Home » Posts tagged 'racism'

Tag Archives: racism

Racial Differences in Amputation

1850 words

Overview

An amputation is a preventative measure. It is done for a few reasons: To stop the spread of a gangrenous infection and to save more of a limb after there is no blood flow to the limb after a period of time. Other reasons are due to trauma and diabetes. Trauma, infection, and diabetes are leading causes of amputation in developing countries whereas in developed countries it is peripheral vascular disease (Sarvestani and Azam, 2013). Poor circulation to an affected limb leads to tissue death—when the tissue begins turning black, it means that there is no or low blood flow to the tissue, and to save more of the limb, the limb is amputated just above where the infection is. About 1.8 million Americans are living as amputees. After amputation, there is a phenomenon called “phantom limb” where amputees can “feel” their limb they previously had, and even feel pain to it, and it is very common in amputees; about 60-80 percent of amputees report “feeling” a phantom limb (see Collins et al, 2018; Kaur and Guan, 2018). The sensation can occur either immediately after amputation or years after. Phantom limb pain is neuropathic pain—a pain that is caused by damage to the somatosensory system (Subedi and Grossberg, 2011). Amputees even have shorter lifespans. When foot-amputation is performed due to uncontrolled diabetes, mortality ranges between 13-40 percent for year one, 35-65 percent for year 3, and 39-85 percent in year 5 (Beyaz, Guller, and Bagir, 2017).

Race and amputation

Amputation of the lower extremities are the most common amputations (Molina and Faulk, 2020). Minority populations are less likely to receive preventative care, such as preventative vascular screenings and care, which leads to them being more likely to undergo amputations. Such populations are more likely to suffer from disease of the lower extremities, and it is due to this that minorities undergo amputations more often than whites in America. Minorities in America—i.e., blacks and “Hispanics”—are about twice as likely as whites to undergo lower-extremity amputation (Rucker-Whitaker, Feinglass, and Pearce, 2003; Lowe and Tariman, 2008; Lefebvre and Lavery, 2011; Mustapha et al, 2017; Arya et al, 2018)—so it is an epidemic for black America. Blacks are even more likely to undergo repeat amputation (Rucker-Whitaker, Feinglass, and Pearce, 2003). In fact, here is a great essay chronicling the stories of some double-amputee black patients.

Why do blacks undergo amputations more often than whites? One answer is, of course: Physician bias. For example, after controlling for demographic, clinical, and chronic disease status, blacks were 1.7 times more likely than whites to undergo lower-leg amputations (Feinglass et al, 2005; Regenbogen et al, 2007; Lefebvre and Lavery, 2011). What is a cause of this is inequity in healthcare—note that “inequity” here means differences in care that are avoidable and unjust (Sudana and Blas, 2013).

Another reason is due to complications from diabetes. Blacks have higher rates of diabetes than whites (Rodriguez and Campbell, 2007) but see Signorello et al (2007). Muscle fiber differences between races (see also here). Differences in hours-slept between blacks and whites, too, could also explain the severity of the disease. But what could also be driving differences in diabetes between races is the fact that blacks are more likely than whites to live in “food swamps.” Food swamps are where it is hard to find nutritionally-dense food, whereas food deserts are areas where there is little access to healthy, nutritious food. In fact, a neighborhood being a food swamp is more predictive of obesity status of the population in the area than is its being a food desert (Cooksey-Stowers, Schwartz, and Brownell, 2017). Along with the slew of advertisements in that are directed to low-income neighborhoods (see Cassady, Liaw, and Miller, 2015), we can now see how such things like food swamps contribute to high hospitalization rates in low-income neighborhoods (Phillips and Rogriguez, 2019). These amputations are preventable—and so, we can say that there is a lack of equity in healthcare between races which leads to these different rates in amputation—before even thinking about physician bias. Amputation rates for blacks in the southeast can be almost seven times higher than other regions (Goodney et al, 2014).

Stapleton et al (2018: 644) conclude in their study on physician bias and amputation:

Our study demonstrates that such justifications may be unevenly applied across race, suggesting an underlying bias. This may reflect a form of racial paternalism, the general societal perception that minorities are less capable of “taking care of themselves,” even including issues related to health and disease management.23 Underlying bias may prompt more providers to consider amputation for minority patients. Furthermore, unlike in transplant surgery, there is currently no formal process for assessing patient compliance with treatment protocols or self-care in vascular surgery.24 Asking providers to make snap judgments about patient compliance, without a protocol for objective assessment, allows subconscious bias to influence patient care.

Physician bias is pervasive (Hoberman, 2012)—whether it is conscious or unconscious racial bias. Such biases can and do lead to outcomes that should not occur. By attempting to reduce disparities in healthcare that then lead to negative outcomes, we can then attempt to improve the quality of healthcare given to lower-income groups, like blacks. Such biases lead to negative health outcomes for blacks (such as the claim that blacks feel less pain than whites), and if they were addressed and conquered, then we could increase equity between groups until access to healthcare is equal—and physician bias is an impediment to access to equal healthcare due to the a priori biases that physicians may hold about certain racial/ethnic groups. Medical racism, therefore, drives a lot of the amputation differences between blacks and whites. Hospitals that are better equipped to offer revascularization services (attempting to save the limb by increasing blood flow to the affected limb) even had a higher rate of amputations in blacks when compared to whites (Durazzo, Frencher, and Gusberg, 2013).

For example. Mustapha et al (2017) write:

Compared to Caucasian patients, several studies have found that African-Americans with PAD are more likely to be amputated and less likely to have their lower limb revascularized either surgically or via an endovascular approach [3–9]. In an early analysis of data from acute-care hospitals in Florida, Huber et al. reported that the incidence of amputation (5.0 vs. 2.5 per 10,000) was higher and revascularization lower (4.0 vs. 7.1 per 10,000) among African-Americans compared to Caucasians, even though the incidence of any procedure for PAD was comparable (9.0 vs. 9.6 per 10,000) [4]. Other studies have reported that the probability of undergoing a revascularization or angioplasty was reduced by 28–49 % among African-Americans relative to Caucasians [3 6]

Pro-white unconscious biases were also found among physicians, as Kandi and Tan (2020) note:

There is evidence of both healthcare provider racism and unconscious racial biases. Green et al. found significant pro-White bias among internal medicine and emergency medicine residents, while James SA supported this finding, indicating a “pro-white” unconscious bias in physician’s attitudes towards, and interactions with, patients [43,44]. In a survey assessing implicit and explicit racial bias by Emergency Department (ED) providers in care of NA children, it was discovered that many ED providers had an implicit preference for white children compared to those who identified as NA [45]. Indeed, racism and stigmatization are identified as being many American Indians’ experiences in healthcare.

One major cause of the disparity is that blacks are not offered revascularization services at the same rate as whites. Holman et al (2011: 425) write:

Finally, given that patients’ decisions are necessarily confined to the options offered by their physicians, racial differences in limb salvage care might be attributable to differences in physician decision making. There are some data to suggest lower vein graft patency rates in black patients compared to whites.18,19 A patient’s race, therefore, may influence a vascular surgeon’s judgment about the efficacy of revascularization in preventing or delaying amputation. Similarly, a higher proportion of black patients in our sample were of low SES, which correlates with tobacco use,20-22 and we know that continued tobacco use increases the risk of lower extremity graft failure approximately three-fold.23 It is possible that a higher proportion of black patients in our sample were smokers who refused to quit, in which case vascular surgeons would be much less likely to offer them the option of revascularization. While Medicare data include an ICD-9 diagnosis code for tobacco use, the prevalence in our study sample was approximately 2%, suggesting that this code was grossly unreliable as a means of directly measuring and adjusting for tobacco use.

Smoking, of course, could be a reason why revascularization would not be offered to black patients. Though, as I have noted, smoking ads are more likely to be found in lower-income neighborhoods which increases the prevalence of smokers in the community.

With this, I am reminded of two stories I have seen on television programs (I watch Discovery Health a lot—so much so that I have seen most of the programs they show).

In Untold Stories of the ER, a man came in with his hand cut off. He refused medical care. He would not let the doctors attempt to sew his hand back on. Upon the police entering his home to check for evidence (where his hand was found), they searched his computer. It seems that he had a paraphilia called “acrotomophilia” which is where one is sexually attracted to people with amputations. Although he wanted it to be done to himself—he had inflicted the wound on himself. After the doctor tried to reason with the man to have his hand sewed back on, the man would not let up. He did not want his hand sewed back on. I wonder if, years down the line, the man regretted his decision.

