Home » Race Realism (Page 9)

Category Archives: Race Realism

Just-so Stories: MCPH1 and ASPM

1350 words

“Microcephalin, a gene regulating brain size, continues to evolved adaptively in humans” (Evans et al, 2005) “Adaptive evolution of ASPM, a major determinant of cerebral cortical size in humans” (Evans et al, 2004) are two papers from the same research team which purport to show that both MCPH1 and ASPM are “adaptive” and therefore were “selected-for” (see Fodor, 2008; Fodor and Piatteli-Palmarini, 2010 for discussion). That there was “Darwinian selection” which “operated on” the ASPM gene (Evans et al, 2004), that we identified it was selected, along with its functional effect is evidence that it was supposedly “selected-for.” Though, the combination of functional effect along with signs of (supposedly) positive selection do not license the claim that the gene was “selected-for.”

One of the investigators who participated in these studies was one Bruce Lahn, who stated in an interview that MCPH1 “is clearly favored by natural selection.” Evans et al (2005) show specifically that the variant supposedly under selection (MCPH1) showed lower frequencies in Africans and the highest in Europeans.

But, unfortunately for IQ-ists, neither of these two alleles are associated with IQ. Mekel-Boborov et al (2007: 601) write that their “overall findings suggest that intelligence, as measured by these IQ tests, was not detectably associated with the D-allele of either ASPM or Microcephalin.” Timpson et al (2007: 1036A) found “no meaningful associations with brain size and various cognitive measures, which indicates that contrary to previous speculations, ASPM and MCPH1 have not been selected for brain-related effects” in genotyped 9,000 genotyped children. Rushton, Vernon, and Bons (2007) write that “No evidence was found of a relation between the two candidate genes ASPM and MCPH1 and individual differences in head circumference, GMA or social intelligence.” Bates et al’s (2008) analysis shows no relationship between IQ and MCPH1-derived genes.

But, to bring up Fodor’s critique, if MCPH1 is coextensive with another gene, and both enhance fitness, then how can there be direct selection on the gene in question? There is no way for selection to distinguish between the two linked genes. Take Mekel-Bobrov et al (2005: 1722) who write:

The recent selective history of ASPM in humans thus continues the trend of positive selection that has operated at this locus for millions of years in the hominid lineage. Although the age of haplogroup D and its geographic distribution across Eurasia roughly coincide with two important events in the cultural evolution of Eurasia—namely, the emergence and spread of domestication from the Middle East ~10,000 years ago and the rapid increase im population associated with the development of cities and written language 5000 to 6000 years ago around the Middle East—the signifigance of this correlation is not clear.

Surely both of these genetic variants have a hand in the dawn of these civilizations and behaviors of our ancestors; they are correlated, right? Though, they only did draw that from the research studies they reported on—these types of wild speculation are in the papers referenced above. Lahn and his colleagues, though, are engaging in very wild speculation—if these variants are under positive selection, that is.

So it seems that this research and the conclusions drawn from it are ripe for a just-so story. We need to do a just-so story check. Now let’s consult Smith’s (2016: 277-278) seven just-so story triggers:

1) proposing a theory-driven rather than a problem-driven explanation, 2) presenting an explanation for a change without providing a contrast for that change, 3) overlooking the limitations of evidence for distinguishing between alternative explanations (underdetermination), 4) assuming that current utility is the same as historical role, 5) misusing reverse engineering, 6) repurposing just-so stories as hypotheses rather than explanations, and 7) attempting to explain unique events that lack comparative data.

For example, take (1): a theory-driven explanation leads to a just-so story, as Shapiro (2002: 603) notes, “The theory-driven scholar commits to a sufficient account of a phenomenon, developing a “just so” story that might seem convincing to partisans of her theoretical priors. Others will see no more reason to believe it than a host of other “just so” stories that might have been developed, vindicating different theoretical priors.” That these two genes were “selected-for” means that, for Evans et al, it is a theory-driven explanation and therefore falls prey to the just-so story criticism.

Rasmus Nielsen (2009) has a paper on the thirty years of adaptationism after Gould and Lewontin’s (1972) Spandrels paper. In it, he critiques so-called examples of two genes being supposedly selected-for: a lactase gene, and MCPH1 and ASPM. Nielsen (2009) writes of MCPH1 and ASPM:

Deleterious mutations in ASPM and microcephalin may lead to reduced brain size, presumably because these genes are cell‐cycle regulators and very fast cell division is required for normal development of the fetal brain. Mutations in many different genes might cause microcephaly, but changes in these genes may not have been the underlying molecular cause for the increased brain size occurring during the evolution of man.

In any case, Currat et al (2006: 176a) show that “the high haplotype frequency, high levels of homozygosity, and spatial patterns observed by Mekel-Bobrov et al. (1) and Evans et al. (2) can be generated by demographic models of human history involving a founder effect out-of-Africa and a subsequent demographic or spatial population expansion, a very plausible scenario (5). Thus, there is insufficient evidence for ongoing selection acting on ASPM and microcephalin within humans.” McGowen et al (2011) show that there is “no evidence to support an association between MCPH1 evolution and the evolution of brain size in highly encephalized mammalian species. Our finding of significant positive selection in MCPH1 may be linked to other functions of the gene.”

Lastly, Richardson (2011: 429) writes that:

The force of acceptance of a theoretical framework for approaching the genetics of human intellectual differences may be assessed by the ease with which it is accepted despite the lack of original empirical studies – and ample contradictory evidence. In fact, there was no evidence of an association between the alleles and either IQ or brain size. Based on what was known about the actual role of the microcephaly gene loci in brain development in 2005, it was not appropriate to describe ASPM and microcephalin as genes controlling human brain size, or even as ‘brain genes’. The genes are not localized in expression or function to the brain, nor specifically to brain development, but are ubiquitous throughout the body. Their principal known function is in mitosis (cell division). The hypothesized reason that problems with the ASPM and microcephalin genes may lead to small brains is that early brain growth is contingent on rapid cell division of the neural stem cells; if this process is disrupted or asymmetric in some way, the brain will never grow to full size (Kouprina et al, 2004, p. 659; Ponting and Jackson, 2005, p. 246)

Now that we have a better picture of both of these alleles and what they are proposed to do, let’s now turn to Lahn’s comments on his studies. Lahn, of course, commented on “lactase” and “skin color” genes in defense of his assertion that such genes like ASPM and MCPH1 are linked to “intelligence” and thusly were selected-for just that purpose. However, as Nielsen (2009) shows, that a gene has a functional effect and shows signs of selection does not license the claim that the gene in question was selected-for. Therefore, Lahn and colleagues engaged in fallacious reasoning; they did not show that such genes were “selected-for”, while even studies done by some prominent hereditarians did not show that such genes were associated with IQ.

