Home » Posts tagged 'Race Realism' (Page 4)

Tag Archives: Race Realism

Testosterone and Aggressive Behavior

1200 words

Testosterone gets a bad rep. People assume that if one has higher testosterone than average, that they will be a savage, bloodthirsty beast with an insatiable thirst for blood. This, however, is not the case. I’ve documented how testosterone is vital for male functioning, and how higher levels don’t lead to maladies such as prostate cancer. Testosterone is feared for no reason at all. The reason that people are scared of it is that of the anecdotal reports that individual A had higher testosterone when he committed crime B so, therefore, anyone who commits a crime has higher testosterone and that is the ultimate—not proximate—cause of crime. This is erroneous. There is a positive—albeit extremely low—correlation between physical aggression and violence at .14. That’s it. Furthermore, most of these claims of higher levels of testosterone causing violence is extrapolated from animal studies to humans.

Testosterone has been shown to lead to violent and aggressive behavior, largely only in animal studies (Archer, 1991; Book et al, 2001). For years, the relationship between the two variables was thought to be causal, i.e., high levels of testosterone cause violent crimes, which has been called into question over recent years. This is due to how the environment can raise testosterone levels. I have documented how these environmental factors can raise testosterone—and after these events, testosterone stays elevated.

Largely, animal studies are used to infer that high levels of testosterone in and of themselves lead to higher rates of aggression and therefore crime. However, two important meta-analyses show this is not necessarily the case (Archer, 1991; Book et al, 2001). Book et al, 2001 showed that two variables were important in seeing the relationship between aggression and crime—the time of day that the assay was taken and the age of the participant. This effect was seen to be largest in, not unexpectedly, males aged 13-20 (Book et al, 2001: 594). So since age confounds the relationship between aggression and testosterone in males, that is a variable that must also be controlled for (which, in the meta-analyses and other papers I cite on black and white testosterone is controlled for).

More interestingly, Book et al (2001) showed that the nature of the measure of aggression (self-reported or behavioral) did not have any effect on the relationship between testosterone and aggression. Since there is no difference between the two measures, then a pencil-and-paper test is a good enough index of measure of aggression, comparable to observing the behavior of the individual studied.

Archer (1991) also showed the same low—but positive—correlations between aggression and testosterone. Of course, as I’ve extensively documented since there is a positive relationship between the two variables does not necessarily mean that high-testosterone men commit more crime—since the outcome of certain situations can increase and decrease testosterone, no causal factors have been detangled. Book et al (2001) confirmed Archer’s (1991) finding that the correlation between violent and aggressive behavior was positive and low at .14.

Valois et al (2017) showed there was a relationship between emotional self-efficacy (ESE) and aggressive and violent behaviors in a statewide sample of high school children in South Carolina (n=3,386). Their results suggested that there was a relationship between carrying a weapon to school within the past 30 days along with being injured with a club, knife or gun in the past 12 months was significantly associated with ESE for specific race and sex groups.

Black girls who reported a low ESE reported carrying a weapon to school 30 days prior to the survey were 3.22 times more than black girls with a high ESE who did not report carrying a weapon to school within the past 30 days prior to the questionnaire. For black boys with low ESE, they were 3.07 times more likely to carry a weapon to school within the past 30 days in comparison to black boys with high ESE who did not carry a weapon to school in the past 30 days. White girls who reported low ESE had the highest chance of bringing a weapon to school in comparison to white girls with low ESE—they were 5.87 times more likely to carry a weapon to school 30 days prior to the survey. Finally, white boys with low ESE were slightly more than 2 times more likely than white boys with high ESE to carry a weapon to school 30 days prior to the survey.

Low ESE in white and black girls is associated with carrying a weapon to school, whereas low ESE for white and black boys is associated with being threatened. Further, their results suggested that carrying a weapon to school was associated with low ESE in black and white girls suggesting that low ESE is both situation-specific and specific to the female sex. The mediator between these things is low ESE—it is different for both black boys and black girls, and when it occurs different courses of action are taken, whether it’s through bringing a weapon to school or being threatened. What this tells me is that black and white boys with low ESE are more likely to be threatened because they are perceived to be more meek, while black and white girls with low ESE that get provoked at school are more likely to bring weapons. So it seems that girls bring weapons when provoked and boys fight.

The two meta-analyses reviewed above show that there is a low positive (.14) correlation between testosterone and aggression (Archer, 1991; Book et al, 2001). Thusly, high levels of testosterone on their own are not sufficient enough to explain high levels of aggression/violence. Further, there are race- and sex-specific differences when one is threatened at high school with black and white boys being more likely to report being threatened more (which implies a higher rate of physical fighting) while black and white girls when threatened brought weapons to school. These race- and sex-specific differences in the course of action taken when they are physically threatened needs to be looked into more.

I’d like to see the difference in testosterone levels for a matched sample of black and white boys from two neighboring districts with different murder rates as a proxy for the amount of violence in the area. I’d bet that the places with a higher murder rate would have children 1) report more violence and instances of bringing weapons to school and 2) report more harm from these encounters—especially if they have low ESE as seen in Valois (2017) and 3) the children in the high schools along with the residents of the area would have higher testosterone than the place with less violence. I would expect these differences to be magnified in the direction of Valois (2017) in that areas with higher murder rates would have black and white girls report bringing weapons to school when threatened whereas black and white boys would report more physical violence.

High testosterone itself is not sufficient enough to explain violence as the correlation is extremely low at .14. Testosterone levels fluctuate depending on the time of day (Brambilla et al, 2009; Long, Nguyen, and Stevermer, 2015) to the time of year (Stanton, Mullette-Gillman, and Huettel, 2011; Demur, Uslu, and Arslun, 2016). How the genders/races react differently when threatened in adolescence is interesting and deserves further study.

Race, Testosterone, and Honor Culture

2300 words

Misinformation about testosterone and strength in regards to race is rampant in the HBD-o-sphere. One of the most oft-repeated phrases is that “Blacks have higher levels of testosterone than whites”, even after controlling for numerous confounds. However, the people who believe this literally only cite one singular study with 50 blacks and 50 whites. Looking at more robust data with higher ns shows a completely different story. Tonight I will, again, go through the race/testosterone conundrum (again).

Type I fibers fire first when heavy lifting. Whites have more type I fibers. Powerlifters and Olympic lifters have a greater amount type IIa fibers, with fewer type IIx fibers (like whites). This explains why blacks are hardly represented in powerlifting and strongman competitions.

Somatype, too, also plays a role. Whites are more endo than blacks who are more meso. Endomorphic individuals are stronger, on average, than mesomorphic and ectomorphic individuals.

Blacks have narrower hips and pelves. This morphological trait further explains why blacks dominate sports. Some people may attempt to pick out one variable that I speak about (fiber type, morphology, somatype, fat mass, etc) and attempt to disprove it, thinking that disproving that variable will discredit my whole argument. However, fiber typing is set by the second trimester, with no change in fiber type from age 6 to adulthood (Bell et al, 1980).

It is commonly believed that blacks have higher levels of testosterone than whites. However, this claim is literally based off of one study (Ross et al, 1986) when other studies have shown low to no difference in T levels (Richards et al, 1992; Gapstur et al, 2002; Rohrmann et al, 2007; Mazur, 2009; Lopez et al, 2013; Richard et al 2014). People who still push the “blacks-have-higher-T-card” in the face of this evidence are, clearly, ideologues who want to cushion their beliefs when presented with contradictory evidence (Nyhan and Reifler, 2010).

‘Honor Culture’ and testosterone

In all of my articles on this subject, I have stated—extensively—that testosterone is mediated by the environment. That is, certain social situations can increase testosterone. This is a viewpoint that I’ve emphatically stated. I came across a paper while back that talks about a sociological perspective (I have huge problems with social ‘science’, [more on that soon] but this study was very well done) in regards to the testosterone difference between blacks and whites.

Some people when they read this, however, may go immediately to the part of the paper that says what they want it to say without fully assessing the paper. In this section, I will explain the paper and how it confirms my assertions/arguments.

Mazur (2016) begins the paper talking about ‘honor culture‘, which is a culture where people avoid intentionally offending others while also maintaining a status for not backing down from a confrontation. This theory was proposed by Richard Nisbett in 1993 to explain why the South had higher rates of violence—particularly the Scotch-Irish.

However parsimonious the theory may sound, despite its outstanding explanatory power, it doesn’t hold while analyzing white male homicides in the South. It also doesn’t hold analyzing within-county homicide rates either, since apparently poverty better explains higher homicide rates.

But let’s assume it’s true for blacks. Let’s assume the contention to be true that there is an ‘honor culture’ that people take part in.

Young black men with no education had higher levels of testosterone than educated whites and blacks. Looking at this at face value—literally going right to the section of the paper that says that poor blacks had higher testosterone, nearly 100 ng/ml higher than the mean testosterone of whites. As Mazur (2016) notes, this contradicts his earlier 2009 study in which he found no difference in testosterone between the races.

