theory’s underlying principles which provides a framework for understanding complex phenomena. Further, the ability of a theory to make such predictions suggests that the theory is robust and adaptable, meaning that it’s capable of accommodating new data while refining our understanding over time.

Hereditarians would love nothing more than to reduce black criminality to their genes or hormones, but reality tells a different story, and it’s one where the TAAO exists and makes successful novel predictions.

Race, Racism, Stereotypes, and Crime: An Argument for Why Racism is Morally Wrong

2300 words

Introduction

(1) Crime is bad. (2) Racism causes crime. (C) Thus, racism is morally wrong. (1) is self-evident based on people not wanting to be harmed. (2) is known upon empirical examination, like the TAAO and it’s successful novel predictions. (C) then logically follows. In this article, I will give the argument in formal notation and show its validity while defending the premises and then show how the conclusion follows from the premises. I will then discuss two possible counter arguments and then show how they would fail. I will show that you can derive normative conclusions from ethical and factual statements (which then bypasses the naturalistic fallacy), and then I will give the general argument I am giving here. I will discuss other reasons why racism is bad (since it leads to negative physiological and mental health outcomes), and then conclude that the argument is valid and sound and I will discuss how stereotypes and self-fulfilling prophecies also contribute to black crime.

Defending the argument

This argument is obviously valid and I will show how.

B stands for “crime is bad”, C stands for “racism causes crime”, D stands for racism is objectively incorrect, so from B and C we derive D (if C causes B and B is bad, then D is morally wrong). So the argument is “(B ^ C) -> D”. B and C lead to D, proving validity.

Saying “crime is bad” is an ethical judgement. The term “bad” is used as a moral or ethical judgment. “Bad” implies a negative ethical assessment which suggests that engaging in criminal actions is morally undesirable or ethically wrong. The premise asserts a moral viewpoint, claiming that actions that cause harm—including crime—are inherently bad. It implies a normative stance which implies that criminal behavior is wrong or morally undesirable. So it aligns with the idea that causing harm, violating laws or infringing upon others is morally undesirable.

When it comes to the premise “racism causes crime”, this needs to be centered on the theory of African American offending (TAAO). It’s been established that blacks experiencing racism is causal for crime. So the premise implies that racism is a factor in or contributes to criminal behavior amongst blacks who experience racism. Discriminatory practices based on race (racism) could lead to social inequalities, marginalization and frustration which would then contribute to criminal behavior among the affected person. This could also highlight systemic issues where racist policies or structures create an environment conducive to crime. And on the individual level, experiences of racism could influence certain individuals to engage in criminal activity as a response or coping mechanism (Unnever, 2014; Unnever, Cullen, and Barnes, 2016). Perceived racial discrimination “indirectly predicted arrest, and directly predicted both illegal behavior and jail” (Gibbons et al, 2021). Racists propose that what causes the gap is a slew of psychological traits, genetic factors, and physiological variables, but even in the 1960s, criminologists and geneticists rejected the genetic hypothesis of crime (Wolfgang,1964). However we do know there is a protective effect when parents prepare their children for bias (Burt, Simons, and Gibbons, 2013). Even the role of institutions exacerbates the issue (Hetey and Eberhardt, 2014). And in my article on the Unnever-Gabbidon theory of African American offending, I wrote about one of the predictions that follows from the theory which was borne out when it was tested.

So it’s quite obvious that the premise “racism causes crime” has empirical support.

So if B and C are true then D follows. The logical connection between B and C leads to the conclusion that “racism is morally wrong”, expressed by (B ^ C) -> D. Now I can express this argument using modus ponens.

(1) If (B ^ C) then D. (Expressed as (B ^ C) -> D).

(2) (B ^ C) is true.

(3) Thus, D is true.

When it comes to the argument as a whole it can be generalized to harm is bad and racism causes harm so racism is bad.

Furthermore, I can generalize the argument further and state that not only that crime is bad, but that racism leads to psychological harm and harm is bad, so racism is morally wrong. We know that racism can lead to “weathering” (Geronimus et al, 2006, 2011; Simons, 2021) and increased allostatic load (Barr 2014: 71-72). So racism leads to a slew of unwanted physiological issues (of which microaggressions are a species of; Williams, 2021).

Racism leads to negative physiological and mental health outcomes (P), and negative physiological and mental health outcomes are undesirable (Q), so racism is morally objectionable (R). So the factual statement (P) establishes a link between negative health outcomes, providing evidence that racism leads to these negative health outcomes. The ethical statement (Q) asserts that negative health outcomes are morally undesirable which aligns with a common ethical principle that causing harm is morally objectionable. Then the logical connection (Q ^ P) combines the factual observation of harm caused by racism with the ethical judgment that harm is morally undesirable. Then the normative conclusion (R) follows, which asserts that racial is morally objectionable since it leads to negative health outcomes. So this argument is (Q ^ P) -> R.

Racism can lead to stereotyping of certain groups as more prone to criminal behavior, and this stereotype can be internalized and perpetuated which would then contribute to biased law enforcement and along with it unjust profiling. It can also lead to systemic inequalities like in education, employment and housing which are then linked to higher crime rates (in this instance, racism and stereotyping causes the black-white crime gap, as predicted by Unnever and Gabbidon, 2011 and then verified by numerous authors). Further, as I’ve shown, racism can negatively affect mental health leading to stress, anxiety and trauma and people facing these challenges would be more vulnerable to engage in criminal acts.