Like what we now know about the FOXP2 gene and how there is no evidence for recent positive or balancing selection (Atkinson et al, 2018), we can now say the same for such other evolutionary just-so stories that try to give an adaptive tinge to a trait. We cannot confuse selection and function as evidence for adaptation. Such just-so stories, like the one described above along with others on this blog, can be told about any trait or gene and explain why it was selected and stabilized in the organism in question. But historical narratives may be unfalsifiable. As Sterelny and Griffiths write in their book Sex and Death:

Whenever a particular adaptive story is discredited, the adaptationist makes up a new story, or just promises to look for one. The possibility that the trait is not an adaptation is never considered.

“Mongoloid Idiots”: Asians and Down Syndrome

1700 words

Look at a person with Down Syndrome (DS) and then look at an Asian. Do you see any similarities? Others, throughout the course of the 20th century have. DS is a disorder arising from chromosomal defects which causes mental and physical abnormalities, short stature, broad facial profile, and slanted eyes. Most likely, one suffering from DS has an extra copy of chromosome 21—which is why the disorder is called “trisomy 21” in the scientific literature.

I am not aware if most “HBDers” know this, but Asians in America were treated similarly to blacks in the mid-20th century (with similar claims made about genital and brain size). Whites used to be said to have the biggest brains out of all of the races but this changed sometime in the 20th century. Lieberman (2001: 72) writes that:

The shrinking of “Caucasoid” brains and cranial size and the rise of “Mongoloids” in the papers of J. Philippe Rushton began in the 1980s. Genes do not change as fast as the stock market, but the idea of “Caucasian” superiority seemed contradicted by emerging industrialization and capital growth in Japan, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Singapore, and Korea (Sautman 1995). Reversing the order of the first two races was not a strategic loss to raciocranial hereditarianism, since the major function of racial hierarchies is justifying the misery and lesser rights and opportunities of those at the bottom.

So Caucasian skulls began to shrink just as—coincidentally, I’m sure—Japan began to get out of its rut it got into after WWII. Morton noted that Caucasians had the biggest brains with Mongoloids in the middle and Africans with the smallest—then came Rushton to state that, in fact, it was East Asians who had the bigger brains. Hilliard (2012: 90-91) writes:

In the nineteenth century, Chinese, Japanese, and other Asian males were often portrayed in the popular press as a sexual danger to white females. Not surprising, as Lieberman pointed out, during this era, American race scientists concluded that Asians had smaller brains than whites did. At the same time, and most revealing, American children born with certain symptoms of mental retardation during this period were labeled “mongoloid idiots.” Because the symptoms of this condition, which we now call Down Syndrome, includes “slanting” eyes, the old label reinforced prejudices against Asians and assumptions that mental retardation was a peculiarly “mongoloid” racial characteristic.

[Hilliard also notes that “Scholars identified Asians as being less cognitively evolved and having smaller brains and larger penises than whites.” (pg 91)]

So, views on Asians were different back in the 19th and 20th centuries—it even being said that Asians had smaller brains and bigger penises than whites (weird…).

Mafrica and Fodale (2007) note that the history of the term “mongolism” began in 1866, with the author distinguishing between “idiotis”: the Ethiopian, the Caucasian, and the Mongoloid. What led Langdon (the author of the 1866 paper) to make this comparison was the almond-shaped eyes that DS people have as well. Though Mafrica and Fodale (2007: 439) note that it is possible that other traits could have forced him to make the comparison, “such as fine and straight hair, the distribution of apparatus piliferous, which appears to be sparse.” Mafrica and Fodale (2007: 439) also note more similarities between people with DS and Asians:

Down persons during waiting periods, when they get tired of standing up straight, crouch, squatting down, reminding us of the ‘‘squatting’’ position described by medical semeiotic which helps the venous return. They remain in this position for several minutes and only to rest themselves this position is the same taken by the Vietnamese, the Thai, the Cambodian, the Chinese, while they are waiting at a the bus stop, for instance, or while they are chatting.

There is another pose taken by Down subjects while they are sitting on a chair: they sit with their legs crossed while they are eating, writing, watching TV, as the Oriental peoples do.

Another, funnier, thing noted by Mafrica and Fodale (2007) is that people with DS may like to have a few plates across the table, while preferring foodstuffs that is high in MSG—monosodium glutamate. They also note that people with DS are more likely to have thyroid disorders—like hypothyroidism. There is an increased risk for congenital hypothyroidism in Asian families, too (Rosenthal, Addison, and Price, 1988). They also note that people with DS are likely “to carry out recreative–reabilitative activities, such as embroidery, wicker-working ceramics, book-binding, etc., that is renowned, remind the Chinese hand-crafts, which need a notable ability, such as Chinese vases or the use of chop-sticks employed for eating by Asiatic populations” (pg 439). They then state that “it may be interesting to know the gravity with which the Downs syndrome occurs in Asiatic population, especially in Chinese population.” How common is it and do they look any different from other races’ DS babies?