In another program (Mystery Diagnosis), a man had said that as a young boy, he had seen a single-legged war veteran amputee. He said that ever since then, he would do nothing but think about becoming an amputee. He lived his whole life thinking about it without doing anything about it. He then went to a psychiatrist and spoke of his desire to become an amputee. After some time, he eventually flew to Taiwan and got the surgery done. He, eventually, found happiness since he had done what he always wanted to.

While these stories are interesting they speak to something deep in the minds of the individuals who mutilate themselves or get surgery to otherwise healthy limbs.

Conclusion

Blacks are more likely than whites to receive amputations in affected limbs than whites and are less likely to receive treatments that may be able to save the affected limb (Holman et al, 2011; Hughes et al, 2013; Minc et al, 2017; Massada et al, 2018). Physician bias is a large driver of this. So, to better public health, we then must attempt to mitigate these biases that physicians have that lead to these kinds of disparities in healthcare. Medical and other kinds of racism have led to this disparity in amputations between blacks and whites. Thus, to attempt to mitigate this disparity, blacks must get the preventative care needed in order to save the affected limb and not immediately go for amputation. Thankfully, such disparities have been noticed and work is being done to decrease said disparities.

So race is a factor in the decision on whether or not to amputate a limb, and blacks are less likely to receive revascularization services.

Racism, Stress, and Physiology

1800 words

The term ‘racism’ has many definitions. What does it mean for a person to be a ‘racist’? What does it mean for a person to have ‘racist beliefs’? What does the term ‘racism’ refer to? The answers to these questions then will inform the next part—what does racism have to do with stress and physiology?

What is ‘racism’?

Racism has many definitions, so many—and so many for uses in different contexts—that it has been argued, for example by those in the far-right, that it is, therefore, a meaningless term. However, just because there are many definitions of the term, it does not then mean that there is no referent for the term we use. A referent is a thing that is signified. In this instance, what is the referent for racism? I will provide a few on-hand definitions and then discuss them.

In Part VI of The Oxford Handbook of Race and Philosophy (edited by Naomi Zack, 2016) titled Racisms and Neo-Racisms, Zack writes (pg 469; my emphasis):

Logically, it would seem as though ideas about race would have to precede racism. But the subject of racism is more broad and complicated than the subject of race, for at least these two historical reasons. First, the kind of prejudice (prejudged cognitions and negative emotions) and discrimination (treating people differently on the grounds of group identities) that constitute racism have a longer history than the modern idea of race, for instance in European anti-Semitism. And second, insofar as modern ideas of race have been in the service of the dominant interests in international and internal interactions, these ideas of race are ideologies that have devalued non-white groups. That is, ideas of race are themselves already inherently racist.

In philosophy, racism has been treated as attitudes and actions of individuals that affect nonwhites unjustly and social structures and institutions that advantage whites and disadvantage nonwhites. The first is hearts-and-minds or classic racism, for instance the use of stereotypes and harmful actions by whites against people of color, as well as negative feelings about them. The second is structural racism, for instance the use of stereotypes or institutional racism, for instance, the facts of how American blacks and Hispanics are, compared to whites, worse off on major measures of human well-being, such as education, income, family wealth, health, family stability, longevity, and rates of incarceration.

John Lovchik in his book Racism: Reality Built on a Myth (2018: 12) notes that “racism is a system of ranking human beings for the purpose of gaining and justifying an unequal distribution of political and economic power.” Note that using this definition, “hereditarianism” (the theory that individual differences between groups and individuals can be reduced to genes; I will give conceptual reasons why hereditarianism is false as what I hope is my final word on the debate) is a racist theory as it attempts to justify the current social hierarchy. (The reason why IQ tests were first brought to America and created by Binet and Simon; see The History and Construction of IQ Tests and The Frivolousness of the Hereditarian-Environmentalist IQ Debate: Gould, Binet, and the Utility of IQ Testing.) This is why hereditarianism saw its resurgence with Jensen’s infamous 1969 paper. Indeed, many prominent hereditarians have held racist beliefs, and were even eugenicists espousing eugenic ideas.

Headley (2000) notes a few definitions of racism—motivational, behavioral, and cognitive racism. Motivational racism is “the infliction of unequal consideration, motivated by the desire to dominate, based on race alone“; behavioral racism is “failure to give equal consideration, based on the fact of race alone”; and cognitive racism is “unequal consideration, out of a belief in the inferiority of another race.”

I have presented six definitions of racism—though there are many more. Now, for the purposes of this article, I will present my own: the ‘inferiorization’ of a racialized group which is then used to explain disparities in things like IQ test scores, social class/SES, education differences, personality, etc. Now, knowing what we know about physiological systems and how they react to the environment around them—the immediate environment and the social environment—how does this then relate to stress and physiology?

Racism, stress, and physiology

Now that we know what racism is, having had a rundown of certain definitions of ‘racism’, I will now discuss the physiological effects such stances could have on groups racialized as ‘races’ (note that I am using socialraces in this article; recall that social constructivists about race need to be realists about race).

The term ‘weathering’ refers to the body’s breaking down due to stress over time. Such stressors can come from one’s immediate environment (i.e., pollution, foodstuffs, etc) or their social environment (a demanding job, how one perceives themselves and how people react to them). So as the body experiences more and more stress it becomes more and more ‘weathered’ which then leads to heightened risk for disease in stressed individuals/populations.

Allostatic states “refer to altered and sustained activity levels of the primary mediators (e.g., glucocorticosteroids) that integrate energetic and associated behaviours in response to changing environments and challenges such as social interactions, weather, disease, predators and pollution” (McEwen, 2005). Examples of allostatic overload such as acceleration of atherosclerosis, hypertension (HTN), stroke, and abdominal obesity (McEwen, 2005) are more likely to be found in the group we racialize as ‘black’ in America—particularly women (Gillum, 1987; Gillum and Hyattsville, 1996; Barnes, Alexander, and Staggers, 1997; Worral et al, 2002; Kataoka et al, 2013).

Geronimus et al (2006) set to find out whether or not the heightened rate of stressors (e.g., racism, environmental pollution, etc) can explain why black bodies are more ‘weathered’ than white bodies. They found that such differences were not explained by poverty, indicating that it even affects well-off blacks. Allostatic load refers to heightened hormonal production in response to stressors. We know that physiological is homeodynamic and therefore changes based on the immediate environment and social environment (for example, when you feel like you’re about to get into a fight, your heart rate increases and you get ready to ‘fight or flight’).

Experiencing racism (environmental stimuli; real or imagined, the outcome is the same) is associated with increased blood pressure (HTN). So if one experiences racism they will them experience an increase in blood pressure, as BP is a physiological variable (Armstead et al, 1987; McNeilly et al, 1995; see Doleszar et al, 2018 for a review). The concept of weathering, then, shows that racial health disparities are, in fact, racist health disparities (Sullivan, 2015: 106). Racism, then, contributes to higher levels of allostasis and, along with it, higher levels of certain hormones associated with higher allostasis.

One way to measure biological age is by measuring the length of telomeres. Telomeres are found at the ends of chromosomes. Since telomere lengths shorten with age (Shammas, 2012), those with shorter telomeres are ‘biologically older’ than those of the same age with longer telomeres. Geronimus et al (2011) showed that black women had shorter telomeres than white women, which was due to subjective and objective stressors (i.e., racism). Black women in the age group 49-55 were 7.5 years ‘older’ than white women. Thus, they had an older physiological age compared to their chronological age. It is known that direct contact with discriminatory events is associated with poor health outcomes. Harrell, Hall, and Taliaferro (2003) note that:

“…physiological set points and the mechanisms governing them are not fixed. External stressors can permanently alter physiological functioning. Racism increases the volume of stress one experiences and may contribute directly to the physiological arousal that is a marker of stress-related diseases.

Social factors can, indeed, influence physiology and there is a wealth of information on how the social becomes biological and how environmental (social) factors influence physiological systems. Forrester et al (2019) replicated Geronimus’ findings, showing that blacks have a higher ‘biological age’ than whites and that psychosocial factors affect blacks more than whites. Simons et al (2020) also replicated Geronimus’ findings, showing that persistent exposure to racism was associated with higher rates of inflammation in blacks which then predicted higher rates of disease in blacks compared to whites. Such discrimination can help to explain differences in birth outcomes (e.g., Jasienska, 2009), stress, inflammation, obesity, stroke rates, etc in blacks compared to whites (Molnar, 2015).

