Home » 2018 (Page 4)

Yearly Archives: 2018

Somatotyping, Constitutional Psychology, and Sports

1600 words

In the 1940s, psychologist William Sheldon created a system of body measures known as “somatotyping”, then took his somatotypes and attempted to classify each soma (endomorph, ectomorph, or mesomorph) to differing personality types. It was even said that “constitutional psychology can guide a eugenics program and save the modern world from itself.”

Sheldon attempted to correlate different personality dimensions to different somas. But his somas fell out of favor before being revived by two of his disciples—without the “we-can-guess-your-personality-from-your-body-type” canard that Sheldon used. Somatotyping, while of course being put to use in a different way today compared to what it was originally created for, it gives us reliable dimensions for human appendages and from there we can ascertain what a given individual would excel at in regard to sporting events (obviously this is just on the basis of physical measures and does not measure the mind one needs to excel in sports).

The somatotyping system is straightforward: You have three values, say at 1-1-7; the first refers to endomorphy, the second refers to mesomorphy and the third refers to ectomorphy, therefore a 1-1-7 would be an extreme ectomorph. However, few people are at the extreme end of each soma, and most people have a combination of two or even all three of the somas.

According to Carter (2002): “The somatotype is defined as the quantification of the present shape and composition of the human body.” So, obviously, somas can change over time. However, it should be noted that the somatotype is, largely, based on one’s musculoskeletal system. This is where the appendages come in, along with body fat, wide and narrow clavicles and chest etc. This is why the typing system, although it began as a now-discredited method, should still be used today since we do not use the pseudoscientific personality measures with somatotyping.

Ectomorphs are long and lean, lanky, you could say. They have a smaller, narrower chest and shoulders, along with longer arms and legs, and have a hard time gaining weight, and a short upper body (I’d say they have a harder time gaining weight due to a slightly faster metabolism, in the variation of the normal range of metabolism, of course). Put simply, ectomorphs are just skinny and lanky with less body fat than mesos and endos. Human races that fit this soma are East Africans and South Asians (see Dutton and Lynn, 2015; one of my favorite papers from Lynn for obvious reasons).

Endomorphs are stockier, shorter and have wider hips, along with short limbs, a wider trunk, more body fat and can gain muscular strength easier than the other somas. Thus, endos, being shorter than ectos and mesos, have a lower center of gravity, along with shorter arms. Thus, we should see that these somas dominate strongman competitions and this is what we see. Pure strength competitions are perfect for this type, such as Strongman competitions and powerlifting. Races that generally conform to this type are East Asians, Europeans, and Pacific Islanders (see Dutton and Lynn, 2015).

Finally, we have mesomorphs (the “king” of all of the types). Mesos are more muscular on average than the two others, they have less body fat than endos but more body fat than ectos; they have wider shoulders, chest and hips, a short trunk and long limbs. The most mesomorphic races are West Africans (Malina, 1969), and due to their somatotype they can dominate sprinting competitions; they also have thinner skin folds (Vickery, Cureton, and Collins, 1988; Wagner and Heyward, 2000), and so they would have an easier time excelling at running competitions but not at weightlifting, powerlifting, or Strongman (see Dutton and Lynn, 2015).

These anatomic differences between the races of man are due to climatic adaptations. The somatypic differences Neanderthals and Homo sapiens mirror the somatotype difference between blacks and whites; since Neanderthals were cold-adapted, they were shorter, had wider pelves and could thusly generate more power than the heat-adapted Homo sapiens who had long limbs and narrow pelvis to better dissipate heat. Either way, we can look at the differences in somatotype between races that evolved in Europe and Africa to ascertain the somatotype of Neanderthals—and we also have fossil evidence for these claims, too (see e.g., Weaver and Hublin, 2009; Gruss and Schmitt, 2016)

Now, just because somatotyping, during its conception, was mixed with pseudoscientific views about differing somas having differing psychological types, does not mean that these differences in body type do not have any bearing on sporting performance. We can chuck the “constitutional psychology” aspect of somatotyping and just keep the anthropometric measures, and, along with the knowledge of human biomechanics, we can then discuss, in a scientific manner, why one soma would excel in sport X or why one soma would not excel in sport X. Attempting to argue that since somatotyping began as some crank psuedoscience does not mean that it is not useful today, since we do not ascribe inherent psychological differences to these somas (I’d claim that saying that this soma has a harder time gaining weight compared to that soma is not ascribing a psychological difference to the soma; it is taking physiologically and on average we can see that different somas have different propensities for weight gain).

In her book Straightening the Bell Curve: How Stereotypes about Black Masculinity Drive Research about Race and Intelligence, Hilliard (2012: 21) discusses the pitfalls of somatotyping and how Sheldon attempted to correlate personality measures with his newfound somatotypes:

As a young graduate student, he [Richard Herrnstein] had fallen under the spell of Harvard professor S. S. Stevens, who had coauthored with William Sheldon a book called The Varieties of Temperament: A Psychology of Constitutional Differences, which popularized the concept of “somatotyping,” first articulated by William Sheldon. This theory sought, through the precise measurement and analysis of human body types, to establish correlations comparing intelligence, temperament, sexual proclivities, and the moral worth of individuals. Thus, criminals were perceived to be shorter and heavier and more muscular than morally upstanding citizens. Black males were reported to rank higher on the “masculine component” scale than white males did, but lower in intelligence. Somatotyping lured the impressionable young Herrnstein into a world promising precision and human predictability based on the measuring of body parts.

Though constitutional psychology is now discredited, there may have been something to some of Sheldon’s theories. Ikeda et al (2018: 3) conclude in their paper, Re-evaluating classical body type theories: genetic correlation between psychiatric disorders and body mass index, that “a trans-ancestry meta-analysis of the genetic correlation between psychiatric disorders and BMI indicated that the negative correlation with SCZ supported classical body type theories proposed in the last century, but found a negative correlation between BD and BMI, opposite to what would have been predicted.” (Though it should be noted that SCZ is a, largely if not fully, environmentally-induced disorder, see Joseph, 2017.)

These different types (i.e., the differing limb lengths/body proportions) have implications for sporting performance. Asfaw and A (2018) found that Ethiopian women high jumpers had the highest ectomorph values whereas long and triple jumpers were found to be more mesomorphic. Sports good for ectos are distance running due to their light frame, tennis etc—anything that the individual can use their light frame as an advantage. Since they have longer limbs and a lighter frame, they can gain more speed in the run up to the jump, compared to endos and mesos (who are heavier). This shows why ectos have a biomechanical advantage when it comes to high jumping.

As for mesomorphs, the sports they excel at are weightlifting, powerlifting, strongman, football, rugby etc. Any sport where the individual can use their power and heavier bone mass will they excel in. Gutnik et al (2017) even concluded that “These results suggest with high probability that there is a developmental tendency of change in different aspects of morphometric phenotypes of selected kinds of sport athletes. These phenomena may be explained by the effects of continuous intensive training and achievement of highly sport-defined shapes.” While also writing that mesomorphy could be used to predict sporting ability.

Finally, for endomorphs, they too would excel in weightlifting, powerlifting, and strongman, but do on average better since they have different levers (i.e., shorter appendages so they can more weight and a shorter amount of time in comparison to those with longer limbs like ectos).

Thus, different somatotypes excel in different sports. Different races and ethnies have differing somatotypes (Dutton and Lynn, 2015), so these different bodies that the races have, on average, is part of the cause for differences in sporting ability. That somatotyping began as a pseudoscientific endeavor 70 years ago does not mean that it does not have a use in today’s world—because it clearly does due to the sheer amount of papers on the usefulness of somatotyping and relating differences in sporting performance due to somatotyping. For example, blacks have thinner skin folds (Vickery, Cureton, and Collins, 1988; Wagner and Heyward, 2000) which is due to their somatotype, which is then due to the climate their ancestors evolved in.

