Home » Race Realism (Page 2)

Category Archives: Race Realism

Strategies for Achieving Racial Health Equity: An Argument for When Health Inequalities are Health Inequities

2100 words

Introduction

Health can be defined as “a relative state in which one is able to function well physically, mentally, socially, and spiritually to express the full range of one’s unique potentialities within the environment in which one lives” (Svalastog et al, 2017). Health, clearly, is a multi-dimensional concept (Barr, 2014). Since there are many kinds of referents to the word “health”, it is therefore essential to understand and consider the context and perspective of each person and group when discussing health-related issues and also while implementing healthcare policies and practices.

Inequality exists everywhere on earth and it manifests in numerous forms like in income, health, education, and healthcare access. So the existence of inequality is undeniable, since we can see it with our own eyes, but understanding the mechanisms that lead to inequality should be multifaceted. Central to the understanding of inequality is the relationship between inequality, unfairness and the role of empirical investigations in uncovering not only the implications for societal outcomes, but also in discerning what is an inequity (which is a kind of inequality that is avoidable, unfair and unjust). According to Braveman, (2003: 182):

Health inequities are disparities in health or its social determinants that favour the social groups that were already more advantaged. Inequity does not refer generically to just any inequalities between any population groups, but very specifically to disparities between groups of people categorized a priori according to some important features of their underlying social position.

Talking about health is the best way to understand what inequity actually is. The issue is, true equality of health is impossible, but what is possible is addressing the actual social determinants of health (SDoH). What is also important is understanding what equity is and what equity isn’t, as I have argued in the past. Grifters like James Lindsay and Chris Rufo (along with well-meaning but still wrong institutions) believe that equity is ensuring equal outcomes. This is incorrect. What equity means—in the health sphere—is when “the opportunity to ‘attain their full health potential’ and no one is ‘disadvantaged from achieving this potential because of their social position or other socially determined circumstance’” (Braveman, quoted by the CDC).Therefore, health equity is when everyone has the chance to reach their fill potential, unabated by social determinants. Social conditions and policies strongly influence the health of both individuals and groups and it’s the result of unequal distribution of resources and opportunities. Empirical investigation is pivotal in understanding if a certain inequality is an inequity. And although inequities are a kind of inequality, “inequality” and “inequity” are conceptually distinct (Braveman, 2003).

In this article I will discuss the SDoH, give my argument that we can identify inequity (a kind of inequality) through empirical investigations (meaning that they are avoidable, unfair and unjust). I will then pivot to a real-world example of my argument—that of low birth weight in black American newborns and argue that racism and historical injustices can explain that since non-American black women have children with higher mean birth weights. I will then discuss how blacks who have doctors of of the same race report better care and have higher life expectancies. I will then discuss what can be done about this—and the answer is to educate people on genetic essentialism which leads to racism and racist attitudes.

On SDoH

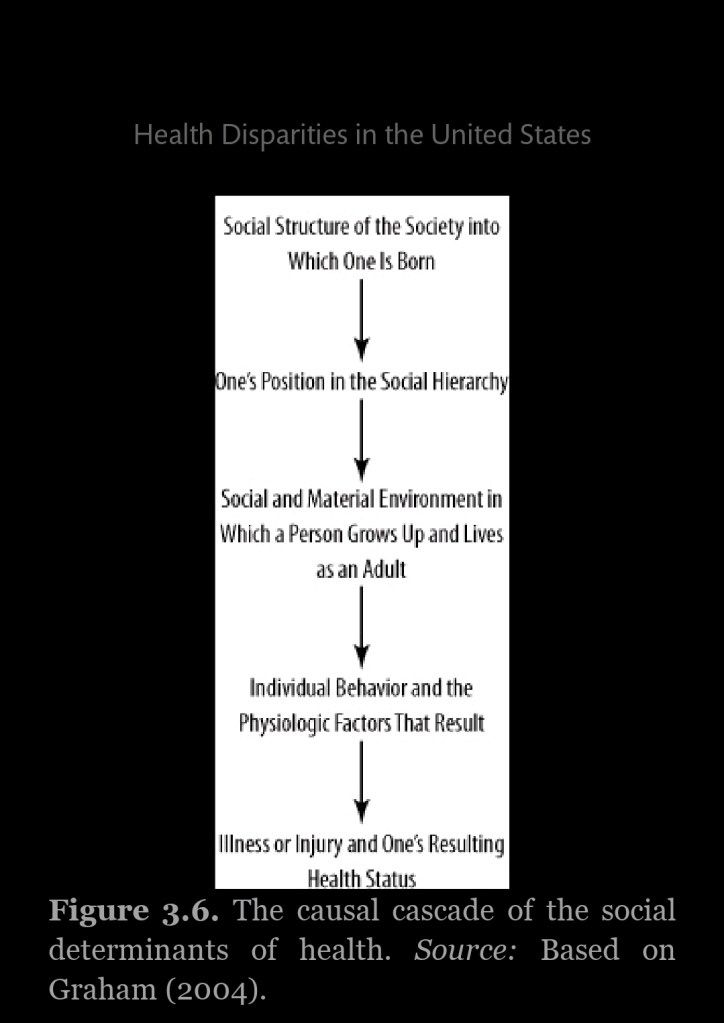

SDoH include the lack of education, racism, lack of access to health care and poverty. Barr (2011: 64) had a helpful flow chart to understand this issue.

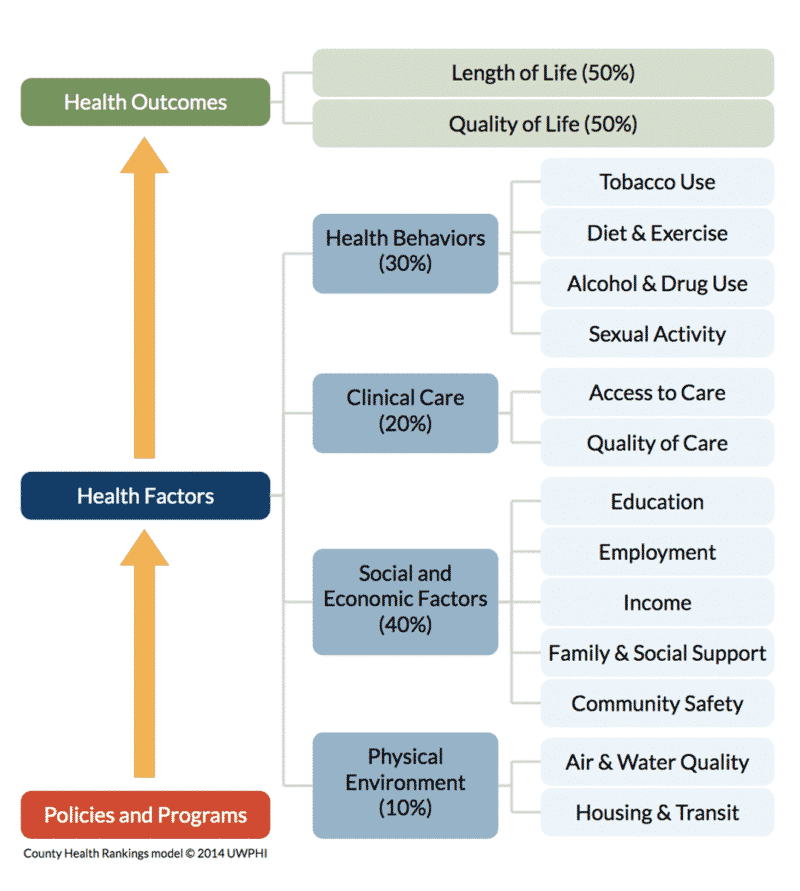

So when it comes to variation in health outcomes, we know that only 20 percent can be attributed to access to medical care, while a whooping 80 percent is attributable to the SDoH:

(Ratcliffe, 2017 also states that about 20 percent of the health of nation is attributed to medical care, 5 percent the result of biology and genes, 20 percent the result of individual action, and 50 percent due to the SDoH.)