But what is the mechanism by which higher allostatic load scores contribute to negative outcomes and shorter telomeres indicating a higher biological age? When one feels that they are being discriminated against, the sympathetic nervous system activates due to chronic stress and along with it HPA dysfunction. What this means is that there is a loss of the anti-inflammatory effects of cortisol—it becomes blunted. This then increases oxidative stress and inflammation. Thus, the inflammatory processes result in cardiovascular disease and immune and metabolic dysfunction. The HPA axis monitors and responds to stress—allostatic load. When stress hormones are released, the adrenal gland is targeted. When it receives a signal from the pituitary gland, it pumps epinephrine and norepinephrine into the body, causing our hearts to beat faster, causing us to breathe more deeply—what is known as ‘fight or flight.’ Cortisol is also released and is known as a stress hormone, but when the stressful event is over, all three hormones return to baseline. Thus, the higher amount of stress hormones in circulation indicates higher levels of allostatic load—higher levels of stress in the individual in question. We know that blacks have higher levels of allostatic load (i.e., stress-related hormones) than whites (Duru et al, 2012). Barr (2014: 71-72) writes:

Imagine, though, that before the allostatic load has a chance to return to its baseline level, another stressor is sensed by the hypothalamus. The allostatic load will once again increase to the plateau level. Should the perception of stressors be ongoing, the allostatic load will not have the chance to ever fully recharge, and the adrenal gland will be producing an ongoing stream of stress response hormones. The body will experience chronic elevation in its allostatic load. […] A person experiencing repeated stressors, without the opportunity for intervals that are relatively stress-free, will experience a chronically elevated allostatic load, with higher than normal levels of circulating stress response hormones.

Conclusion

What these studies show, then, is that race is a cause of health inequalities, but it’s not inherent in biology but due to social factors that influence the physiology of the individual in question. The term ‘racism’ has many referents, and using one of them identifies ‘hereditarianism’ as a racist ideology (it is inherently ideological). These overviews of studies show that racial health inequalities are due, in part, to perceived discrimination (racism) thus they are racist health disparities. We know that physiology is a dynamic system that can respond to what occurs in the immediate environment—even the social environment (Williams, 1992). Thus, what explains part of the health inequalities between races is perceived discrimination—racism—and how it affects the body’s physiological systems (HPA axis, HTN, etc) and telomeres.

My Citation Count

1200 words

I started this blog almost 5 years ago. Currently (excluding this one), there are 480 articles on this blog. Searching my blog name “notpoliticallycorrect.me” on Google Scholar leads to two citations—one on “IQ” and obesity and the other on inclusionism about race when it comes to medicine. These two cites pretty much perfectly show my views and their change in the past 5 years since the creation of this blog. I will discuss both papers that cited me in turn.

In the journal Social and Human Sciences. Domestic and Foreign Literature (a sociology journal), a 2016 article I published (back in my “HBD” days titled “Race, Obesity, Poverty, and IQ, writing:

income and education (which in the latter case presumably correlates with IQ levels). They have the highest prevalence of type 2 diabetes. In terms of ethnicity, overweight indicators are as follows: 67.3% for whites, 75.6% for African Americans and 77.9% for Latinos. Summing up all this, we obtain, in the words of the authors of the study, “politically incorrect conclusions”: African Americans and Hispanics are more at risk of living in poverty, have lower IQ, higher rates of obesity and a chance of developing diabetes; The main factor in these correlations is the IQ level (Race, obesity, poverty and IQ, 2016).

Almost four years later (after my views have undergone a significant change) I would draw different conclusions. Blacks are 51% more likely to be obese than whites (Lincoln, Abdou, and Lloyd, 2016) with the cause being a multitude of factors. Though it seems that black American men with more African ancestry may be protected against central adiposity (Klimentidis et al, 2016). Racial disparities in obesity are due to an interaction of a multitude of factors (Byrd, Toth, and Stanford, 2018). Interestingly, black kids with obesity don’t perceive themselves as obese (Lankarani and Assani, 2018), which, presumably, is due to higher rates of obesity in the black population. Black girls are more likely to have an earlier menarche than white giris (e.g., Freedman et al, 2000) and it is because black girls are more likely to be obese than white girls which is due to the effects of leptin being permissive for menarche, from the higher levels of body fat in black girls (Salsberry, Reagen, and Pajer, 2010).

We must look to social determinants of health to understand why certain non-white populations are more likely to be obese than others. Looking at “IQ” as causal for obesity—which I used to believe—obscures much more than it helps. We can look to epigenetic effects, for example, regarding biological explanations of obesity (Krueger and Reithner, 2016), for instance high BMI in black women being related to saliva-based DNA methylation, which is used as a marker for aging (Li et al, 2019). Even perceived racism (it does not have to be actual) can have physiologic effects on black women, heigtening cortisol levels, leading to a heigtened obesity risk (Mwendwa et al, 2016).

In any case, it’s cool that I got cited but uncool that it was something that I don’t believe anymore.

The second citation comes from Rossi (2020: 13) in the journal Social Science Information titled New avenues in epigenetic research about race: Online activism around reparations for slavery in the United States citing my article Race, Medicine, and Epigenetics: How the Social Becomes Biological:

Consequently, social scientists’ opinions about epigenetic research dealing with race and slavery have sometimes been scrutinized by blog authors. For example, the article untitled [sic] ‘Race, medicine, and epigenetics: How the social becomes biological’ published in 2019 on the blog Notpoliticallycorrect features a long discussion on whether race could be seen as a viable variable to discuss the epigenetics of trauma, especially relating to slavery in the US.14 After summarizing the views of legal scholar and sociologist Dorothy Roberts, who has argued repeatedly in her works against the use of the concept of race in biomedical sciences, the author sides with philosophers Michael Hardimon and Shannon Sullivan, who are both enthusiastic about the inclusion of race to discuss genetics and epigenetics:

Race and medicine is a tendentious topic. On one hand, you have people like sociologist Dorothy Roberts (2012) who argues against the use of race in a medical context, whereas philosopher of race Michael Hardimon thinks that we should not be exclusionists about race when it comes to medicine. If there are biological races, and there are salient genetic differences between them, then why should we disregard this when it comes to a medically relevant context? [. . .] So, we should not be exclusionists (like Roberts), we should be inclusionists (like Hardimon). [. . .] Furthermore, acknowledging the fact that the social dimensions of race can help us understand how racism manifests itself in biology (for a good intro to this see Sullivan’s (2015) book The Physiology of Racist and Sexist Oppression, for even if the ‘oppression’ is imagined, it can still have very real biological effects that could be passed onto the next generation – and it could particularly affect a developing fetus, too). It seems that there is a good argument that the effects of slavery could have been passed down through the generations manifesting itself in smaller bodies.

Relying also on Jasienska’s research, the author of this blog post therefore dismissed the idea that race should not be applied to the medical field, while using the words and legitimacy of humanities scholars such as Hardimon and Sullivan to back up their claims. These contributions show the way journalists and various blog authors write about epigenetics by mixing together scientific articles in various fields (the social sciences, philosophy, psychiatry, social work) in an effort to bring more legitimacy to the topic. This process highlights the ways in which lay circles produce new connections between various papers and texts dealing with epigenetics, no matter how different their fields of expertise may be.

This shows a very sharp contrast with my current views and my older views on race and obesity. Before, thinking that obesity was “determined” by IQ (e.g., Kanazawa, 2012; Kanazawa, 2014) was an error—people with low “IQs” are more likely to be in poverty and have less access to good foods, along with the abundance of fast food restaurants in areas with a higher concentration of blacks (James et al, 2014). Black women, for instance, have a lower RMR than white women (Gannon, DiPietro, and Poehlman, 2000)

These two articles of mine that were cited (on similar issues, no less) show the evolution of my views over the past four or so years in between the publication of the two articles on this blog. This is a good case study on how the one can view the aetiology of one thing completely different based on the types of views they previously held. The views of obesity and race I hold now are much more complex than the reductive “it’s genes/IQ” kind of guy that I used to be. A more holistic view of obesity disparities, factoring in access to food (food swamps/deserts), income, location etc is more informative than looking just to “IQ” or “genes for” obesity—because even if “genes for” obesity exist and even if “genes for” obesity are distributed unevenly across races, the predominant determinant of weight will be activity level/caloric consumption, which is based on SES and other factors—not “IQ” or “obesity genes.” The social does become biological, and it does have consequences for obesity disparities between and within races.

“Mongoloid Idiots”: Asians and Down Syndrome

1700 words

Look at a person with Down Syndrome (DS) and then look at an Asian. Do you see any similarities? Others, throughout the course of the 20th century have. DS is a disorder arising from chromosomal defects which causes mental and physical abnormalities, short stature, broad facial profile, and slanted eyes. Most likely, one suffering from DS has an extra copy of chromosome 21—which is why the disorder is called “trisomy 21” in the scientific literature.