Somatotyping can show us the anthropometric reasons for how and why certain individuals, ethnies, and races far-and-away dominate certain sporting events. It is completely irrelevant that somatotyping began as a psychological pseudoscience (what isn’t in psychology, am I right?). Understanding anthropometric differences between individuals and groups will help us better understand the evolution of these somas along with how and why these somas lead to increased sporting performance in certain domains. Somatotyping has absolutely nothing to do with “intelligence” nor how morally upstanding one is. I would claim that somatotyping does have an effect on one’s perception of masculinity, and thus more masculine people/races would tend to be more mesomorphic, which would explain what Hilliard (2012) discussed when talking about somatotyping and the attempts to correlate differing psychological tendencies to each type.

Blumenbachian Partitions and Mimimalist Races

2100 words

Race in the US is tricky. On one hand, we socially construct races. On the other, these socially constructed races have biological underpinnings. Racial constructivists, though, argue that even though biological races are false, races have come into existence—and continue to exist—due to human culture and human decisions (see the SEP). Sound arguments exist for the existence of biological races. Biological races exist, and they are real. One extremely strong view is from philosopher of science Quayshawn Spencer. In his paper A Radical Solution to the Race Problem, Spencer (2014) argues that biological races are real; that the term “race” directly refers; that race denotes proper names, not kinds; and these sets of human populations denoted by Americans can be denoted as a partition of human populations which Spencer (2014) calls “the Blumenbach partition”.

To begin, Spencer (2014) defines “referent”: “If, by using appropriate evidential methods (e.g., controlled experiments), one finds that a term t has a logically inconsistent set of identifying conditions but a robust extension, then it is appropriate to identify the meaning

of t as just its referent.” What he means is that the word “race” is just a referent, which means that the term “race” lies in what points out in the world. So, what “race” points out in the world becomes clear if we look at how Americans define “race”.

Spencer (2014) assumes that “race” in America is the “national meaning” of race. That is, the US meaning of race is just the referent to the Census definitions of race, since race-talk in America is tied to the US Census. But the US Census Bureau defers to the Office of Management and Budget (OMB). Therefore, since the US Census Bureau defers to the OMB on matters of race, and since Americans defer to the US Census Bureau, then Americans use the OMB definitions of race.

The OMB describes a “comprehensive set” of categories (according to the OMB) which lead Spencer (2014) to believe that the OMB statements on race are pinpointing Caucasians, Africans, Pacific Islanders, East Asians, and Amerindians. Spencer (2014: 1028-29) thusly claims that race in America “is a term that rigidly designates a particular set of “population groups.” Now, of course, the question is this: are these population groups socially constructed? Do they really exist? Are the populations identified arbitrary? Of course, the answer is that they identify a biologically real set of population groups.

To prove the existence of his Blumenbachian populations, Spencer (2014) invokes populational genetic analyses. Population geneticists first must make the assumption at how many local populations exist in the target species. According to Spencer, “The current estimate for humans is 7,105 ethnic groups, half of which are in Africa and New Guinea.” After the assumptions are made, the next step is to sample the species’ estimated local populations. Then they must test noncoding DNA sequences. Finally, they must attempt to partition the sample so that each partition at each level is unique which then minimizes genetic differences in parts and maximizes genetic differences among parts. There are two ways of doing this: using structure and PCA. For the purposes of this argument, Spencer (2014) chooses structure, invoking a 5-population racial model, (see e.g., Rosenberg et al, 2002).

K = 5 corresponds to 5 populational clusters which denote Africans, Oceanians, East Asians, Amerindians, and Caucasians (Spencer, 2014; Hardimon, 2017b). K = 5 shows that the populations in question are genetically structured—that is, meaningfully demarcated on the basis of genetic markers and only genetic markers. Thus, that the populations in question are meaningfully demarcated on the basis of genetic markers, this is evidence that Hardimon’s (2017b) minimalist races are a biological reality. Furthermore, since Rosenberg et al (2002) used microsatellite markers in their analysis, this is a nonarbitrary way of constructing genetic clusters which then demarcate the continental-level minimalist races (Hardimon, 2017b: 90).

Thus, Spencer (2014) argues to call the partition identified in K = 5 “the Blumenbachian partition” in honor of Johann Blumenbach, anthropologist, physician, physiologist, and naturalist. (Though it should be noted that one of his races “Malays” was not a race, but Oceaninans are, so he “roughly discovered” the population partition.) So we can say that “the Blumenbach partition” is just the US meaning of “race”, the partitions identified by K = 5 (Rosenberg et al, 2002).

Furthermore, like Lewontin (1972), Rosenberg et al (2002) found that a majority of human genetic variation is between individuals, not races. That is, Rosenberg et al (2002) found that only 4.3 percent of human genetic variation was found to lie between the continental-level minimalist races. Thus, minimalist races are a biological kind, “if only a modest one” (Hardimon, 2017b: 91). Thus, Rosenberg et al (2002) support the contention that minimalist races exist and are a biological reality since a fraction of human population variation is due to differences among continental-level minimalist races (Africans, Caucasians, East Asians, Oceanians, and Amerindians). The old canard is true, there really is more genetic variation within races than between them, but, as can be seen, that does not rail against the reality of race, since that small amount of genetic variation shows that humanity is meaningfully clustered in a genetic sense.

Spencer (2014: 1032) then argues why Blumenbachian populations are “race” in the American sense:

It is not hard to generate accessible possible worlds that support the claim that US race terms are just aliases for Blumenbachian populations. For example, imagine a possible world τ where human history unfolded exactly how it did in our world except that every Caucasian in τ was killed by an infectious disease in the year 2013. Presumably, we have access to τ, since it violates no logical, metaphysical, or scientific principles. Then, given that we use ‘white’ in its national American meaning in our world, and given that we use ‘Caucasian’ in its Blumenbachian meaning in our world, it is fair to say that both ‘Caucasian’ and ‘white’ are empty terms in τ in 2014—which makes perfect sense if ‘white’ is just an alias for Caucasians. It is counterfactual evidence like this that strongly suggests that the US meaning of ‘race’ is just the Blumenbach partition.

Contrary to critics, this partition is biologically real and demarcates the five genetically structured populations of the human race. Rosenberg et al (2005) found that if sufficient data are used, “the geographic distribution of the sampled individuals has little effect on the analysis“, while their results verify that genetic clusters “arise from genuine features of the underlying pattern of human genetic variation, rather than as artifacts of uneven sampling along continuous gradients of allele frequencies.”

Some may claim that K = 5 is “arbitrary”, however, constructing genetic clusters using microsatellites is nonarbitrary (Hardimon, 2017b: 90):

Constructing genetic clusters using microsatellites constitutes a nonarbitrary way of demarcating the boundaries of continental-level minimalist races. And the fact that it is possible to construct genetic clusters corresponding to continental-level minimalist races in a nonarbitrary way is itself a reason for thinking that minimalist race is biologically real 62.

It should also be noted that Hardimon writes in note 62 (2017b: 197):

Just to be perfectly clear, I don’t think that the results of the 2002 Rosenberg article bear on the question: Do minimalist races exist? That’s a question that has to be answered separately. In my view, the fundamental question in the philosophy of race on which the results of this study bear is whether minimalist race is biologically real. My contention is that they indicate that minimalist race (or more precisely, continental-level minimalist race) is biologically real if sub-Saharan Africans, Caucasians, East Asians, Amerindians, and Oceanians constitute minimalist races.

Sub-Saharan Africans, Caucasians, East Asians, Amerindians, and Oceanians constitute minimalist races, therefore race is a biological reality. We can pinpoint them on the basis of patterns of visible physical features; these visible physical features correspond to geographic ancestry; this satisfies the criteria for minimalist races; therefore race exists. Race exists as a biological kind.

Furthermore, if these five populations that Rosenberg et al (2002) identified (the Blumenbachian populations) are minimalist races, then minimalist race is “a minor principle of human genetic structure” (Hardimon, 2017b: 92). Since minimalist races constitute a dimension within the small amount of human genetic variation that is captured between the continental-level minimalist races (4.3 percent), then it is completely possible to talk meaningfully about the racial structure of human genetic variation which consists of the human genetic variation which corresponds to continental-level minimalist races.