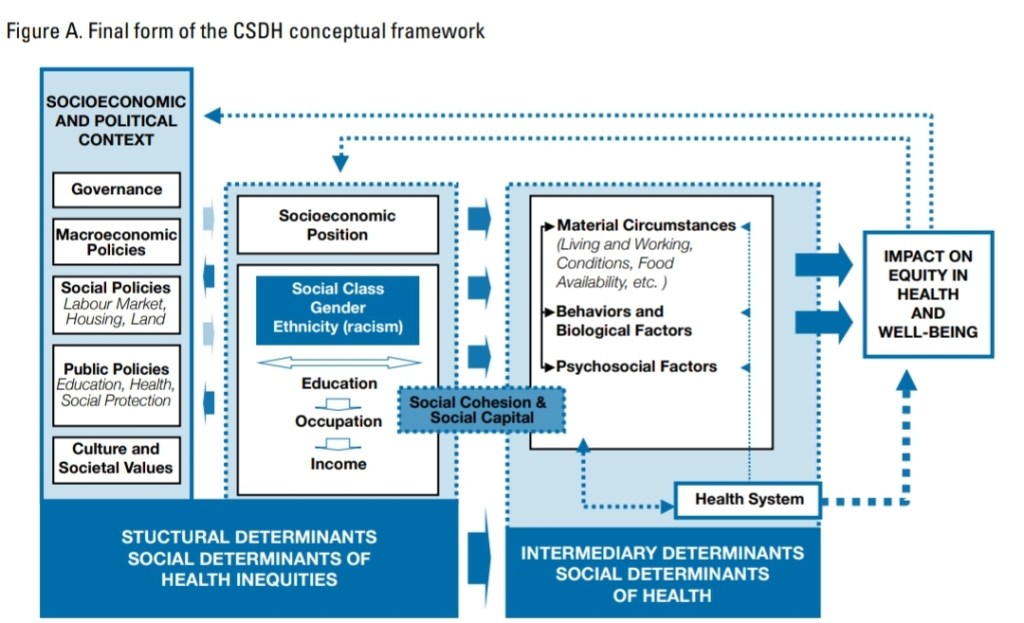

The WHO (2010) also has a Commission on the Social Determinants of Health (CSDH) with a conceptual framework:

This is staggering. For if the social determinants of health are causal for health outcomes, then it comes down to how society is structured along with how we treat certain people and groups. This also could come down to environmental racism—which is the disproportionate exposure of minority groups to environmental hazards. One pertinent example is lead in paint uses in houses in the 80s, where groups actually used blacks as a kind of experiment in seeing the effects of lead. The issue was further exacerbated by Big Lead in trying to argue that the families had a “history of low intelligence” and that it couldn’t be proven that lead had the damaging effects on the children. Not only does environmental racism cause negative health effects, but so does individual racism which is known to have a negative effect on black women. (Racism and stereotypes which lead to self-fulfilling prophecies also cause the black-white crime gap.)

So empirical research—grounded in data and evidence—can help us in understanding whether a given inequality is an inequity. Certain disparities could reflect historical disadvantages which then perpetuate cycles of disadvantage which then reinforce existing power structures and further continue to marginalize certain communities.

The argument

I have constructed an argument that shows what I am talking about:

UO: Unequal outcome

I: Inequality

A: Avoidable

F: Unfair

J: Unjust

E: Empirical investigation

I involves A, F, J. E may reveal instances where I leads to UO and I is associated with F, J, and A.

Premise 1: E -> (A^F^J)

Premise 2: I -> (A^F^J)

Conclusion: E -> ((I -> UO) ^ (A^F^J))

(P1) If empirical investigations (E) reveal instances where avoidable factors (A), unfairness (F) and injustice (J) are present, and (P2) if inequality (I) leads to conditions involving avoidability (A), unfairness (F) and injustice (J), then (Conclusion) empirical investigations (E) could reveal instances where inequality leads to unequal outcomes (UO), and whether or not they are avoidable (A), unfair (F) or unjust (J). Effectively, since inequities are a kind of inequality, then this can identify inequities where they are, and then we can work to fix them.

For instance, birth weight has decreased recently and the effect is more pronounced for black women (Catov et al, 2016) and racism could as well be a culprit (Collins Jr., et al, 2004). There is also evidence that structural racism in the workplace can and has attributed to this (Chantarat et al, 2022). It’s quite clear that racism can explain birth outcome disparities (Dominguez et al, 2010; Alhusen et al, 2016; Dreyer, 2021). Not only does racism contribute to adverse birth outcomes but so too do factors related to environmental racism (Burris and Hacker, 2018). This also has a historical precedent: slavery (Jasienska, 2009). Hereditarians may try to argue that (as always) this difference has a genetic basis. But we know that African women born in Africa are heavier than African American women; black women born in Africa have children with higher mean birth weights than African American women (David and Collins, 1997). Cabral et al (1991) also found the same—non-American black women birthed children that weighed 135 more grams than American black women. Thus, the difference isn’t genetic in nature—it is environmentally caused and it partly stems from slavery. Clearly this discussion shows that my argument has a real-world basis.

How do we reverse these inequities?

Clearly, racism has societal consequences not only for crime and mental illness, but also low birth weight in black American women. The difference can’t be genetic in nature, so it’s obviously environmental/social in nature due to racism, environmental racism. So how can we alleviate this? There are a few ways.

We can improve access to pre-natal care. By ensuring equitable access to pre-natal care, and by expanding Medicaid coverage, we can the begin to address the issue of low black birth weight. We know that when black newborns are cared for by black doctors, they have a better survival rate (Greenwood et al, 2020). We also have an RCT showing that black doctors could reduce the black-white cardiovascular mortality rate by 19 percent (Alsan, Garrick, and Grasiani, 2019). We also know that a higher percentage of black doctors leads to lower mortality rate and better life expectancy (Peek, 2023; Snyder et al, 2023). This isn’t a new finding—we’ve known this since the 90s (Komaramy et al, 1996; Saha et al, 1999). We also know that people who have same-race doctors are more likely to accept much-needed preventative care (LaVeist, Nuru-Jeter, and Jones, 2003). This could then lead to less systemic bias in healthcare, since we know that some of the difference is systemic in nature (Reschovsky and O’Malley 2008: 229, 230). We also know that bias, stereotyping, and prejudice also play a part (Smedley et al, 2003). Such stereotypes are also sometimes unconscious (Williams and Rucker, 2000). The medical system contributes to said disparities (Bird and Clinton, 2001). Blacks who perceived more racism in healthcare felt more comfortable with a black doctor (Chen et al, 2005)—minorities also trust the healthcare system less than whites (Boulware et al, 2003). Lastly, black and white doctors agree that race is a medically relevant data point, but they don’t agree on why (Bonham et al, 2009).

We know that systemic and structural racism exists and that it impacts health outcomes (Braveman et al, 2022). Some may say that systemic and structural racism don’t exist, but this claim is clearly false. They are “are forms of racism that are pervasively and deeply embedded in and throughout systems, laws, written or unwritten policies, entrenched practices, and established beliefs and attitudes that produce, condone, and perpetuate widespread unfair treatment of people of color. They reflect both ongoing and historical injustices” (Braveman et al, 2022). Perhaps the most important way that systemic racism can harm health is through placing people at an economic disadvantage and stress. Environmental racism then compounds this, and then unfair treatment then leads to higher levels of stress which then leads to negative health outcomes.

Lastly a key issue here is the prevalence of racism. We know that it has a slew of negative health effects and that it affects the incidence of the black-white crime gap. But what can be done to alleviate racist attitudes?

Since many racist ideas have a genetically essentialist tilt, then we can use education to ameliorate racist attitudes (Donovan, 2022). We also know that racial essentialist attitudes are related to the belief that evolution has an intentional tilt and that it’s negatively correlated with biology grades (Donovan, 2015). Much of Donovan’s work shows that education can ameliorate racist attitudes which are due to genetic essentialism. We also know that such essentialist thinking is related to misconceptions about heredity and evolution and is correlated with low grades at the end of the semester in beginner biology course (Donovan, 2016). Thus, by providing accurate and understandable education on race, genetics, and evolution, people may be less likely to hold racial essentialist attitudes and more likely to reject racist ideologies. So there are actionable things we can do to combat racism which leads to crime and negative health outcomes for minority groups.

Conclusion

The SDoH play a pivotal role in shaping the health outcomes while perpetuating health inequities. We can, through empirical investigations, ascertain when an inequality is avoidable, unfair and unjust (meaning, when it is an inequity). We can then understand how historical injustices like racism impact marginalized communities which then contribute to negative health outcomes like low birth weight of black American babies. We know that it’s not a genetic difference since non-American black women have children with higher mean birth weights than black American women, and this suggests thar historical injustices and racism are a cause (as Jasienska argues). Further, studies show that when black patients have black doctors, they report better care and have higher life expectancies. Research has also shown that education can play a role in ameliorating genetic essentialist and racist attitudes which then, as I’ve shown, lead to negative health outcomes. The argument I’ve made here has a real-world basis in the case of low birth weight of black American babies.

In sum, committing to social and racial justice can help to change these inequities, and for that, we will have a better and more inclusive society where people’s negative health outcomes aren’t caused by social goings-on. To achieve racial health equity, we must address the avoidable, unfair and unjust factors that contribute to these inequities.