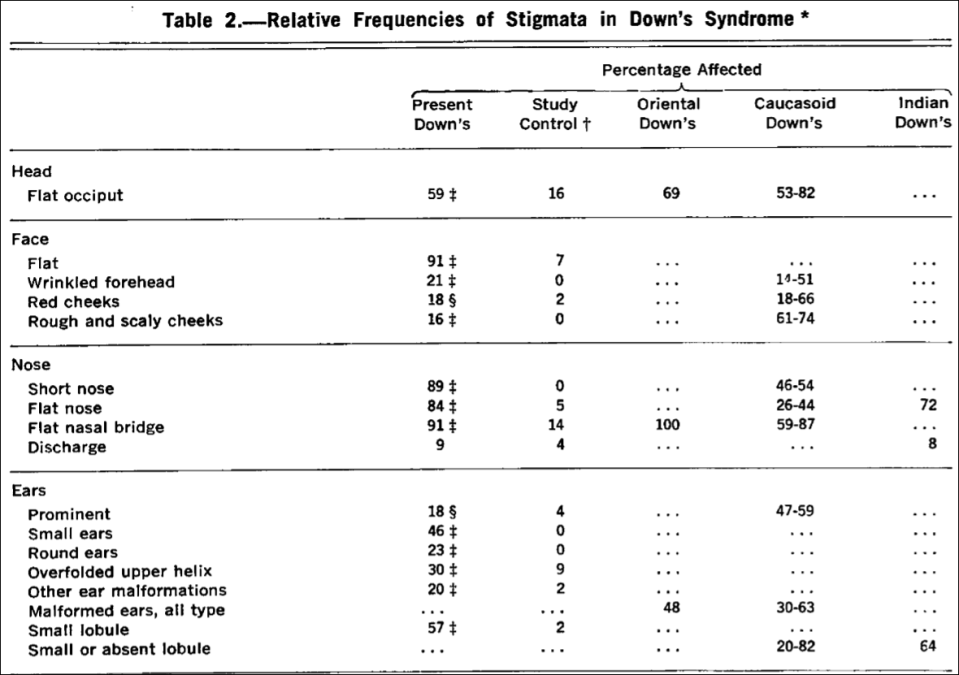

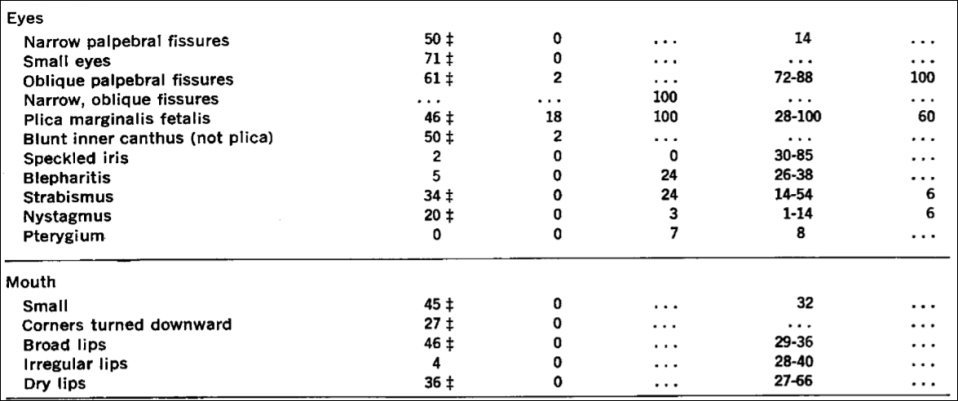

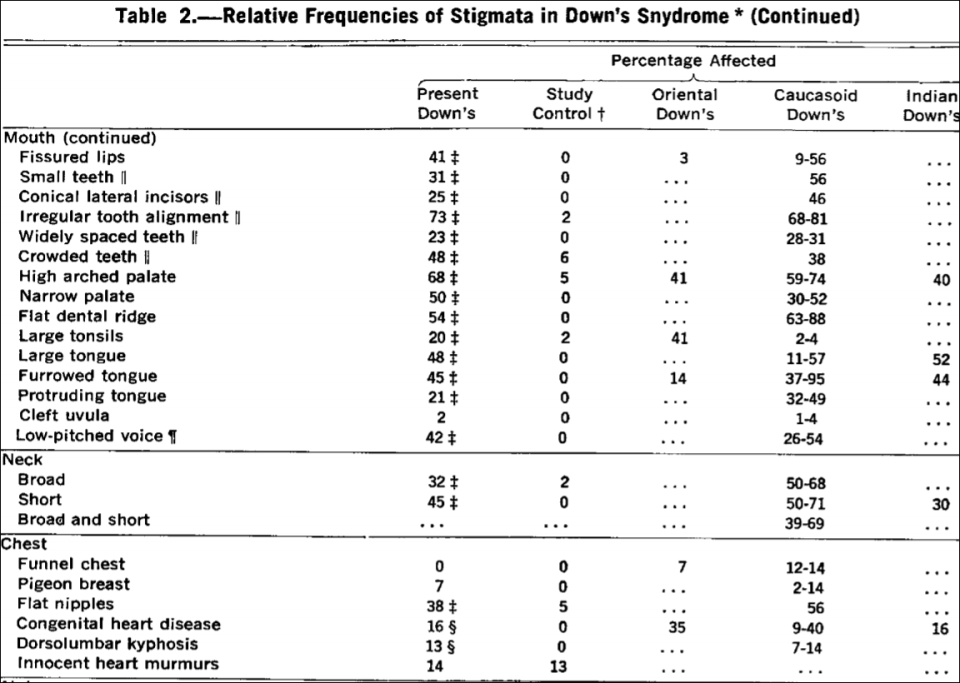

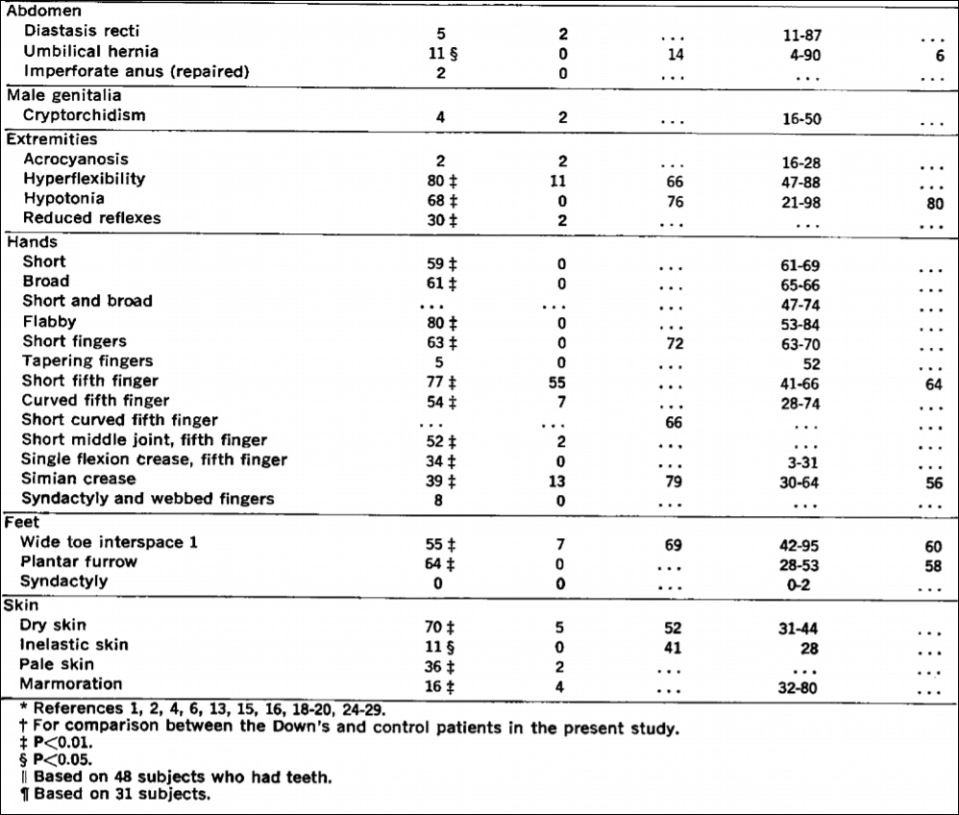

See, e.g., Table 2 from Emanuel et al (1968):

Emanuel et al (1968: 465) write that “Almost all of the stigmata of Down’s syndrome presented in Table 2 appear also to be of significance in this group of Chinese patients. The exceptions have been reported repeatedly, and they all probably occur in excess in Down’s syndrome.”

Examples such as this are great to show the contingencies of certain observations—like with racial differences in “intelligence.” Asians, today, are revered for “hard work”, being “very intelligent” and having “low crime rates.” But, even as recently as the mid 20th century—going back to the mid 18th century—Asians (or Mongoloids, as Rushton calls them) were said to have smaller brains and larger penises. Anti-miscegenation laws held for Asians, too of course, and so interracial marriage was forbidden with Asians and whites which was “to preserve the ‘racial integrity’ of whites” (Hilliard, 2012: 91).

Hilliard (2012) states that the effeminate, small-penis Asian man. Hilliard (2012: 86) writes:

However, it is also possible that establishing the racial supremacy of whites was not what drove this research on racial hierarchies. If so, the IQ researchers were probably justified in protesting their innocence, at least in regard to the charge of being racial supremacists, for in truth, the Asians’ top ranking might have unintentionally underscored that true sexual preoccupations underlying this research in the first place. It not seems that the real driving force behind such work was not racial bigotry so much as it was the masculine insecurities emanating from the unexamined sexual stereotypes still present within American popular culture. Scholars such as Rushton, Jensen, and Herrnstein provided a scientific vocabulary and mathematically dense charts and graphs to give intellectual polish to the preoccupations. Thus, it became useful to tout the Asians’ cognitive superiority but only so long as whites remained above blacks in the cognitive hierarchy.

Of course, by switching the racial hierarchy—but keeping the bottom the same—IQ researchers can say “We’re not racists! If we were, why would we state that Asians were better on trait T than we were!”, as has been noted by John Relethford (2001: 84) who writes that European-descended researchers “can now deflect charges of racism or ethnocentrism by pointing out that they no longer place themselves at the top. Lieberman aptly notes that this shift does not affect the major focus of many ideas regarding racial superiority that continue to place people of recent African descent at the bottom.” While biological anthropologist Fatima Jackson (2001: 83) states that “It is deemed acceptable for “Mongoloids” to have larger brains and better performance on intelligence tests than “Caucasoids,” since they are (presumably) sexually and reproductively compromised with small genitalia, low fertility, and delayed maturity.”