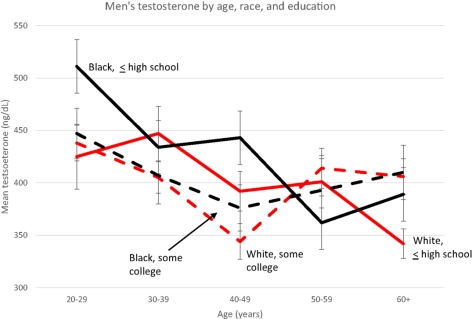

Note the low testosterone for both races at age 20-29—ranging from about 515 to 425—why such low testosterone levels for young men? Anyway, the cause for the higher levels is due to the type of honor culture that blacks participate in, according to Mazur (which is consistent with the data showing that testosterone rises during conflict/aggressive situations).

Mazur cites Elijah Anderson, saying that most youths have a “code of the streets” they take part in, which have to do with interpersonal communication such as “gait and verbal expressions” to deter aggressive behavior.

Testosterone is not a causal variable in regards to violent behavior. But it does rise during conflicts with others, watching a favorite sports team, asserting dominance, and even how you carry yourself (especially your posture). Since low-class blacks participate in these types of behaviors, then they would have higher levels of testosterone due to needing to “keep their status.”

When testosterone rises in these situations, it increases the response threat in mens’ brains, most notably showing increased activity in the amygdala. Further, dominant behavior and posture also increase testosterone levels. Putting this all together, since blacks with only a high school education have higher testosterone levels and are more likely to participate in honor culture compared to whites and blacks with higher educational achievement, then they would have higher testosterone levels than whites and blacks with a high school education who do not participate in honor culture.

Further, as contrary to what I have written in the past (and have since rescinded), there is no indication of higher testosterone levels in black women with low education. It seems this ‘honor culture’ effect on testosterone only holds for black men with only a high school education.

Mazur’s (2016) most significant finding was that black men aged 20-29 with only a high school education had 91 ng/ml higher testosterone than whites. Among older and/or educated men, testosterone did not vary. This indicates that since they have attained higher levels of educational success, there is no need to participate in ‘honor culture’.

This is yet further evidence for my assertion that environmental variables such as posture, dominance, and aggressive behavior raise testosterone levels.

The honor culture hypothesis is found to hold in Brazil in a comparative study of 160 inmates and non-inmates (De Souza et al, 2016). As Mazur (2016) notes, the honor culture hypothesis could explain the high murder rate for black Americans—the need to ‘keep their status’. It’s important to note that this increase in testosterone was not noticed in teenage or female blacks (because they don’t participate in honor culture).

There is a perfectly good environmental—not genetic—reason for this increase in testosterone in young blacks with only a high school education. Now that we know this, back to race and strength.

Mazur (2009) found that black men in the age range of 20-69, they averaged .39 ng/ml higher testosterone than whites, which is partly explained by lower marriage rates and low adiposity. White men are more likely to be obese than black men, since black men with more African ancestry are less likely to be obese. When controlling for BMI, blacks are found to have 2.5-4.9 percent more testosterone than whites (Gapstur et al, 2002, Rohrmann et al, 2007, Richard et al, 2014). There is little evidence for the assertion that blacks have higher levels of testosterone without environmental triggers.

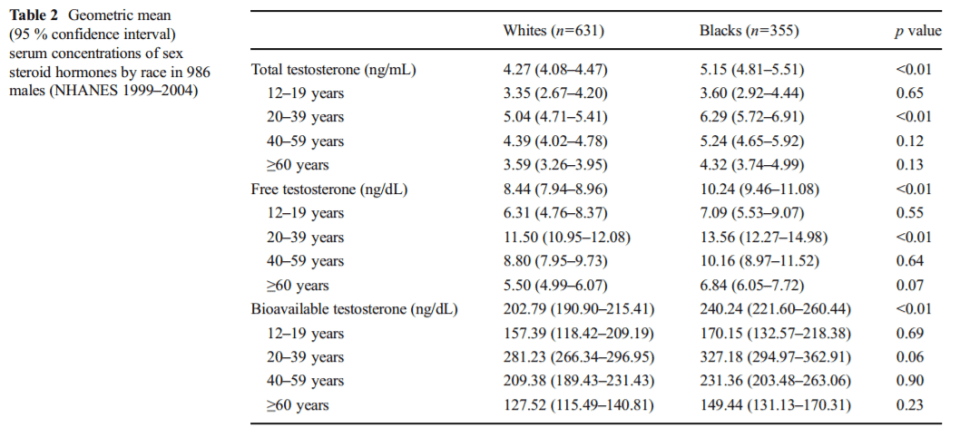

Blacks between the age of 12 and 15 average lower levels of testosterone than whites. However, after the age of 15, “testosterone levels increase rapidly” with blacks having higher peak levels than whites (seen in table 2 below). After adjusting for the usual confounds (BMI, smoking, age, physical activity, and waist circumference), blacks still had higher levels of testosterone—which is attributed to higher levels of lean mass.

As seen above in table 2 from Hu et al (2014), the difference in total testosterone between blacks and whites aged 20-39 was 6.29 ng/ml and 5.04 ng/ml respectively, with free testosterone for whites being 11.50 and 13.56 for blacks and finally bioavailable testosterone for whites and blacks aged 20-39 was 281.23 and 327.18 ng/ml respectively. These small differences in testosterone cannot account for racial disparities in violence nor prostate cancer—since there is no relationship between prostate cancer and testosterone (Stattin et al, 2003; Michaud, Billups, and Partin, 2015).

In regards to Africans, the best studies I can find comparing some African countries with the West study salivary testosterone. However, there is a direct correlation between salivary testosterone and free serum testosterone (Wang et al, 1981; Johnson, Joplin, and Burrin, 1987). Of the studies I could find, Kenyan pastoralists called the Ariaal have lower levels of testosterone than Western men (Campbell, O’Rourke, and Lipson, 2003; Campbell, Gray, and Ellison, 2006) while men in Zimbabwe had levels “much lower” compared to Western populations (Lukas, Campbell, and Ellison, 2004). Lastly, among men aged 15 to 30, salivary testosterone levels in an American sample was 335 pmol//l compared to 286 pmol/l in men from the Congo (Elisson et al, 2002). Even certain African populations don’t have higher testosterone levels than Western peoples.

Conclusion

The meme that blacks have higher rates of testosterone in comparison to whites needs to be put to rest. This is only seen in blacks who participate in ‘honor culture’, which is an environmental variable. This is in contrast to people who believe that it is genetic in nature—environmental variables can and do drive hormones. Mazur (2016) is proof of that. Mazur (2016) also shows that the honor culture hypothesis doesn’t hold for teens or black males—so they don’t have elevated levels of testosterone. Certain studies of African populations, however, do not show higher levels of testosterone than Western populations.

Looking at the complete literature—rather than a select few studies— we can see that testosterone levels between white and black Americans are not as high as is commonly stated (Richards et al, 1992; Gapstur et al, 2002; Rohrmann et al, 2007; Mazur, 2009; Lopez et al, 2013; Hu et al, 2014; Richard et al, 2014). Further, even if blacks did have higher levels of testosterone than whites—across the board (sans honor culture), it still wouldn’t explain higher rates of black violence when compared to whites, nor would it explain higher prostate cancer rates (Stattin et al, 2003; Michaud, Billups, and Partin, 2015).

Only blacks with low educational achievement have higher levels of testosterone—which, even then is not enough to explain higher rates of violence or prostate cancer acquisition. Other factors explain the higher murder rate (i.e., honor culture, which increases testosterone, the environmental trigger matters first and foremost) and violent crime that blacks commit. But attempting to explain it with 30-year-old studies (Ross et al, 1986) and studies that show that environmental factors increase testosterone (Mazur, 2016) don’t lend credence to that hypothesis.