Thus, the US meaning of race is just a referent; the US meaning of race refers to a particular set of human populations; races in the US are classically-defined races (Amerindian, Caucasian, African, East Asian, and Oceanians; the Blumenbach partition); and race is both a biological reality as well as socially constructed. These populations are biologically real; if these populations are biologically real, then it stands to reason that biological racial realism is true (Hardimon, 2012 2013, 2017a; 2017b; Spencer, 2014, 2015).

Human races exist, in a minimalist biological sense, and there are 5 human races. Defenders of Rushton’s work—who believed there are only 3 primary races: Caucasoids, Mongoloids, and Negroids (while Amerindians and others were thrown into the “Mongoloid race” and Pacific Islanders being grouped with the “Negroid race” (Rushton, 1988, 1997; see also Liberman, 2001 for a critique of Rushton’s tri-racial views)—are forced into a tri-racial theory, since he used this tri-racial theory as the basis for his, now defunct, r/K selection theory. The tri-racial theory, that there are three primary races of man—Caucasoid, Mongoloid, and Negroid—has fallen out of favor with anthropologists for decades. But what we can see from new findings in population genetics since the sequencing of the human genome, however, is that human populations cluster into five populations and these five populations are races, therefore biological racial realism is true.

Biological racial realism (the fact that race exists as a biological reality) is true, however, just like with Hardimon’s minimalist races, they do not denote “superiority”, “inferiority” for one race over another. Most importantly, Blumenbachian populations do not denote those terms because the genetic evidence that is used to support the Blumenbachian partition use noncoding DNA. (It should also be noted that the terms “superior” and “inferior” are nonsensical, when used outside of their anatomic contexts. The head is the most superior part of the human body, the feet are the most inferior part of the human body. This is the only time these terms make sense, thus, using the terms outside of this context makes no sense.)

It is worth noting that, while Hardimon’s and Spencer’s views on race are similar, there are some differences between their views. Spencer sees “race” as a referent, while Hardimon argues that race has a set descriptive meaning on the basis of C (1)-(3); (C1) that, as a group, is distinguished from other groups of human beings by patterns of visible physical features, (C2) whose members are linked be a common ancestry peculiar to members of that group, and (C3) that originates from a distinctive geographic location” (Hardimon, 2017b: 31). Whether or not one prefers Blumenbachian partitions or minimalist races depends on whether or not one prefers race in a descriptive sense (i.e., Hardimon’s minimalist races) or if the term race in America is a referent to the US Census discourse, which means that “race” refers to the OMB definitions which then denote Blumenbachian partitions.

Hardimon also takes minimalist races to be a biological kind, while Spencer takes them to be a proper name for a set of population groups. Both of these differing viewpoints regarding race, while similar, are different in that one is describing a kind, while the other describes a proper name for a population group; these two views regarding population genetics from these two philosophers are similar, they are talking about the same things and hold the same deflationary views regarding race. They are talking about how race is seen in everyday life and where people get their definitions of “race” from and how they then integrate it into their everyday lives.

“Race” in America is a proper name for a set of human population groups, the five population groups identified by K = 5. Americans defer to the US Census Bureau on race, who defers to the Office of Management and Budget to define race. They hold that races are a “set”, and these “sets” are Oceanians, Caucasians, East Asians, Amerindians, and Africans. Race, thusly, refers to a set of population groups; “race” is not a “kind”, but a proper name for known populational groups. K = 5 then shows us that the demarcated clusters correspond to continental-level minimalist races, what is termed “the Blumenbach partition.” This partition is “race” in the US sense of the term, and it is a biological reality, therefore, like Hardimon’s minimalist races, the Blumenbach partition identifies what we in America know to be race. (It’s worth noting that, obviously, the Blumenbach partition/minimalist races are one in the same, Spencer is a deflationary realist regarding race, just like Hardimon.)

Defending Minimalist Races: A Response to Joshua Glasgow

2000 words

Michael Hardimon published Rethinking Race: The Case for Deflationary Realism last year (Hardimon, 2017). I was awaiting some critical assessment of the book, and it seems that at the end of March, some criticism finally came. The criticism came from another philosopher, Joshua Glasgow, in the journal Mind (Glasgow, 2018). The article is pretty much just arguing against his minimalist race concept and one thing he brings up in his book, the case of a twin earth and what we would call out-and-out clones of ourselves on this twin earth. Glasgow makes some good points, but I think he is largely misguided on Hardimon’s view of race.

Hardimon (2017) is the latest defense for the existence of race—all the while denying the existence of “racialist races”—that there are differences in mores, “intelligence” etc—and taking the racialist view and “stripping it down to its barebones” and shows that race exists, in a minimal way. This is what Hardimon calls “social constructivism” in the pernicious sense—racialist races, in Hardimon’s eyes, are socially constructed in a pernicious sense, arguing that racialist races do not represent any “facts of the matter” and “supports and legalizes domination” (pg 62). The minimalist concept, on the other hand, does not “support and legalize domination”, nor does it assume that there are differences in “intelligence”, mores and other mental characters; it’s only on the basis of superficial physical features. These superficial physical features are distributed across the globe geographically and these groups are real and exist who show these superficial physical features across the globe. Thus, race, in a minimal sense, exists. However, people like Glasgow have a few things to say about that.

Glasgow (2018) begins by praising Hardimon (2017) for “dispatching racialism” in his first chapter, also claiming that “academic writings have decisively shown why racialism is a bad theory” (pg 2). Hardimon argues that to believe in race, on not need believe what the racialist concept pushes; one must only acknowledge and accept that there are:

1) differences in visible physical features which correspond to geographic ancestry; 2) these differences in visible features which correspond to geographic ancestry are exhibited between real groups; 3) these real groups that exhibit these differences in physical features which correspond to geographic ancestry satisfy the conditions of minimalist race; C) therefore race exists.

This is a simple enough argument, but Glasgow disagrees. As a counter, Glasgow brings up the “twin earth” argument. Imagine a twin earth was created. On Twin Earth, everything is exactly the same; there are copies of you, me, copies of companies, animals, history mirrored down to exact minutiae, etc. The main contention here is that Hardimon claims that ancestry is important for our conception of race. But with the twin earth argument, since everything, down to everything, is the same, then the people who live on twin earth look just like us but! do not share ancestry with us, they look like us (share patterns of visible physical features), so what race would we call them? Glasgow thusly states that “sharing ancestry is not necessary for a group to count as a race” (pg 3). But, clearly, sharing ancestry is important for our conception of race. While the thought experiment is a good one it fails since ancestry is very clearly necessary for a group to count as a race, as Hardimon has argued.

Hardimon (2017: 52) addresses this, writing:

Racial Twin Americans might share our concept of race and deny that races have different geographical origins. This is because they might fail to understand that this is a component of their race concept. If, however, their belief that races do not have different geographical origins did not reflect a misunderstanding of their “race concept,” then their “race concept” would not be the same concept as the concept that is the ordinary race concept in our world. Their use of ‘race’ would pick out a different subject matter entirely from ours.

and on page 45 writes:

Glasgow envisages Racial Twin Earth in such a way that, from an empirical (that is, human) point of view, these groups would have distinctive ancestries, even if they did not have distinctive ancestries an sich. But if this is so, the groups [Racial Twin Earthings] do not provide a good example of races that lack distinctive ancestries and so do not constitute a clear counterexample to C(2) [that members of a race are “linked by a common ancestry peculiar to members of that group”].

C(2) (P2 in the simple argument for the existence of race) is fine, and the objections from Glasgow do not show that P(C)2 is false at all. The Racial Twin Earth argument is a good one, it is sound. However, as Hardimon had already noted in his book, Glasgow’s objection to C(2) does not rebut the fact that races share peculiar ancestry unique to them.

Next, Glasgow criticizes Hardimon’s viewpoints on “Hispanics” and Brazilians. These two groups, says Glasgow, shows that two siblings with the same ancestry, though they have different skin colors, would be different races in Brazil. He uses this example to state that “This suggests that race and ancestry can be disconnected” (pg 4). He criticizes Hardimon’s solution to the problem of race and Brazilians, stating that our term “race” and the term in Brazil do not track the same things. “This is jarring. All that anthropological and sociological work done to compare Brazil with the rest of the world (including the USA) would be premised on a translation error” (pg 4). Since Americans and Brazilians, in Glasgow’s eyes, can have a serious conversation about race, this suggests to Glasgow that “our concept of race must not require that races have distinct ancestral groups” (pg 5).