The main thesis of Straightening the Bell Curve is that preoccupations with brain and genital size is a driving part of these psychologists who study racial differences. Stating that Asians had smaller penises but larger heads though they were less likely to like sex while blacks had larger penises, smaller heads and were more likely to like sex while whites were, like Goldilocks, juuuuuust right—a penis size in-between Asians and blacks and a brain neither too big or too small. So, stating that X race had smaller brains and bigger penises seems, as Hilliard argues, to be a coping mechanism for certain researchers and to drive women away from that racial group.

In any case, how weird it is for Asians (“Mongoloids”) to be ridiculed as having small brains and large penises (a hilarious reversal of Rushton’s r/K bullshit) and then—all of a sudden—for them to come out on top over whites while whites are still over blacks in this racial hierarchy. How weird is it for the placements to change with certain economic events in a country’s history. Though, as many authors have noted, for instance Chua (1999), Asian men have faced emasculinazation and femininzation in American society. So, since they were seen to be “undersexed, they were thus perceived as minimal rivals to white men in the sexual competition for women” (Hilliard, 2012: 87).

So, just like the observation of racial/country IQ are contingent on the time and the place of the observation, so too is the observation of racial differences in certain traits and how they can be used for a political agenda. As Constance Hilliard (2012: 85) writes, referring to Professor Michael Billig’s article A dead idea that will not lie down (in reference to race science), “… scientific ideas did not develop in a vacuum but rather reflected underlying political and economic trends.“ And so, this is why “mongoloid idiots” and undersexed Asians appeared in American thought in the mid-20th century. So these ideas noted here—mongloidism, undersexed Asians, small penis, large penis, small brain, large brained Asians (based on the time and the place of the observation) show, again, the contingency of these racial hierarchies—which, of course, still stay with blacks on the bottom and whites above them. Is it not strange that whites moved a rung down on this hierarchy as soon as Rushton appeared in the picture? (Since, Morton noted that they had smaller heads than Caucasians, Lieberman, 2001.)

The origins of the term “mongloidism” are interesting—especially with how they tie into the origins of the term Down Syndrome and how they related to the “Asian look” along with all of the peculiarities of people with DS and (to Westerners), the peculiarities of Asian living. This is, of course, why one’s political motives, while not fully telling of their objectives and motivations, may—in a way—point one in the right direction as to why they are formulating such hypotheses and theories.