References

Bell, R. D., Macdougall, J. D., Billeter, R., & Howald, H. (1980). Muscle fiber types and morphometric analysis of skeletal muscle in six-year-old children. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise,12(1). doi:10.1249/00005768-198021000-00007

Campbell, B., O’rourke, M. T., & Lipson, S. F. (2003). Salivary testosterone and body composition among Ariaal males. American Journal of Human Biology,15(5), 697-708. doi:10.1002/ajhb.10203

Campbell, B. C., Gray, P. B., & Ellison, P. T. (2006). Age-related patterns of body composition and salivary testosterone among Ariaal men of Northern Kenya. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research,18(6), 470-476. doi:10.1007/bf03324846

De Souza, Souza, B. C., Bilsky, W., & Roazzi, A. (2016). The culture of honor as the best explanation for the high rates of criminal homicide in Pernambuco: A comparative study with 160 convicts and non-convicts. Anuario de Psicología Jurídica,26(1), 114-121. doi:10.1016/j.apj.2015.03.001

Ellison, P. T., Bribiescas, R. G., Bentley, G. R., Campbell, B. C., Lipson, S. F., Panter-Brick, C., & Hill, K. (2002). Population variation in age-related decline in male salivary testosterone. Human Reproduction,17(12), 3251-3253. doi:10.1093/humrep/17.12.3251

, , , , , . Serum androgen concentrations in young men: a longitudinal analysis of associations with age, obesity, and race—the CARDIA male hormone study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2002; 11: 1041–7

Hu, H., Odedina, F. T., Reams, R. R., Lissaker, C. T., & Xu, X. (2014). Racial Differences in Age-Related Variations of Testosterone Levels Among US Males: Potential Implications for Prostate Cancer and Personalized Medication. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities,2(1), 69-76. doi:10.1007/s40615-014-0049-8

Johnson, S. G., Joplin, G. F., & Burrin, J. M. (1987). Direct assay for testosterone in saliva: Relationship with a direct serum free testosterone assay. Clinica Chimica Acta,163(3), 309-318. doi:10.1016/0009-8981(87)90249-x

Lopez, D. S., Peskoe, S. B., Joshu, C. E., Dobs, A., Feinleib, M., Kanarek, N., . . . Platz, E. A. (2013). Racial/ethnic differences in serum sex steroid hormone concentrations in US adolescent males. Cancer Causes & Control,24(4), 817-826. doi:10.1007/s10552-013-0154-8

Lukas, W. D., Campbell, B. C., & Ellison, P. T. (2004). Testosterone, aging, and body composition in men from Harare, Zimbabwe. American Journal of Human Biology,16(6), 704-712. doi:10.1002/ajhb.20083

Mazur, A. (2009). The age-testosterone relationship in black, white, and Mexican-American men, and reasons for ethnic differences. The Aging Male,12(2-3), 66-76. doi:10.1080/13685530903071802

Mazur, A. (2016). Testosterone Is High among Young Black Men with Little Education. Frontiers in Sociology,1. doi:10.3389/fsoc.2016.00001

Michaud, J. E., Billups, K. L., & Partin, A. W. (2015). Testosterone and prostate cancer: an evidence-based review of pathogenesis and oncologic risk. Therapeutic Advances in Urology,7(6), 378-387. doi:10.1177/1756287215597633

Nyhan, B., & Reifler, J. (2010). When Corrections Fail: The Persistence of Political Misperceptions. Political Behavior,32(2), 303-330. doi:10.1007/s11109-010-9112-2

Richard, A., Rohrmann, S., Zhang, L., Eichholzer, M., Basaria, S., Selvin, E., . . . Platz, E. A. (2014). Racial variation in sex steroid hormone concentration in black and white men: a meta-analysis. Andrology,2(3), 428-435. doi:10.1111/j.2047-2927.2014.00206.x

Richards, R. J., Svec, F., Bao, W., Srinivasan, S. R., & Berenson, G. S. (1992). Steroid hormones during puberty: racial (black-white) differences in androstenedione and estradiol–the Bogalusa Heart Study. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism,75(2), 624-631. doi:10.1210/jcem.75.2.1639961

Rohrmann, S., Nelson, W. G., Rifai, N., Brown, T. R., Dobs, A., Kanarek, N., . . . Platz, E. A. (2007). Serum Estrogen, But Not Testosterone, Levels Differ between Black and White Men in a Nationally Representative Sample of Americans. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism,92(7), 2519-2525. doi:10.1210/jc.2007-0028

Ross R, Bernstein L, Judd H, Hanisch R, Pike M, Henderson B. Serum testosterone levels in healthy young black and white men. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1986 Jan;76(1):45–48

Stattin, P., Lumme, S., Tenkanen, L., Alfthan, H., Jellum, E., Hallmans, G., . . . Hakama, M. (2003). High levels of circulating testosterone are not associated with increased prostate cancer risk: A pooled prospective study. International Journal of Cancer,108(3), 418-424. doi:10.1002/ijc.11572

Wang, C., Plymate, S., Nieschlag, E., & Paulsen, C. A. (1981). Salivary Testosterone in Men: Further Evidence of a Direct Correlation with Free Serum Testosterone. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism,53(5), 1021-1024. doi:10.1210/jcem-53-5-1021

The Evolution of Human Skin Variation

4050 words

Human skin variation comes down to how much UV radiation a population is exposed to. Over time, this leads to changes in genetic expression. If that new genotype is advantageous in that environment, it will get selected for. To see how human skin variation evolved, we must first look to chimpanzees since they are our closest relative.

The evolution of black skin

Humans and chimps diverged around 6-12 mya. Since we share 99.8 percent of our genome with them, it’s safe to say that when we diverged, we had pale skin and a lot of fur on our bodies (Jablonski and Chaplin, 2000). After we lost the fur on our bodies, we were better able to thermoregulate, which then primed Erectus for running (Liberman, 2015). The advent of fur loss coincides with the appearance of sweat glands in Erectus, which would have been paramount for persistence hunting in the African savanna 1.9 mya, when a modern pelvis—and most likely a modern gluteus maximus—emerged in the fossil record (Lieberman et al, 2006). This sets the stage for one of the most important factors in regards to the ability to persistence hunt—mainly, the evolution of dark skin to protect against high amounts of UV radiation.

After Erectus lost his fur, the unforgiving UV radiation beamed down on him. Selection would have then occurred for darker skin, as darker skin protects against UV radiation. Dark skin in our genus also evolved between 1 and 2 mya. We know this since the melanocortin 1 receptor promoting black skin arose 1-2 mya, right around the time Erectus appeared and lost its fur (Lieberman, 2015).

However, other researchers reject Greaves’ explanation for skin cancer being a driver for skin color (Jablonksi and Chaplin, 2014). They cite Blum (1961) showing that skin cancer is acquired too late in life to have any kind of effect on reproductive success. Skin cancer rates in black Americans are low compared to white Americans in a survey from 1977-8 showing that 30 percent of blacks had basal cell carcinoma while 80 percent of whites did (Moon et al, 1987). This is some good evidence for Greaves’ hypothesis; that blacks have less of a rate of one type of skin cancer shows its adaptive benefits. Black skin evolved due to the need for protection from high levels of UVB radiation and skin cancers.

Highly melanized skin also protects against folate destruction (Jablonksi and Chaplin, 2000). As populations move away from high UV areas, the selective constraint to maintain high levels of folate by blocking high levels of UV is removed, whereas selection for less melanin prevails to allow enough radiation to synthesize vitamin D. Black skin is important near the equator to protect against folate deficiency. (Also see Nina Jablonski’s Ted Talk Skin color is an illusion.)

The evolution of white skin

The evolution of white skin, of course, is much debated as well. Theories range from sexual selection, to diet, to less UV radiation. All three have great explanatory power, and I believe that all of them did drive the evolution of white skin, but with different percentages.

The main driver of white skin is living in colder environments with fewer UV rays. The body needs to synthesize vitamin D, so the only way this would occur in areas with low UV rays.

White skin is a recent trait in humans, appearing only 8kya. A myriad of theories have been proposed to explain this, from sexual selection (Frost, 2007), which include better vitamin D synthesis to ensure more calcium for pregnancy and lactation (which would then benefit the intelligence of the babes) (Jablonski and Chaplin, 2000); others see light skin as the beginnings of more childlike traits such as smoother skin, a higher pitched voice and a more childlike face which would then facilitate less aggressiveness in men and more provisioning (Guthrie, 1970; from Frost, 2007); finally, van den Berghe and Frost (1986) proposed that selection for white skin involved unconscious selection by men for lighter-skinned women which is used “as a measure of hormonal status and thus childbearing potential” (Frost, 2007). The three aforementioned hypotheses have sexual selection for lighter skin as a proximate cause, but the ultimate cause is something completely different.

The hypothesis that white skin evolved to better facilitate vitamin D synthesis to ensure more calcium for pregnancy and lactation makes the most sense. Darker-skinned individuals have a myriad of health problems outside of their ancestral climate, one of which is higher rates of prostate cancer due to lack of vitamin D. If darker skin is a problem in cooler climates with fewer UV rays, then lighter skin, since it ensures better vitamin D synthesis, will be selected for. White skin ensures better and more vitamin D absorption in colder climates with fewer UV rays, therefore, the ultimate cause of the evolution of white skin is a lack of sunlight and therefore fewer UV rays. This is because white skin absorbs more UV rays which is better vitamin D synthesis.

Peter Frost believes that Europeans became white 11,000 years ago. However, as shown above, white skin evolved around 8kya. Further, contrary to popular belief, Europeans did not gain the alleles for white skin from Neanderthals (Beleza et al, 2012). European populations did not lose their dark skin immediately upon entering Europe—and Neanderthal interbreeding didn’t immediately confer the advantageous white skin alleles. There was interbreeding between AMH and Neanderthals (Sankararaman et al, 2014). So if interbreeding with Neanderthals didn’t infer white skin to proto-Europeans, then what did?

A few alleles spreading into Europe that only reached fixation a few thousand years ago. White skin is a relatively recent trait in Man (Beleza et al, 2012). People assume that white skin has been around for a long time, and that Europeans 40,000 ya are the ancestors of Europeans alive today. That, however, is not true. Modern-day European genetic history began about 6,500 ya. That is when the modern-day European phenotype arose—along with white skin.