I did cover Brazilians and “Hispanics” as regards the minimalist race concept. Some argue that the “color system” in Brazil is actually a “racial system” (Guimaraes 2012: 1160). While they do denote race as ‘COR’ (Brazilian for ‘color), one can argue that the term used for ‘color’ is ‘race’ and that we would have no problem discussing ‘race’ with Brazilians, since Brazilians and Americans have similar views on what ‘race’ really is. Hardimon (2017: 49) writes:

On the other hand, it is not clear that the Brazilian concept of COR is altogether independent of the phenomenon we Americans designate using ‘race.’ The color that ‘COR’ picks out is racial skin color. The well-known, widespread preference for lighter (whiter) skin in Brazil is at least arguably a racial preference. It seems likely that white skin color is preferred because of its association with the white race. This provides a reason for thinking that the minimalist concept of race may be lurking in the background of Brazilian thinking about race.

Since ‘COR’ picks out racial skin color, it can be safely argued that Brazilians and Americans at least are generally speaking about the same things. Since the color system in Brazil pretty much mirrors what we know as racial systems, demarcating races on the basis of physical features, we are, it can be argued, talking about the same (or similar) things.

Further, the fact that “Latinos” do not fit into Hardimon’s minimalist race concepts is not a problem with Hardimon’s arguments about race, but is a problem with how “Latinos” see themselves and racialize themselves as a group. “Latinos” can count as a socialrace, but they do not—can not—count as a minimalist race (such as the Caucasian minimalist race; the African minimalist race; the Asian minimalist race etc), since they do not share visible physical patterns which correspond to differences in geographic ancestry. Since they do not exhibit characters that demarcate minimalist races, they are not minimalist races. Looking at Cubans compared to, say, Mexicans (on average) is enough to buttress this point.

Glasgow then argues that there are similar problems when you make the claim “that having a distinct geographical origin is required for a group to be a race” (pg 5). He says that we can create “Twin Trump” and “Twin Clinton” might be created from “whole cloth” on two different continents, but we would still call them both “white.” Glasgow then claims that “I worry that visible trait groups are not biological objects because the lines between them are biologically arbitrary” (pg 5). He argues that we need a “dividing line”, for example, to show that skin color is an arbitrary trait to divide races. But if we look at skin color as an adaptation to the climate of the people in question (Jones et al, 2018), then this trait is not “arbitrary”, and the trait is then linked to geographic ancestry.

Glasgow then goes down the old and tired route that “There is no biological reason to mark out one line as dividing the races rather than another, simply based on visible traits” (pg 5). He then goes on to discuss the fact that Hardimon invokes Rosenberg et al (2002) who show that our genes cluster in specific geographic ancestries and that this is biological evidence for the existence of race. Glasgow brings up two objections to the demarcation of races on both physical appearance and genetic analyses: picture the color spectrum, “Now thicken the orange part, and thin out the light red and yellow parts on either side of orange. You’ve just created an orange ‘cluster’” (pg 6), while asking the question:

Does the fact that there are more bits in the orange part mean that drawing a line somewhere to create the categories orange and yellow now marks a scientifically principled line, whereas it didn’t when all three zones on the spectrum were equally sized?

I admit this is a good question, and that this objection would indeed go with the visible trait of skin color in regard to race; but as I said above, since skin color can be conceptualized as a physical adaptation to climate, then that is a good proxy for geographic ancestry, whether or not there is a “smooth variation” of skin colors as you move away from the equator or not, it is evidence that “races” have biological differences and these differences start on the biggest organ in the human body. This is just the classic continuum fallacy in action: that X and Y are two different parts of an extreme; there is no definable point where X becomes Y, therefore there is no difference between X and Y.

As for Glasgow’s other objection, he writes (pg 6):

if we find a large number of individuals in the band below 62.3 inches, and another large grouping in the band above 68.7 inches, with a thinner population in between, does that mean that we have a biological reason for adopting the categories ‘short’ and ‘tall’?

It really depends on what the average height is in regard to “adopting the categories ‘short’ and ‘tall’” (pg 6). The first question was better than the second, alas, they do not do a good job of objecting to Hardimon’s race concept.

In sum, Glasgow’s (2018) review of Hardimon’s (2017) book Rethinking Race: The Case for Deflationary Realism is an alright review; though Glasgow leaves a lot to be desired and I do think that his critique could have been more strongly argued. Minimalist races do exist and are biologically real.

I am of the opinion that what matters regarding the existence of race is not biological science, i.e., testing to see which populations have which differing allele frequencies etc; what matters is the philosophical aspects to race. The debates in the philosophical literature regarding race are extremely interesting (which I will cover in the future), and are based on racial naturalism and racial eliminativism.

(Racial naturalism “signifies the old, biological conception of race“; racial eliminativism “recommends discarding the concept of race entirely“; racial constructivism “races have come into existence and continue to exist through “human culture and human decisions” (Mallon 2007, 94)“; thin constructivism “depicts race as a grouping of humans according to ancestry and genetically insignificant, “superficial properties that are prototypically linked with race,” such as skin tone, hair color and hair texture (Mallon 2006, 534); and racial skepticism “holds that because racial naturalism is false, races of any type do not exist“.) (Also note that Spencer (2018) critiques Hardimon’s viewpoints in his book as well, which will also be covered in the future, along with the back-and-forth debate in the philosophical literature between Quayshawn Spencer (e.g., 2015) and Adam Hochman (e.g., 2014).)

Black-White Differences in Anatomy and Physiology: Black Athletic Superiority

3000 words

Due to evolving in different climates, the different races of Man have differing anatomy and physiology. This, then, leads to differences in sports performance—certain races do better than others in certain bouts of athletic prowess, and this is due to, in large part, heritable biological/physical differences between blacks and whites. Some of these differences are differences in somatotype, which bring a considerable advantage for, say, runners (an ecto-meso, for instance, would do very well in sprinting or distance running depending on fiber typing). This article will discuss differences in racial anatomy and physiology (again) and how it leads to disparities in certain sports performance.

Kerr (2010) argues that racial superiority in sport is a myth. (Read my rebuttal here.) In his article, Kerr (2010) attempts to rebut Entine’s (2000) book Taboo: Why Black Athletes Dominate Sports and Why We’re Afraid to Talk About It. In a nutshell, Kerr (2010) argues that race is not a valid category; that other, nongenetic factors play a role other than genetics (I don’t know if anyone has ever argued if it was just genetics). Race is a legitimate biological category, contrary to Kerr’s assertions. Kerr, in my view, strawman’s Entine (2002) by saying he’s a “genetic determinist”, but while he does discuss biological/genetic factors more than environmental ones, Entine is in no way a genetic determinist (at least that’s what I get from my reading of his book, other opinions may differ). Average physical differences between races are enough to delineate racial categories and then it’s only logical to infer that these average physical/physiological differences between the races (that will be reviewed below) would infer an advantage in certain sports over others, while the ultimate cause was the environment that said race’s ancestors evolved in (causing differences in somatotype and physiology).

Black athletic superiority has been discussed for decades. The reasons are numerous and of course, this has even been noticed by the general public. In 1991, half of the respondents of a poll on black vs. whites in sports “agreed with the idea that “blacks have more natural physical ability,“” (Hoberman, 1997: 207). Hoberman (1997) of course denies that there is any evidence that blacks have an advantage over whites in certain sports that come down to heritable biological factors (which he spends the whole book arguing). However, many blacks and whites do, in fact, believe in black athletic superiority and that physiologic and anatomic differences between the races do indeed cause racial differences in sporting performance (Wiggins, 1989). Though Wiggins (1989: 184) writes:

The anthropometric differences found between racial groups are usually nothing more than central tendencies and, in addition, do not take into account wide variations within these groups or the overlap among members of different races. This fact not only negates any reliable physiological comparisons of athletes along racial lines, but makes the whole notion of racially distinctive physiological abilities a moot point.