The Argument in The Bell Curve

600 words

On Twitter, getting into discussions with Charles Murray acolytes, someone asked me to write a short piece describing the argument in The Bell Curve (TBC) by Herrnstein and Murray (H&M). This is because I was linking my short Twitter thread on the matter, which can be seen here:

In TBC, H&M argue that America is becoming increasingly stratified by social class, and the main reason is due to the “cognitive elite.” The assertion is that social class in America used to be determined by one’s social origin is now being determined by one’s cognitive ability as tested by IQ tests. H&M make 6 assertions in the beginning of the book:

(i) That there exists a general cognitive factor which explains differences in test scores between individuals;

(ii) That all standardized tests measure this general cognitive factor but IQ tests measure it best;

(iii) IQ scores match what most laymen mean by “intelligent”, “smart”, etc.;

(iv) Scores on IQ tests are stable, but not perfectly so, throughout one’s life;

(v) Administered properly, IQ tests are not biased against classes, races, or ethnic groups; and

(vi) Cognitive ability as measured by IQ tests is substantially heritable at 40-80%/

In the second part, H&M argue that high cognitive ability predicts desireable outcomes whereas low cognitve ability predicts undesireable outcomes. Using the NLSY, H&M show that IQ scores predict one’s life outcomes better than parental SES. All NLSY participants took the ASVAB, while others took IQ tests which were then correlated with the ASVAB and the correlation came out to .81.

They analyzed whether or not one has ever been incarcerated, unemployed for more than one month in the year; whether or not they dropped out of high-school; whether or not they were chronic welfare recipients; among other social variables. When they controlled for IQ in these analyses, most of the differences between ethnic groups, for example, disappeared.

Now, in the most controversial part of the book—the third part—they discuss ethnic differences in IQ scores, stating that Asians have higher IQs than whites who have higher IQs than ‘Hispanics’ who have higher IQs than blacks. H&M argue that the white-black IQ gap is not due to bias since they do not underpredict blacks’ school or job performance. H&M famously wrote about the nature of lower black IQ in comparison to whites:

If the reader is now convinced that either the genetic or environmental explanation has won out to the exclusion of the other, we have not done a sufficiently good job of presenting one side or the other. It seems highly likely to us that both genes and environment have something to do with racial differences. What might the mix be? We are resolutely agnostic on that issue; as far as we can determine, the evidence does not yet justify an estimate.

Finally, in the fourth and last section, H&M argue that efforts to raise cognitive ability through the alteration of the social and physical environment have failed, though we may one day find some things that do raise ability. They also argue that the educational experience in America neglects the small, intelligent minority and that we should begin to not neglect them as they will “greatly affect how well America does in the twenty-first century” (H&M, 1996: 387). They also argue forcefully against affirmative action, in the end arguing that equality of opportunity—over equality of outcome—should be the role of colleges and workplaces. They finally predict that this “cognitive elite” will continuously isolate themselves from society, widening the cognitive gap between them.

JP Rushton: Serious Scholar

1300 words

… Rushton is a serious scholar who has amassed serious data. (Herrnstein and Murray, 1996: 564)

How serious of a scholar is Rushton and what kind of “serious data” did he amass? Of course, since The Bell Curve is a book on IQ, H&M mean that his IQ data is “serious data” (I am not aware of Murray’s views on Rushton’s penis “data”). Many people over the course of Rushton’s career have pointed out that Rushton was anything but a “serious scholar who has amassed serious data.” Take, for example, Constance Hilliard’s (2012: 69) comments on Rushton’s escapades at a Toronto shopping mall where he trolled the mall looking for blacks, whites, and Asians (he payed them 5 dollars a piece) to ask them questions about their penis size, sexual frequency, and how far they can ejaculate:

An estimated one million customers pass through the doors of Toronto’s premier shopping mall, Eaton Centre, in any given week. Professor Jean-Phillipe Rushton sought out subjects in its bustling corridors for what was surely one of the oddest scientific studies that city had known yet—one that asked about males’ penis sizes. In Rushton’s mind, at least, the inverse correlation among races between intelligence and penis size was irrefutable. In fact, it was Rushton who made the now famous assertion in a 1994 interview with Rolling Stone magazine: “It’s a trade-off: more brains or more penis. You can’t have everything. … Using a grant from the conservative Pioneer Fund, the Canadian professor paid 150 customers at the Eaton Centre mall—one-third of whom he identified as black, another third white, and the final third Asian—to complete an elaborate survey. It included such questions such as how far the subject could ejaculate and “how large [is] your penis?” Rushton’s university, upon learning of this admittedly unorthodox research project, reprimanded him for not having the project preapproved. The professor defended his study by insisting that approval for off-campus experiments had never been required before. “A zoologist,” he quipped, “doesn’t need permission to study squirrels in his back yard.” [As if one does not need to get approval from the IRB before undertaking studies on humans… nah, this is just an example of censorship from the Left who want to hide the truth of ‘innate’ racial differences!]

(I wonder if Rushton’s implicit assumption here was that, since the brain takes most of a large amount of our consumed energy to power, that since blacks had smaller brains and larger penises that the kcal consumed was going to “power” their larger penis? The world may never know.)

Imagine you’re walking through a mall with your wife and two children. As your shopping, you see a strange man with a combover, holding measuring tape, approaching different people (which you observe are the three different social-racial groups) asking them questions for a survey. He then comes up to you and your family, pulling you aside to ask you questions about the frequency of the sex you have, how far you can ejaculate and how long your penis is.

Rushton: “Excuse me sir. My name is Jean-Phillipe Rushton and I am a psychologist at the University of Western Ontario. I am conducting a research study, surveying individuals in this shopping mall, on racial differences in penis size, sexual frequency, and how far they can ejaculate.”

You: “Errrrr… OK?”, you say, looking over uncomfortably at your family, standing twenty feet away.

Rushton: “First off, sir, I would like to ask you which race you identify as.”

You: “Well, professor, I identify as black, quote obviously“, as you look over at your wife who has a stern look on her face.

Rushton: “Well, sir, my first question for you is: How far can you ejaculate?”

You: “Ummm I don’t know, I’ve never thought to check. What kind of an odd question is that?“, you say, as you try to keep your voice down as to not alert your wife and children to what is being discussed.

Rushton: “OK, sir. How long would you say your penis is?”

You: “Professor, I have never measured it but I would say it is about 7 inches“, you say, with an uncomfortable look on your face. You think “Why is this strange man asking me such uncomfortable questions?

Rushton: “OK, OK. So how much sex would you say you have with your wife? And what size hat do you wear?“, asked Rushton, it seeming like he’s sizing up your whole body, with a twinkle in his eye.

You: “I don’t see how that’s any of your business, professor. What I do with my wife in the confines of my own home doesn’t matter to you. What does my hat size have to do with anything?”, you say, not knowing Rushton’s ulterior motives for his “study.” “I’m sorry, but I’m going to have to cut this interview short. My wife is getting pissed.”