I am not aware if most “HBDers” know this, but Asians in America were treated similarly to blacks in the mid-20th century (with similar claims made about genital and brain size). Whites used to be said to have the biggest brains out of all of the races but this changed sometime in the 20th century. Lieberman (2001: 72) writes that:

The shrinking of “Caucasoid” brains and cranial size and the rise of “Mongoloids” in the papers of J. Philippe Rushton began in the 1980s. Genes do not change as fast as the stock market, but the idea of “Caucasian” superiority seemed contradicted by emerging industrialization and capital growth in Japan, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Singapore, and Korea (Sautman 1995). Reversing the order of the first two races was not a strategic loss to raciocranial hereditarianism, since the major function of racial hierarchies is justifying the misery and lesser rights and opportunities of those at the bottom.

So Caucasian skulls began to shrink just as—coincidentally, I’m sure—Japan began to get out of its rut it got into after WWII. Morton noted that Caucasians had the biggest brains with Mongoloids in the middle and Africans with the smallest—then came Rushton to state that, in fact, it was East Asians who had the bigger brains. Hilliard (2012: 90-91) writes:

In the nineteenth century, Chinese, Japanese, and other Asian males were often portrayed in the popular press as a sexual danger to white females. Not surprising, as Lieberman pointed out, during this era, American race scientists concluded that Asians had smaller brains than whites did. At the same time, and most revealing, American children born with certain symptoms of mental retardation during this period were labeled “mongoloid idiots.” Because the symptoms of this condition, which we now call Down Syndrome, includes “slanting” eyes, the old label reinforced prejudices against Asians and assumptions that mental retardation was a peculiarly “mongoloid” racial characteristic.

[Hilliard also notes that “Scholars identified Asians as being less cognitively evolved and having smaller brains and larger penises than whites.” (pg 91)]

So, views on Asians were different back in the 19th and 20th centuries—it even being said that Asians had smaller brains and bigger penises than whites (weird…).

Mafrica and Fodale (2007) note that the history of the term “mongolism” began in 1866, with the author distinguishing between “idiotis”: the Ethiopian, the Caucasian, and the Mongoloid. What led Langdon (the author of the 1866 paper) to make this comparison was the almond-shaped eyes that DS people have as well. Though Mafrica and Fodale (2007: 439) note that it is possible that other traits could have forced him to make the comparison, “such as fine and straight hair, the distribution of apparatus piliferous, which appears to be sparse.” Mafrica and Fodale (2007: 439) also note more similarities between people with DS and Asians:

Down persons during waiting periods, when they get tired of standing up straight, crouch, squatting down, reminding us of the ‘‘squatting’’ position described by medical semeiotic which helps the venous return. They remain in this position for several minutes and only to rest themselves this position is the same taken by the Vietnamese, the Thai, the Cambodian, the Chinese, while they are waiting at a the bus stop, for instance, or while they are chatting.

There is another pose taken by Down subjects while they are sitting on a chair: they sit with their legs crossed while they are eating, writing, watching TV, as the Oriental peoples do.

Another, funnier, thing noted by Mafrica and Fodale (2007) is that people with DS may like to have a few plates across the table, while preferring foodstuffs that is high in MSG—monosodium glutamate. They also note that people with DS are more likely to have thyroid disorders—like hypothyroidism. There is an increased risk for congenital hypothyroidism in Asian families, too (Rosenthal, Addison, and Price, 1988). They also note that people with DS are likely “to carry out recreative–reabilitative activities, such as embroidery, wicker-working ceramics, book-binding, etc., that is renowned, remind the Chinese hand-crafts, which need a notable ability, such as Chinese vases or the use of chop-sticks employed for eating by Asiatic populations” (pg 439). They then state that “it may be interesting to know the gravity with which the Downs syndrome occurs in Asiatic population, especially in Chinese population.” How common is it and do they look any different from other races’ DS babies?

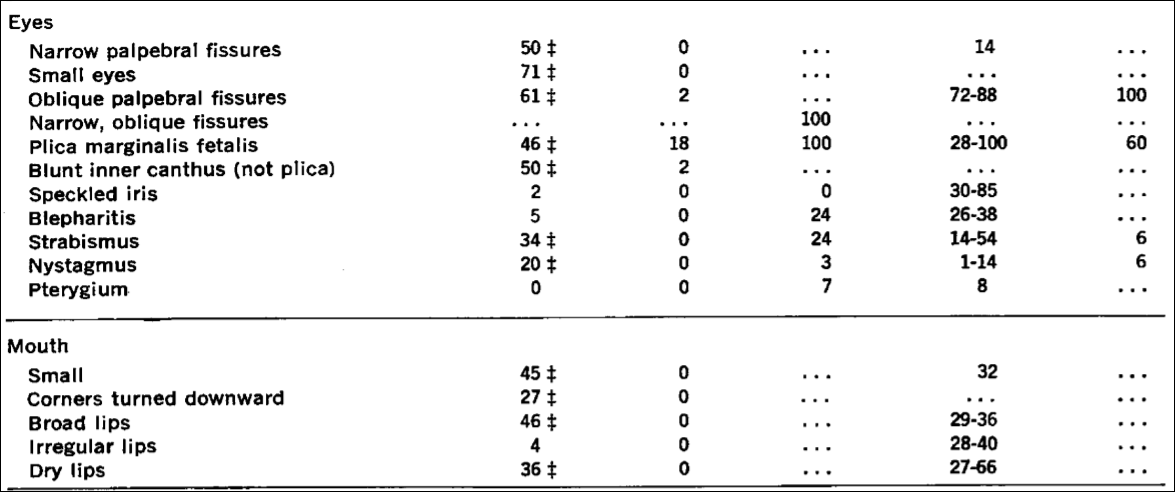

See, e.g., Table 2 from Emanuel et al (1968):

Emanuel et al (1968: 465) write that “Almost all of the stigmata of Down’s syndrome presented in Table 2 appear also to be of significance in this group of Chinese patients. The exceptions have been reported repeatedly, and they all probably occur in excess in Down’s syndrome.”

Examples such as this are great to show the contingencies of certain observations—like with racial differences in “intelligence.” Asians, today, are revered for “hard work”, being “very intelligent” and having “low crime rates.” But, even as recently as the mid 20th century—going back to the mid 18th century—Asians (or Mongoloids, as Rushton calls them) were said to have smaller brains and larger penises. Anti-miscegenation laws held for Asians, too of course, and so interracial marriage was forbidden with Asians and whites which was “to preserve the ‘racial integrity’ of whites” (Hilliard, 2012: 91).

Hilliard (2012) states that the effeminate, small-penis Asian man. Hilliard (2012: 86) writes:

However, it is also possible that establishing the racial supremacy of whites was not what drove this research on racial hierarchies. If so, the IQ researchers were probably justified in protesting their innocence, at least in regard to the charge of being racial supremacists, for in truth, the Asians’ top ranking might have unintentionally underscored that true sexual preoccupations underlying this research in the first place. It not seems that the real driving force behind such work was not racial bigotry so much as it was the masculine insecurities emanating from the unexamined sexual stereotypes still present within American popular culture. Scholars such as Rushton, Jensen, and Herrnstein provided a scientific vocabulary and mathematically dense charts and graphs to give intellectual polish to the preoccupations. Thus, it became useful to tout the Asians’ cognitive superiority but only so long as whites remained above blacks in the cognitive hierarchy.

Of course, by switching the racial hierarchy—but keeping the bottom the same—IQ researchers can say “We’re not racists! If we were, why would we state that Asians were better on trait T than we were!”, as has been noted by John Relethford (2001: 84) who writes that European-descended researchers “can now deflect charges of racism or ethnocentrism by pointing out that they no longer place themselves at the top. Lieberman aptly notes that this shift does not affect the major focus of many ideas regarding racial superiority that continue to place people of recent African descent at the bottom.” While biological anthropologist Fatima Jackson (2001: 83) states that “It is deemed acceptable for “Mongoloids” to have larger brains and better performance on intelligence tests than “Caucasoids,” since they are (presumably) sexually and reproductively compromised with small genitalia, low fertility, and delayed maturity.”

The main thesis of Straightening the Bell Curve is that preoccupations with brain and genital size is a driving part of these psychologists who study racial differences. Stating that Asians had smaller penises but larger heads though they were less likely to like sex while blacks had larger penises, smaller heads and were more likely to like sex while whites were, like Goldilocks, juuuuuust right—a penis size in-between Asians and blacks and a brain neither too big or too small. So, stating that X race had smaller brains and bigger penises seems, as Hilliard argues, to be a coping mechanism for certain researchers and to drive women away from that racial group.