Furthermore, Eurasians were still a single breeding population 40 kya, and only diverged recently, about 25,000 to 40,000 ya (Tateno et al, 2014). The alleles that code for light skin evolved after the Eurasian divergence. Polymorphisms in the genes ASIP and OCA2 may code for dark and light skin all throughout the world, whereas SLC24A5, MATP, and TYR have a predominant role in the evolution of light skin in Europeans but not East Asians, which suggests recent convergent evolution of a lighter pigmentation phenotype in European and East Asian populations (Norton et al, 2006). Since SLC24A5, MATP, and TYR are absent in East Asian populations, then that means that East Asians evolved light skin through completely different mechanisms than Europeans. So after the divergence of East Asians and Europeans from a single breeding population 25-40kya, there was convergent evolution for light pigmentation in both populations with the same selection pressure (low UV).

Some populations, such as Arctic peoples, don’t have the skin color one would predict they should have based on their ancestral environment. However, their diets are high in shellfish which is high in vitamin D, which means they can afford to remain darker-skinned in low UV areas. UV rays reflect off of the snow and ice in the summer and their dark skin protects them from UV light.

Black-white differences in UV absorption

If white skin evolved to better synthesize vitamin D with fewer (and less intense) UV rays, then those with blacker skin would need to spend a longer time in UV light to synthesize the same amount of vitamin D. Skin pigmentation, however, is negatively correlated with vitamin D synthesis (Libon, Cavalier, and Nikkels, 2013). Black skin is less capable of vitamin D synthesis. Furthermore, blacks’ skin color leads to an evolutionary environmental mismatch. Black skin in low UV areas is correlated with rickets (Holick, 2006), higher rates of prostate cancer due to lower levels of vitamin D (Gupta et al, 2009; vitamin D supplements may also keep low-grade prostate cancer at bay).

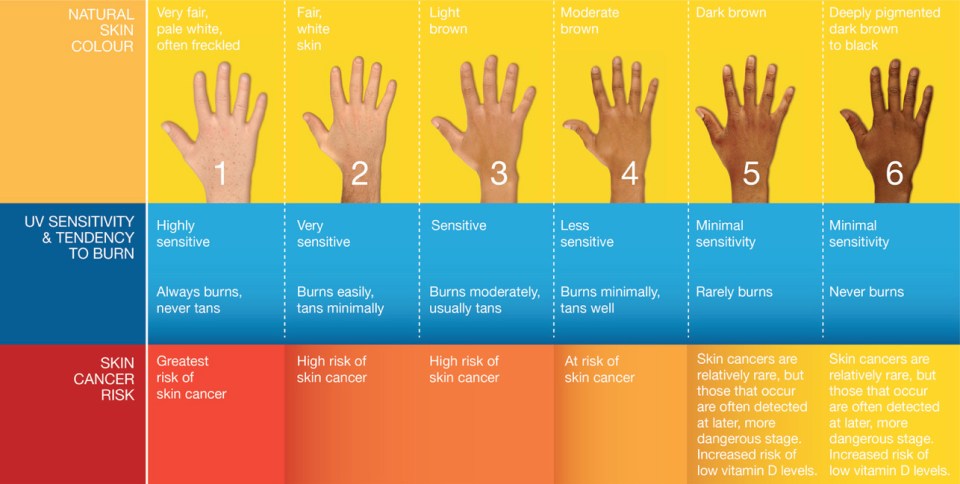

Libon, Cavalier, and Nikkels, (2013) looked at a few different phototypes (skin colors) of black and white subjects. The phototypes they looked at were II (n=19), III (n=1), and VI (n-11; whites and blacks respectively). Phototypes are shown in the image below.

To avoid the influence of solar UVB exposure, this study was conducted in February. On day 0, both the black and white subjects were vitamin D deficient. The median levels of vitamin D in the white subjects was 11.9 ng/ml whereas for the black subjects it was 8.6 ng/ml—a non-statistically significant difference. On day two, however, concentrations of vitamin D in the blood rose from 11.9 to 13.3 ng/ml—a statistically significant difference. For the black cohort, however, there was no statistically significant difference in vitamin D levels. On day 6, levels in the white subjects rose from 11.6 to 14.3 ng/ml whereas for the black subjects it was 8.6 to 9.57 ng/ml. At the end of day 6, there was a statistically significant difference in circulating vitamin D levels between the white and black subjects (14.3 ng/ml compared to 9.57 ng/ml).

Different phototypes absorb different amounts of UV rays and, therefore, peoples with different skin color absorb different levels of vitamin D. Lighter-skinned people absorb more UV rays than darker-skinned people, showing that white skin’s primary cause is to synthesize vitamin D.

UVB exposure increases vitamin D production in white skin, but not in black skin. Pigmented skin, on the other hand, hinders the transformation of 7-dehydrocholesterol to vitamin D. This is why blacks have higher rates of prostate cancer—they are outside of their ancestral environment and what comes with being outside of one’s ancestral environment are evolutionary mismatches. We have now spread throughout the world, and people with certain skin colors may not be adapted for their current environment. This is what we see with black Americans as well as white Americans who spend too much time in climes that are not ancestral to them. Nevertheless, different-colored skin does synthesize vitamin D differently, and knowledge of this will increase the quality of life for everyone.

Even the great Darwin wrote about differences in human skin color. He didn’t touch human evolution in On the Origin of Species (Darwin, 1859), but he did in his book Descent of Man (Darwin, 1871). Darwin talks about the effects of climate on skin color and hair, writing:

It was formerly thought that the colour of the skin and the character of the hair were determined by light or heat; and although it can hardly be denied that some effect is thus produced, almost all observers now agree that the effect has been very small, even after exposure during many ages. (Darwin, 1871: 115-116)

Darwin, of course, championed sexual selection as the cause for human skin variation (Darwin, 1871: 241-250). Jared Diamond has the same view, believing that natural selection couldn’t account for hair loss, black skin and white skin weren’t products of natural selection, but female mate preference and sexual selection (Greaves, 2014).

Parental selection for white skin

Judith Rich Harris, author of the book The Nurture Assumption: Why Kids Turn Out the Way They Do (Harris, 2009), posits another hypothesis for the evolution of light skin for those living in northern latitudes—parental selection. This hypothesis may be controversial to some, as it states that dark skin is not beautiful and that white skin is.

Harris posits that selection for lighter skin was driven by sexual selection, but states that parental selection for lighter skin further helped the fixation of the alleles for white skin in northern populations. Neanderthals were a furry population, as they had no clothes, so, logic dictates that if they didn’t have clothes then they must have had some sort of protection against the cold Ice Age climate, therefore they must have had fur.

Harris states that since lighter skin is seen as more beautiful than darker skin, then if a woman birthed a darker/furrier babe than the mother would have committed infanticide. Women who birth at younger ages are more likely to commit infanticide, as they still have about twenty years to birth a babe. On the other hand, infanticide rates for mothers decrease as she gets older—because it’s harder to have children the older you get.

Harris states that Erectus may have been furry up until 2 mya, however, as I’ve shown, Erectus was furless and had the ability to thermoregulate—something that a hairy hominin was not able to do (Lieberman, 2015).

There is a preference for lighter-skinned females all throughout the world, in Africa (Coetzee et al, 2012); China and India (Naidoo et al, 2016; Dixson et al, 2007); and Latin America and the Philipines (Kiang and Takeuchi, 2009). Light skin is seen as attractive all throughout the world. Thus, since light skin allows better synthesize of vitamin D in colder climes with fewer UV rays, then there would have been a myriad of selective pressures to push that along—parental selection for lighter-skinned babes being one of them. This isn’t talked about often, but infanticide and rape have both driven our evolution (more on both in the future).

Harris’ parental selection hypothesis is plausible, and she does use the right dates for fur loss which coincides with the endurance running of Erectus and how he was able to thermoregulate body heat due to lack of fur and more sweat glands. This is when black skin began to evolve. So with migration into more northerly climes, lighter-skinned people would have more of an advantage than darker-skinned people. Infanticide is practiced all over the world, and is caused—partly—by a mother’s unconscious preferences.

Skin color and attractiveness

Lighter skin is seen as attractive all throughout the world. College-aged black women find lighter skin more attractive (Stephens and Thomas, 2012). It is no surprise that due to this, a lot of black women lighten their skin with chemicals.

In a sample of black men, lighter-skinned blacks were more likely to perceive discrimination than their darker-skinned counterparts (Uzogara et al, 2014). Further, in appraising skin color’s effect on in-group discrimination, medium-skinned black men perceived less discrimination than lighter- and darker-skinned black men. Lastly—as is the case with most studies—this effect was particularly pronounced for those in lower SES brackets. Speaking of SES, lighter-skinned blacks with higher income had lower blood pressure than darker-skinned blacks with higher income (Sweet et al, 2007). The authors conclude that a variety of psychosocial stress due to discrimination must be part of the reason why darker-skinned blacks with a high SES have worse blood pressure—but I think there is something else at work here. Darker skin on its own is associated with high blood pressure (Mosley et al, 2000). I don’t deny that (perceived) discrimination can and does heighten blood pressure—but the first thing that needs to be looked at is skin color.