Rushton: “Sir, wait!! Just a few more questions!”, Rushton says while chasing you with the measuring tape dragging across the ground, while you get away from him as quickly as possible, alerting security to this strange man bothering—harasasing—mall shoppers.

If I was out shopping and some strange man started asking me such questions, I’d tell him tough luck bro, find someone else. (I don’t talk to strange people trying to sell me something or trying to get information out of me.) In any case, what a great methodology, Rushton, because men lie about their penis size when asked.

Hilliard (2012: 71-72) then explains how Rushton used the “work” of the French Army Surgeon (alias Dr. Jacobus X):

Writing under the pseudonym Dr. Jacobus X, the author asserted that it was a personal diary that brought together thirty years of medical practice as a French government army surgeon and physician. Rushton was apparently unaware that the book while unknown to American psychologists, was familiar to anthropologists working in Africa and Asia and that they had nicknamed the genre from which it sprang “anthroporn.” Such books were not actually based on scientific research at all; rather, they were a uniquely Victorian style of pornography, thinly disguised as serious medical field research. Untrodden Fields [the title of Dr. Jacobus X’s book that Rushton drew from] presented Jacobus X’s observations and photographs of the presumably lurid sexual practices of exotic peoples, including photographs of the males’ mammoth-size sexual organs.

[…]

In the next fifteen years, Rushton would pen dozens of articles in academic journals propounding his theories of an inverse correlation among the races between brain and genital size. Much of the data he used to “prove” the enormity of the black male organ, which he then correlated inversely to IQ, came from Untrodden Fields. [Also see the discussion of “French Army Surgeon” in Weizmann et al, 1990: 8. See also my articles on penis size on this blog.]

Rushton also cited “research” from the Penthouse forum (see Rushton, 1997: 169). Citing an anonymous “field surgeon”, the Penthouse Forum, and asking random people in a mall questions about their sexual history, penis size and how far they can ejaculate. Rushton’s penis data, and even one of the final papers he penned “Do pigmentation and the melanocortin system modulate aggression and sexuality in humans as they do in other animals?” (Rushton and Templer, 2012) is so full of flaws I can’t believe it got past review. I guess a physiologist was not on the review board when Rushton’s and Templer’s paper went up for review…

Rushton pushed the just-so story of cold winters (which was his main thing and his racial differences hypothesis hinged on it), along with his long-refuted human r/K selection theory (see Anderson, 1991; Graves, 2002). Also watch the debate between Rushton and Graves. Rushton got quite a lot wrong (see Flynn, 2019; Cernovsky and Litman, 2019), as a lot of people do, but he was in no way a “serious scholar”.

Why yes, Mr. Herrnstein and Mr. Murray, Rushton was, indeed, a very serious scholar who has amassed serious data.

The Malleability of IQ

1700 words

1843 Magazine published an article back in July titled The Curse of Genius, stating that “Within a few points either way, IQ is fixed throughout your life …” How true is this claim? How much is “a few points”? Would it account for any substantial increase or decrease? A few studies do look at IQ scores in one sample longitudinally. So, if this is the case, then IQ is not “like height”, as most hereditarians claim—it being “like height” since height is “stable” at adulthood (like IQ) and only certain events can decrease height (like IQ). But these claims fail.

IQ is, supposedly, a stable trait—that is, like height, at a certain age, it does not change. (Other than sufficient life events, such as having a bad back injury that causes one to slouch over, causing a decrease in height, or getting a traumatic brain injury—though that does not always decrease IQ scores). IQ tests supposedly measure a stable biological trait—“g” or general intelligence (which is built into the test, see Richardson, 2002 and see Schonemann’s papers for refutations on Jensen’s and Spearman’s “g“).

IQ levels are expected to stick to people like their blood group or their height. But imagine a measure of a real, stable bodily function of an individual that is different at different times. You’d probably think what a strange kind of measure. IQ is just such a measure. (Richardson, 2017: 102)

Neuroscientist Allyson Mackey’s team, for example, found “that after just eight weeks of playing these games the kids showed a pretty big IQ change – an improvement of about 30% or about 10 points in IQ.” Looking at a sample of 7-9 year olds, Mackey et al (2011) recruited children from low SES backgrounds to participate in cognitive training programs for an hour a day, 2 days a week. They predicted that children from a lower SES would benefit more from such cognitive/environmental enrichment (indeed, think of the differences between lower and middle SES people).

Mackey et al (2011) tested the children on their processing speed (PS), working memory (WM), and fluid reasoning (FR). Assessing FR, they used a matrix reasoning task with two versions (for the retest after the 8 week training). For PS, they used a cross-out test where “one must rapidly identify and put a line through each instance of a specific symbol in a row of similar symbols” (Mackey et al, 2011: 584). While the coding “is a timed test in which one must rapidly translate digits into symbols by identifying the corresponding symbol for a digit provided in a legend” (ibid.) which is a part of the WISC IV. Working memory was assessed through digit and spatial span tests from the Wechsler Memory Scale.

The kinds of games they used were computerized and non-computerized (like using a Nintendo DS). Mackey et al (2011: 585) write:

Both programs incorporated a mix of commercially available computerized and non-computerized games, as well as a mix of games that were played individually or in small groups. Games selected for reasoning training demanded the joint consideration of several task rules, relations, or steps required to solve a problem. Games selected for speed training involved rapid visual processing and rapid motor responding based on simple task rules.

So at the end of the 8-week program, cognitive abilities increased in both groups. For the children in the reasoning training, they solved an average of 4.5 more matrices than their previous try. Mackey et al (585-586) write:

Before training, children in the reasoning group had an average score of 96.3 points on the TONI, which is normed with a mean of 100 and a standard deviation of 15. After training, they had an average score of 106.2 points. This gain of 9.9 points brought the reasoning ability of the group from below average for their age. [But such gains were not significant on the test of nonverbal intelligence, showing an increase of 3.5 points.]

One of the biggest surprises was that 4 out of the 20 children in the reasoning training showed an increase of over 20 points. This, of course, refutes the claim that such “ability” is “fixed”, as hereditarians have claimed. Mackey et al (2011: 587) writes that “the very existence and widespread use of IQ tests rests on the assumption that tests of FR measure an individual’s innate capacity to learn.” This, quite obviously, is a false claim. (This claim comes from Cattell, no less.) This buttresses the claim that IQ tests are, of course, experience dependent.