In any case, how weird it is for Asians (“Mongoloids”) to be ridiculed as having small brains and large penises (a hilarious reversal of Rushton’s r/K bullshit) and then—all of a sudden—for them to come out on top over whites while whites are still over blacks in this racial hierarchy. How weird is it for the placements to change with certain economic events in a country’s history. Though, as many authors have noted, for instance Chua (1999), Asian men have faced emasculinazation and femininzation in American society. So, since they were seen to be “undersexed, they were thus perceived as minimal rivals to white men in the sexual competition for women” (Hilliard, 2012: 87).

So, just like the observation of racial/country IQ are contingent on the time and the place of the observation, so too is the observation of racial differences in certain traits and how they can be used for a political agenda. As Constance Hilliard (2012: 85) writes, referring to Professor Michael Billig’s article A dead idea that will not lie down (in reference to race science), “… scientific ideas did not develop in a vacuum but rather reflected underlying political and economic trends.“ And so, this is why “mongoloid idiots” and undersexed Asians appeared in American thought in the mid-20th century. So these ideas noted here—mongloidism, undersexed Asians, small penis, large penis, small brain, large brained Asians (based on the time and the place of the observation) show, again, the contingency of these racial hierarchies—which, of course, still stay with blacks on the bottom and whites above them. Is it not strange that whites moved a rung down on this hierarchy as soon as Rushton appeared in the picture? (Since, Morton noted that they had smaller heads than Caucasians, Lieberman, 2001.)

The origins of the term “mongloidism” are interesting—especially with how they tie into the origins of the term Down Syndrome and how they related to the “Asian look” along with all of the peculiarities of people with DS and (to Westerners), the peculiarities of Asian living. This is, of course, why one’s political motives, while not fully telling of their objectives and motivations, may—in a way—point one in the right direction as to why they are formulating such hypotheses and theories.

Race/Ethnicity and Pain

1700 words

There are many superficial physical differences between the races. But differences in pain sensitivity would be one that is not really “superficial”, as you can’t really see it (you can see someone’s reaction to pain, but not see it). “Pain” is defined as physical discomfort caused by injury. There are some myths about pain differences between racial groups, that still persist today. And these myths have bad consequences.

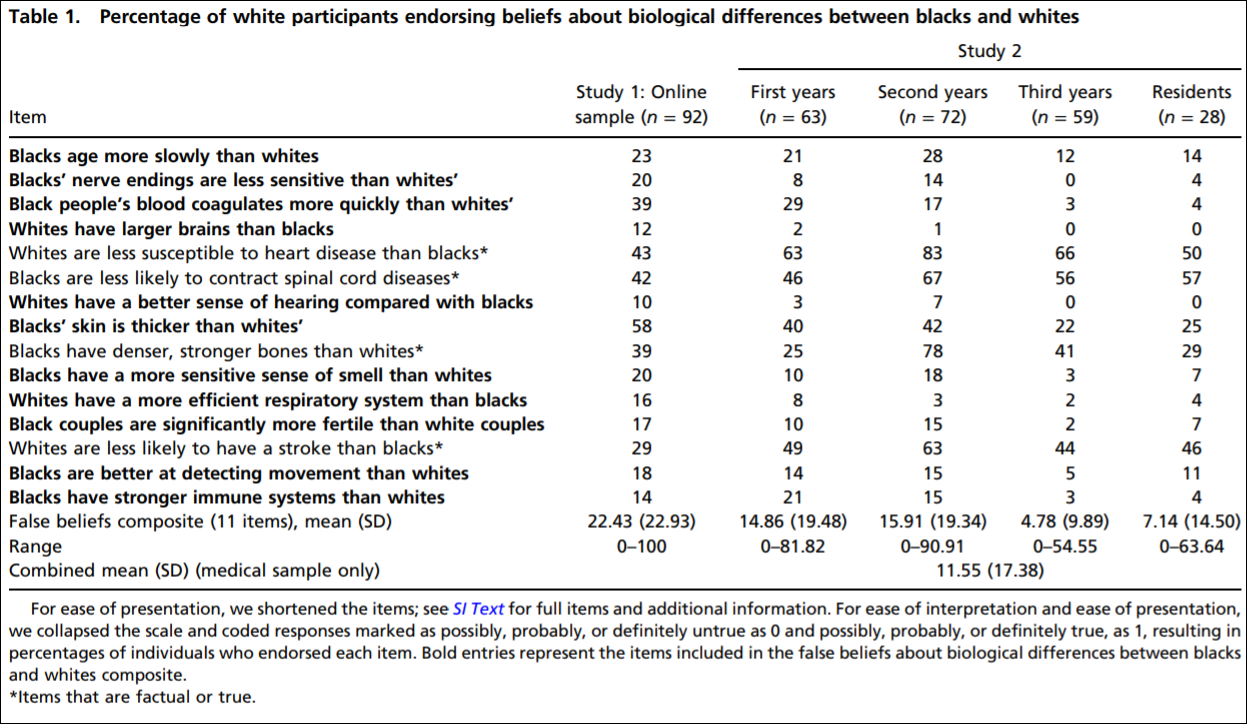

For example, Hoffman et al (2016) state that “people assume a priori that blacks feel less pain than do whites.” Hoffman et al (2016) carried out two studies: (1) using a between-participants design, laymen were asked to assess the pain of white and black subjects and (2) again using a between-participants design, they asked students and medical doctors to assess pain between blacks and whites. In (2) they asked these 15 questions:

1. On average, Blacks age more slowly than Whites.

2. Black people’s nerve-endings are less sensitive than White

people’s nerve-endings.

3. Black people’s blood coagulates more quickly–because of

that, Blacks have a lower rate of hemophilia than Whites.

4. Whites, on average, have larger brains than Blacks.

5. Whites are less susceptible to heart disease like hypertension than Blacks.

6. Blacks are less likely to contract spinal cord diseases like

multiple sclerosis.

7. Whites have a better sense of hearing compared with Blacks.

8. Black people’s skin has more collagen (i.e., it’s thicker) than

White people’s skin.

9. Blacks, on average, have denser, stronger bones than Whites.

10. Blacks have a more sensitive sense of smell than Whites;

they can differentiate odors and detect faint smells better

than Whites.

11. Whites have more efficient respiratory systems than Blacks.

12. Black couples are significantly more fertile than White couples.

13. Whites are less likely to have a stroke than Blacks.

14. Blacks are better at detecting movement than Whites.

15. Blacks have stronger immune systems than Whites and are

less likely to contract colds.

(I’ll cover these questions in a future article.)

Here is the table showing the respondents’ answers to the questions:

So they established that whites with no medical training hold false beliefs about black-white differences that then carry over to pain management. They showed in study 2 that medical students’ and residents’ apparently false beliefs about racial differences in the questions they answered showed bias in the accuracy of the recommended pain treatments. Hoffman et al (2016) conclude that:

The present work sheds light on a heretofore unexplored source of racial bias in pain assessment and treatment recommendations within a relevant population (i.e., medical students and residents), in a context where racial disparities are well documented (i.e., pain management). It demonstrates that beliefs about biological differences between blacks and whites—beliefs dating back to slavery—are associated with the perception that black people feel less pain than do white people and with inadequate treatment recommendations for black patients’ pain.

(See also the Psychology Today article on the matter.)

Similarly, Hollingshead et al (2016) reported that subjects, regardless of race, rated the white person more sensitive to pain and more likely to report pain than the black person. Whites reported that they were less pain sensitive and less likely to report pain than their peers. Blacks reported that they were more sensitive to pain while reporting more pain than their peers.

Interestingly, Trawalter, Hoffman, and Waytz (2012) state that black NFL players are more likely to play in a subsequent game than whites when injured, and that, as found in many other studies, blacks are more likely to feel less pain than whites. However, what the literature really shows is the opposite: blacks are more likely to feel pain than whites.

Kim et al (2017) showed that blacks, “Hispanics” and Asians had lower pain tolerance, higher pain ratings and greater temporal sensation of pain. They also showed that blacks had lower pain tolerance and higher pain ratings but no differences in pain threshold.

Blacks report greater pain regarding AIDs, glaucoma, migraine, headache, jaw pain, postoperative pain, joint pain and many other types of pain compared to whites (Green et al, 2003; Klonoff, 2009). Riley III et al’s (2002) results indicate that blacks show a stronger link between pain and emotions than whites. Obana and Davis (2016) showed that Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander male and females reported higher pain scores than whites when it came to joint pain (but they were not significant). Bolen et al (2010) showed that work limitation, severe joint pain, and arthritis-attributable activity were higher for non-“Hispanic” blacks, “Hispanics” and multiracial people compared to non-“Hispanic” whites. Even American Indians, Alaskan natives, and Aboriginal Canadians had a higher prevalence of pain and pain symptoms than Americans (Jimenez et al, 2011).