Stereotypes and self-fulfilling prophecies

In his book Concepts and Theories of Human Development, Lerner (2018: 298) discusses how stereotyping and self-fulfilling prophecies would arise from said stereotyping. He says that people, based on their skin color, are placed into an unfavorable category. Then negative behaviors were attributed to the group. Then these behaviors were associated with different experience in comparison to other skin color groups. These different behaviors then delimit the range of possible behaviors that could develop. So the group was forced into a limited number of possible behaviors, the same behaviors they were stereotyped to have. So the group finally develops the behavior due to being “channeled” (to use Lerner’s word) which is then “the end result of the physically cued social stereotype was a self-fulfilling prophecy” (Lerner, 2018: 298).

From the analysis of the example I provided and, as well, from empirical literature in support of it (e.g., Spencer, 2006; Spencer et al., 2015), a strong argument can be made that the people of color in the United States have perhaps experienced the most unfortunate effects of this most indirect type of hereditary contribution to behavior–social stereotypes. Thus, it may be that African Americans for many years have been involved in an educational and intellectual self-fulfilling prophecy in the United States. (Lerner, 2018: 299)

This is an argument about how social stereotypes can spur behavioral development, and it has empirical support. Lerner’s claim that perception influences behavior is backed by Spencer, Swanson and Harpalani’s (2015) article on the development of the self and Spencer, Dupree, and Hartman’s (1997) phenomenological variant of ecological systems theory (PVEST). (Also see Cunningham et al, 2023). Spencer, Swanson and Harpalani (2015: 764) write:

Whether it is with images of the super-athlete, criminal, gangster, or hypersexed male, it seems that most of society’s views of African Americans are defined by these stereotypes. The Black male has, in one way or another, captured the imagination of the media to such a wide extent that media representations create his image far more than reality does. Most of the images of the Black male denote physical prowess or aggression and downplay other characteristics. For example, stereotypes of Black athletic prowess can be used to promote the notion that Blacks are unintelligent (Harpalani, 2005). These societal stereotypes, in conjunction with numerous social, political, and economic forces, interact to place African American males at extreme risk for adverse outcomes and behaviors.

A -> B—So stereotypes can lead to self-fulfilling prophecies (if there are stereotypes, then they can result in self-fulfilling prophecies). B -> C—Self-fulfilling prophecies can increase the chance of crime for blacks (if there are self-fulfilling prophecies, then they can increase the chance of crime for blacks. So A -> C—Stereotypes can increase the chance of crime for blacks (if there are stereotypes, then they can increase the chance of crime for blacks). Going back to the empirical studies on the TAAO, we know that racism and stereotypes cause the black-white crime gap (Unnever, 2014; Unnever, Cullen, and Barnes, 2016; Herda, 2016, 2018; Scott and Seal, 2019), and so the argument by Spencer et al and Lerner is yet more evidence that racism and stereotypes lead to self-fulfilling prophecies which then cause black crime. Behavior can quite clearly be shaped by stereotypes and self-fulfilling prophecies.

Responses to possible counters

I think there are 3 ways that one could try to refute the argument—(1) Argue that B is false, (2) argue that C is false, or (3) argue that the argument commits the is-ought fallacy.

(1) Counter premise: B’: “Not all crimes are morally bad, some may be morally justifiable or necessary in certain contexts. So if not all crimes are morally bad, then the conclusion that racism is morally wrong based on the premises (B ^ C) isn’t universally valid.”

Premise B reflects a broad ethical judgment which is based on social norms that generally view actions that cause harm morally undesirable. My argument is based on consequences—that racism causes crime. The legal systems of numerous societies categorize certain actions as crimes since they are deemed morally reprehensible and harmful to individuals and communities. Thus, there is a broad moral stance against actions that cause harm which is reflected in the societal normative stance against actions which cause harm.

(2) Counter premise: C’: “Racism does not necessarily cause crime. Since racism does not necessarily cause crime, then the conclusion that racism is objectively wrong isn’t valid.”

Premise C states that racism causes crime. When I say that, it doesn’t mean that every instance of racism leads to an instance of crime. Numerous social factors contribute to criminal actions, but there is a relationship between racial discrimination (racism) and crime:

Experiencing racial discrimination increases the likelihood of black Americans engaging in criminal actions. How does this follow from the theory? TAAO posits that racial discrimination can lead to feelings of frustration and marginalization, and to cope with these stressors, some individuals may resort to commuting criminal acts as a way to exert power or control in response to their experiences of racial discrimination. (Unnever, 2014; Unnever, Cullen, and Barnes, 2016; Herda, 2016, 2018; Scott and Seal, 2019)

(3) “The argument commits the naturalistic fallacy by inferring an “ought” from an “is.” It appears to derive a normative conclusion from factual and ethical statements. So the transition from descriptive premises to moral judgments lacks a clear ethical justification which violates the naturalistic fallacy.” So this possible counter contends that normative statement B and the ethical statement C isn’t enough to justify the normative conclusion D. Therefore it questions whether the argument has good justification for an ethical transition to the conclusion D.”

I can simply show this. Observe X causing Y (C). Y is morally undesirable (B). Y is morally undesirable and X causes Y (B ^ C). So X is morally objectionable (D). So C begins with an empirical finding. B then is the ethical premise. The logical connection is then established with B ^ C (which can be reduced to “Harm is morally objectionable and racism causes harm”). This then allows me to infer the normative conclusion—D—allowing me to bypass the charge of committing the naturalistic fallacy. Thus, the ethical principle that harm is morally undesirable and that racism causes harm allows me to derive the conclusion that racism is objectively wrong. So factual statements can be combined with ethical statements to derive ethical conclusions, bypassing the naturalistic fallacy.