The “Great Replacement Theory”

2550 words

Introduction

The “Great Replacement Theory” (GRT hereafter) is a white nationalist conspiracy theory (conceptualized by French philosopher Renaud Camus) where there is an intentional effort by some shadowy group (i.e., Jews and global elites) to bring mass amounts of immigrants with high TFRs to countries with whites where whites have low TFRs in order to displace and replace whites in those countries (Beirich, 2021). Vague statements have been made about their “IQs” in that they would be easier to “control” and that they would then intermix with whites to further decrease the IQ of the nation and then be more controllable, all the while the main goal of the GRT—the destruction of the white race—would come to fruition. Here, I will go through the logic of what I think the two premises of the GRT are, and then I will show how the two premises (which I hold to obviously be true) don’t guarantee the conclusion that the GRT is true and that there is an intentional demographic replacement. I will discuss precursors of this that are or almost are 100 years old. I will then discuss what “theory” and “conspiracy theory” means and how, by definition, the GRT is both a theory (an attempted explanation of observed facts) and a conspiracy theory (suggesting a secret plan for the destruction and replacement of the white race).

The genesis of the GRT

The idea of the GRT is older than what spurred it’s discussion in the new millennium, but it can be traced in its modern usage to French political commentator Renaud Camus in his book Le Grand Remplacement.

But one of the earliest iterations of the GRT is the so-called “Kalergi plan.” Kalergi was also one of the founders of the pan-European union (Wiedemer, 1993). Kalergi, in his 1925 book Practical Idealism, wrote that “The man of the future will be of mixed race. Today’s races and classes will gradually disappear owing to the vanishing of space, time, and prejudice. The Eurasian-Negroid race of the future will replace the diversity of peoples with a diversity of individuals.” Which is similar to what Grant (1922: 110) wrote in The Passing of the Great Race:

All historians are familiar with the phenomenon of a rise and decline in civilization such as has oc- curred time and again in the history of the world but we have here in the disappearance of the Cro-Magnon race the earliest example of the replacement of a very superior race by an inferior one. There is great danger of a similar replacement of a higher by a lower type here in America unless the native American uses his superior intelligence to protect himself and his children from competition with intrusive peoples drained from the lowest races of eastern Europe and western Asia.

The idea of a great replacement is obviously much older than what spurred it on today. Movement was much tougher back then as the technology for mass migrations was just beginning to become more mainstream (think of the mass migrations from the 1860s up until the 1930s in America from European groups). Even the migration of other whites from Europe was used as a kind of “replacement” of protestant Anglo-Saxon ways of life. Nonetheless, these ideas of a great replacement are not new, and these two men (one of which—Kalergi—wasn’t using the quote in a nefarious way, contra the white nationalists who use this quote as evidence of the GRT and the plan for it in the modern day) are used as evidence that it is occurring.

Kalergi envisioned a positive blending of the races, whereas Grant expressed concerns of replacement by so-called “inferior” groups replacing so-called “superior” groups. Grant—in trying to argue that Cro-Magnon man was the superior race, replaced by the inferior one—expressed worry of intentional demographic replacement, which is the basis of the GRT today and what the GRT essentially reduces to. The combination of these opposing perspectives of the mixing of races (the positive one from Kalergi and the negative one from Grant) show that the idea of a great replacement is much older than Camus’ worry in his book. (And, as I will argue, the fact that the 2 below premises are true doesn’t guarantee the conclusion of the GRT.)

The concept of the GRT

The GRT has two premises:

(1) Whites have fewer children below TFR

(2) Immigrants have more children above TFR

Which then should get us to:

(C) Therefore, the GRT is true.

But how does (C) follow from (1) and (2)? The GRT suggests not only a demographic shift in which the majority (whites) are replaced and displaced by minorities (in this case mostly “Hispanics” in America), but that this is intentional—that is, it is one man or group’s intention for this to occur. The two premises above refer to factual, verifiable instances: Whites have fewer children; immigrants coming into America have more children. BUT just because those two premises are true, this does NOT mean that the conclusion—GRT is true—follows from the two premises. The two premises focus on the fertility rates of two groups (American whites and immigrants to America), but acceptance of both of those premises does not mean that there is an act of intentional displacement occurring. We can allow the truth of both premises, but that doesn’t lead to the truth of the GRT. Because that change is intentionally driven by some super secret, shadowy and sinister group (the Jews or some other kind of amalgamation of elites who want easy “slave labor”).

The GRT was even endorsed by the Buffalo shooter who heniously shot and killed people in a Tops supermarket. He was driven by claims of the GRT. (The US Congress condemned the GRT as a “White supremacist conspiracy theory“, and I will show how it is a theory and even a conspiracy theory below.) The shooter even plagiarized the “rationale section” of his manifesto (Peterka-Benton and Benton, 2023). This shows that such conspiracy theories like the GRT can indeed lead to radicalization of people.

Even ex-presidential hopeful Vivek Ramaswamy made reference to the GRT, stating that “great replacement theory is not some grand right-wing conspiracy theory, but a basic statement of the Democratic Party’s platform.” Even former Fox News political commentator Tucker Carlson has espoused these beliefs on his former show on Fox News. The belief in such conspiratorial thinking can quite obviously—as seen with the Buffalo shooter—have devestating negative consequences (Adam-Troian et al, 2023). Thus, these views have hit the mainstream as something that’s “plausible” on the minds of many Americans.

Such thinking obviously can be used for both Europe and America—where the Islamization/Africanization of Europe and the browning of America with “Hispanics” and other groups—where there is a nefarious plot to replace the white population of both locations, and these mostly derive on places like 4chan where they try to “meme” what they want into reality (Aguilar, 2023).

On theories and conspiracy theories

Some may say that the GRT isn’t a theory nor is it even a conspiracy theory—it’s a mere observation. I’ve already allowed that both premises of the argument—whites have fewer children below TFR while immigrants have more children above TFR—is true. But that doesn’t mean that the conclusion follows that the GRT is true. Because, as argued above, it is intentional demographic replacement. Intentional by whom? Well the Jews and other global elites who want a “dumb” slave population that just listens, produces and has more children so as to continue the so-called enslavement of the lower populations.

But, by definition, the GRT is a theory and even a conspiracy theory. The GRT is a theory in virtue of it being an explanation for observed demographic changes and the 2 premises I stated above. It is a conspiracy theory because it suggests a deliberate, intentional plan by the so-called global elite to replace whites with immigrants. Of course labeling something as a conspiracy theory doesn’t imply that it’s inaccurate nor invalid, but I would say that the acceptance of both premises DO NOT guarantee the conclusion that those who push the GRT want it to.

The acceptance of both premises doesn’t mean that the GRT is true. The differential fertility of two groups, where one group (the high fertility group) is migrating into the country of another group (the low fertility group) doesn’t mean that there is some nefarious plot by some group to spur race mixing and the destruction and replacement of one group over another.

As shown above, people may interpret and respond to the GRT in different ways. Some may use it in a way to interpret and understand demographic changes while not committing henious actions, while others—like the Buffalo shooter—may use the information in a negative way and take many innocent lives on the basis of belief in the theory. Extreme interpretations of the GRT can lead to the shaping of beliefs which then contribute to negative actions based on the belief that their group is being replaced (Obaidi et al, 2021). Conspiracy theories also rely on the intent to certain events, of which the proponents of the GRT do.

Some white nationalists who hold to the GRT state that the Jews are behind this for a few reasons—one of which I stated above (that they want dumber people to come in who have higher TFRs to replace the native white population in the country)—and another reason which has even less support (if that’s even possible) which is that the Jews are orchestrating the great migration of non-whites into European countries as revenge and retaliation for Europeans expelling Jews from European countries during the middle ages (109 countries). This is the so-called “white genocide” conspiracy theory. This is the kind of hate that Trump ran with in his presidential run and in his time in office as president of the United States (Wilson, 2018). This can also be seen with the phrase “Jews/You will not replace us!” during the Charlottesville protests of 2017 (Wilson, 2021). “You” in the phrase “You will not replace us!” could refer to Jews, or it could refer to the people that the Jews are having migrate into white countries to replace the white population. Beliefs in such baseless conspiracy theories gave led to mass murder in America, Australia, and Norway (Davis, 2024).