This study shows that IQ is not malleable and that exposure to certain cultural tools leads to increases in test scores, as hypothesized (Richardson, 2002, 2017).

Salthouse (2013) writes that:

results from different types of approaches are converging on a conclusion that practice or retest contributions to change in several cognitive abilities appear to be nearly the same magnitude in healthy adults between about 20 and 80 years of age. These findings imply that age comparisons of longitudinal change are not confounded with differences in the influences of retest and maturational components of change, and that measures of longitudinal change may be underestimates of the maturational component of change at all ages.

Moreno et al (2011) show that after 20 days of computerized training, children in the music group showed enhanced scores on a measure of verbal ability—90 percent of the sample showed the same improvement. They further write that “the fact that only one of the groups showed a positive correlation between brain plasticity (P2) and verbal IQ changes suggests a link between the specific training and the verbal IQ outcome, rather than improvement due to repeated testing.”

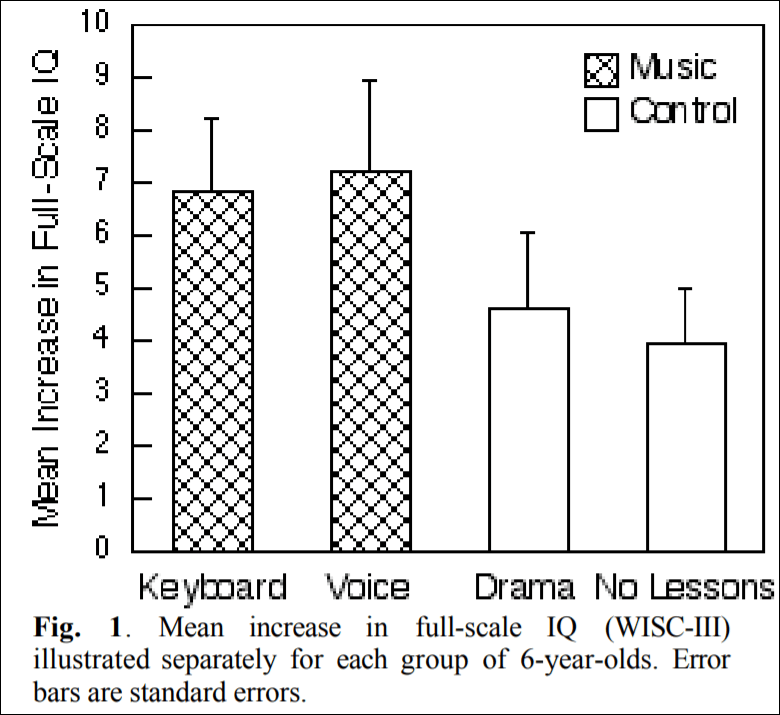

Schellenberg (2004) describes how there was an advertisement looking for 6 year olds to enroll them in art lessons. There were 112 children enrolled into four groups: two groups received music lessons for a year, on either a standard keyboard or they had Kodaly voice training while the other two groups received either drama training or no training at all. Schellenberg (2004: 3) writes that “Children in the control groups had average

increases in IQ of 4.3 points (SD = 7.3), whereas the music groups had increases of 7.0 points (SD = 8.6).” So, compared to either drama training or no training at all, the children in the music training gained 2.7 IQ points more.

(Figure 1 from Schellenberg, 2004)

Ramsden et al (2011: 3-4) write:

The wide range of abilities in our sample was confirmed as follows: FSIQ ranged from 77 to 135 at time 1 and from 87 to 143 at time 2, with averages of 112 and 113 at times 1 and 2, respectively, and a tight correlation across testing points (r 5 0.79; P , 0.001). Our interest was in the considerable variation observed between testing points at the individual level, which ranged from 220 to 123 for VIQ, 218 to 117 for PIQ and 218 to 121 for FSIQ. Even if the extreme values of the published 90% confidence intervals are used on both occasions, 39% of the sample showed a clear change in VIQ, 21% in PIQ and 33% in FSIQ. In terms of the overall distribution, 21% of our sample showed a shift of at least one population standard deviation (15) in the VIQ measure, and 18% in the PIQ measure. [Also see The Guardian article on this paper.[

Richardson (2017: 102) writes “Carol Sigelman and Elizabeth Rider reported the IQs of one group of children tested at regular intervals between the ages of two years and seventeen years. The average difference between a child’s highest and lowest scores was 28.5 points, with almost one-third showing changes of more than 30 points (mean IQ is 100). This is sufficient to move an individual from the bottom to the top 10 percent or vice versa.” [See also the page in Sigelman and Rider, 2011.]

Mortensen et al (2003) show that IQ remains stable in mid- to young adulthood in low birthweight samples. Schwartz et al (1975: 693) write that “Individual variations in patterns of IQ changes (including no changes over time) appeared to be related to overall level of adjustment and integration and, as such, represent a sensitive barometer of coping responses. Thus, it is difficult to accept the notion of IQ as a stable, constant characteristic of the individual that, once measured, determines cognitive functioning for any age level for any test.”

There is even instability in IQ seen in high SES Guatemalans born between 1941-1953 (Mansukoski et al, 2019). Mansukoski et al’s (2019) analysis “highlight[s] the complicated nature of measuring and interpreting IQ at different ages, and the many factors that can introduce variation in the results. Large variation in the pre-adult test scores seems to be more of a norm than a one-off event.” Possible reasons for the change could be due to “adverse life events, larger than expected deviations of individual developmental level at the time of the testing and differences between the testing instruments” (Mansukoski et al, 2019). They also found that “IQ scores did not significantly correlate with age, implying there is no straightforward developmental cause behind the findings“, how weird…

Summarizing such studies that show an increase in IQ scores in children and teenagers, Richardson (2017: 103) writes:

Such results suggest that we have no right to pin such individual differences on biology without the obvious, but impossible, experiment. That would entail swapping the circumstances of upper-and lower-class newborns—parents’ inherited wealth, personalities, stresses of poverty, social self-perception, and so on—and following them up, not just over years or decades, but also over generations (remembering the effects of maternal stress on children, mentioned above). And it would require unrigged tests based on proper cognitive theory.