Conclusion

This discussion centered on my argument (B ^ C) -> D. The argument was:

(P1) Crime is bad (whatever causes harm is bad). (B)

(P2) Racism causes crime. (C)

(C) Racism is morally wrong. (D)

I defended the truth of both premises, and then I answered two possible objections, both rejecting B and C. I then defended my argument against the charge of it committing the naturalistic fallacy by stating that ethical statements can be combined with factual statements to derive normative conclusions. Addressing possible counters (C’ and B’), I argued that there is evidence that racism leads to crime (and other negative health outcomes, generalized as “harm”) in black Americans, and that harm is generally seen as bad, so it then follows that C’ and B’ fail. Spencer’s and Lerner’s arguments, furthermore, show how stereotypes can spur behavioral development, meaning that social stereotypes increase the chance of adverse behavior—meaning crime. It is quite obvious that the TAAO has strong empirical support, and so since crime is bad and racism causes crime then racism is morally wrong. So to decrease the rate of black crime we—as a society—need to change our negative attitudes toward certain groups of people.

Thus, my argument builds a logical connection between harm being bad, racism causing harm and moral undesirability. In addressing potential objections and clarifying the ethical framework I ren, So the general argument is: Harm is bad, racism causes harm, so racism is morally wrong.

The Theory of African American Offending versus Hereditarian Explanations of Crime: Exploring the Roots of the Black-White Crime Disparity

3450 words

Why do blacks commit more crime? Biological theories (racial differences in testosterone and testosterone-aggression, AR gene, MAOA) are bunk. So how can we explain it? The Unnever-Gabbidon theory of African American offending (TAAO) (Unnever and Gabbidon, 2011)—where blacks’ experience of racial discrimination and stereotypes increases criminal offenses—has substantial empirical support. To understand black crime, we need to understand the unique black American experience. The theory not only explains African American criminal offending, it also makes predictions which were borne out in independent, empirical research. I will compare the TAAO with hereditarian claims of why blacks commit more crime (higher testosterone and higher aggression due to testosterone, the AR gene and MAOA). I will show that hereditarian theories make no novel predictions and that the TAAO does make novel predictions. Then I will discuss recent research which shows that the predictions that Unnever and Gabbidon have made were verified. Then I will discuss research which has borne out the predictions made by Unnever and Gabbidon’s TAAO. I will conclude by offering suggestions on how to combat black crime.

The folly of hereditarianism in explaining black American offending

Hereditarians have three main explanations of black crime: (1) higher levels of testosterone and high levels of testosterone leading to aggressive behavior which leads to crime; (2) low activity MAOA—also known in the popular press as “the warrior gene”—could be more prevalent in some populations which would then lead to more aggressive, impulsive behavior; and (3) the AR gene and AR-CAG repeats with lower CAG repeats being associated with higher rates of criminal activity.

When it comes to (1), the evidence is mixed on which race has higher levels of testosterone (due to low-quality studies that hereditarians cite for their claim). In fact, two recent studies showed that non-Hispanic blacks didn’t have higher levels of testosterone than other races (Rohrmann et al, 2007; Lopez et al, 2013). Contrast this with the classical hereditarian response that blacks indeed do have higher rates of testosterone than whites (Rushton, 1995)—using Ross et al (1986) to make the claim. (See here for my response on why Ross et al is not evidence for the hereditarian position.) Although Nyante et al (2012) showed a small increase in testosterone in blacks compared to whites and Mexican Americans using longitudinal data, the body of evidence shows that there is no to small differences in testosterone between blacks and whites (Richard et al, 2014). So despite claims that “African-American men have repeatedly demonstrated serum total and free testosterone levels that are significantly higher than all other ethnic groups” (Alvarado, 2013: 125), claims like this are derived from flawed studies, and newer more representative analyses show that there is a small difference in testosterone between blacks and whites to no difference.

Nevertheless, even if blacks have higher levels of testosterone than other races, then this would still not explain racial differences in crime, since heightened aggression explains T increases, high T doesn’t explain heightened aggression. HBDers seem to have cause and effect backwards for this relationship. Injecting individuals with supraphysiological doses of testosterone as high as 200 and 600 mg per week does not cause heightened anger or aggression (Tricker et al, 1996; O’Connor et, 2002). If the hereditarian hypothesis on the relationship between testosterone and aggression were true, then we would see the opposite finding from what Tricker et al and O’Connor et al found. Thus this discussion shows that hereditarians are wrong about racial differences in testosterone and that they are wrong about causality when it comes to the T-aggression relationship. (The actual relationship is aggression causing increases in testosterone.) So this argument shows that the hereditarian simplification on the T-aggression relationship is false. (But see Pope, Kouri and Hudson, 2000 where they show that a 600 mg dose of testosterone caused increased manic symptoms in some men, although in most men there was little to no change; there were 8 “responders” and 42 “non-responders.”)

When it comes to (2), MAOA is said to explain why those who carry low frequency version of the gene have higher rates of aggression and violent behavior (Sohrabi, 2015; McSwiggin, 2017). Sohrabi shows that while the low frequency version of MAOA is related to higher rates of aggression and violent behavior, it is mediated by environmental effects. But MAOA, to quote Heine (2017), can be seen as the “Everything but the kitchen sink gene“, since MAOA is correlated with so many different things. But at the and of the day, we can’t blame “warrior genes” for violent, criminal behavior. Thus, the relationship isn’t so simple, so this doesn’t work for hereditarians either.