This is horribly wrong, as will be seen throughout this article.

The different races have, on average, differing somatotypes which means that they have different anatomic proportions (Malina, 1969):

| Data from Malina, (1969: 438) | n | Mesomorph | Ectomorph | Endomorph |

| Blacks | 65 | 5.14 | 2.99 | 2.92 |

| Whites | 199 | 4.29 | 2.89 | 3.86 |

| Data from Malina (1969: 438) | Blacks | Whites |

| Thin-build body type | 8.93 | 5.90 |

| Submedium fatty development | 48.31 | 29.39 |

| Medium fleshiness | 33.69 | 43.63 |

| Fat and very fat categories | 9.09 | 21.06 |

This was in blacks and whites aged 6 to 11. Even at these young ages, it is clear that there are considerable anatomic differences between blacks and whites which then lead to differences in sports performance, contra Wiggins (1989). A basic understanding of anatomy and how the human body works is needed in order to understand how and why blacks dominate certain sports over whites (and vice versa). Somatotype is, of course, predicated on lean mass, fat mass, bone density, stature, etc, which are heritable biological traits, thus, contrary to popular belief that somatotyping holds no explanatory power in sports today (see Hilliard, 2012).

One variable that makes up somatotype is fat-free body mass. There are, of course, racial differences in fat mass, too (Vickery, Cureton, and Collins, 1988; Wagner and Heyward, 2000). Lower fat mass would, of course, impede black excellence in swimming, and this is what we see (Rushton, 1997; Entine, 2000). Wagner and Heyward (2000) write:

Our review unequivocally shows that the FFB of blacks and whites differs significantly. It has been shown from cadaver and in vivo analyses that blacks have a greater BMC and BMD than do whites. These racial differences could substantially affect measures of body density and %BF. According to Lohman (63), a 2% change in the BMC of the body at a given body density could, theoretically, result in an 8% error in the estimation of %BF. Thus, the BMC and BMD of blacks must be considered when %BF is estimated.

While Vickery, Cureton, and Collins (1988) found that blacks had thinner skin folds than whites, however, in this sample, somatotype did not explain racial differences in bone density, like other studies (Malina, 1969), Vickery, Cureton, and Collins (1988) found that blacks were also more likely to be mesomorphic (which would then express itself in racial differences in sports).

Hallinan (1994) surveyed 32 sports science, exercise physiology, biomechanics, motor development, motor learning, and measurement evaluation textbooks to see what they said racial differences in sporting performance and how they explained them. Out of these 32 textbooks, according to Wikipedia, these “textbooks found that seven [textbooks] suggested that there are biophysical differences due to race that might explain differences in sports performance, one [textbook] expressed caution with the idea, and the other 24 [textbooks] did not mention the issue.” Furthermore, Strklaj and Solyali (2010), in their paper “Human Biological Variation in Anatomy Textbooks: The Role of Ancestry” write that their “results suggest that this type of human variation is either not accounted for or approached only superficially and in an outdated manner.”

It’s patently ridiculous that most textbooks on the anatomy and physiology of the human body do not talk about the anatomic and physiologic differences between racial and ethnic groups. Hoberman (1997) also argues the same, that there is no evidence to confirm the existence of black athletic superiority. Of course, many hypotheses have been proposed to explain how and why blacks are at an inherent advantage in sport. Hoberman (1997: 269) discusses one, writing (quoting world record Olympian in the 400-meter dash, Lee Evans):

“We were bred for it [athletic dominance] … Certainly the black people who survived in the slave ships must have contained the highest proportion of the strongest. Then, on the plantations, a strong black man was mated with a strong black woman. We were simply bred for physical qualities.”

While Hoberman (1997: 270-1) also notes:

Finally, by arguing for a cultural rather than a biological interpretation of “race,” Edwards proposed that black athletic superiority results from “a complex of societal conditions” that channels a disproporitionate number of talented blacks into athletic careers.

The fact that blacks were “bred for” athletic dominance is something that gets brought up often but has little (if any) empirical support (aside from just-so stories about white slavemasters breeding their best, biggest and strongest black slaves). The notion that “a complex of societal conditions” (Edwards, 1971: 39) explains black dominance in sports, while it has some explanatory power in regard to how well blacks do in sporting competition, it, of course, does not tell the whole story. Edwards (1978: 39) argues that these complex societal conditions “instill a heightened motivation among black male youths to achieve success in sports; thus, they channel a proportionately greater number of talented black people than whites into sports participation.” While this may, in fact, be true, this does nothing to rebut the point that differences in anatomic and physiologic factors are a driving force in racial differences in sporting performance. However, while these types of environmental/sociological arguments do show us why blacks are over-represented in some sports (because of course motivation to do well in the sport of choice does matter), they do not even discuss differences in anatomy or physiology which would also be affecting the relationship.

For example, one can have all of the athletic gifts in the world, one can be endowed with the best body type and physiology to do well in any type of sport you can imagine. However, if he does not have a strong mind, he will not succeed in the sport. Lippi, Favaloro, and Guidi (2008) write:

An advantageous physical genotype is not enough to build a top-class athlete, a champion capable of breaking Olympic records, if endurance elite performances (maximal rate of oxygen uptake, economy of movement, lactate/ventilatory threshold and, potentially, oxygen uptake kinetics) (Williams & Folland, 2008) are not supported by a strong mental background.

Any athlete—no matter their race—needs a strong mental background, for if they don’t, they can have all of the physical gifts in the world, they will not become top-tier athletes in the sport of their choice; advantageous physical factors are imperative for success in differing sports, though myriad variables work in concert to produce the desired effect so you cannot have one without the other. On the other side, one can have a strong mental background and not have the requisite anatomy or physiology needed to succeed in the sport in question, but if he has a stronger mind than the individual with the requisite morphology, then he probably will win in a head-to-head competition. Either way, a strong mind is needed for strong performance in anything we do in life, and sport is no different.

Echoing what Hoberman (1997) writes, that “racist” thoughts of black superiority in part cause their success in sport, Sheldon, Jayaratne, and Petty (2007) predicted that white Americans’ beliefs in black athletic superiority would coincide with prejudice and negative stereotyping of black’s “intelligence” and work ethic. They studied 600 white men and women to ascertain their beliefs on black athletic superiority and the causes for it. Sheldon, Jayaratne, and Petty (2007: 45) discuss how it was believed by many, that there is a “ perceived inverse relationship between athleticism and intelligence (and hard work).” (JP Rushton was a big proponent of this hypothesis; see Rushton, 1997. It should also be noted that both Rushton, 1997 and Entine, 2000 believe that blacks’ higher rate of testosterone—3 to 15 percent— [Ross et al, 1986; Ellis and Nyborg, 1992; see rebuttal of both papers] causes their superior athletic performance, I have convincingly shown that they do not have higher levels of testosterone than other races, and if they do the difference is negligible.) However, in his book The Sports Gene: Inside the Science of Extraordinary Athletic Performance, Epstein (2014) writes:

With that stigma in mind [that there is an inverse relationship between “intelligence” and athletic performance], perhaps the most important writing Cooper did in Black Superman was his methodological evisceration of any supposed inverse link between physical and mental prowess. “The concept that physical superiority could somehow be a symptom of intellectual superiority became associated with African Americans … That association did not begin until about 1936.”

What Cooper (2004) implied is that there was no “inverse relationship” with intelligence and athletic ability until Jesse Owens blew away the competition at the 1936 Olympics in Berlin, Germany. In fact, the relationship between “intelligence” and athletic ability is positive (Heppe et al, 2016). Cooper is also a co-author of a paper Some Bio-Medical Mechanisms in Athletic Prowess with Morrison (Morrison and Cooper, 2006) where they argue—convincingly—that the “mutation appears to have triggered a series of physiological adjustments, which have had favourable athletic consequences.”