Chan et al (2011) surveyed older Singaporeans. They found that Malay people had lower pain sensitivity compared to Chinese people, and that Indians reported greater pain sensitivity when compared with Malay and Chinese people. Australian women rated menstrual pain higher and lasting 36 percent longer than Chinese women (Zhu et al, 2010).

When it comes to potential mechanisms, physiological mechanisms are hypothesized by Campbell and Edwards (2012) who write:

For example, in comparison to non-Hispanic whites, African–Americans have reduced nociceptive flexion reflex thresholds [26]; the nociceptive flexion reflex is an electrophysiological, spinally mediated reflex, which is not amenable to voluntary control or subject to issues of response bias that plague self-report of pain experiences. This finding suggests that the observed ethnic differences in pain are unlikely to be fully explainable by sociocultural influences and hints that neurobiological processes may contribute to such differences.

Mossey (2011) shows that “Racial/ethnic minorities consistently receive less adequate treatment for acute and chronic pain than non-Hispanic whites, even after controlling for age, gender, and pain intensity.” Martinez et al (2014) showed that when it comes to colorectal and lung cancer, mixed-race individuals and blacks are more likely to report higher pain severity than whites. (Also see Shavers, Bakos, and Sheppard, 2010.)

All of the literature points in the opposite direction of the myths about pain sensitivity in regard to race: blacks feel more pain than whites and are more likely to have a lower pain tolerance. So the myths people hold about differences in pain between racial groups (mostly blacks and whites) are false. Pain is a subjective experience. And there will be differences in pain thresholds between individuals and racial groups and the causes may be both sociocultural and physiological in nature. However, this bias (in the wrong direction) speaks to what I wrote about last night: physician bias when it comes to blacks and other minorities.

Barr (2014: 183-184) writes:

Based to a certain extent on the attention given to his earlier publication, Todd moved to a faculty position with the Emory University School of Medicine, in Atlanta, Georgia. There he was able to essentially repeat his earlier study, this time examining persons coming tothe emergency room of a large, inner-city community hospital in Atlanta that was affiliated with Emory (Todd et al, 2000). He evaluated the medical records of 217 individuals coming to the emergency room over a 40-month period for treatment of an isolated long-bone fracture. Given the racial makeup of Atlanta, these included 127 blacks and 90 whites. They found that

- 54 of the blacks (43 percent) received no medication for pain during their treatment

- 23 of the whites (26 percent) received no medication for pain during their treatment

As with the earlier study in Los Angeles involving whites and Hispanics, in this study, the blacks were nearly twice as likely to receive no pain medication while in the emergency room. With this study, the authors were keenly aware of the importance of documenting the extent to which the patients expressed painful symptoms. By thoroughly reviewing the medical records of these patients, they found that 54 percent of blacks and 59 percent of whites had a notation in their medical record that they had expressed painful symptoms. The nearly twofold difference in withholding pain medication in blacks and whites was because the doctor didn’t order the medication, not because the patient didn’t want the medication.

This, again, speaks to physician bias when it comes to race in a medical context. Race is a useful tool in medicine, but to hold biases in the complete opposite direction that they exist in is wrong. This study—and many others—speak to the type of bias that physicians have against minorities in a medical context. Understanding that the differences in pain are actually the opposite from what is commonly believed by both laypeople and medical doctors is important: if blacks feel more pain than whites regarding the same injuries and they are not getting the care needed, then this speaks to physician bias. What Barr showed was that blacks were treated at the emergency room based on their ethnicity. This is wrong. Race/ethnicity is a useful tool in medicine, but to outright use it as an assumption for numerous factors makes no sense and could cause more harm than good.

Using race in a medical context is a good thing. But using race in a medical context using essentialist, outdated views about race is wrong and can lead to many horrible outcomes. Of course, using race in this context can and does lead to certain things being discovered over others. For instance, if one’s race is assumed to be “driving” one’s illness (i.e., that one has a disease that that race/ethny is more likely to have), then race can and is a good marker to use—specifically geographic ancestry. However, when it comes to things like pain management, this obviously leads to false ideas about how different groups manage and feel pain.

Views about racial differences in pain affect both laypeople and medical doctors. These views can be and are harmful. The literature points to the case being the opposite of what is believed by people: blacks have lower pain tolerance and higher pain ratings than whites. These types of differences are also found between many other races and ethnic groups. The causes could be both sociocultural and physiological. A person’s response to pain depends on their unique physiology, life experiences, ethnicity and other factors. Understanding how and why physicians are biased toward how blacks feel pain is important, along with addressing the other biases that they have about other minorities when it comes to a medical context. Race and ethnicity are important tools for medicine, but these are some of the ways that the concepts can be used with nothing good coming out of it.

Health by State and Racial Discrimination by Physicians

3000 words

I’m currently reading Health Disparities in the United States: Social Class, Race, Ethnicity and Health by medical doctor and sociologist Donald Barr. In the book, he chronicles differences in health between races and ethnies, talks about the concepts of race used and cites well-known studies to people who read this blog, and he also shows that doctors are—either conscious or not—biased against minorities in certain medical contexts.

In Chapter 1 discusses the fact that, although Americans spend the most money on health care, Americans have a lower life expectancy and higher infant mortality rate than all other developed countries, showing the association in social inequality and health across all income levels and education. In Chapter 2, he asks the question “What is health?”, discussing many concepts of what “health” is. In Chapter 3, he defines “socioeconomic status” and shows the link between poor health and poor SES. In Chapter 4, he discusses the link between inequality and poor health, introducing the concept of “allostatic load”, which is the physiologic response to being in a spot of social disadvantage.

In Chapter 5, he looks at different race concepts, since it is a main premise of the book. In Chapter 6, he shows that minorities are more likely to be in a position of low SES. He asks, if minorities of the same SES as whites are consistently found to be of lower health than whites of the same SES, is it because those with poor health tend to be minorities, that they tend to have lower SES or both? In Chapter 7, he asks the same questions while focusing on children. In Chapter 8, he examines disparities in access to healthcare, showing that even when minorities have the same insurance and doctors that minorities still face worse health outcomes (he shows that they either do not receive appropriate healthcare or receive lower-quality care). In Chapter 9, he shows that physicians treat blacks and other minorities differently, albeit unconsciously. In Chapter 10, he discusses when—if ever—a physician would be justified in using racial/ethnic categories. And in Chapter 11, he states that not all of these disparities need to be eliminated.

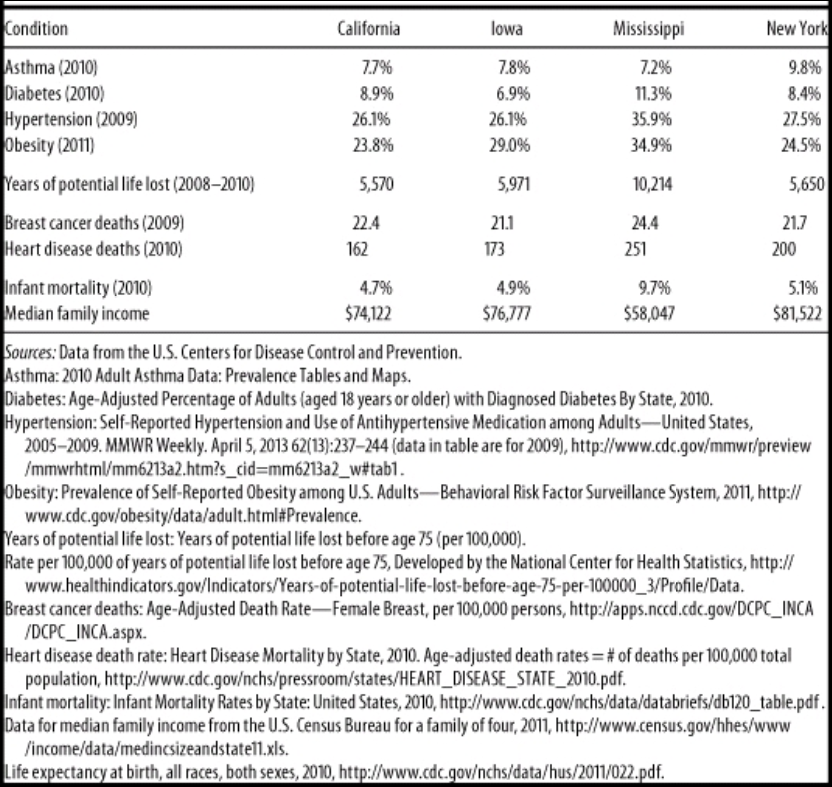

In Chapter 2, Barr (2014: 45) presents this table, showing rates of illness and selective rates of death between States in America. Obviously, the one to look at that is different than the others is Mississippi. Mississippi is 37.5% black.