Lastly when it comes to (3), due to the failure of (1), hereditarians tried looking to the AR gene. Researchers tried to relate CAG repeat length with criminal behaviors. For instance, Geniole et al (2019) tried to argue that “Testosterone thus appears to promote human aggression through an AR-related mechanism.” Ah, the last gasps to explain crime through testosterone. But there is no relationship between CAG repeats, adolescent risk-taking, depression, dominance or self-esteem (Vermeer, 2010) and the number of CAG repeats in men and women (Valenzuela et al, 2022). So this, too, fails. (Also take look at the just-so story on why African slave descendants are more sensitive to androgens; Aiken, 2011.)

Now that I have shown that the three main hereditarian explanations for higher black crime are false, now I will show why blacks have higher rates of criminal offending than other races, and the answer isn’t to be found in biology, but sociology and criminology.

The Unnever-Gabbidon theory of African American criminal offending and novel predictions

In 2011, criminologists Unnever and Gabbidon published their book A Theory of African American Offending: Race, Racism, and Crime. In the book, they explain why they formulated the theory and why it doesn’t have any explanatory or predictive power for other races. That’s because it centers on the lived experiences of black Americans. In fact, the TAAO “incorporates the finding that African Americans are more likely to offend if they associate with delinquent peers but we argue that their inadequate reinforcement for engaging in conventional behaviors is related to their racial subordination” (Unnever and Gabbidon, 2011: 34). The TAAO focuses on the criminogenic effects of racism.

Our work builds upon the fundamental assumption made by Afrocentists that an understanding of black offending can only be attained if their behavior is situated within the lived experiences of being African American in a conflicted, racially stratified society. We assert that any criminological theory that aims to explain black offending must place the black experience and their unique worldview at the core of its foundation. Our theory places the history and lived experiences of African American people at its center. We also fully embrace the Afrocentric assumption that African American offending is related to racial subordination. Thus, our work does not attempt to create a “general” theory of crime that applies to every American; instead, our theory explains how the unique experiences and worldview of blacks in America are related to their offending. In short, our theory draws on the strengths of both Afrocentricity and the Eurocentric canon. (Unnever and Gabbidon, 2011: 37)

Two kinds of racial injustices highlighted by the theory—racial discrimination and pejorative stereotyping—have empirical support. Blacks are more likely to express anger, exhibit low self-control and become depressed if they believe the racist stereotype that they’re violent. It’s also been studied whether or not a sense of racial injustice is related to offending when controlling for low self control (see below).

The core predictions of the TAAO and how they follow from it with references for empirical tests are as follows:

(Prediction 1) Black Americans with a stronger sense of racial identity are less likely to engage in criminal behavior than black Americans with a weak sense of racial identity. How does this prediction follow from the theory? TAAO suggests that a strong racial identity can act as a protective factor against criminal involvement. Those with a stronger sense of racial identity may be less likely to engage in criminal behavior as a way to cope with racial discrimination and societal marginalization. (Burt, Simons, and Gibbons, 2013; Burt, Lei, and Simons, 2017; Gaston and Doherty, 2018; Scott and Seal, 2019)

(Prediction 2) Experiencing racial discrimination increases the likelihood of black Americans engaging in criminal actions. How does this follow from the theory? TAAO posits that racial discrimination can lead to feelings of frustration and marginalization, and to cope with these stressors, some individuals may resort to committing criminal acts as a way to exert power or control in response to their experiences of racial discrimination. (Unnever, 2014; Unnever, Cullen, and Barnes, 2016; Herda, 2016, 2018; Scott and Seal, 2019)

(Prediction 3) Black Americans who feel socially marginalized and disadvantaged are more prone to committing crime as a coping mechanism and have weakened school bonds. How does this follow from the theory? TAAO suggests that those who experience social exclusion and disadvantage may turn to crime as a way to address their negative life circumstances. and feelings of agency. (Unnever, 2014; Unnever, Cullen, and Barnes, 2016)

The data show that there is a racialized worldview shared by blacks, and that a majority of blacks believe that their fate rests on what generally happens to black people in America. Around 38 percent of blacks report being discriminated against and most blacks are aware of the stereotype of them as violent. (Though a new Pew report states that around 8 in 10—about 80 percent—of blacks have experienced racial discrimination.) Racial discrimination and the belief in the racist stereotype that blacks are more violent are significant predictors of black arrests. It’s been shown that the more blacks are discriminated against and the more they believe that blacks are violent, the more likely they are to be arrested. Unnever and Gabbidon also theorized that the aforementioned isn’t just related to criminal offending but also to substance and alcohol abuse. Unnever and Gabbidon also hypothesized that racial injustices are related to crime since they increase the likelihood of experiencing negative emotions like anger and depression (Simons et al, 2002). It’s been experimentally demonstrated that blacks who perceive racial discrimination and who believe the racist stereotype that blacks are more violent express less self-control. The negative emotions from racial discrimination predict the likelihood of committing crime and similar behavior. It’s also been shown that blacks who have less self-control, who are angrier and are depressed have a higher liklihood of offending. Further, while controlling for self-control, anger and depression and other variables, racial discrimination predicts arrests and substance and alcohol abuse. Lastly the experience of being black in a racialized society predicts offending, even after controlling for other measures. Thus, it is ruled out that the reason why blacks are arrested more and perceive more racial injustice is due to low self-control. (See Unnever, 2014 for the citations and arguments for these predictions.) The TAAO also has more empirical support than racialized general strain theory (RGST) (Isom, 2015).