Thus, the hypothesis claims that differences in glucose conversion rates between West African blacks and her descendants began, but did not end with the sickling of the hemoglobin molecule, where valine is substituted for glutamic acid, which is the sixth amino acid of the beta chain of the hemoglobin molecule. Marlin et al (2007: 624) showed that male athletes who were inflicted with the sickle cell trait (SCT) “are able to perform sprints and brief exercises at the highest levels.” This is more evidence for Morrison and Cooper’s (2006) hypothesis on the evolution of muscle fiber typing in West African blacks.

Bejan, Jones, and Charles (2010) explain that the phenomenon of whites being faster swimmers in comparison to blacks being faster runners can be accounted for by physics. Since locomotion is a “falling-forward cycle“, body mass falls forward and then rises again, so mass that falls from a higher altitude falls faster and forward. The altitude is set by the position of center of mass above the ground for running, while for swimming it is set by the body rising out of the water. Blacks have a center of gravity that is about 3 percent higher than whites, which implies that blacks have a 1.5 percent speed advantage in running whereas whites have a 1.5 percent speed advantage in swimming. In the case of Asians, when all races were matched for height, Asians fared even better, than whites in swimming, but they do not set world records because they are not as tall as whites (Bejan, Jones, and Charles, 2010).

It has been proposed that stereotype threat is part of the reasons for East African running success (Baker and Horton, 2003). They state that many theories have been proposed to explain black African running success—from genetic theories to environmental determinism (the notion that physiologic adaptations to climate, too, drive differences in sporting competition). Baker and Horton (2003) note that “that young athletes have internalised these stereotypes and are choosing sport participation accordingly. He speculates that this is the reason why white running times in certain events have actually decreased over the past few years; whites are opting out of some sports based on perceived genetic inferiority.” While this may be true, this wouldn’t matter, as people gravitate toward what they are naturally good at—and what dictates that is their mind, anatomy, and physiology. They pretty much argue that stereotype threat is a cause of East African running performance on the basis of two assertions: (1) that East African runners are so good that it’s pointless to attempt to win if you are not East African and (2) since East Africans are so good, fewer people will try out and will continue the illusion that East Africans would dominate in middle- and long-distance running. However, while this view is plausible, there is little data to back the arguments.

To explain African running success, we must do it through a systems view—not one of reductionism (i.e., gene-finding). We need to see how the systems in question interact with every part. So while Jamaicans, Kenyans, and Ethiopians (and American blacks) do dominate in running competitions, attempting to “find genes” that account for success n these sports seems like a moot point—since the whole system is what matters, not what we can reduce the system in question to.

However, there are some competitions that blacks do not do so well in, and it is hardly discussed—if at all—by any author that I have read on this matter. Blacks are highly under-represented in strength sports and strongman competitions. Why? My explanation is simple: the causes for their superiority in sprinting and distance running (along with what makes them successful at baseball, football, and basketball) impedes them from doing well in strength and strongman competitions. It’s worth noting that no black man has ever won the World’s Strongest Man competition (indeed the only African country to even place—Rhodesia—was won by a white man) and the causes for these disparities come down to racial differences in anatomy and physiology.

I discussed racial differences in the big four lifts and how racial differences in anatomy and physiology would contribute to how well said race performed on the lift in question. I concluded that Europeans and Asians had more of an advantage over blacks in these lifts, and the reasons were due to inherent differences in anatomy and physiology. One major cause is also the differing muscle fiber typing distribution between the races (Alma et al, 1986; Tanner et al, 2002; Caesar and Henry, 2015 while blacks’ fiber typing helps them in short-distance sprinting (Zierath and Hawley, 2003). Muscle fiber typing is a huge cause of black athletic dominance (and non-dominance). Blacks are not stronger than whites, contrary to popular belief.

I also argued that Neanderthals were stronger than Homo sapiens, which then had implications for racial differences in strength (and sports). Neanderthals had a wider pelvis than our species since they evolved in colder climes (at the time) (Gruss and Schmidt, 2016). With a wider pelvis and shorter body than Homo sapiens, they were able to generate more power. I then implied that the current differences in strength and running we see between blacks and whites can be used for Neanderthals and Homo sapiens, thusly, evolution in differing climates lead to differences in somatotype, which eventually then lead to differences in sporting competition (what Baker and Horton, 2003 term “environmental determinism” which I will discuss in the context of racial differences in sports in the future).

Finally, blacks dominate the sport of bodybuilding, with Phil Heath dominating the competition for the past 7 years. Blacks dominate bodybuilding because, as noted above, blacks have thinner skin folds than whites, so their striations in their muscles would be more prevalent, on average, at the same exact %BF. Bodybuilders and weightlifters were similar in mesomorphy, but the bodybuilders showed more musculature than the bodybuilders whereas the weightlifters showed higher levels of body fat with a significant difference observed between bodybuilders and weightlifters in regard to endomorphy and ectomorphy (weightlifters skewing endo, bodybuilders skewing ecto, as I have argued in the past; Imran et al, 2011).

To conclude, blacks do dominate American sporting competition, and while much ink has been spilled arguing that cultural and social—not genetic or biologic—factors can explain black athletic superiority, they clearly work in concert with a strong mind to produce the athletic phenotype, no one factor has prominence over the other; though, above all, if one does not have the right mindset for the sport in question, they will not succeed. A complex array of factors is the cause of black athletic dominance, including muscle fibers, the type of mindset, anatomy, overall physiology and fat mass (among other variables) explain the hows and whys of black athletic superiority. Cultural and social explanations—on their own—do not tell the whole story, just as genetic/biologic explanations on their own would not either. Every aspect—including the historical—needs to be looked at when discussing the dominance (or lack thereof) in certain sports along with genetic and nongenetic factors to see how and why certain races and ethnies excel in certain sports.

Twin Studies, Adoption Studies, and Fallacious Reasoning

2350 words

Twin and adoption studies have been used for decades on the basis that genetic and environmental causes of traits and their variation in the population could be easily partitioned by two ways: one way is to adopt twins into separate environments, the other to study reared-together or reared-apart twins. Both methods rest on a large number of (invalid) assumptions. These assumptions are highly flawed and there is no evidential basis to believe these assumptions, since the assumptions have been violated which invalidates said assumptions.

Plomin et al write (2013) write: For nearly a century, twin and adoption studies have yielded substantial estimates of heritability for cognitive abilities.

But the validity of the “substantial estimates of heritability for cognitive abilities” is strongly questioned due to unverified (and false) assumptions that these researchers make.

Adoption studies

The problem with adoption studies are numerous, not least: restricted range of adoptive families; selective placement; late separation; parent-child attachment disturbance; problems with the tests (on personality, ‘IQ’); the non-representativeness of adoptees compared to non-adoptees; and the reliability of the characteristic in question.

In selective placement, the authorities attempt to place children in homes close to their biological parents. They gage how “intelligent” they believe they are (on the basis of parental SES and the child’s parent’s perceived ‘intelligence’), thusly this is a pretty huge confound for adoption studies.

According to adoption researcher Harry Munsinger, a “possible source of bias in adoption studies is selective placement of adopted children in adopting homes that are similar to their biological parents’ social and educational backgrounds.” He recognized that “‘fitting the home to the child’ has been the standard practice in most adoption agencies, and this selective placement can confound genetic endowment with environmental influence to invalidate the basic logic of an adoptive study (Munsinger, 1975, p. 627). Clearly, agency policies of “fitting the home to the child” are a far cry from random placement of adoptees into a wide range of adoptive homes. (Joseph, 2015: 30-1)

Richardson and Norgate (2005) argue that simple additive effects for both genetic and environmental effects are false; that IQ is not a quantitative trait; while other interactive effects could explain the IQ correlation.

1) Assignment is nonrandom. 2) They look for adoptive homes that reflect the social class of the biological mother. 3) This range restriction reduces the correlation estimates between adopted children and adopted parents. 4) Adoptive mothers come from a narrow social class. 5) Their average age at testing will be closet to their biological parents than adopted parents. 6) They experience the womb of their mothers. 7) Stress in the womb can alter gene expression. 8) Adoptive parents are given information about the birth family which may bias their treatment. 9) Biological mothers and adopted children show reduced self-esteem and are more vulnerable to changing environments which means they basically share environment. 10) Conscious or unconscious aspects of family treatment may make adopted children different from other adopted family members. 11) Adopted children also look more like their biological parents than their adoptive parents which means they’ll be treated accordingly.