Wow, I wonder why Mississippi has such a high rate of obesity, diabetes, and hypertension (high blood pressure). Must be all of those obesity, diabetes and hypertension genes (HBDer).

Obesity and diabetes

The first thing to look at is median income. It is substantially lower in Mississippi compared to California, Iowa, and New York. About 23 million people in America live one mile from a supermarket, while black Americans are about half as likely to have access to supermarkets while “Hispanics” are about a third likely to have access to them (New York Law School Racial Justice Project, 2012). So when it comes to those who have to travel more than a mile for fresh fruit and vegetables, they have poorer health (Stack, 2015). So combine lower median income, along with food deserts and one can start to see how minorities have poorer health due in part to their SES. In short, living in a food desert can affect public health.

Blacks are the most obese ethnic group in America, and this relationship is largely driven by black women. Now, it’s not weird that women have higher levels of body fat than men, since women it is needed for physiological functioning. Though, there is something weird here: Black American men with more African ancestry are less likely to be obese (Klimentidis et al, 2016). Since black women and black men in America are in the same economic bracket, there must be something in the West African male physiology that “protects” them against central adiposity, though variation in social, environmental and cultural factors may play a role as well. In any case, the more West African ancestry American blacks have, the less likely they are to be obese. Klimentidis et al’s (2016) study “suggests that there are specific genetic variants and physiological mechanism(s) that differ among West African and European populations.”

Obesity affects more ethnies in America than others: non-Hispanic blacks and “Hispanics” are more likely to be obese than non-“Hispanic” whites and Asians (Hales et al, 2017). This could be due to, in part, to the variation in supermarket access and access to good foods—the concept of food deserts. Look at any low-income area near you. You’ll see a majority of corner stores with cheap, garbage food. The lack of ability to buy good food (along with the education to know what to buy and when to buy it) can explain differences in obesity rates—obviously not all. Obesity is related with diabetes, and sinec the relationship is so strong, the term “diabesity” was coined.

Eating cheap, processed carbohydrates spikes insulin. Repeated insulin spikes over time leads to type II diabetes and, eventually, obesity too. One can be skinny and have diabetes (a phenomenon known as thin on the outside, fat on the inside “TOFI”). However, since both diseases are co-morbid, we need to look at them in similar contexts. The higher rates of obesity can help to explain the higher rates of diabetes and hypertension—since those who are obese have higher blood pressure (Aronow, 2017).

Minorities are more likely to develop type II diabetes (Tuchman, 2011), and the cause of this is access to high-quality foods. But racial differences in obeisty and SES do not fully explain the higher rates of type II diabetes in black Americans; being a black American is a strong, independent factor for developing type II diabetes and this is compounded by low SES (Brancati et al, 1996). Zizi et al (2016) showed that both long and short black sleepers have an increased risk of developing type II diabetes. There are racial differences in sleep, with blacks having higher durations of long and short sleep compared to whites (Adenekan et al, 2013).

Hypertension

Now let’s look at hypertension (blood pressure). Blood pressure is a physiological variable. Since it is a physiological variable, it can and does respond to social/environmental contexts. So blood pressure can be affected by social contexts, too. For example, Williams (1992) cites stress, socioecologic stress, social support, coping patterns, health behavior, sodium and more for reasons why blacks have higher BP than whites. Dressler (1991) shows that the struggle to maintain a middle-class lifestyle is related to higher levels of BP. Similarly, Keith and Herring (1991) show that skin color is a strong predictor of occupational status and that darker-skinned blacks in America are twice as likely to experience racial discrimination than lighter-skinned blacks. This, too, can help to account for higher levels of BP between the races. In any case, Williams (1992) shows, definitively, that the causes of black-white differences in BP lie in the social environment.

Similarly, Non, Gravlee, and Mulligan (2012) show that racial disparities in BP are explained by education, and not genetic ancestry. They show that the association between BP and education was much stronger for blacks than for whites. Their results also support “the minority poverty hypothesis because the worst blood pressures were predicted for people who faced the double burden of being less educated and identifying as African American.” People who face discrimination could, and do, have higher levels of BP due to the stress they feel due to the discrimination. (Note that I take no sides on whether the discrimination is real or imagined, because even if it were imagined, it still leads to real physiologic consequences.)

Do note that there is a just-so story to explain how and why blacks have higher levels of blood pressure than whites: The Slavery Hypertension Hypothesis (Lujan and Dicarlo, 2018). This has all of the hallmarks of a just-so story posited by evolutionary psychologists. The story goes like this: Black slaves who were on the way to America in the Middle Passage had genes that favored better salt retention. So it is noted that black Americans have higher rates of BP than whites, and then they work backward and attempt to posit the best story possible to explain the current-day observation. This is the usual method evolutionary psychologists use—the method of reverse engineering, the inference from function to cause. So (1) note that blacks have higher levels of BP than whites; (2) infer the function to cause (blacks with genes that favored salt retention were more likely to survive; so (3) this is why blacks have higher rates of BP than whites. Though the explanation fails, since education, and not genetic ancestry, explains the difference in BP between blacks and whites (Non, Gravlee, and Mulligan, 2012). One only needs to understand the intricacies of physiology and how our physiological systems respond to what occurs in the greater environment.

So, obesity can explain both the higher rates of diabetes and higher rates of blood pressure, with differences in the immediate social environment explaining the rest of the differences in blood pressure between blacks and whites. (Note that heart disease deaths are directly related to hypertension. Heart disease affects blacks more than whites.)

Breast cancer

In Race, Medicine, and Epigenetics: How the Social Becomes Biological, I shortly discussed breast cancer in black women:

Black women are more likely to die from breast cancer, for example, and racism seems like it can explain a lot of it. They have less access to screening, treatment, care, they receive delays in diagnoses, along with lower-quality treatment than white women. But “implicit racial bias and institutional racism probably play an important role in the explanation of this difficult treatment” (Hardimon, 2017: 166). Furthermore, black women are more than twice as likely to acquire a type of breast cancer called “triple negative” breast cancer (Stark et al, 2010; Howlader et al, 2014; Kohler et al, 2015; DeSantis et al, 2019). Of course, this could be a relevant race-related genetic difference in disease.

Infant mortality

Now note the infant mortality rate between the states: the infant mortality rate in Mississippi is 9.7%. Smith et al (2018) show that black women are at a higher rate of having their infant die at birth. Pre-term births are related to low birth weights, and they both are related to infant mortality. Matoba and Collins (2017) write:

In the United States, African-American infants have significantly worse infant mortality than white infants. Individual risk factors alone do not explain this persistent gap, just as they did not explain the disparity in preterm birth and low birth weight. Recent studies in social determinants provide insight into the contribution of community and environmental factors to the racial disparity. Select community-level factors are potential, but partial, determinants of the racial disparity. Interpersonal and institutionalized racism is an important, and increasingly recognized, stressor for African-American women with damaging consequences to maternal and child health.

The Guardian ran a recent story on infant mortality and race, positing racism as a cause of the disparity. In any case, the social environment can and does play a part in everything discussed here today since the social can and does become biological. Part of the reason why Mississippi has a way higher rate of years of potential life lost (10,214 compared to 5500-5900 for Iowa, New York, and California) is that rates of infant mortality are higher in Mississippi. So the median age of death is 75. If an infant dies at one year of age, then that is 74 years of life lost. Therefore it is not surprising that the State with the highest level of infant mortalities has a higher number of years of potential life lost. Further, one 2017 review found that segregation was associated with increased risk of preterm birth and low birth weight for blacks (Mehra, Boyd, and Ickovis, 2017)

Note how Mississippi has lower rates of asthma. This is explained by the fact that Mississippi is more rural than, say New York. Rates of asthma are associated with living in a metropolitan area (Frazier et al, 2012; Malik, Kumar, and Frieri, 2012). (Note that blacks and other races have higher rates of asthma than other races.)

Physician bias

The lower one’s position is on the social hierarchy the lower their probability of staying healthy and having a high life expectancy; when people have the same type of health insurance and are treated for the same disease in the same hospital by the same doctor, that minority groups get worse health care, either not receiving it or receiving lower standards of quality in care. What could account for such disparities? I asked PumpkinPerson the question, and he said:

1) EGI: Doctors put more effort into saving coethnics: she looks like my italian grandma. I’ll make sure she gets the best medicine.