So the predictions of the theory are: Racial discrimination as a contributing factor; a strong racial identity could be a protective factor while a weak racial identity would be associated with a higher likelihood of engaging in criminal activity; blacks who feel socially marginalized would turn to crime as a response to their disadvantaged social position; poverty, education and neighborhood conditions play a significant role in black American offending rates, and that these factors interact with racial identity and discrimination which then influence criminal behavior; and lastly it predicts that the criminal justice system’s response to black American offenders could be influenced by their racial identity and social perceptions which could then potentially lead to disparities in treatment compared to other racial groups.

Ultimately, the unique experiences of black Americans explain why they commit more crime. Thus, given the unique experiences of black Americans, there needs to be a race-centric theory of crime for black Americans, and this is exactly what the TAAO is. The predictions that Unnever and Gabbidon (2011) made from the TAAO have independent empirical support. This is way more than the hereditarian explanations can say on why blacks commit more crime.

One way, which follows from the theory, to insulate black youth from discrimination and prejudice is racial socialization, where racial socialization is “thoughts, ideas, beliefs, and attitudes regarding race and racism are communicated across generations (Burt, Lei, & Simons, 2017; Hughes, Smith, et al., 2006; Lesane-Brown, 2006) (Said and Feldmeyer, 2022).

But also related to the racial socialization hypothesis is the question “Why don’t more blacks offend?” Gaston and Doherty (2018) set out to answer this question. Gaston and Doherty (2018) found that positive racial socialization buffered the effects of weak school bonds on adolescent substance abuse and criminal offending for males but not females. This is yet again another prediction from the theory that has come to pass—the fact that weak school bonds increase criminal offending.

Doherty and Gaston (2018) argue that black Americans face racial discrimination that whites in general just do not face:

Empirical studies have pointed to potential explanations of racial disparities in violent crimes, often citing that such disparities reflect Black Americans’ disproportionate exposure to criminogenic risk factors. For example, Black Americans uniquely experience racial discrimination—a robust correlate of offending—that White Americans generally do not experience (Burt, Simons, & Gibbons, 2012; Caldwell, Kohn-Wood, Schmeelk-Cone, Chavous, & Zimmerman, 2004; Simons, Chen, Stewart, & Brody, 2003; Unnever, Cullen, Mathers, McClure, & Allison, 2009). Furthermore, Black Americans are more likely to face factors conducive to crime such as experiencing poor economic conditions and living in neighborhoods characterized by concentrated disadvantage.

They conclude that:

The support we found for ethnic-racial socialization as a crime-reducing factor has important implications for broader criminological theorizing and practice. Our findings show the value of race-specific theories that are grounded in the unique experiences of that group and focus on their unique risk and protective factors. African Americans have unique pathways to offending with racial discrimination being a salient source of offending. While it is beyond the scope of this study to determine whether TAAO predicts African American offending better than general theories of crime, the general support for the ethnic-racial socialization hypothesis suggests the value of theories that account for race-specific correlates of Black offending and resilience.

…

TAAO draws from the developmental psychology literature and contends, however, that positive ethnic-racial socialization offers resilience to the criminogenic effect of weak school bonds and is the main reason more Black Americans do not offend (Unnever & Gabbidon, 2011, p. 113, 145).

Thus, combined with the fact that blacks face racial discrimination that whites in general just do not face, and combined with the fact that racial discrimination has been shown to increase criminal offending, it follows that racial discrimination can lead to criminal offending, and therefore, to decrease criminal offending we need to decrease racial discrimination. Since racism is due to low education and borne of ignorance, then it follows that education can decrease racial attitudes and, along with it, decrease crime (Hughes et al, 2007; Kuppens et al, 2014; Donovan, 2019, 2022).

Even partial tests of the TAAO have shown that racial discrimination related to offending and I would say that it is pretty well established that positive ethnic-racial socialization acts as a protective factor for blacks—this also explains why more blacks don’t offend (see Gaston and Doherty, 2018). It is also know that bad (ineffective) parenting also increases the risk for lower self-control (Unnever, Cullen, and Agnew, 2006). Black Americans share a racialized worldview and they view the US as racist, due to their personal lived experiences with racism (Unnever, 2014).

The TAAO and situationism

Looking at what the TAAO is and the predictions it makes, we can see how the TAAO is a situationist theory. Situationism is a psychological-philosophical theory which emphasizes the influence of the situation and its effects on human behavior. It posits that people’s actions and decisions are primarily shaped by the situational context that they find themselves in. It highlights the role of the situation in explaining behavior, suggests that people may act differently based on the context they find themselves in, situational cues which are present in the immediate context of the environment can trigger specific behavioral responses, suggests that understanding the situation one finds themselves in is important in explaining why people act the way they do, and asserts that behavior is more context-dependent and unpredictable and could vary across different situations. Although it seems that situationism conflicts with action theory, it doesn’t. Action theory explains how people form intentions and make decisions within specific situations, basically addressing the how and why. Conversely, situationism actually compliments action theory, since it addresses the where and when of behavior from an external, environmental perspective.

So the TAAO suggests that experiencing racial discrimination can contribute to criminal involvement as a response to social marginalization. So situationism can provide a framework for exploring how specific instances of environmental stressors, discrimination, or situational factors can trigger criminal behavior in context. So while TAAO focuses on historical and structural factors which lead to why blacks commit more crime, adding in situationism could show how the situational context interacts with historical and structural factors to explain black American criminal behavior.

Thus, combining situationism and the TAAO can lead to novel predictions like: predictions of how black Americans when faced with specific discriminatory situations, may be more or less likely to engage in criminal behavior based on their perception of the situation; predictions about the influence of immediate peer dynamics in moderating the relationship between structural factors like discrimination and criminal behavior in the black American community; and predictions about how variations in criminal responses to different types of situational cues—like encounters with law enforcement, experiences of discrimination, and economic stress—within the broader context of the TAAO’s historical-structural framework.