Twin studies

Personally, my favorite thing to discuss. Twin studies rest on the erroneous assumption that DZ and MZ environments are equal; that they get treated equally the same. This is false, MZ twins get treated more similarly than DZ twins, which twin researchers have conceded decades ago. But in order to save their field, they attempt to use circular argumentation, known as Argument A. Argument A states that MZTs (monozygotic twins reared together) are more genetically similar than DZTs (dizygotic twins reared together) and thusly this causes greater behavioral similarity. But this is based on circular reasoning: the researchers already implicitly assumed that genes played a role in their premise and, not surprisingly, in their conclusion genes are the cause for the similarities of the MZTs. So Argument A is used, twin researchers circularly assume that MZTs greater behavioral similarity is due to genetic similarity, while their argument that genetic factors explain the greater behavioral similarity of MZTs is a premise and conclusion of their argument. “X is true because Y is true; Y is true because X is true.” (Also see Joseph et al, 2015.)

We have seen that circular reasoning is “empty reasoning in which the conclusion rests on an assumption whose validity is dependent on the conclusion” (Reber, 1985, p. 123). … A circular argument consists of “using as evidence a fact which is authenticated by the very conclusion it supports,” which “gives us two unknowns so busy chasing each other’s tails that neither has time to attach itself to reality” (Pirie, 2006, p. 27) (Joseph, 2016: 164).

Even if Argument A is accepted, the causes of behavioral similarities between MZ/DZ twins could still come down to environment. Think of any type of condition that is environmentally caused but is due to people liking what causes the condition. There are no “genes for” that condition, but their liking the thing that caused the condition caused an environmental difference.

Argument B also exists. Those that use Argument B also concede that MZs experience more similar environments, but then argue that in order to show that twin studies, and the EEA, are false, critics must show that MZT and DZT environments differ in the aspects that are relevant to the behavior in question (IQ, schizophrenia, etc).

An example of an Argument B environmental factor relevant to a characteristic or disorder is the relationship between exposure to trauma and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Because trauma exposure is (by definition) an environmental factor known to contribute to the development of PTSD, a finding that MZT pairs are more similarly exposed to trauma than DZT pairs means that MZT pairs experience more similar “trait-relevant” environments than DZTs. Many twin researchers using Argument B would conclude that the EEA is violated in this case. (Joseph, 2016: 165)

So twin researchers need to rule out and identify “trait-relevant factors” which contribute to the cause of said trait, along with experiencing more similar environments, invalidates genetic interpretations made using Argument B. But Argument A renders Argument B irrelevant because even if critics can show that MZTs experience more similar “trait-relevant environments”, they could still argue that the twin method is valid by stating that (in Argument A fashion) MZTs create and elicit more similar trait-relevant environments.

One more problem with Argument A is that it shows that twins behave accordingly to “inherited environment-creating blueprint” (Joseph, 2016: 164) but at the same time shows that parents and other adults are easily able to change their behaviors to match that of the behaviors that the twins show, which in effect, allows them to “create” or “elicit” their own environments. But the adults’ “environment-creating behavior and personality” should be way more unchangeable than the twins’ since along with the presumed genetic similarity, adults have “experienced decades of behavior-molding peer, family, religious, and other socialization influences” (Joseph, 2016: 165).

Whether or not circular arguments are “useful” or not has been debated in the philosophical literature for some time (Hahn, Oaksford, and Corner, 2005). However, assuming, in your premise, that your conclusion is valid is circular and therefore While circular arguments are deductively valid, “it falls short of the ultimate goal of argumentative discourse: Whatever evaluation is attached to the premise is transmitted to the conclusion, where it remains the same; no increase in degree of belief takes place” (Hahn, 2011: 173).

However, Hahn (2011: 180) concludes that “the existence of benign circularities makes clear that merely labeling something as circular is not enough to dismiss it; an argument for why the thing in question is bad still needs to be made.” This can be simply shown: The premise that twin researchers use (that genes cause similar environments to be constructed) is in their conclusion. They state in their premise that MZT behavioral similarity is due to greater MZT genetic similarity in comparison to DZTs (100 vs. 50 percent). Then, in the conclusion, they re-state that the behavioral similarities of MZTs is due to their genetic similarity compared to DZTs (100 vs. 50 percent). Thus, a convincing argument for conclusion C (that genetic similarity explains MZT behavioral similarity) cannot rest on the assumption that conclusion C is correct. Thus, Argument A is fallacious due to its circularity.

What causes MZT behavioral similarities is their more similar environment: they get treated the same by peers and parents, and have higher rates of identity confusion and had a closer emotional bond compared to DZTs. The twin method is based on the (erroneous) assumption that MZT and DZT pairs experience roughly equal environments, which twin researchers conceded was false decades ago.

Richardson and Norgate (2005: 347) conclude (emphasis mine):

We have shown, first, that the EEA may not hold, and that well-demonstrated treatment effects can, therefore, explain part of the classic MZ–DZ differences. Using published correlations, we have also shown how sociocognitive interactions, in which DZ twins strive for a relative ‘apartness’, could further depress DZ correlations, thereby possibly explaining another part of the differences. We conclude that further conclusions about genetic or environmental sources of variance from MZ–DZ twin data should include thorough attempts to validate the EEA with the hope that these interactions and their implications will be more thoroughly understood.

Of course, even if twin studies were valid and the EEA was true/ the auxiliary arguments used were true, this would still not mean that heritability estimates would be of any use to humans, since we cannot control environments as we do in animal breeding studies (Schonemann, 1997; Moore and Shenk, 2016). I have chronicled how 1) the EEA is false and how flawed twin studies are; 2) how flawed heritability estimates are; 3) how heritability does not (and cannot) show causation; and 4) the genetic reductionist model that behavioral geneticists rely on is flawed (Lerner and Overton, 2017).

So we can (1) accept the EEA, that the greater behavioral resemblance indicates the importance of genetic factors underlying most human behavioral differences and behavioral disorders or we can (2) reject the EEA and state that the greater behavioral resemblance is due to nongenetic (environmental) factors, which means that all genetic interpretations of MZT/DZT studies must be rejected. Thus, using (2), we can infer that all twin studies measure is similarity of the environment of DZTs, and it is, in fact, not measuring genetic factors. Accepting explanation 2 does not mean that “twin studies overestimate heritability, or that researchers should assess the EEA on a study-by-study basis, but instead indicates that the twin method is no more able than a family study to disentangle the potential influences of genes and environment” (Joseph, 2016: 181).

What it does mean, however, is that we can, logically, discard all past, future, and present MZT and DZT comparisons and these genetic interpretations must be outright rejected, due to the falsity of the EEA and the fallaciousness of the auxiliary arguments made in order to save the EEA and the twin method overall.

There are further problems with twin studies and heritability estimates. Epigenetic supersimilarity (ESS) also confounds the relationship. Due to the existence of ESS “human MZ twins clearly cannot be viewed as the epigenetic equivalent of isogenic inbred mice, which originate from separate zygotes. To the extent that epigenetic variation at ESS loci influences human phenotype, as our data indicate, the existence of ESS establishes a link between early embryonic epigenetic development and adult disease and may call into question heritability estimates based on twin studies” (Van Baak et al, 2018). In other words, ESS is an unrecognized phenomenon that contributes to the phenotypic similarity of MZs, which calls into question the usefulness of heritability studies using twins. The uterine environment has been noted to be a confound by numerous authors (Devlin, Daniels, and Roeder, 1997; Charney, 2012; Ho, 2013; Moore and Shenk, 2016).

Conclusion

Adoption studies fall prey to numerous pitfalls, most importantly, that children are adopted into similar homes compared to their birth parents, which restricts the range of environments for adoptees. Adoption placement is also non-random, the children are placed into homes that are similar to their biological parents. Due to these confounds (and a whole slew of other invalidating problems), adoption studies cannot be said to show genetic causation, nor can they separate genetic from environmental factors.