One of the main actors in shaping the view that Jews are planning to replace (that is, genocide) Whites is white nationalist and evolutionary psychologist Kevin MacDonald, more specifically in his book series on the origin of Jewish evolutionary group strategies, with A People that Shall Dwell Alone (1994), Separation and it’s Discontents (1998a), and The Culture of Critique (1998b). It is a main argument in this book series that the Jews have an evolved evolutionary group strategy that has them try to undermine and destroy white societies (see Blutinger, 2021 and also Nathan Cofnas’ responses to MacDonald ‘s theory). MacDonald’s theory of a group evolutionary strategy is nothing more than a just-so story. Such baseless views have been the “rationale” of many mass killings in the 2010s (eg Fekete, 2011; Nilsson, 2022). Basically it’s “white genocide is happening and the Jews are behind it so we need to kill those who the Jews are using to enact their plan and we need to kill Jews.” (Note that this isn’t a call for any kind of violence it’s just a simplified version of what many of these mass killers imply in their writings and motivations for carrying out their henious attacks.) One thing driving these beliefs and that jd the GRT is that of anti-Semitism (Allington, Buarque, and Flores, 2020). Overall, such claims of a GRT or “white genocide” flourish online (Keulennar and Reuters, 2023). In this instance, it is claimed that Jews are using their ethnic genetic interests and nepotism to spur these events.

Conclusion

I have discussed the GRT argument and with it so-called “white genocide” (since the two are linked). The 2 premises of the GRT are tru—that American whites have low TFR and those who are emigrating have high TFR—but but that the premises are true doesn’t guarantee the conclusion that there is some great replacement occurring, since it reduces to a kind of intentional demographic replacement by some group (say, the Jews and other elites in society who want cheap, dumb, easily controllable labor who have more children). The GRT is happening, it is claimed, since the Jews want revenge on whites for kicking them out of so many countries. That is, the GRT is an intentional demographic replacement. Those who push the GRT take the two true premises and then incorrectly conclude that there is some kind of plan to eradicate whites through both the mixing of races and bringing in groups of people who have more children than whites do.

I have scrutinized what I take to be the main argument of GRT proponents and have shown that the conclusion they want doesn’t logically follow. Inherent in this is a hasty generalization fallacy and fallacy of composition (in the argument as I have formalized it). This shows the disconnect between both premises and the desired conclusion. Further, the classification of the GRT as a conspiracy theory comes from the attribution of intention to eliminate and eradicate white through the mass migration of non-white immigrant groups who have more children than whites along with racial mixing.

The Buffalo shooting in a Tops supermarket in 2022 shows the impact of these beliefs on people who want there to be some kind of plan or theory for the GRT. Even mainstream pundits and a political candidate have pushed the GRT to a wider audience. And as can be seen, belief in such a false theory can, does, and has led to the harm and murder of innocent people.

Lastly, I showed how the GRT is a theory (since it is an attempt at an explanation for an observed trend) and a conspiracy theory (since the GRT holds that there is a secret plan, with people behind the scenes in the shadows orchestrating the events of the GRT). Such a shift in demographics need not be the result of some conspiracy theory with the intention to wipe out one race of people. Of course some may use the GRT to try to understand how and why the demographics are changing in the West, but it is mostly used as a way to pin blame on why whites aren’t having more children and why mass immigration is occurring.

All in all, my goal here was to show that the GRT has true premises but the conclusion doesn’t follow, and that it is indeed a theory and a conspiracy theory. I have also shown how such beliefs can and have led to despicable actions. Clearly the impact of beliefs on society can have negative effects. But by rationally thinking about and analyzing such claims, we can show that not only are they baseless, but that it’s not merely an observation of observed trends. Evidence and logic should be valued here, while we reject unwanted, centuries-old stereotypes of the purported plan of racial domination of certain groups.

Race, Racism, Stereotypes, and Crime: An Argument for Why Racism is Morally Wrong

2300 words

Introduction

(1) Crime is bad. (2) Racism causes crime. (C) Thus, racism is morally wrong. (1) is self-evident based on people not wanting to be harmed. (2) is known upon empirical examination, like the TAAO and it’s successful novel predictions. (C) then logically follows. In this article, I will give the argument in formal notation and show its validity while defending the premises and then show how the conclusion follows from the premises. I will then discuss two possible counter arguments and then show how they would fail. I will show that you can derive normative conclusions from ethical and factual statements (which then bypasses the naturalistic fallacy), and then I will give the general argument I am giving here. I will discuss other reasons why racism is bad (since it leads to negative physiological and mental health outcomes), and then conclude that the argument is valid and sound and I will discuss how stereotypes and self-fulfilling prophecies also contribute to black crime.

Defending the argument

This argument is obviously valid and I will show how.

B stands for “crime is bad”, C stands for “racism causes crime”, D stands for racism is objectively incorrect, so from B and C we derive D (if C causes B and B is bad, then D is morally wrong). So the argument is “(B ^ C) -> D”. B and C lead to D, proving validity.

Saying “crime is bad” is an ethical judgement. The term “bad” is used as a moral or ethical judgment. “Bad” implies a negative ethical assessment which suggests that engaging in criminal actions is morally undesirable or ethically wrong. The premise asserts a moral viewpoint, claiming that actions that cause harm—including crime—are inherently bad. It implies a normative stance which implies that criminal behavior is wrong or morally undesirable. So it aligns with the idea that causing harm, violating laws or infringing upon others is morally undesirable.

When it comes to the premise “racism causes crime”, this needs to be centered on the theory of African American offending (TAAO). It’s been established that blacks experiencing racism is causal for crime. So the premise implies that racism is a factor in or contributes to criminal behavior amongst blacks who experience racism. Discriminatory practices based on race (racism) could lead to social inequalities, marginalization and frustration which would then contribute to criminal behavior among the affected person. This could also highlight systemic issues where racist policies or structures create an environment conducive to crime. And on the individual level, experiences of racism could influence certain individuals to engage in criminal activity as a response or coping mechanism (Unnever, 2014; Unnever, Cullen, and Barnes, 2016). Perceived racial discrimination “indirectly predicted arrest, and directly predicted both illegal behavior and jail” (Gibbons et al, 2021). Racists propose that what causes the gap is a slew of psychological traits, genetic factors, and physiological variables, but even in the 1960s, criminologists and geneticists rejected the genetic hypothesis of crime (Wolfgang,1964). However we do know there is a protective effect when parents prepare their children for bias (Burt, Simons, and Gibbons, 2013). Even the role of institutions exacerbates the issue (Hetey and Eberhardt, 2014). And in my article on the Unnever-Gabbidon theory of African American offending, I wrote about one of the predictions that follows from the theory which was borne out when it was tested.

So it’s quite obvious that the premise “racism causes crime” has empirical support.

So if B and C are true then D follows. The logical connection between B and C leads to the conclusion that “racism is morally wrong”, expressed by (B ^ C) -> D. Now I can express this argument using modus ponens.

(1) If (B ^ C) then D. (Expressed as (B ^ C) -> D).

(2) (B ^ C) is true.

(3) Thus, D is true.

When it comes to the argument as a whole it can be generalized to harm is bad and racism causes harm so racism is bad.

Furthermore, I can generalize the argument further and state that not only that crime is bad, but that racism leads to psychological harm and harm is bad, so racism is morally wrong. We know that racism can lead to “weathering” (Geronimus et al, 2006, 2011; Simons, 2021) and increased allostatic load (Barr 2014: 71-72). So racism leads to a slew of unwanted physiological issues (of which microaggressions are a species of; Williams, 2021).

Racism leads to negative physiological and mental health outcomes (P), and negative physiological and mental health outcomes are undesirable (Q), so racism is morally objectionable (R). So the factual statement (P) establishes a link between negative health outcomes, providing evidence that racism leads to these negative health outcomes. The ethical statement (Q) asserts that negative health outcomes are morally undesirable which aligns with a common ethical principle that causing harm is morally objectionable. Then the logical connection (Q ^ P) combines the factual observation of harm caused by racism with the ethical judgment that harm is morally undesirable. Then the normative conclusion (R) follows, which asserts that racial is morally objectionable since it leads to negative health outcomes. So this argument is (Q ^ P) -> R.

Racism can lead to stereotyping of certain groups as more prone to criminal behavior, and this stereotype can be internalized and perpetuated which would then contribute to biased law enforcement and along with it unjust profiling. It can also lead to systemic inequalities like in education, employment and housing which are then linked to higher crime rates (in this instance, racism and stereotyping causes the black-white crime gap, as predicted by Unnever and Gabbidon, 2011 and then verified by numerous authors). Further, as I’ve shown, racism can negatively affect mental health leading to stress, anxiety and trauma and people facing these challenges would be more vulnerable to engage in criminal acts.

Stereotypes and self-fulfilling prophecies

In his book Concepts and Theories of Human Development, Lerner (2018: 298) discusses how stereotyping and self-fulfilling prophecies would arise from said stereotyping. He says that people, based on their skin color, are placed into an unfavorable category. Then negative behaviors were attributed to the group. Then these behaviors were associated with different experience in comparison to other skin color groups. These different behaviors then delimit the range of possible behaviors that could develop. So the group was forced into a limited number of possible behaviors, the same behaviors they were stereotyped to have. So the group finally develops the behavior due to being “channeled” (to use Lerner’s word) which is then “the end result of the physically cued social stereotype was a self-fulfilling prophecy” (Lerner, 2018: 298).