Why we should accept the TAAO over hereditarian explanations of crime

Overall, I’ve explained why hereditarian explanations of crime fail. They fail because when looking at the recent literature, the claims they make just do not hold up. Most importantly, as I’ve shown, hereditarian explanations lack empirical support, and the logic they try to use in defense of them is flawed.

We should accept the TAAO over hereditarianism because there is empirical validity, in that the TAAO is grounded in empirical research and it’s predictions and hypotheses have been subject to empirical tests and they have been found to hold. The TAAO also recognizes that crime is a complex phenomena influenced by factors like historical and contemporary discrimination, socioeconomic conditions, and the overall situational context. It also addresses the broader societal issues related to disparities in crime, which makes it more relevant for policy development and social interventions, acknowledging that to address these disparities, we must address the contemporary and historical factors which lead to crime. The TAAO also doesn’t stigmatize and stereotype, while it does emphasize the situational and contextual factors which lead to criminal activity. On the other hand, hereditarian theories can lead to stereotypes and discrimination, and since hereditarian explanations are false, we should also reject them (as I’ve explained above). Lastly, the TAAO also has the power to generate specific, testable predictions which have clear empirical support. Thus, to claim that hereditarian explanations are true while disregarding the empirical power of the TAAO is irrational, since hereditarian explanations don’t generate novel predictions while the TAAO does.

Conclusion

I have contrasted the TAAO with hereditarian explanations of crime. I showed that the three main hereditarian explanations—racial differences in testosterone and testosterone caused aggression, the AR gene, and MAOA—all fail. I have also shown that the TAAO is grounded in empirical research, and that it generates specific, testable predictions on how we can address racial differences in crime. On fhe other hand, hereditarian explanations lack empirical support, specificity, and causality, which makes it ill-suited for generating testable predictions and informing effective policies. The TAAO’s complexity, empirical support, and potential for addressing real-world issues makes it a more comprehensive framework for understanding and attempting to ameliorate racial crime disparities, in contrast to the genetic determinism from hereditarianism. In fact, I was unable to find any hereditarian response to the TAAO, so that should be telling on its own.

Overall, I have shown that the TAAO’s predictions that Unnever and Gabbidon have generated enjoy empirical support, and I have shown that hereditarian explanations fail, so we should reject hereditarian explanations and accept the TAAO, due to the considerations above. I have also shown that the TAAO makes actionable policy recommendations, and therefore, to decrease criminal offending, we thusly need to educate more, since racism is borne of ignorance and education can decrease racial bias.

Nutrition and Antisocial Behavior

2150 words

What is the relationship between nutrition and antisocial behavior? Does not consuming adequate amounts of vitamins and minerals lead to an increased risk for antisocial behavior? If it does, then lower class people will have commit crimes at a higher rate, and part of the problem may indeed be dietary. Though, what kind of data is there that lends credence to the idea? It is well-known that malnutrition leads to antisocial behavior, but what kind of effect does it have on the populace as a whole?

About 85 percent of Americans lack essential vitamins and minerals. Though, when most people think of the word ‘malnutrition’ and the imagery it brings along with it, they assume that someone in a third-world country is being talked about, say a rail-thin kid somewhere in Africa who is extremely malnourished due to lack of kcal and vitamins and minerals. However, just because one lives in a first-world country and has access to kcal to where they’re “not hungry” doesn’t mean that vitamin and mineral deficiencies do not exist in these countries. This is known as “hidden hunger” when people can get enough kcal for their daily energy needs but what they are eating is lower-quality food, and thus, they become vitamin and nutrient deficient. What kind of effects does this have?

Infants are most at risk, more than half of American babies are at-risk for malnutrition; malnutrition in the postnatal years can lead to antisocial behavior and a lower ‘IQ’ (Galler and Ramsey, 1989; Liu et al, 2003; Galler et al, 2011, 2012a, 2012b; Gesch, 2013; Kuratko et al, 2013; Raine et al, 2015; Thompson et al, 2017). Clearly, not getting pertinent vitamins and minerals at critical times of development for infants leads to antisocial behavior in the future. These cases, though, can be prevented with a good diet. But the preventative measures that can prevent some of this behavior has been demonized for the past 50 or so years.

Poor nutrition leads to the development of childhood behavior problems. As seen in rat studies, for example, lack of dietary protein leads to aggressive behavior while rats who are protein-deficient in the womb show altered locomotor activity. The same is also seen with vitamins and minerals; monkeys and rats who were fed a diet low in tryptophan were reported to be more aggressive whereas those that were fed high amounts of tryptophan were calmer. Since tryptophan is one of the building blocks of serotonin and serotonin regulates mood, we can logically state that diets low in tryptophan may lead to higher levels of aggressive behavior. The role of omega 3 fatty acids are mixed, with omega 3 supplementation showing a difference for girls, but not boys (see Itomura et al, 2005). So, animal and human correlational studies and human intervention studies lend credence to the hypothesis that malnutrition in the womb and after birth leads to antisocial behavior (Liu and Raine, 2004).