Twin studies suffer from the biggest flaw of all: the falsity of the EEA. Since the EEA is false—which has been recognized by both critics and supporters of the assumption—the supporters of the assumption have attempted to redefine the EEA in two ways: (1) that MZTs experience more similar environments due to genetic similarity (Argument A) and (2) that it is not whether MZTs experience more similar environments, but whether or not they share more similar trait-relevant environments. Thus, unless these twin researchers are able to identify trait-relevant factors that contribute to the trait in question, we must conclude that (along with the admission from twin researchers that the EEA is false; that MZTs experience more similar environments than DZTs) genetic interpretations made using Argument B are thusly invalidated. Fallacious reasoning (“X causes Y; Y causes X) does not help any twin argument. Because their conclusion is already implicitly assumed in their premise.

The existence of ESS (epigenetic supersimilarity) further shows how invalid the twin method truly is, because the confounding starts in the womb. Attempts can be made (however bad) to control for shared environment by adopting different twins into different homes, but they still shared a uterine environment which means they shared an environment, which means it is a confound and it cannot be controlled for (Charney, 2012).

Adoption and twin studies are highly flawed. Like family studies, twin studies are no more able to disentangle genetic from environmental effects than a family study, and thus twin studies cannot separate genes from environment. Last, and surely not least, it is fallacious to assume that genes can be separated so neatly into “heritability estimates” as I have noted in the past. Heritability estimates cannot show genetic causation, nor can it show how malleable a trait is. They’re just (due to how we measure) flawed measures that we cannot fully control so we must make a number of (false) assumptions that then invalidate the whole paradigm. The EEA is false, all auxiliary arguments made to save the EEA are fallacious; adoption studies are hugely confounded; twin studies are confounded due to numerous reasons, most importantly the uterine environment (Van Baak et al, 2018).

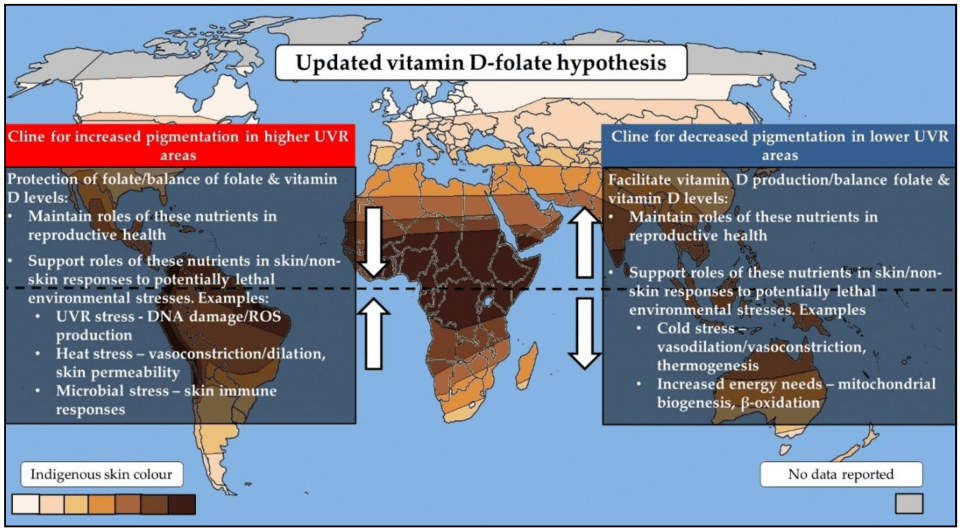

Nina Jablonski on Race

1550 words

Nina Jablonski’s work on vitamin D and the implications that lighter skin had not only on our evolution but our health are extremely important for understanding how we evolved after the out of Africa migration. However, Jablonski then takes what she has written about skin color over the past few decades and concludes that race doesn’t exist. Jablonski believes that the term “race” should be discontinued from our lexicon, but as most may know, the term “race” does not need to disappear from our lexicon. (Watch her TED Talk Skin Color is an Illusion.)

In 2014, Nina Jablonski stated that the term “race” was ready for scientific retirement. In the article—and her book (Jablonski, 2012: chapters 9 and 10)—she states that race was a “vague and slippery concept”, eschewing the views of Kant and Hume as “racist”. She talks about how Kant was really one of the first people to recognize and categorize groups of people as “races”, stating that skin color, hair type, skull type etc—along with differing mores, aptitudes, and capacity for civilization—arranged in a hierarchical manner with Europeans at the top. A climatic theory was held, which stated that the original humans were light and became darker since “the transformation from light to dark was a form of degeneration, a departure from the norm” (Jablonski, 2012: 143).

She then discusses how, in Biblical history, skin color was meaningful, meaningful because it was believed that darker-skinned races were descendants of Ham:

And the sons of Noah, that went forth of the ark, were Shem, and Ham, and Japheth: and Ham is the father of Canaan. These are the three sons of Noah: and of them was the whole earth overspread. And Noah began to be an husbandman, and he planted a vineyard: And he drank of the wine, and was drunken; and he was uncovered within his tent. And Ham, the father of Canaan, saw the nakedness of his father, and told his two brethren without. And Shem and Japheth took a garment, and laid it upon both their shoulders, and went backward, and covered the nakedness of their father; and their faces were backward, and they saw not their father’s nakedness. And Noah awoke from his wine, and knew what his younger son had done unto him. And he said, Cursed be Canaan; a servant of servants shall he be unto his brethren. And he said, Blessed be the Lord God of Shem; and Canaan shall be his servant. (Genesis, 9: 18-26)

So Noah’s three sons—Ham, Japheth and Shem—were seen to be the three modern-day races of man—Africans, Europeans, and Asians, respectively. The term “servant of servants” was taken to mean that the descendants of Ham would serve the descendants of Shem and Japheth. This, according to those who believed the authority of the Bible, was enough to justify chattel slavery.

Jablonski—in an interview with the magazine Nautilus—stated that there “are no clean breaks between human populations. Individuals have different groups of genes” and that “Only a tiny fraction of alleles, and a small fraction of allelic combinations, is restricted to a single geographic region, and even less to a single population” which “is why attempts to identify races in humans have failed.” She commits the continuum fallacy, and the argument form is thus: “One extreme is X, at another is Y. There is no definable point where X becomes Y. Therefore, there is no difference between X and Y.” This has also been called the “Argument of the Beard”: at what point does a man not become clean shaven?

The use of the continuum fallacy, that there “are no clean breaks between human populations” shows how far the “race is a social construct” line has come (it is, but that race is a social construct does not also mean that it cannot also be a significant biological reality). The continuum fallacy is one of the most-used fallacies by those who deny race. Though, those who use the continuum fallacy are only attempting to argue that the claim is “too vague” because it is not as precise as they would like it to be. It does not matter that there “are no clean breaks between human populations“; what matters is that patterns of visible physical features correspond to geographic ancestry, and this is what we find.

Her second problem arises when she says that “Only a tiny fraction of alleles, and a small fraction od allelic combinations, is restricted to a single geographic region, and even less to s single population“. That there are no “race genes” or “genes for race” does not mean that race does not exist as a biological reality; these rigid “either this or that” definitions that some people have for race, such as race-specific genes are strawmen: people who believe that race is a significant biological reality do not believe in race-specific genes. That there are no race-specific genes does not mean that race doesn’t exist, as we know that genes are expressed differently in different races.

Finally, she claims that this “is why attempts to identify races in humans have failed“, though these attempts have not failed, of course. So-called races are distinguished by patterns of visible physical features; these patterns are observed between real, existing groups; these real existing groups that share these patterns of visible physical features satisfy the requisites of minimalist race; therefore race exists. Of course, Jablonski has reservations about acknowledging the reality of race due to how the transatlantic slave trade was promogulated through so-called differences that stemmed from Noah and Ham’s curse, but I fail to see why she would discard the argument just provided for the existence of race since differences in mores, intelligence, physical and mental abilities, are not discussed in the argument. ONLY the observable differences between populations are observed, with no value-judgment put onto each race, such as having lower “intelligence” or differing mores compared to another race.