Lighter-skinned women are seen as more attractive (Stephen et al, 2009). This is because it signals fertility, femininity, and youth. One more important thing it signals is the ability to carry a healthy child to term since lighter skin in women is associated with better vitamin D synthesis which is important for a growing babe.

Skin color and intelligence

There is a high negative correlation between skin color and intelligence, about –.92 (Templer and Arikawa, 2006). They used the data from Lynn and Vanhanen’s 2002 book IQ and the Wealth of Nations and found that there was an extremely strong negative correlation between skin color and IQ. However, data wasn’t collected for all countries tested and for half of the countries the IQs were ‘estimated’ from other surrounding countries’ IQs.

Jensen (2006) states that the main limitation in the study design of Arikawa and Templer (2006) is that “correlations obtained from this type of analysis are completely non-informative regarding any causal or functional connection between individual differences in skin pigmentation and individual differences in IQ, nor are they informative regarding the causal basis of the correlation, e.g., simple genetic association due to cross-assortative mating for skin color and IQ versus a pleiotropic correlation in which both of the phenotypically distinct but correlated traits are manifested by one and the same gene.”

Lynn (2002) purported to find a correlation of .14 in a representative sample of American blacks (n=430), concluding that the proportion of European genes in African Americans dictates how intelligent that individual black is. However, Hill (2002) showed that when controlling for childhood environmental factors such as SES, the correlation disappears and therefore, a genetic causality cannot be inferred from the data that Lynn (2002) used.

Since Lynn found a .14 correlation between skin color and IQ in black Americans, that means that only .0196 percent of the variation in IQ within black American adults can be explained by skin color. This is hardly anything to look at and keep in mind when thinking about racial differences in IQ.

However, other people have different ideas. Others may say that since animal studies find that lighter animals are less sexually active, are less aggressive, have a larger body mass, and greater stress resistance. So since this is seen in over 40 species of vertebrate, some fish species, and over 30 bird species (Rushton and Templer, 2012) that means that it should be a good predictor for human populations. Except it isn’t.

we know the genetic architecture of pigmentation. that is, we know all the genes (~10, usually less than 6 in pairwise between population comparisons). skin color varies via a small number of large effect trait loci. in contrast, I.Q. varies by a huge number of small effect loci. so logically the correlation is obviously just a correlation. to give you an example, SLC45A2 explains 25-40% of the variance between africans and europeans.

long story short: it’s stupid to keep repeating the correlation between skin color and I.Q. as if it’s a novel genetic story. it’s not. i hope don’t have to keep repeating this for too many years.

Finally, variation in skin color between human populations are primarily due to mutations on the genes MC1R, TYR, MATP (Graf, Hodgson, and Daal, 2005), and SLC24A5 (also see Lopez and Alonso, 2014 for a review of genes that account for skin color) so human populations aren’t “expected to consistently exhibit the associations between melanin-based coloration and the physiological and behavioural traits reported in our study” (Ducrest, Keller, and Roulin, 2008). Talking about just correlations is useless until causality is established (if it ever is).

Conclusion

The evolution of human skin variation is complex and is driven by more than one variable, but some are stronger than others. The evolution of black skin evolved—in part—due to skin cancer after we lost our fur. White skin evolved due to sexual selection (proximate cause) and to better absorb UV rays for vitamin D synthesis in colder climes (the true need for light skin in cold climates). Eurasians split around 40kya, and after this split both evolved light skin pigmentation independently. As I’ve shown, the alleles that code for skin color between blacks and whites don’t account for differences in aggression, nor do they account for differences in IQ. The genes that control skin color (about a dozen) pale in comparison to the genes that control intelligence (thousands of genes with small effects). Some other hypotheses for the evolution of white skin are on par with being as controversial as the hypothesis that skin color and intelligence co-evolved—mainly that mothers would kill darker-skinned babies because they weren’t seen as beautiful as lighter-skinned babies.

The evolution of human skin variation is extremely interesting with many competing hypotheses, however, to draw wild conclusions based on just correlations in regards to human skin color and intelligence and aggression, you’re going to need more evidence than just correlations.

References

Bang KM, Halder RM, White JE, Sampson CC, Wilson J. 1987. Skin cancer in black Americans: A review of 126 cases. J Natl Med Assoc 79:51–58

Beleza, S., Santos, A. M., Mcevoy, B., Alves, I., Martinho, C., Cameron, E., . . . Rocha, J. (2012). The Timing of Pigmentation Lightening in Europeans. Molecular Biology and Evolution,30(1), 24-35. doi:10.1093/molbev/mss207

Blum, H. F. (1961). Does the Melanin Pigment of Human Skin Have Adaptive Value?: An Essay in Human Ecology and the Evolution of Race. The Quarterly Review of Biology,36(1), 50-63. doi:10.1086/403275

Coetzee V, Faerber SJ, Greeff JM, Lefevre CE, Re DE, et al. (2012) African perceptions of female attractiveness. PLOS ONE 7: e48116.

Darwin, C. (1859). On the origin of species by means of natural selection, or, the preservation of favoured races in the struggle for life. London: J. Murray.

Darwin, C. (1871). The descent of man, and selection in relation to sex. London: John Murray, Albemarle Street.

Dixson, B. J., Dixson, A. F., Li, B., & Anderson, M. (2006). Studies of human physique and sexual attractiveness: Sexual preferences of men and women in China. American Journal of Human Biology,19(1), 88-95. doi:10.1002/ajhb.20584

Ducrest, A., Keller, L., & Roulin, A. (2008). Pleiotropy in the melanocortin system, coloration and behavioural syndromes. Trends in Ecology & Evolution,23(9), 502-510. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2008.06.001

Frost, P. (2007). Human skin-color sexual dimorphism: A test of the sexual selection hypothesis. American Journal of Physical Anthropology,133(1), 779-780. doi:10.1002/ajpa.20555

Graf, J., Hodgson, R., & Daal, A. V. (2005). Single nucleotide polymorphisms in theMATP gene are associated with normal human pigmentation variation. Human Mutation,25(3), 278-284. doi:10.1002/humu.20143

Greaves, M. (2014). Was skin cancer a selective force for black pigmentation in early hominin evolution? Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences,281(1781), 20132955-20132955. doi:10.1098/rspb.2013.2955

Gupta, D., Lammersfeld, C. A., Trukova, K., & Lis, C. G. (2009). Vitamin D and prostate cancer risk: a review of the epidemiological literature. Prostate Cancer and Prostatic Diseases,12(3), 215-226. doi:10.1038/pcan.2009.7

Guthrie RD. 1970. Evolution of human threat display organs. Evol Biol 4:257–302.

Harris, J. R. (2006). Parental selection: A third selection process in the evolution of human hairlessness and skin color. Medical Hypotheses,66(6), 1053-1059. doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2006.01.027

Harris, J. R. (2009). The nurture assumption: why children turn out the way they do. New York: Free Press.

Hill, Mark E. 2002. Skin color and intelligence in African Americans: A reanalysis of Lynn’s data. Population and Environment 24, no. 2:209–14

Holick, M. F. (2006). Resurrection of vitamin D deficiency and rickets. Journal of Clinical Investigation,116(8), 2062-2072. doi:10.1172/jci29449

Jablonski, N. G., & Chaplin, G. (2000). The evolution of human skin coloration. Journal of Human Evolution,39(1), 57-106. doi:10.1006/jhev.2000.0403

Jablonski, N. G., & Chaplin, G. (2014). Skin cancer was not a potent selective force in the evolution of protective pigmentation in early hominins. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences,281(1789), 20140517-20140517. doi:10.1098/rspb.2014.0517

Jensen, A. R. (2006). Comments on correlations of IQ with skin color and geographic–demographic variables. Intelligence,34(2), 128-131. doi:10.1016/j.intell.2005.04.003

Kiang, L., & Takeuchi, D. T. (2009). Phenotypic Bias and Ethnic Identity in Filipino Americans. Social Science Quarterly,90(2), 428-445. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6237.2009.00625.x

Libon, F., Cavalier, E., & Nikkels, A. (2013). Skin Color Is Relevant to Vitamin D Synthesis. Dermatology,227(3), 250-254. doi:10.1159/000354750

Lieberman, D. E. (2015). Human Locomotion and Heat Loss: An Evolutionary Perspective. Comprehensive Physiology, 99-117. doi:10.1002/cphy.c140011

Lieberman, D. E., Raichlen, D. A., Pontzer, H., Bramble, D. M., & Cutright-Smith, E. (2006). The human gluteus maximus and its role in running. Journal of Experimental Biology,209(11), 2143-2155. doi:10.1242/jeb.02255

López, S., & Alonso, S. (2014). Evolution of Skin Pigmentation Differences in Humans. ELS. doi:10.1002/9780470015902.a0021001.pub2

Lynn, R. (2002). Skin color and intelligence in African Americans. Population and Environment, 23, 365–375.