From the analysis of the example I provided and, as well, from empirical literature in support of it (e.g., Spencer, 2006; Spencer et al., 2015), a strong argument can be made that the people of color in the United States have perhaps experienced the most unfortunate effects of this most indirect type of hereditary contribution to behavior–social stereotypes. Thus, it may be that African Americans for many years have been involved in an educational and intellectual self-fulfilling prophecy in the United States. (Lerner, 2018: 299)

This is an argument about how social stereotypes can spur behavioral development, and it has empirical support. Lerner’s claim that perception influences behavior is backed by Spencer, Swanson and Harpalani’s (2015) article on the development of the self and Spencer, Dupree, and Hartman’s (1997) phenomenological variant of ecological systems theory (PVEST). (Also see Cunningham et al, 2023). Spencer, Swanson and Harpalani (2015: 764) write:

Whether it is with images of the super-athlete, criminal, gangster, or hypersexed male, it seems that most of society’s views of African Americans are defined by these stereotypes. The Black male has, in one way or another, captured the imagination of the media to such a wide extent that media representations create his image far more than reality does. Most of the images of the Black male denote physical prowess or aggression and downplay other characteristics. For example, stereotypes of Black athletic prowess can be used to promote the notion that Blacks are unintelligent (Harpalani, 2005). These societal stereotypes, in conjunction with numerous social, political, and economic forces, interact to place African American males at extreme risk for adverse outcomes and behaviors.

A -> B—So stereotypes can lead to self-fulfilling prophecies (if there are stereotypes, then they can result in self-fulfilling prophecies). B -> C—Self-fulfilling prophecies can increase the chance of crime for blacks (if there are self-fulfilling prophecies, then they can increase the chance of crime for blacks. So A -> C—Stereotypes can increase the chance of crime for blacks (if there are stereotypes, then they can increase the chance of crime for blacks). Going back to the empirical studies on the TAAO, we know that racism and stereotypes cause the black-white crime gap (Unnever, 2014; Unnever, Cullen, and Barnes, 2016; Herda, 2016, 2018; Scott and Seal, 2019), and so the argument by Spencer et al and Lerner is yet more evidence that racism and stereotypes lead to self-fulfilling prophecies which then cause black crime. Behavior can quite clearly be shaped by stereotypes and self-fulfilling prophecies.

Responses to possible counters

I think there are 3 ways that one could try to refute the argument—(1) Argue that B is false, (2) argue that C is false, or (3) argue that the argument commits the is-ought fallacy.

(1) Counter premise: B’: “Not all crimes are morally bad, some may be morally justifiable or necessary in certain contexts. So if not all crimes are morally bad, then the conclusion that racism is morally wrong based on the premises (B ^ C) isn’t universally valid.”

Premise B reflects a broad ethical judgment which is based on social norms that generally view actions that cause harm morally undesirable. My argument is based on consequences—that racism causes crime. The legal systems of numerous societies categorize certain actions as crimes since they are deemed morally reprehensible and harmful to individuals and communities. Thus, there is a broad moral stance against actions that cause harm which is reflected in the societal normative stance against actions which cause harm.

(2) Counter premise: C’: “Racism does not necessarily cause crime. Since racism does not necessarily cause crime, then the conclusion that racism is objectively wrong isn’t valid.”

Premise C states that racism causes crime. When I say that, it doesn’t mean that every instance of racism leads to an instance of crime. Numerous social factors contribute to criminal actions, but there is a relationship between racial discrimination (racism) and crime:

Experiencing racial discrimination increases the likelihood of black Americans engaging in criminal actions. How does this follow from the theory? TAAO posits that racial discrimination can lead to feelings of frustration and marginalization, and to cope with these stressors, some individuals may resort to commuting criminal acts as a way to exert power or control in response to their experiences of racial discrimination. (Unnever, 2014; Unnever, Cullen, and Barnes, 2016; Herda, 2016, 2018; Scott and Seal, 2019)

(3) “The argument commits the naturalistic fallacy by inferring an “ought” from an “is.” It appears to derive a normative conclusion from factual and ethical statements. So the transition from descriptive premises to moral judgments lacks a clear ethical justification which violates the naturalistic fallacy.” So this possible counter contends that normative statement B and the ethical statement C isn’t enough to justify the normative conclusion D. Therefore it questions whether the argument has good justification for an ethical transition to the conclusion D.”

I can simply show this. Observe X causing Y (C). Y is morally undesirable (B). Y is morally undesirable and X causes Y (B ^ C). So X is morally objectionable (D). So C begins with an empirical finding. B then is the ethical premise. The logical connection is then established with B ^ C (which can be reduced to “Harm is morally objectionable and racism causes harm”). This then allows me to infer the normative conclusion—D—allowing me to bypass the charge of committing the naturalistic fallacy. Thus, the ethical principle that harm is morally undesirable and that racism causes harm allows me to derive the conclusion that racism is objectively wrong. So factual statements can be combined with ethical statements to derive ethical conclusions, bypassing the naturalistic fallacy.

Conclusion

This discussion centered on my argument (B ^ C) -> D. The argument was:

(P1) Crime is bad (whatever causes harm is bad). (B)

(P2) Racism causes crime. (C)

(C) Racism is morally wrong. (D)

I defended the truth of both premises, and then I answered two possible objections, both rejecting B and C. I then defended my argument against the charge of it committing the naturalistic fallacy by stating that ethical statements can be combined with factual statements to derive normative conclusions. Addressing possible counters (C’ and B’), I argued that there is evidence that racism leads to crime (and other negative health outcomes, generalized as “harm”) in black Americans, and that harm is generally seen as bad, so it then follows that C’ and B’ fail. Spencer’s and Lerner’s arguments, furthermore, show how stereotypes can spur behavioral development, meaning that social stereotypes increase the chance of adverse behavior—meaning crime. It is quite obvious that the TAAO has strong empirical support, and so since crime is bad and racism causes crime then racism is morally wrong. So to decrease the rate of black crime we—as a society—need to change our negative attitudes toward certain groups of people.

Thus, my argument builds a logical connection between harm being bad, racism causing harm and moral undesirability. In addressing potential objections and clarifying the ethical framework I ren, So the general argument is: Harm is bad, racism causes harm, so racism is morally wrong.

Jensen’s Default Hypothesis is False: A Theory of Knowledge Acquisition

2000 words

Introduction

Jensen’s default hypothesis proposes that individual and group differences in IQ are primarily explained genetic factors. But Fagan and Holland (2002) question this hypothesis. For if differences in experience lead to differences in knowledge, and differences in knowledge lead to differences in IQ scores, then Jensen’s assumption that blacks and whites have the same opportunity to learn the content is questionable, and I’d think it false. It is obvious that there are differences in opportunity to acquire knowledge which would then lead to differences in IQ scores. I will argue that Jensen’s default hypothesis is false due to this very fact.

In fact, there is no good reason to accept Jensen’s default hypothesis and the assumptions that come with it. Of course different cultural groups are exposed to different kinds of knowledge, so this—and not genes—would explain why different groups score differently on IQ tests (tests of knowledge, even so-called culture-fair tests are biased; Richardson, 2002). I will argue that we need to reject Jensen’s default hypothesis on these grounds, because it is clear that groups aren’t exposed to the same kinds of knowledge, and so, Jensen’s assumption is false.

Jensen’s default hypothesis is false due to the nature of knowledge acquisition

Jensen (1998: 444) (cf Rushton and Jensen, 2005: 335) claimed that what he called the “default hypothesis” should be the null that needs to be disproved. He also claimed that individual and group differences are “composed of the same stuff“, in that they are “controlled by differences in allele frequencies” and that these differences in allele frequencies also exist for all “heritable” characters, and that we would find such differences within populations too. So if the default hypothesis is true, then it would suggest that differences in IQ between blacks and whites are primarily attributed to the same genetic and environmental influences that account for individual differences within each group. So this implies that genetic and environmental variances that contribute to IQ are therefore the same for blacks and whites, which supposedly supports the idea that group differences are a reflection of individual differences within each group.

But if the default hypothesis were false, then it would challenge the assumption that genetic and environmental influences in IQ between blacks and whites are proportionally the same as seen in each group. Thus, this allows us to talk about other causes of variance in IQ between blacks and whites—factors other than what is accounted for by the default hypothesis—like socioeconomic, cultural, and historical influences that play a more substantial role in explaining IQ differences between blacks and whites.