We also have data from one randomized, placebo-controlled trial showing the effect of diet and nutrition on antisocial behavior (Gesch et al, 2002). They state that since there is evidence that offenders’ diets are lacking in pertinent vitamins and minerals, they should test whether or not the introduction of physiologically adequate vitamins, minerals and essential fatty acids (EFAs) would have an effect on the behavior of the inmates. They undertook an experimental, double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized trial on 231 adult prisoners and then compared their write-ups before and after nutritional intervention. The vitamin/mineral supplement contained 44 mg of DHA (omega 3 fatty acid docosahexaenoic acid; plays a key role in enhancing brain structure and function, stimulating neurite outgrowth), 80 mg of EPA (eicosapentaenoic acid; n3), and 1.26 g of ALA (alpha-linolenic acid), 1260mg of LA (linolic acid), and 160mg of GLA (gamma-Linolenic acid, n6) and a vegetable oil placebo. (Also see Hibbeln and Gow, 2015 for more information on n3 and nutrient deficits in childhood behavior disorders and neurodevelopment.)

Raine (2014: 218-219) writes:

We can also link micronutrients to specific brain structures involved in violence. The amygdala and hippocampus, which are impaired in offenders, are packed with zinc-containing neurons. Zinc deficiency in humans during pregnancy can in turn impair DNA, RNA, and protein synthesis during brain development—the building blocks of brain chemistry—and may result in very early brain abnormalities. Zinc also plays a role in building up fatty acids, which, as we have seen, are crucial for brain structure and function.

Gesch et al (2002) found pretty interesting results: those who were given the capsules with vitamins, minerals, and EFAs had 26.3 percent fewer offenses than those who got the placebo. Further, when compared with the baseline, when taking the supplement for two weeks, there was an average 35.1 percent reduction in offenses compared to the placebo group who showed little change. Gesch et al (2002) conclude:

Antisocial behaviour in prisons, including violence, are reduced by prisons, are reduced by vitamins, minerals and essential fatty acids with similar implications for those eating poor diets in the community.

Of course one could argue that these results would not transfer over to the general population, but to a critique like this, the observed effect of behavior is physiological; so by supplementing the prisoners’ diets giving them pertinent vitamins, minerals and EFAs, violence and antisocial behavior decreased, which shows some level of causation between nutrition/nutrient/fatty acid deprivation and antisocial behavior and violent activity.

Gesch et al (2002) found that some prisoners did not know how to construct a healthy diet nor did they know what vitamins were. So, naturally, since some prisoners didn’t know how to construct diets with an adequate amount of EFAs, vitamins and minerals, they were malnourished, though they consumed an adequate amount of calories. The intervention showed that EFA, vitamin and mineral deficiency has a causal effect on decreasing antisocial and violent behavior in those deficient. So giving them physiological doses lowered antisocial behavior, and since it was an RCT, social and ethnic factors on behavior were avoided.

Of course (and this shouldn’t need to be said), I am not making the claim that differences in nutrition explain all variance in antisocial and violent behavior. The fact of the matter is, this is causal evidence that lack of vitamin, mineral and EFA consumption has some causal effect on antisocial behavior and violent tendencies.

Schoenthaler et al (1996) also showed how correcting low values of vitamins and minerals in those deficient led to a reduction in violence among juvenile delinquents. Though it has a small n, the results are promising. (Also see Zaalberg et al, 2010.) These simple studies show how easy it is to lower antisocial and violent behavior: those deficient in nutrients just need to take some vitamins and eat higher-quality food and there should be a reduction in antisocial and violent behavior.

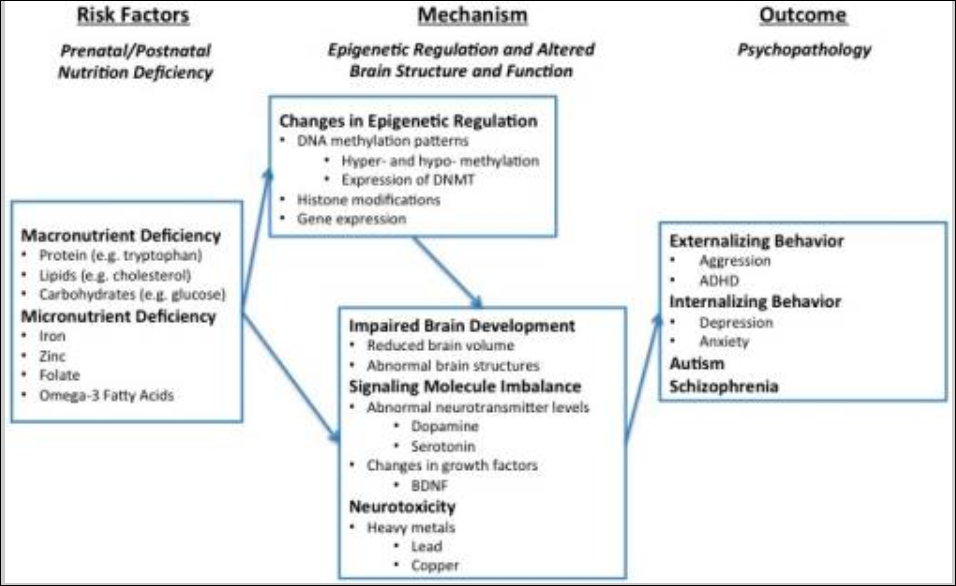

Liu, Zhao, and Reyes (2015) propose “a conceptual framework whereby epigenetic modifications (e.g., DNA methylation) mediate the link between micro- and macro-nutrient deficiency early in life and brain dysfunction (e.g., structural aberration, neurotransmitter perturbation), which has been linked to development of behavior problems later on in life.” Their model is as follows: macro- and micro-nutrient deficiencies are risk-factors for psychopathologies since they can lead to changes in the epigenetic regulation of the genome (along with other environmental variables such as lead consumption, which causes abnormal behavior and also epigenetic changes which can be passed through the generations; Senut et al, 2012; Sen et al, 2015) which then leads to impaired brain development, which then leads to externalizing behavior, internalizing behavior and autism and schizophrenia (two disorders which are also affected by the microbiome; Strati et al, 2017; Dickerson, 2017).