Mosley, J. D., Appel, L. J., Ashour, Z., Coresh, J., Whelton, P. K., & Ibrahim, M. M. (2000). Relationship Between Skin Color and Blood Pressure in Egyptian Adults : Results From the National Hypertension Project. Hypertension,36(2), 296-302. doi:10.1161/01.hyp.36.2.296

Naidoo, L.; Khoza, N.; Dlova, N.C. A fairer face, a fairer tomorrow? A review of skin lighteners. Cosmetics 2016, 3, 33.

Norton, H. L., Kittles, R. A., Parra, E., Mckeigue, P., Mao, X., Cheng, K., . . . Shriver, M. D. (2006). Genetic Evidence for the Convergent Evolution of Light Skin in Europeans and East Asians. Molecular Biology and Evolution,24(3), 710-722. doi:10.1093/molbev/msl203

Rushton, J. P., & Templer, D. I. (2012). Do pigmentation and the melanocortin system modulate aggression and sexuality in humans as they do in other animals? Personality and Individual Differences,53(1), 4-8. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2012.02.015

Sankararaman, S., Mallick, S., Dannemann, M., Prüfer, K., Kelso, J., Pääbo, S., . . . Reich, D. (2014). The genomic landscape of Neanderthal ancestry in present-day humans. Nature,507(7492), 354-357. doi:10.1038/nature12961

Stephen, I. D., Smith, M. J., Stirrat, M. R., & Perrett, D. I. (2009). Facial Skin Coloration Affects Perceived Health of Human Faces. International Journal of Primatology,30(6), 845-857. doi:10.1007/s10764-009-9380-z

Stephens, D., & Thomas, T. L. (2012). The Influence of Skin Color on Heterosexual Black College Women’s Dating Beliefs. Journal of Feminist Family Therapy,24(4), 291-315. doi:10.1080/08952833.2012.710815

Sweet, E., Mcdade, T. W., Kiefe, C. I., & Liu, K. (2007). Relationships Between Skin Color, Income, and Blood Pressure Among African Americans in the CARDIA Study. American Journal of Public Health,97(12), 2253-2259. doi:10.2105/ajph.2006.088799

Tateno, Y., Komiyama, T., Katoh, T., Munkhbat, B., Oka, A., Haida, Y., . . . Inoko, H. (2014). Divergence of East Asians and Europeans Estimated Using Male- and Female-Specific Genetic Markers. Genome Biology and Evolution,6(3), 466-473. doi:10.1093/gbe/evu027

Templer, D. I., & Arikawa, H. (2006). Temperature, skin color, per capita income, and IQ: An international perspective. Intelligence,34(2), 121-139. doi:10.1016/j.intell.2005.04.002

Uzogara, E. E., Lee, H., Abdou, C. M., & Jackson, J. S. (2014). A comparison of skin tone discrimination among African American men: 1995 and 2003. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 15(2), 201–212. http://doi.org/10.1037/a0033479

van den Berghe PL, Frost P. 1986. Skin color preference, sexual dimorphism and sexual selection: a case of gene-culture coevolution? Ethn Racial Stud 9:87–113.

Racial Differences in Somatype

1750 words

One’s somatype is, really, the first thing they notice. Somatypes are broken down into three categories: ectomorph (skinny build), endomorph (rounder, fatter build) and mesomorph (taller, more muscular build). Like numerous other traits, different races and ethnies fall somewhere in between these three soma categories. Africans are meso, while Europeans are endo, while East Asians are more endo than Europeans. Differences in somatype, too, lead to the expected racial differences in sports due to differing anatomy and fat mass.

History of somatyping

The somatype classification was developed by psychiatrist William Sheldon in the 1940s, while releasing a book in 1954 titled Atlas of Men: Somatotyping the Adult Male At All Ages. He theorized that one’s somatype could predict their behavior, intelligence, and where they place socially. Using nude posture photos from his Ivy League students, he grouped people into three categories based on body measurements and ratios—mesomorph, endomorph, and ectomorph. Clearly, his theory is not backed by modern psychology, but I’m not really interested in that. I’m interested in the somatyping.

Somatypes

The three somatypes are endomorph, mesomorph, and ectomorph. Each type has different leverages and body fat distribution. Endomorphs are rounder, with short limbs, a large trunk, carry more fat in the abdomen and lower body, large chest, wide hips, and has hardly any muscular definition, yet gain strength easily. Ectomorphs, on the other hand, are taller, lankier with longer limbs, a narrow chest, thin body, short trunk and has little muscle.

There are further subdivisions within the three main types, mesomorphic-endomorph (meso-dominant), mesomorph-endomorph (both types are equal with less ectomorphy), ectomorphic-mesomorph, endomorphic-mesomorph, endomorph-ectomorph, and ectomorphic-endomorph. This can be denoted as “7-1-1”, which would indicate pure endomorph, “1-7-1” would indicate pure mesomorph and “1-1-7” would be a pure ectomorph. Further breakdowns can be made such as “1.6-2.7-6.4”, indicating the somatype is ecto-dominant. On the scale, 1 is extremely low while 7 is extremely high. The races, however, fall along racial lines as well.

Racial differences in somatype

West Africans and their descendants are the most mesomorphic. They also have the highest amount of type II muscle fibers which is a leading cause of their success in sporting events which call for short bursts of speed. Due to having longer limbs, they have a longer stride and can generate more speed. West Africans also have the narrowest hips out of all of the races (Rushton, 1997: 163) which further leads to their domination in sprinting competitions and events that take quick bursts of speed and power. However much success their morphology lends them in these types of competitions, their somatype hampers them when it comes to swimming. The first black American qualified for the Olympic swimming team in the year 2000. This is due to a narrower chest cavity and denser, heavier bones.

East Africans are most ectomorphic which you can see by their longer limbs and skinnier body. They have an average BMI of 21.6, one of the lowest in the world. Their low BMI, ectomorphic somatype and abundance of slow twitch muscle fibers are why they dominate in distance running events. Many explanations have been proposed to explain why East Africans (specifically Kenyans and Ethiopians) dominate distance running. The main factor is their somatype (ectomorphic) (Wilbur and Pitsiladis, 2012). The authors, however, downplay other, in my opinion, more important physiologic characteristics such as muscle fiber typing, and differences in physiology. Of course their somatype matters for why they dominate, but other important physiologic characteristics do matter. They clearly evolved together so you cannot separate them.

Europeans are more endo than East Africans and West Africans but less so than East Asians. Europeans have a strong upper body, broad shoulders, longer and thicker trunk and shorter extremities along with 41 percent slow twitch fibers compared to blacks’ 33 percent slow twitch fibers. This is why Europeans dominate power sports such as powerlifting and the World’s Strongest Man. Eighty to 100 percent of the differences in total variation in height, weight, and BMI between East Asians and Europeans are associated with genetic differences (Hur et al, 2008). If the variation between East Asians and Europeans on height, weight and BMI are largely attributed to genetic factors, then the same, I assume, should be true for Africans and Europeans/East Asians.

East Asians are the most endomorphic race and have lighter skeletons and more body fat. They have short arms and legs with a large trunk, which is a benefit when it comes to certain types of lifting movements (such as Olympic lifting, where East Asians shine) but hampers them when it comes to sprinting and distance running (although they have higher rates of type I fibers). East Asians also have more body fat at a lower BMI which is further evidence for the endomorphic somatype. This is also known as ‘TOFI’, ‘Thin on the Outside, Fat on the Inside’. Chinese and Thai children had a higher waist circumference and higher trunk fat deposits than Malay and Lebanese children (Liu et al, 2011). This is a classic description of the endomorphic individual.

Human hands and feet are also affected by climate. Climatic variation played a role in shaping the racial somatic differences we see today. The differences seen in hands and feet “might be due to the presence of evolutionary constraints on the foot to maintain efficient bipedal locomotion” (Betti et al, 2015).

Black-white differences in somatype

Fifty percent of the variability in lean mass is due to genetic factors (Arden and Specter, 1997) with the heritability of stature 85 percent in a meta-analysis (Peeters et al, 2009). Racial differences in somatype are also seen at a young age (Malina, 1969). Blacks had better muscular development and less fat-free mass at an early age. Vickery et al (1988) argued that since blacks have thinner skin folds that caliper measurements testing differences in body fat would be skewed. Malina (1969) also reports the same. Note that Malina’s paper was written in 1969, literally right before it got pushed on the American populace that fat was bad and carbohydrates were good.

Looking at the two tables cited by Malina (1969) on somatype we can see the difference between blacks and whites.

| Data from Malina, (1969: 438) | n | Mesomorph | Ectomorph | Endomorph |

| Blacks | 65 | 5.14 | 2.99 | 2.92 |

| Whites | 199 | 4.29 | 2.89 | 3.86 |

| Data from Malina (1969: 438) | Blacks | Whites |

| Thin-build body type | 8.93 | 5.90 |

| Submedium fatty development | 48.31 | 29.39 |

| Medium fleshiness | 33.69 | 43.63 |

| Fat and very fat categories | 9.09 | 21.06 |

Since this data was collected literally before we went down the wrong path and wrongly demonized fat and (wrongly) championed carbohydrates, this is an outstanding look at somatype/fat mass before the obesity epidemic. There is a clear trend, with blacks being more likely to have lower levels of fat-free body mass while also more likely to be mesomorphic. This has a ton of implications for racial differences in sports.