2) IQ: low IQ populations don’t understand the doctor’s advice and damage their health

3) r/K: some populations have faster life history so don’t live as long, even with good medical care

If (1), then the doctors need to be named, shamed, and have their medical licenses revoked. If (2), then they need better education (since IQ is just an index of middle-class knowledge). (3) is completely irrelevant, since it doesn’t make sense for humans and the concept is long-dead in ecology. In any case, PumpkinPerson danced around the true cause: differences in healthcare brought about by unconscious bias (of which (1) may be a cause). But positing (1) as a cause completely misses the point (and is the usual HBDer reductionism to genes causing most/if not all things). It’s the usual HBD/Rushtonian reductionism to genes. That’s all the HBD worldview reduces to: genes/IQ.

In any case, Reschovsky and O’Malley (2008: 229, 230)

Our results indicate that the minority makeup of physicians’ patient panels is associated with greater reports from physicians of difficulties providing high-quality care. At least some of this relationship appears to be explained by the lower resources flowing to high-minority practices.

The results of this study suggest that racial and ethnic disparities in primary health care are in part systemic in nature, and the lower resources flowing to physicians treating more minority patients are a contributing factor.

Thus, bias—whether conscious or unconscious—by physicians can explain how and why there are differences in health outcomes between people that have the same health insurance and doctor. Barr (2014: 168) states that “for black Americans, where a person lives sems to be associated with access to primary care, the quality of available hospital care, and the quality of available home care.” Barr shows that blacks receive a different level of care for a wide-range of diseases and illnesses compared to whites. For instance, Smedley et al (2003) write that “some evidence suggests that bias, prejudice, and stereotyping on the part of healthcare providers may contribute to differences in care.” Quite clearly, there is racial bias against minorities and it does seem to affect healthcare, whether or not it is intended or unintended (conscious or unconscious) (Williams and Rucker, 2000). Bird and Clinton (2001: 255) write:

Race and class-based structuring of the U.S. health delivery system has combined with other factors, including physicians’ attitudes—perhaps legacies conditioned by their participation in slavery and creation of the scientific myth of black biological and intellectual inferiority—to create a medical-social, health system cultural, and health delivery environment which contributes to the propagation of racial health disparities, and, ultimately, the health system’s race and class dilemma.

Blacks are more likely to take the advice of physicians, and to use the needed services, such as preventative care and are less likely to delay seeking care when the physician is of their own race (Saha et al, 2000; LaVeist, Nuru-Jeter, and Jones, 2008).

Blacks are more likely to perceive racism in healthcare and when they are able to choose their own doctors, they are more satisfied with their level of care (Chen et al, 2005). Chapman, Kaatz, and Carnes (2013) show that increasing awareness of implicit bias in healthcare can lower such disparities, stating that having more black doctors will alleviate such problems since they are less likely to be biased. Having a black doctor lead to more effective care for black men. Quite clearly, the race of the doctor matters for implicit biases and minority doctors lead to more effective healthcare for minorities, since they are less likely to be affected by racial biases. Minorities trust the healthcare system less than whites (Boulware et al, 2003). Black and white physicians even agree that race is a medically relevant data point, but do not agree on why (Bonham et al, 2009).

Conclusion

The table presented by Barr is telling. He purported to show that on certain indices of health, certain states fair worse than others. Rates of illness and rates of death between different states (with differing ethnic compositions) were compared. Using national data, he showed that Mississippi has the highest rates of death and illness (sans asthma). Social factors can and do account for the differences in hypertension between blacks and whites (and States); food deserts (lack of access to good food) can explain higher rates of obesity and diabetes and also higher rates of blood pressure between the races (and States with a higher percentage of certain racial/ethnic groups). Of course, physiological variables are affected by the social environment, so we have to look at differences in the social environment between groups to see how and why there are differences in any physiological variable we look at.

Doctors, whether consciously or not, treat minority patients differently and there is evidence that this leads to differences in health outcomes between ethnic groups in America. PP’s hypotheses don’t cut it (the only one that does it his “EGIs”, but that explanation fails; the cause is bias by the doctors but “EGIs” have nothing to do with the bias). In any case, there are social and cultural reasons why there are such health disparities between States and races/ethnies. Understanding the causes behind them can and will lead to closing the gap between them. The social can and does become biological, and this is the perfect way to show this. There are ways to lower the disparities in a medical context, and education seems to be one of them—for both patient and doctor.

Some states are healthier than others based on objective measures of health and mortality, and understanding the reasons why can and will decrease these differences.

Race, Medicine, and Epigenetics: How the Social Becomes Biological

2050 words

Race and medicine is a tendentious topic. On one hand, you have people like sociologist Dorothy Roberts (2012) who argues against the use of race in a medical context, whereas philosopher of race Michael Hardimon thinks that we should not be exclusionists about race when it comes to medicine. If there are biological races, and there are salient genetic differences between them, then why should we disregard this when it comes to a medically relevant context? Surely Roberts would agree that we use her socio-political concept of race when it comes to medicine, but not treat them like biological races. Roberts is an anti-realist about biological races, whereas Hardimon is not—he recognizes that there is a minimalist and social aspect to race which are separate concepts.

In his book Rethinking Race: The Case for Deflationary Realism, Hardimon (2017, Chapter 8) discusses race and medicine after discussing and defending his different race concepts. If race is real—whether socially, biologically, or both—then why should we ignore it when it comes to medical contexts? It seems to me that many people would be hurt by such a denial of reality, and that’s what most people want to prevent, and which is the main reason why they deny that races exist, so it seems counterintuitive to me.

Hardimon (2017: 161-162; emphasis his) writes:

If, as seems to be the case, the study of medically relevant genetic variants among races is a legitamate project, then exclusionism about biological race in medical research—the view that there is no place for a biological concept of race in medical research—is false. There is a place for a biological concept of race in the study of medically relevant genetic variants among races. Inclusionism about biological race in medical research is true.

So, we should not be exclusionists (like Roberts), we should be inclusionists (like Hardimon). Sure, some critics would argue that we should be looking at the individual and not their racial or ethnic group. But consider this: Imagine that an individual has something wrong and standard tests do not find out what it is. The doctor then decides that the patient has X disease. They then treat X disease, and then find out that they have Y disease that a certain ethnic group is more likely to have. In this case, accepting the reality of biological races and its usefulness in medical research would have caught this disease earlier and the patient would have gotten the help they needed much, much sooner.

Black women are more likely to die from breast cancer, for example, and racism seems like it can explain a lot of it. They have less access to screening, treatment, care, they receive delays in diagnoses, along with lower-quality treatment than white women. But “implicit racial bias and institutional racism probably play an important role in the explanation of this difficult treatment” (Hardimon, 2017: 166). Furthermore, black women are more than twice as likely to acquire a type of breast cancer called “triple negative” breast cancer (Stark et al, 2010; Howlader et al, 2014; Kohler et al, 2015; DeSantis et al, 2019). Of course, this could be a relevant race-related genetic difference in disease.

We should, of course, use the concepts of socialrace when discussing the medical effects of racism (i.e., psychosocial stress) and the minimalist/populationist race concepts when discussing the medically relevant race-related genetic diseases. Being eliminativist about race doesn’t make sense—since if we deny that race exists at all and do not use the term at all anymore, there would be higher mortality for these “populations.” Thus, we should use both of Hardimon’s terms in regard to medicine and racial differences in health outcomes as both concepts can and will show us how and why diseases are more likely to appear in certain racial groups; we should not be eliminativists/exclusionists about race, we should be inclusionists.

Hardimon discusses how racism can manifest itself as health differences, and how this can have epigenetic effects. He writes (pg 155-156):

As philosopher Shannon Sullivan explains, another way in which racism may be shown to influence health is by causing epigenetic changes in the genotype. It is known that changes in gene expression can have durable and even transgenerational effects on health, passing from parents to their children and their children’s children. This suggests that the biological dimensions of racism can replicate themselves across more than one generation through epigenetic mechanisms. Epigenetics, the scientific study of such changes, explains how the process of transgenerational biological replication of ill health can occur without changes in the underlying DNA sequence.

If such changes to the DNA sequences can be transmitted to the next generation in the developmental system, then that means that the social can—and does—has an effect on our biology and that it can be passed down through subsequent generations. It is simple to explain why this makes sense: for if the developing organism was not plastic, and genes could not change based on what occurs in the environment for the fetus or the organism itself, then how could organisms survive when the environment changes if the “genetic code” of the genome were fixed and not malleable? For example, Jasienska (2009) argues that:

… the low birth weight of contemporary African Americans not only results from the difference in present exposure to lifestyle factors known to affect fetal development but also from conditions experienced during the period of slavery. Slaves had poor nutritional status during all stages of life because of the inadequate dietary intake accompanied by high energetic costs of physical work and infectious diseases. The concept of ‘‘fetal programming’’ suggests that physiology and metabolism including growth and fat accumulation of the developing fetus, and, thus its birth weight, depend on intergenerational signal of environmental quality passed through generations of matrilinear ancestors.