Fagan and Holland (2002) explain their study:

In the present study, we ensured that Blacks and Whites were given equal opportunity to learn the meanings of relatively novel words and we conducted tests to determine how much knowledge had been acquired. If, as Jensen suggests, the differences in IQ between Blacks and Whites are due to differences in intellectual ability per se, then knowledge for word meanings learned under exactly the same conditions should differ between Blacks and Whites. In contrast to Jensen, we assume that an IQ score depends on information provided to the learner as well as on intellectual ability. Thus, if differences in IQ between Blacks and Whites are due to unequal opportunity for exposure to information, rather than to differences in intellectual ability, no differences in knowledge should obtain between Blacks and Whites given equal opportunity to learn new information. Moreover, if equal training produces equal knowledge across racial groups, than the search for racial differences in IQ should not be aimed at the genetic bases of IQ but at differences in the information to which people from different racial groups have been exposed.

There are reasons to think that Jensen’s default hypothesis is false. For instance, since IQ tests are culture-bound—that is, culturally biased—then they are biased against a group so they therefore are biased for a group. Thus, this introduces a confounding factor which challenges the assumption of equal genetic and environmental influences between blacks and whites. And since we know that cultural differences in the acquisition of information and knowledge vary by race, then what explains the black-white IQ gap is exposure to information (Fagan and Holland, 2002, 2007).

The Default Hypothesis of Jensen (1998) assumes that differences in IQ between races are the result of the same environmental and genetic factors, in the same ratio, that underlie individual differences in intelligence test performance among the members of each racial group. If Jensen is correct, higher and lower IQ individuals within each racial group in the present series of experiments should differ in the same manner as had the African-Americans and the Whites. That is, in our initial experiment, individuals within a racial group who differed in word knowledge should not differ in recognition memory. In the second, third, and fourth experiments individuals within a racial group who differed in knowledge based on specific information should not differ in knowledge based on general information. The present results are not consistent with the default hypothesis.(Fagan and Holland, 2007: 326)

Historical and systematic inequalities could also lead to differences in knowledge acquisition. The existence of cultural biases in educational systems and materials can create disparities in knowledge acquisition. Thus, if IQ tests—which reflect this bias—are culture-bound, it also questions the assumption that the same genetic and environmental factors account for IQ differences between blacks and whites. The default hypothesis assumes that genetic and environmental influences are essentially the same for all groups. But SES/class differences significantly affect knowledge acquisition, so if challenges the default hypothesis.

For years I have been saying, what if all humans have the same potential but it just crystallizes differently due to differences in knowledge acquisition/exposure and motivation? There is a new study that shows that although some children appeared to learn faster than others, they merely had a head start in learning. So it seems that students have the same ability to learn and that so-called “high achievers” had a head start in learning (Koedinger et al, 2023). They found that students vary significantly in their initial knowledge. So although the students had different starting points (which showed the illusion of “natural” talents), they had more of a knowledge base but all of the students had a similar rate of learning. They also state that “Recent research providing human tutoring to increase student motivation to engage in difficult deliberate practice opportunities suggests promise in reducing achievement gaps by reducing opportunity gaps (63, 64).”

So we know that different experiences lead to differences in knowledge (it’s type and content), and we also know that racial groups for example have different experiences, of course, in virtue of their being different social groups. So these different experiences lead to differences in knowledge which are then reflected in the group IQ score. This, then, leads to one raising questions about the truth of Jensen’s default hypothesis described above. Thus, if individuals from different racial groups have unequal opportunities to be exposed to information, then Jensen’s default hypothesis is questionable (and I’d say it’s false).

Intelligence/knowledge crystalization is a dynamic process shaped by extensive practice and consistent learning opportunities. So the journey towards expertise involves iterative refinement with each practice opportunity contribute to the crystallization of knowledge. So if intelligence/knowledge crystallizes through extensive practice, and if students don’t show substantial differences in their rates of learning, then it follows that the crystalization of intelligence/knowledge is more reliant on the frequency and quality of learning opportunities than on inherent differences in individual learning rates. It’s clear that my position enjoys some substantial support. “It’s completely possible that we all have the same potential but it crystallizes differently based on motivation and experience.” The Fagan and Holland papers show exactly that in the context of the black-white IQ gap, showing that Jensen’s default hypothesis is false.

I recently proposed a non-IQ-ist definition of intelligence where I said:

So a comprehensive definition of intelligence in my view—informed by Richardson and Vygotsky—is that of a socially embedded cognitive capacity—characterized by intentionality—that encompasses diverse abilities and is continually shaped by an individual’s cultural and social interactions.

So I think that IQ is the same way. It is obvious that IQ tests are culture-bound and tests of a certain kind of knowledge (middle-class knowledge). So we need to understand how social and cultural factors shape opportunities for exposure to information. And per my definition, the idea that intelligence is socially embedded aligns with the notion that varying sociocultural contexts do influence the development of knowledge and cognitive abilities. We also know that summer vacation increases educational inequality, and that IQ decreases during the summer months. This is due to the nature of IQ and achievement tests—they’re different versions of the same test. So higher class children will return to school with an advantage over lower class children. This is yet more evidence in how knowledge exposure and acquisition can affect test scores and motivation, and how such differences crystallize, even though we all have the same potential (for learning ability).

Conclusion

So intelligence is a dynamic cognitive capacity characterized by intentionality, cultural context and social interactions. It isn’t a fixed trait as IQ-ists would like you to believe but it evolves over time due to the types of knowledge one is exposed to. Knowledge acquisition occurs through repeated exposure to information and intentional learning. This, then, challenges Jensen’s default hypothesis which attributes the black-white IQ gap primarily to genetics.Since diverse experiences lead to varied knowledge, and there is a certain type of knowledge in IQ tests, individuals with a broad range of life experiences varying performance on these tests which then reflect the types of knowledge one is exposed to during the course of their lives. So knowing what we know about blacks and whites being different cultural groups, and what we know about different cultures having different knowledge bases, then we can rightly state that disparities in IQ scores between blacks and whites are suggested to be due to environmental factors.

Unequal exposure to information creates divergent knowledge bases which then influence the score on the test of knowledge (IQ test). And since we now know that despite initial differences in initial performance that students have a surprising regularity in learning rates, this suggests that once exposed to information, the rate of knowledge acquisition remains consistent across individuals which then challenges the assumption of innate disparities in learning abilities. So the sociocultural context becomes pivotal in shaping the kinds of knowledge that people are exposed to. Cultural tools environmental factors and social interactions contribute to diverse cognitive abilities and knowledge domains which then emphasize the contextual nature of not only intelligence but performance in IQ tests. So what this shows is that test scores are reflective of the kinds of experience the testee was exposed to. So disparities in test scores therefore indicate differences in learning opportunities and cultural contexts

So a conclusive rejection of Jensen’s default hypothesis asserts that the black-white IQ gap is due to exposure to different types of knowledge. Thus, what explains disparities in not only blacks and whites but between groups is unequal opportunities to exposure of information—most importantly the type of information found on IQ tests. My sociocultural theory of knowledge acquisition and crystalization offers a compelling counter to hereditarian perspectives, and asserts that diverse experiences and intentionality learning efforts contribute to cognitive development. The claim that all groups or individuals are exposed to similar types of knowledge as Jensen assumes is false. By virtue of being different groups, they are exposed to different knowledge bases. Since this is true, and IQ tests are culture-bound and tests of a certain kind of knowledge, then it follows that what explains group differences in IQ and knowledge would therefore be differences in exposure to information.

Rushton, Race, and Twinning

2500 words

As is the case with the other lines of evidence that intend to provide sociobiological evidence in support of the genetic basis of human behavior and development (relating to homology, heritability, and adaptation), Rushton’s work reduces to no evidence at all. (Lerner, 2018)

Introduction

From 1985 until his death in 2012, J. P. Rushton attempted to marshal all of the data and support he could for a theory called r-K selection theory or Differential K theory (Rushton, 1985). The theory posited that while humans were the most K species of all, some human races were more K than others, so it then followed that some human races were more r than others. Rushton then collated mass amounts of data and wrote what would become his magnum opus, Race, Evolution and Behavior (Rushton, 1997). So in the r/K theory first proposed by MacArthur and Wilson, unstable, unpredictable environments favored an r strategy whereas a stable, predictable environments favored a K strategy. (See here for my response to Rushton’s r/K.)

So knowing this, one of the suite of traits Rushton put on his r/K matrix was twinning rates. Rushton (1997: 6) stated:

the rate of dizygotic twinning, a direct index of egg production, is less than 4 per 1,000 births among Mongoloids, 8 per 1,000 among Caucasoids, and 16 or greater per 1,000 among Negroids.