Somatype is predicated on lean mass, stature, bone density and fat-free body mass. Since racial differences appear in somatype at an early age, there is a great chance that the differences in somatype are genetic in nature.

College (American) football players are more likely to be endo-mesomorphs while high-school football players were more likely to be mesomorphs (Bale et al, 1994). This partly explains black over representation in football. Further, basketball, handball, and soccer players in Nigeria were taller, heavier, and had lower percent body fat than other athletic groups (Mazur, Toriola, and Igobokwe, 1985). Somatic differences have a lot to do with domination in sports competition.

Somatic differences are also seen in boxing. Elite boxers are more likely to have a mesomorphic somatype compared to non-athletes. Higher weight divisions were also more likely to be mesomorphic and endomorphic than the lower weight divisions which skewed ectomorphic (Noh et al, 2014). Blacks do well in boxing since they have a more mesomorphic somatype. Due to their higher levels of type II fibers, they can be quicker and throw more forceful punches which translates to boxing success.

Conclusion

Racial differences in somatype are another key to the puzzle to figure out why the races differ in elite sporting competition. The races evolved in different geographic locations which then led to differences in somatype. West African sports dominance is explained by their somatype, muscle fiber type, and physiology. The same can be said for Europeans in strength sports/powerlifting sports, and East Asians with ping-pong and some strength sports (though, due to lower muscle mass they are the least athletic of the races). I am not, of course, denying the impact of determination to succeed or training of any kind. What one must realize, however, is that one with the right genetic makeup/somatype and elite training will, way more often than not, outperform an individual with the wrong genetic makeup/somatype and elite training. These inherent differences between races explain the disparities in elite sporting competitions.

References

Arden, N. K., & Spector, T. D. (1997). Genetic Influences on Muscle Strength, Lean Body Mass, and Bone Mineral Density: A Twin Study. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research,12(12), 2076-2081. doi:10.1359/jbmr.1997.12.12.2076

Bale P, Colley E, Mayhew JL, et al. Anthropometric and somatotype variables related to strength in American football players. J Sports Med Phys Fitness 1994;34:383–9

Betti, L., Lycett, S. J., Cramon-Taubadel, N. V., & Pearson, O. M. (2015). Are human hands and feet affected by climate? A test of Allen’s rule. American Journal of Physical Anthropology,158(1), 132-140. doi:10.1002/ajpa.22774

Hur, Y., Kaprio, J., Iacono, W. G., Boomsma, D. I., Mcgue, M., Silventoinen, K., . . . Mitchell, K. (2008). Genetic influences on the difference in variability of height, weight and body mass index between Caucasian and East Asian adolescent twins. International Journal of Obesity,32(10), 1455-1467. doi:10.1038/ijo.2008.144

Liu, A., Byrne, N. M., Kagawa, M., Ma, G., Kijboonchoo, K., Nasreddine, L., . . . Hills, A. P. (2011). Ethnic differences in body fat distribution among Asian pre-pubertal children: A cross-sectional multicenter study. BMC Public Health,11(1). doi:10.1186/1471-2458-11-500

Malina, R. M. (1969). Growth and Physical Performance of American Negro and White Children: A Comparative Survey of Differences in Body Size, Proportions and Composition, Skeletal Maturation, and Various Motor Performances. Clinical Pediatrics,8(8), 476-483. doi:10.1177/000992286900800812

Mathur, D. N., Toriola, A. L., & Igbokwe, N. U. (1985). Somatotypes of Nigerian athletes of several sports. British Journal of Sports Medicine,19(4), 219-220. doi:10.1136/bjsm.19.4.219

Noh, J., Kim, J., Kim, M., Lee, J., Lee, L., Park, B., . . . Kim, J. (2014). Somatotype Analysis of Elite Boxing Athletes Compared with Nonathletes for Sports Physiotherapy. Journal of Physical Therapy Science,26(8), 1231-1235. doi:10.1589/jpts.26.1231

Peeters, M., Thomis, M., Beunen, G., & Malina, R. (2009). Genetics and Sports: An Overview of the Pre-Molecular Biology Era. Genetics and Sports Medicine and Sport Science, 28-42. doi:10.1159/000235695

Rushton J P (1997). Race, Evolution, and Behavior. A Life History Perspective (Transaction, New Brunswick, London).

Vickery SR, Cureton KJ, Collins MA. Prediction of body density from skinfolds in black and white young men. Hum Biol 1988;60:135–49.

Wilber, R. L., & Pitsiladis, Y. P. (2012). Kenyan and Ethiopian Distance Runners: What Makes Them so Good? International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance,7(2), 92-102. doi:10.1123/ijspp.7.2.92

Possibly Retracting My Article on HBD and Baseball

700 words

I am currently reading Taboo: Why Black Athletes Dominate Sports and Why We’re Afraid To Talk About It and came across a small section in the beginning of the book talking about black-white differences in baseball. It appears I am horribly, horribly wrong and it looks like I may need to retract my article HBD and Sports: Baseball. However, I don’t take second-hand accounts as gospel, so I will be purchasing the book that Entine cites, The Bill James Baseball Abstract 1987 to look into it myself and I may even do my own analysis on modern-day players to see if this still holds. Nevertheless, at the moment disregard the article I wrote last year until I look into this myself.

Excerpt from Taboo: Why Black Athletes Dominate Sports and Why We’re Afraid To Talk About It:

Baseball historian Bill James, author of dozens of books on the statistical twists of his favorite sport believes this trend [black domination in baseball] is not a fluke. In an intriguing study conducted in 1987, he compared the careers of hundreds of rookies to figure out what qualities best predict who would develop into stars. He noted many intangible factors, such as whether a player stays fit or is just plain lucky. The best predictors of long-term career success included the age of the rookie, his defensive position as a determinant in future hitting success (e.g., catchers fare worse than outfielders), speed, and the quality of the player’s team. But all of these factors paled when compared to the color of the player’s skin.

“Nobody likes to write about race,” James noted apologetically. “I thought I would do a [statistical] run of black players against white players, fully expecting that it would show nothing in particular or nothing beyond the outside range of chance, and I would file it away and never mention that I had looked at the issue at all.

James first compared fifty-four white rookies against the same number of black first-year players who had comparable statistics. “The results were astonishing,” James wrote. The black players:

* went on to have better major-league careers in 44 out of 54 cases

* played 48 percent more games

* had 66 percent more major league hits

* hit 93 percent more triples

* hit 66 percent more home runs

* scored 69 percent more runs

* stole 400 more bases (Entine, 2000: 22-23)

…

Flabbergasted at what he found, James ran a second study using forty-nine black/white comparisons. Again, blacks proved more durable, retained their speed longer, and were consistently better hitters. For example, he compared Ernie Banks, a power hitting shortstop for the Chicago Cubs, and Bernie Allen who broke in with Minnesota. They both reached the majors when they were twenty-three years old, were the same height and weight, and were considered equally fast. Over time, Allen bombed and Banks landed in the Hall of Fame. (Entine, 2000: 24)

…

In an attempt to correct for possible bias, James compared players with comparable speed statistics such as the number of doubles, triples, and stolen bases. He ran a study focused on players who had little speed. He analyzed for “position bias” and made sure that players in the same eras were being compared. Yet every time he crunched the numbers, the results broke down across racial lines. When comparing home runs, runs scored, RBIs or stolen bases, black players held an advantage a startling 80 percent of the time. “And I could identify absolutely no bias to help explain why this should happen,” James said in disbelief.

James also compared white Hispanic rookies whom he assumed faced an uphill battle similar to that for blacks, with comparable groups of white and black players. The blacks dominated the white Latinos by even more than they did white North Americans, besting them in 19 of the 26 comparisons. Blacks played 62 percent more games, hit 192 more home runs, drove in 125 percent more runs, and stole 30 percent more bases.

So why have blacks become the stars of baseball far out of proportion to their relative numbers? James eventually concluded that there were two possible explanations: “Blacks are better athletes because they are born better athletes, which is to say that it is genetic, or that they are born equal and become better athletes. (Entine, 2000: 24-25)

Black-White Differences in Muscle Fiber and Its Role In Disease and Obesity

1700 words

How do whites and blacks differ by muscle fiber and what does it mean for certain health outcomes? This is something I’ve touched on in the past, albeit briefly, and decided to go in depth on it today. The characteristics of skeletal muscle fibers dictate whether one has a higher or lower chance of being affected by cardiometabolic disease/cancer. Those with more type I fibers have less of a chance of acquiring diabetes while those with type II fibers have a higher chance of acquiring debilitating diseases. This has direct implications for health disparities between the two races.