Clearly, since the food we eat gives us access to certain fatty acids that cannot be produced de novo in the brain or body, good nutrition is needed for a developing brain and if certain pertinent vitamins, minerals or fatty acids are missing, negative outcomes could occur for said individual in the future due to lack of brain development from being nutrient, vitamin, and mineral deficient in childhood. Further, interactions between nutrient deficiencies and exposure to toxic chemicals may be a cause of a large amount of antisocial behavior (Walsh et al, 1997; Hubbs-Tait et al, 2005; Firth et al, 2017).

Looking for a cause for this interaction between metal consumption and nutrient deficiencies, Liu, Zhao, and Reyes (2015) state that since protein and fatty acids are essential to brain growth, lack of consumption of pertinent micro- and macro-nutrients along with consumption of high amounts of protein both in and out of the womb contribute to lack of brain growth and, at adulthood, explains part of the difference in antisocial behavior. What you can further see from the above studies is that metals consumed by an individual can interact with the nutrient deficiencies in said individual and cause more deleterious outcomes, since, for example, lead is a nutrient antagonist—that is, it inhibits the physiologic actions of whatever bioavailable nutrients are available to the body for us.

Good nutrition is, of course, imperative since it gives our bodies what it needs to grow and develop as we grow in the womb, as adolescents and even into old age. So, therefore, developing people who are nutrient deficient will have worse behavioral outcomes. Further, lower class people are more likely to be nutrient deficient and consume lower quality diets than higher, more affluent classes, though it’s hard to discover which way the causation goes (Darmon and Drewnowski, 2008). Of course, the logical conclusion is that being deficient in vitamins, minerals and EFAs causes changes to the epigenome and retards brain development, therefore this has a partly causal effect on future antisocial, violent and criminal behavior. So, some of the crime difference between classes can be attributed to differences in nutrition/toxic metal exposure that induces epigenetic changes that change the structure of the brain and doesn’t allow full brain development due to lack of vitamins, minerals, and EFAs.

There seems to be a causal effect on criminal, violent and antisocial behavior regarding nutrient deficiencies in both juveniles and adults (which starts in the womb and continues into adolescence and adulthood). However, it has been shown in a few randomized controlled trials that nutritional interventions decrease some antisocial behavior, with the effect being strongest for those individuals who showed worse nutrient deficiencies.

If the relationship between nutrition/interaction between nutrient deficiencies and toxins can be replicated successfully then this leads us to one major question: Are we, as a society, in part, causing some of the differences in crime due to how our society is regarding nutrition and the types of food that are advertised to our youth? Are people’s diets which lead to nutrient deficiencies a driving factor in causing crime? The evidence so far on nutrition and its effects on the epigenome and its effects on the growth of the brain in the womb and adolescence requires us to take a serious look at this relationship. That lower class people are exposed to more neurotoxins such as lead (Bellinger, 2008) and are more likely to be nutrient deficient (Darmon and Drewnowski, 2008; Hackman, Farrah, and Meaney, 2011) then if they were educated on which foods to eat to avoid nutrient deficiencies along with avoiding neurotoxins such as lead (which exacerbate nutrient deficiencies and cause crime), then a reduction in crime should occur.

Nutrition is important for all living beings; and as can be seen, those who are deficient in certain nutrients and have less access to good, whole, nutritious food (who also have an increased risk for exposure to neurotoxins) can lead to negative outcomes. These things can be prevented, it seems, with a few vitamins/minerals/EFA consumption. The effects of sleep, poor diet (which also lead to metabolic syndromes) can also exacerbate this relationship, between individuals and ethnicities. The relationship between violence and antisocial behavior and nutrient deficiencies/the interaction with nutrient deficiencies and neurotoxins is a great avenue for future research to reduce violent crime in our society. Lower class people, of course, should be the targets of such interventions since there seems to be a causal effect—-however small or large—on behavior, both violent and nonviolent—and so nutrition interventions should close some of the crime gaps between classes.

Conclusion

The logic is very simple: nutrition affects mood (Rao et al, 2008; Jacka, 2017) which is, in part, driven by the microbiome’s intimate relationship with the brain (Clapp et al, 2017; Singh et al, 2017); nutrition also affects the epigenome and the growth and structure of the brain if vitamin and mineral needs are not met by the growing body. This then leads to differences in gene expression due to the foods consumed, the microbiome (which also influences the epigenome) further leads to differences in gene expression and behavior since the two are intimately linked as well. Thus, the aetiology of certain behaviors may come down to nutrient deficiencies and complex interactions between the environment, neurotoxins, nutrient deficiencies and genetic factors. Clearly, we can prevent this with preventative nutritional education, and since lower class people are more likely to suffer the most from these problems, the measures targeted to them, if followed through, will lower incidences of crime and antisocial/violent behavior.

Does Playing Violent Video Games Lead to Violent Behavior?

1400 words

President Trump was quoted the other day saying “We have to look at the Internet because a lot of bad things are happening to young kids and young minds and their minds are being formed,” Trump said, according to a pool report, “and we have to do something about maybe what they’re seeing and how they’re seeing it. And also video games. I’m hearing more and more people say the level of violence on video games is really shaping young people’s thoughts.” But outside of broad assertions like this—that playing violent video games cause violent behavior—does it stack up to what the scientific literature says about it? In short, no, it does not. (A lot of publication bias exists in this debate, too.) Why do people think that violent video games cause violent behavior? Mostly due to the APA and their broad claims with little evidence.