I won’t contest the claim that the rate in DZ twinning is higher by race—because it’s pretty well-established with recent data that blacks are more likely to have twins than whites (that is, blacks have a slightly higher chance of having twins than whites, who have a slightly higher chance of having twins than Asians) (Santana, Surita, and Cecatti, 2018; Wang, Dongarwar, and Salihu, 2020; Monden, Pison, and Smits, 2021)—I’m merely going to contest the causes of DZ twinning. Because it’s clear that Rushton was presuming this to be a deeply evolutionary trait since a highs rate of twins—in an evolutionary context—would mean that there would be a higher chance for children of a particular family to survive and therefore spread their genes and thusly would, in his eyes, lend credence to his claim that Africans were more r compared to whites who were more r compared to Asians.

But to the best of my knowledge, Rushton didn’t explain why, biologically, blacks would have more twins than whites—he merely said “This race has more twins than this race, so this lends credence to my theory.” That is, he didn’t posit a biological mechanism that would instantiate a higher rate of twinning in blacks compared to whites and Asians and then explain how environmental effects wouldn’t have any say in the rate of twinning between the races. However, I am privy to environmental factors that would lead to higher rates of twinning and I am also privy to the mechanisms of action that allow twinning to occur (eg phytoestrogens, FSH, LH, and IGF). And while these are of course biological factors, I will show that there are considerable effects of environmental interactions like diet on the levels of these hormones which are associated with twinning. I will also explain how these hormones are related to twinning.

While the claim that there is a difference in rate of DZ twinning by race seems to be true, I don’t think it’s a biological trait, nevermind an evolutionary one as Rushton proposed (because even if Rushton’s r/K were valid, “Negroids” would be K and “Mongoloids” would be r, Anderson, 1991). Nonetheless, Rushton’s r/K theory is long-refuted, though he did call attention to some interesting observations (which other researchers never ignored, they just didn’t attempt some grand theory of racial differences).

Follicle stimulating hormone, leutinizing hormone, and insulin-like growth factor

We know that older women are more likely to have twins while younger women are less likely (Oleszczuk et al, 2001), so maternal age is a factor. As women age, a hormone called follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) increases due to a decline in estrogen, and it is one of the earliest signs of female reproductive aging (McTavish et al, 2007), being one of the main biomarkers of ovarian reserve tested on day 3 of the menstrual cycle (Roudebush, Kivens, and Mattke, 2008). It is well established that twinning is different in different geographic locations, that the rate of MZ twins is constant at around 3.5 to 4 per 1,000 births (so what is driving the differences is the birth of DZ twins), and that it increases due to an increase in FSH (Santana, Surita, and Cecatti, 2018). We also know that pre-menopausal women who have given birth to DZ twins have higher levels of FSH on the third day of their menstrual cycle (Lambalk et al, 1998).

So if FSH levels stay too high for too long then multiple eggs are released, which could lead to an increase in DZ twinning. FSH stimulates the maturation and growth of ovarian follicles, each of which contains an immature egg called an oocyte. FSH acts on the ovaries to promote the development of multiple ovarian follicles during pregnancy, a process which is called recruitment. In a normal menstrual cycle, only one follicle is stimulated to release one egg; but when FSH levels are elevated, this results in the development and maturation of more than one follicle which is known as polyovulation. Polyovulation then increases the chance of the release of multiple eggs during ovulation. Thus, if more than one egg is released during a menstrual cycle, and they both are fertilized, it can then lead to the development of DZ twins.

Along with FSH, we also have luetenizing hormone (LH). So FSH and LH act synergistically (Raju et al, 2013). LH, like FSH, isn’t directly responsible for the increase in twinning, but the process that it allows (playing a role in ovulation) is a crucial factor in twinning. So LH is responsible for triggering ovulation, which is the release of a mature egg from the ovarian follicle. (Ovulation occurs typically 24 to 36 hours after LH increases.) In a typical menstrual cycle, only one follicle is stimulated to release one egg, which is triggered by the surge in LH. But if there are multiple mature follies in the ovaries (which could be influenced by FSH), then a surge in LH can lead to the release of more than one egg. So the interaction of LH with other hormone like FSH, along with the presence of multiple mature follicles, can be associated with having a higher chance of having DZ twins. FSH therapies are also used in assisted reproduction (eg Munoz et al, 1995 in mice; Ferraretti et al, 2004; Pang, 2005; Pouwer, Farquhar, and Kremer, 2015; Fatemi et al, 2021).

So when it comes to FSH, we know that malnutrition may play a role in twinning, and also that wild yams—a staple food in Nigeria—increases phytoestrogens which increase FSH in the body of women (Bartolus, et al, 1999). Wild yams have been used to increase estrogen in women’s bodies (due to the phytoestrogens they contain), and it enhances estradiol through the mechanism of binding to estrogen receptor sites (Hywood, 2008). And since Nigeria has the highest rate of twinning in the world (Santana, Surita, and Cecatti, 2018), and their diet is wild yam-heavy (Bartolus, et al, 1999), it seems that this fact would go a long way in explaining why they have higher rates of twinning. Mount Sinai says that “Although it does not seem to act like a hormone in the body, there is a slight risk that wild yam could produce similar effects to estrogen.” It acts as a weak phytoestrogen (Park et al, 2009). (But see Beckham, 2002.) But when phytoestrogens are consumed, they can then bind to estrogen receptors in the body and trigger estrogenic effects which could then lead to the potential stimulation and release of multiple eggs which would increase the chance of DZ twinning.

One study showed that black women, in comparison to white women, had “lower follicular phase LH:FSH ratios” (Reuttman et al, 2002; cf Marsh et al, 2011), while Randolph et al (2004) showed that black women had higher FSH than Asian and white women. So the lower LH:FSH ratio could affect the timing and regulation of ovulation, and a lower LH:FSH level could reduce the chances of premature ovulation and could affect the release of multiple eggs.

Lastly, when it comes to insulin-like growth factor (IGF), this could be influenced by a high protein diet or a high carb diet. Diets high in high glycemic carbs can lead to increase insulin production which would then lead to increased IGF levels. Just like with FSH and LH, increased levels of IGF could also in concert with the other two hormones influence the maturation and release of multiple eggs during a menstrual cycle which would then increase the chance of twinning (Yoshimura, 1998). IGF can also stimulate the growth and development of multiple follicles (Stubbs et al, 2013) and have them mature early if IGF levels are high enough (Mazerbourgh and Monget, 2018). This could then also lead to polyovulation, triggering the release of more than one egg during ovulation. IGF can also influence the sensitivity of the ovaries to hormonal signals, like those from the pituitary gland, which then leads to enhanced ovarian sensitivity to hormones like FSH and LH which then, of course, would act synergistically increasing the rate of dizygotic twinning. (See Mazerbourgh and Monget, 2018 for a review of this.)

So we know that black women have higher levels of IGF-1 and free IGF-1—but lower IGF-2 and IGFBP-3—than white women (Berrigan et al, 2010; Fowke et al, 2011). The higher IGF-1 levels in black women could lead to increase ovarian sensitivity to FSH and LH, and thus enhanced ovarian sensitivity could lead to the promotion and release of multiple eggs during ovulation. The lower IGF-2 levels could contribute to the balance of IGF-1 and IGF-2, which would then further influence the ovarian sensitivity to other hormones. IGFBP-3 is a binding protein which regulated the bioavailability of IGF-1, so lower levels of IGFBP-3 could lead to higher concentrations of free IGF-1, which would then further stimulate the ovarian follicles and could lead to polyovulation, leading to increased twinning. Though there is some evidence that this difference does have a “genetic basis” (Higgins et al, 2005), we know that dietary factors do have an effect on IGF levels (Heald et al, 2003).

Rushton’s misinterpretations

Rushton got a ton wrong, but he was right about some things too (which is to be expected if you’re looking to create some grand theory of racial differences). I’m not too worried about that. But what I AM worried about, is Rushton’s outright refusal to address his most serious critics in the literature, most importantly Anderson (1991) and Graves (2002 a, b). If you check his book (Rushton, 1997: 246-248), his responses are hardly sufficient to address the devestating critiques of his theory. (Note how Rushton never responded to Graves, 2002—ever.) Gorey and Cryns (1995) showed how Rushton cherry-picked what he liked for his theory while stating that “any behavioral differences which do exist between blacks, whites and Asian Americans for example, can be explained in toto by environmental differences which exist between them” while Ember, Ember, and Peregrine (2003) concluded similarly. (Rushton did respond to Gorey and Cryns, but not Ember, Ember, and Peregrine.) Cernovsky and Littman (2019) also showed how Rushton cherry-picked his INTERPOL crime data.

Now that I have set the stage for Rushton’s “great” scholarship, let’s talk about the response he got to his twinning theory.