Muscle fiber typing by race

Racial differences in muscle fiber typing explain differences in strength and mortality. I have, without a shadow of a doubt, proven this. So since blacks have higher rates of type II fibers while whites have higher rates of type I fibers (41 percent type I for white Americans, 33 percent type I for black Americans, Ama et al, 1985) while West Africans have 75 percent fast twitch and East Africans have 25 percent fast twitch (Hobchachka, 1988). Further, East and West Africans differ in typing composition, 75 percent fast for WAs and 25 percent fast for EAs, which has to do with what type of environment they evolved in (Hochhachka, 1998). What Hochhachka (1998) also shows is that high latitude populations (Quechua, Aymara, Sherpa, Tibetan and Kenyan) “show numerous similarities in physiological hypoxia defence mechanisms.” Clearly, slow-twitch fibers co-evolved here.

Clearly, slow-twitch fibers co-evolved with hypoxia. Since hypoxia is the deficiency in the amount of oxygen that reaches the tissues, populations in higher elevations will evolve hypoxia defense mechanisms, and with it, the ability to use the oxygen they do get more efficiently. This plays a critical role in the fiber typing of these populations. Since they can use oxygen more efficiently, they then can become more efficient runners. Of course, these populations have evolved to be great distance runners and their morphology followed suit.

Caesar and Henry (2015) also show that whites have more type I fibers than blacks who have more type II fibers. When coupled with physical inactivity, this causes higher rates of cancer and cardiometabolic disease. Indeed, blacks have higher rates of cancer and mortality than whites (American Cancer Society, 2016), both of which are due, in part, to muscle fiber typing. This could explain a lot of the variation in disease acquisition in America between blacks and whites. Physiologic differences between the races clearly need to be better studied. But we first must acknowledge physical differences between the races.

Disease and muscle fiber typing

Now that we know the distribution of fiber types by race, we need to see what type of evidence there is that differing muscle fiber typing causes differences in disease acquisition.

Those with fast twitch fibers are more likely to acquire type II diabetes and COPD (Hagiwara, 2013); cardiometabolic disease and cancer (Caesar and Henry, 2015); a higher risk of cardiovascular events (Andersen et al, 2015, Hernelahti et al, 2006); high blood pressure, high heart rate, and unfavorable left ventricle geometry leading to higher heart disease rates and obesity (Karjalainen et al, 2006) etc. Knowing what we know about muscle fiber typing and its role in disease, it makes sense that we should take this knowledge and acknowledge physical racial differences. However, once that is done then we would need to acknowledge more uncomfortable truths, such as the black-white IQ gap.

One hypothesis for why fast twitch fibers are correlated with higher disease acquisition is as follows: fast twitch fibers fire faster, so due to mechanical stress from rapid and forceful contraction, this leads the fibers to be more susceptible to damage and thus the individual will have higher rates of disease. Once this simple physiologic fact is acknowledged by the general public, better measures can be taken for disease prevention.

Due to differences in fiber typing, both whites and blacks must do differing types of cardio to stay healthy. Due to whites’ abundance of slow twitch fibers, aerobic training is best (not too intense). However, on the other hand, due to blacks’ abundance of fast twitch fibers, they should do more anaerobic type exercises to attempt to mitigate the diseases that they are more susceptible due to their fiber typing.

Black men with more type II fibers and less type I fibers are more likely to be obese than ‘Caucasian‘ men are to be obese (Tanner et al, 2001). More amazingly, Tanner et al showed that there was a positive correlation (.72) between weight loss and percentage of type I fibers in obese patients. This has important implications for African-American obesity rates, as they are the most obese ethny in America (Ogden et al, 2016) and have higher rates of metabolic syndrome (a lot of the variation in obesity does come down food insecurity, however). Leaner subjects had higher proportions of type I fibers compared to type II. Blacks have a lower amount of type I fibers compared to whites without adiposity even being taken into account. Not surprisingly, when the amount of type I fibers was compared by ethnicity, there was a “significant interaction” with ethnicity and obesity status when type I fibers were compared (Tanner et al, 2001). Since we know that blacks have a lower amount of type I fibers, they are more likely to be obese.

In Tanner et al’s sample, both lean blacks and whites had a similar amount of type I fibers, whereas the lean blacks possessed more type I fibers than the obese black sample. Just like there was a “significant interaction” between ethnicity, obesity, and type I fibers, the same was found for type IIb fibers (which, as I’ve covered, black Americans have more of these fibers). There was, again, no difference between lean black and whites in terms of type I fibers. However, there was a difference in type IIb fibers when obese blacks and lean blacks were compared, with obese blacks having more IIb fibers. Obese whites also had more type IIb fibers than lean whites. Put simply (and I know people here don’t want to hear this), it is easier for people with type I fibers to lose weight than those with type II fibers. This data is some of the best out there showing the relationship between muscle fiber typing and obesity—and it also has great explanatory power for black American obesity rates.

Conclusion

Muscle fiber differences between blacks and whites explain disease acquisition rates, mortality rates (Araujo et al, 2010), and differences in elite sporting competition between the races. I’ve proven that whites are stronger than blacks based on the available scientific data/strength competitions (click here for an in-depth discussion). One of the most surprising things that muscle fibers dictate is weight loss/obesity acquisition. Clearly, we need to acknowledge these differences and have differing physical activity protocols for each racial group based on their muscle fiber typing. However, I can’t help but think about the correlation between strength and mortality now. This obesity/fiber type study puts it into a whole new perspective. Those with type I fibers are more likely to be physically stronger, which is a cardioprotectant, which then protects against all-cause mortality in men (Ruiz et al, 2008; Volaklis, Halle, and Meisenger, 2015). So the fact that black Americans have a lower life expectancy as well as lower physical strength and more tpe II fibers than type I fibers shows why blacks are more obese, why blacks are not represented in strength competitions, and why blacks have higher rates of disease than other populations.The study by Tanner et al (2001) shows that there obese people are more likely to have type II fibers, no matter the race. Since we know that blacks have more type II fibers on average, this explains a part of the variance in the black American obesity rates and further disease acquisition/mortality.

The study by Tanner et al (2001) shows that there obese people are more likely to have type II fibers, no matter the race. Since we know that blacks have more type II fibers on average, this explains a part of the variance in the black American obesity rates and further disease acquisition/mortality.

Differences in muscle fiber typing do not explain all of the variance in disease acquisition/strength differences, however, understanding what the differing fiber typings do, metabolically speaking, along with how they affect disease acquisition will only lead to higher qualities of life for everyone involved.

References

Araujo, A. B., Chiu, G. R., Kupelian, V., Hall, S. A., Williams, R. E., Clark, R. V., & Mckinlay, J. B. (2010). Lean mass, muscle strength, and physical function in a diverse population of men: a population-based cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health,10(1). doi:10.1186/1471-2458-10-508

Andersen K, Lind L, Ingelsson E, Amlov J, Byberg L, Miachelsson K, Sundstrom J. Skeletal muscle morphology and risk of cardiovascular disease in elderly men. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2013.

Ama PFM, Simoneau JA, Boulay MR, Serresse Q Thériault G, Bouchard C. Skeletal muscle characteristics in sedentary Black and Caucasian males. J Appl Physiol 1986: 6l:1758-1761.

American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures for African Americans 2016-2018. Atlanta: American Cancer Society, 2016.

Ceaser, T., & Hunter, G. (2015). Black and White Race Differences in Aerobic Capacity, Muscle Fiber Type, and Their Influence on Metabolic Processes. Sports Medicine,45(5), 615-623. doi:10.1007/s40279-015-0318-7

Hagiwara N. Muscle fibre types: their role in health, disease and as therapeutic targets. OA Biology 2013 Nov 01;1(1):2.

Hernelahti, M., Tikkanen, H. O., Karjalainen, J., & Kujala, U. M. (2005). Muscle Fiber-Type Distribution as a Predictor of Blood Pressure: A 19-Year Follow-Up Study. Hypertension,45(5), 1019-1023. doi:10.1161/01.hyp.0000165023.09921.34

Hochachka, P.W. (1998) Mechanism and evolution of hypoxia-tolerance in humans. J. Exp. Biol. 201, 1243–1254

Karjalainen, J., Tikkanen, H., Hernelahti, M., & Kujala, U. M. (2006). Muscle fiber-type distribution predicts weight gain and unfavorable left ventricular geometry: a 19 year follow-up study. BMC Cardiovascular Disorders,6(1). doi:10.1186/1471-2261-6-2

Ogden C. L., Carroll, M. D., Lawman, H. G., Fryar, C. D., Kruszon-Moran, D., Kit, B.K., & Flegal K. M. (2016). Trends in obesity prevalence among children and adolescents in the United States, 1988-1994 through 2013-2014. JAMA, 315(21), 2292-2299.

Ruiz, J. R., Sui, X., Lobelo, F., Morrow, J. R., Jackson, A. W., Sjostrom, M., & Blair, S. N. (2008). Association between muscular strength and mortality in men: prospective cohort study. Bmj,337(Jul01 2). doi:10.1136/bmj.a439

Tanner, C. J., Barakat, H. A., Dohm, G. L., Pories, W. J., Macdonald, K. G., Cunningham, P. R., . . . Houmard, J. A. (2001). Muscle fiber type is associated with obesity and weight loss. American Journal of Physiology – Endocrinology And Metabolism,282(6). doi:10.1152/ajpendo.00416.2001