Allen et al (1992) have a masterful critique of Rushton’s twinning theory. They review twinning stats in other countries across different time periods and come to conclude that “With such a wide overlap between races, and such great variation within races, twinning rate is probably no better than intelligence as an index of genetic status for racial groups.” They also showed that the twinning mechanism didn’t seem to be a relevant factor in survival, until the modern day with the advancement of our medical technologies, that is. So since twinning increases the risk for death in the mother (Steer, 2007; Santana et al, 2018). Rushton also misinterpreted numerous traits associated with twinning:

individual twin proneness and its correlates do not provide Rushton’s desired picture of a many-faceted r- strategy (even if such individual variation could have evolutionary meaning). With the exception of shorter menstrual cycles found in one study, the traits Rushton cites as r-selected in association with twinning are either statistical artifacts of no reproductive value or figments of misinterpretation.

Conclusion

I have discussed a few biological variables that lead to higher rates of twinning and I have cited some research which shows that black women have higher rates of some of the hormones that are related to higher rates of twinning. But I have also shown that it’s not so simple to jump to a genetic conclusion, since these hormones are of course mediated by environmental factors like diet.

Rushton quite clearly takes these twinning rate differences to be “genetic” in nature, but we are in the 2020s now, not the 1980s, and we now know that genes are necessary, but passive players in the formation of phenotypes (Noble, 2011, 2012, 2016; Richardson, 2017, 2021; Baverstock, 2021; McKenna, Gawne, and Nijhout, 2022). These new ways of looking at genes—as passive, not active causes, and as not special from any other developmental resources—shows how the reductionist thinking of Rushton and his contemporaries were straight out false. Nonetheless, while Rushton did get it right that there is a racial difference in twinning, the difference, I think, isn’t a genetic difference and I certainly don’t think they it lends credence to his Differential K theory, since Anderson showed that if we were to accept Rushton’s premises, then African would be K and Asians would be r. So while there also are differences in menarche between blacks and whites, this too also seems to be environmentally driven.

Rushton’s twinning thesis was his “best bet” at attempting to show that his r/K theory was “right” about racial differences. But the numerous devestating critiques of not only Rushton’s thesis on twinning but his r/K Differential K theory itself shows that Rushton was merely a motivated reasoner (David Duke also consulted with Rushton when Duke wrote his book My Awakening, where Duke describes how psychologists led to his “racial awakening”), so “The claim that Rushton was acting only as a scientist is not credible given this context” (Winston, 2020). Even the usefulness of psychometric life history theory has been recently questioned (this derives from Rushton’s Differential K, Sear, 2020).

But it is now generally accepted that Rushton’s r/K and the current psychometric life history theory that rose from the ashes of Rushton’s theory just isn’t a good way to conceptualize how humans live in the numerous biomes we live in.

Racial Differences in Motor Development: A Bio-Cultural View of Motor Development

3050 words

Introduction

Psychologist J. P. Rushton was perhaps most famous for attempting to formulate a grand theory of racial differences. He tried to argue that, on a matrix of different traits, the “hierarchy” was basically Mongoloids > Caucasoids > Negroids. But Rushton’s theory was met with much force, and many authors in many of the different disciplines in which he derived his data to formulate his theory attacked his r/K selection theory also known as Differential K theory (where all humans are K, but some humans are more K than others, so some humans are more r than others). Nonetheless, although his theory has been falsified for many decades, did he get some things right about race? Well, a stopped clock is right twice a day, so it wouldn’t be that outlandish to believe that Rushton got some things right about racial differences, especially when it comes to physical differences. While we can be certain that there are physical differences in groups we term “racial groups” and designate “white”, “black”, “Asian”, “Native American”, and “Pacific Islander” (the five races in American racetalk), this doesn’t lend credence to Rushton’s r/K theory.

In this article, I will discuss Rushton’s claims on motor development between blacks and whites. I will argue that he basically got this right, but it is of no consequence to the overall truth of his grand theory of racial differences. We know that there are physical differences between racial groups. But that there are physical differences between racial groups doesn’t entail that Rushton’s grand theory is true. The only entailment, I think, that can be drawn from that is there is a possibility that physical differences between races could exist between them, but it is a leap to attribute these differences to Rushton’s r/K theory, since it is a falsified theory on logical, empirical and methodological grounds. So I will argue that while Rushton got this right, a stopped clock is right twice a day but this doesn’t mean that his r/K theory is true for human races.

Was Rushton right? Evaluating newer studies on black-white motor development

Imagine three newborns: one white, one black and the third Asian and you observe the first few weeks of their lives. Upon observing the beginnings of their lives, you begin to notice differences in motor development between them. The black infant is more motorically advanced than the white infant who is more motorically advanced than the Asian infant. The black infant begins to master movement, coordination and dexterity showing a remarkable level of motoric dexterity, while the white infant shows less motoric dexterity than the black infant, and the Asian infant still shows lower motoric dexterity than the white infant.

These disparities in motor development are evidence in the early stages of life, so is it genetic? Cultural? Bio-cultural? I will argue that what explains this is a bio-cultural view, and so it will of course eschew reductionism, but of course as infants grow and navigate through their cultural milieu and family lives, this will have a significant effect on their experiences and along with it their motoric development.

Although Rushton got a lot wrong, it seems that he got this issue right—there does seem to be differences in precocity of motor development between the races, and the references he cites below in his 2000 edition of Race, Evolution, and Behavior—although most are ancient compared to today’s standards—hold to scrutiny today, where blacks walk earlier than whites who walk earlier than Asians.

Rushton (2000: 148-149) writes:

Revised forms of Bayley’s Scales of Mental and Motor Development administered in 12 metropolitan areas of the United States to 1,409 representative infants aged 1-15 months showed black babies scored consistently above whites on the Motor Scale (Bayley, 1965). This difference was not limited to any one class of behavior, but included: coordination (arm and hand); muscular strength and tonus (holds head steady, balances head when carried, sits alone steadily, and stands alone); and locomotion (turns from side to back, raises self to sitting, makes stepping movements, walks with help, and walks alone).

Similar results have been found for children up to about age 3 elsewhere in the United States, in Jamaica, and in sub-Saharan Africa (Curti, Marshall, Steggerda, & Henderson, 1935; Knobloch & Pasamanik, 1953; Williams & Scott, 1953; Walters, 1967). In a review critical of the literature Warren (1972) nonetheless reported evidence for African motor precocity in 10 out of 12 studies. For example, Geber (1958:186) had examined 308 children in Uganda and reported an “all-round advance of development over European standards which was greater the younger the child.” Freedman (1974, 1979) found similar results in studies of newboms in Nigeria using the Cambridge Neonatal Scales (Brazelton & Freedman, 1971).

Mongoloid children are motorically delayed relative to Caucasoids. In a series of studies carried out on second- through fifth-generation Chinese-Americans in San Francisco, on third- and fourth-generation Japanese-Americans in Hawaii, and on Navajo Amerindians in New Mexico and Arizona, consistent differences were found between these groups and second- to fourth-generation European-Americans using the Cambridge Neonatal Scales (Freedman, 1974, 1979; Freedman & Freedman, 1969). One measure involved pressing the baby’s nose with a cloth, forcing it to breathe with its mouth. Whereas the average Chinese baby fails to exhibit a coordinated “defense reaction,” most Caucasian babies turn away or swipe at the cloth with the hands, a response reported in Western pediatric textbooks as the normal one.

On other measures including “automatic walk,” “head turning,” and “walking alone,” Mongoloid children are more delayed than Caucasoid children. Mongoloid samples, including the Navajo Amerindians, typically do not walk until 13 months, compared to the Caucasian 12 months and Negro 11 months (Freedman, 1979). In a standardization of the Denver Developmental Screening Test in Japan, Ueda (1978) found slower rates of motoric maturation in Japanese as compared with Caucasoid norms derived from the United States, with tests made from birth to 2 months in coordination and head lifting, from 3 to 5 months in muscular strength and rolling over, at 6 to 13 months in locomotion, and at 15 to 20 months in removing garments.

Regarding newer studies on this matter, there are differences between European and Asian children in the direction that Rushton claimed. Infants from Hong Kong displayed a difference sequence of rolling compared to Canadian children. There does seem to be a disparity in motoric development between Asian and white children (Mayson, Harris, and Bachman, 2007). These authors do cite some of the same studies like the DDST (which is currently outdated) which showed how Asian children were motorically delayed compared to white children. And although they put caution on their findings of their literature review, it’s quite clear that this pattern exists and it is a bio-cultural one. So they conclude their literature review writing “the literature reviewed suggests differences in rate of motor development among children of various ethnic origins, including those of Asian and European descent” and that “Limited support suggests also that certain developmental milestones, such as rolling, may differ between infants of Asian and European origin.” Further, cultural practices in northern China—for example, lying them on their backs on sandbags—stall the onset of walking in babies sitting, crawling, and walking by a few months (Karasik et al, 2011).