In sum, the claim that IQ is stable at a certain age like another physical trait is clearly false. Numerous interventions and reasons can increase or decrease one’s IQ score. The results discussed in this article show that familiarity to certain types of cultural tools increases one’s score (like in the low SES group tested in Mackey et al, 2011). Although the n is low (which I know is one of the first things I will hear), I’m not worried about that. What I am worried about is the individual change in IQ at certain ages, and they show that. So the results here show support for Richardson’s (2002) thesis that “IQ scores might be more an index of individuals’ distance from the cultural tools making up the test than performance on a singular strength variable” (Richardson, 2012).

IQ is not stable; IQ is malleable, whether through exposure to certain cultural/class tools or through certain aspects that one is exposed to that are more likely to be included in certain classes over others. Indeed, this lends credence to Castles’ (2013) claim that “Intelligence is in fact a cultural construct, specific to a certain time and place.“

Why Did I Change My Views?

1050 words

I started this blog in June of 2015. I recall thinking of names for the blog, trying “politcallyincorrect.com” at first, but the domain was taken. I then decided on the name “notpoliticallycorrect.me”. Back then, of course, I was a hereditarian pushing the likes of Rushton, Kanazawa, Jensen, and others. I, to be honest, could never ever see myself disbelieving the “fact” that certain races were more or less intelligent than others, it was preposterous, I used to believe. IQ tests served as a completely scientific instrument which showed, however crudely, that certain races were more intelligent than others. I held these beliefs for around two years after the creation of this blog.

Back then, I used to go to Barnes n Noble and of course, go and browse the biology section, choose a book and drink coffee all day while reading. (I was drinking black coffee, of course.) I recall back in April of 2017 seeing this book DNA Is Not Destiny: The Remarkable, Completely Misunderstood Relationship between You and Your Genes on the shelf in the biology section. The baby blue cover of the book caught my eye—but I scoffed at the title. DNA most definitely was destiny, I thought. Without DNA we could not be who we were. I ended up buying the book and reading it. It took me about a week to finish it and by the end of the book, Heine had me questioning my beliefs.

In the book, Heine discusses IQ, heritability, genes, DNA testing to catch diseases, the MAOA gene, and so on. All in all, the book is against genetic essentialism which is rife in public—and even academic—thought.

After I read DNA Is Not Destiny, the next few weeks I went to Barnes n Noble I would keep seeing Ken Richardson’s Genes, Brains, and Human Potential: The Science and Ideology of Intelligence. I recall scoffing even more at the title than I did Heine’s book. Nevertheless, I did not buy the book but I kept seeing it every time I went. When I finally bought the book, my worldview was then transformed. Before, I thought of IQ tests as being able to—however crude—measure intelligence differences between individuals and groups. The number that spits out was one’s “intelligence quotient”, and there was no way to raise it—but of course there were many ways to decrease it.

But Richardson’s book showed me that there were many biases implicit in the study of “intelligence”, both conscious and unconscious. The book showed me the many false assumptions that IQ-ists make when constructing tests. Perhaps most importantly, it showed me that IQ test scores were due to one’s social class—and that social class encompasses many other variables that affect test performance, and so stating that IQ tests are instruments to identify one’s social class due to the construction of the test seemed apt—especially due to the content on the test along with the fact that the tests were created by members of a narrow upper-class. This, to me, ensured that the test designers would get the result they wanted.

Not only did this book change my views on IQ, but I did a complete 180 on evolution, too (which Fodor and Pitattelli-Palmarini then solidified). Richardson in chapters 4 and 5 shows that genes don’t work the way most popularly think they do and that they are only used by and for the physiological system to carry out different processes. I don’t know which part of this book—the part on IQ or evolution—most radically changed my beliefs. But after reading Richardson, I did discover Susan Oyama, Denis Noble, Eva Jablonka and Marion Lamb, David Moore, David Shenk, Paul Griffiths, Karola Stotz, Jerry Fodor. and others who opposed the Neo-Darwinian Modern Synthesis.

Richardson’s most recent book then lead me to his other work—and that of other critics of IQ and the current neo-Darwinian Modern Synthesis—and from then on, I was what most would term an “IQ-denier”—since I disbelieve the claim that IQ tests test intelligence, and an “evolution denier”—since I deny the claim that natural selection is a mechanism. In any case, the radical changes in both of my what I would term major views I held were slow-burning, occurring over the course of a few months.

This can be evidenced by just reading the archives of this blog. For example, check the archives from May 2017 and read my article Height and IQ Genes. One can then read the article from April 2017 titled Reading Wrongthought Books in Public to see that over a two-month period that my views slowly began to shift to “IQ-denalism” and that of the Extended Evolutionary Synthesis (EES). Of course, in June of 2017, after defending Rushton’s r/K selection theory for years, I recanted on those views, too, due to Anderson’s (1991) rebuttal of Rushton’s theory. That three-month period from April-June was extremely pivotal in shaping the current views I have today.

After reading those two books, my views about IQ shifted from that of one who believed that nothing could ever shake his belief in them to one of the most outspoken critics of IQ in the “HBD” community. But the views on evolution that I now hold may be more radical than my current views on IQ. This is because Darwin himself—and the theory he formulated—is the object of attack, not a test.

The views I used to hold were staunch; I really believed that I would never recant my views, because I was privy to “The Truth ™” and everyone else was just a useful idiot who did not believe in the reality of intelligence differences which IQ tests showed. Though, my curiosity got the best of me and I ended up buying two books that radically shifted my thoughts on IQ and along with that evolution itself.

So why did I change my views on IQ and evolution? I changed my views due to conceptual and methodological problems on both points that Richardson and Heine pointed out to me. These view changes I underwent more than two years ago were pretty shocking to me. As I realized that my views were beginning to shift, I couldn’t believe it, since I recall saying to myself “I’ll never change my views.” the inadequacy of the replies to the critics was yet another reason for the shift.

It’s funny how things work out.

Shockley and Cattell

2500 words

William Shockley and Raymond Cattell were some of the most prolific eugenicists of the 20th century. In that time, both men put forth the notion that breeding should be restricted based on the results of IQ testing. Both men, however, were motivated not by science—so much—as they were by racial biases. Historian Constance Hilliard discusses Shockley in her book Straightening the Bell Curve: How Stereotypes About Black Masculinity Drive Research on Race and Intelligence (Hilliard, 2012: Chapter 3), while psychologist William H. Tucker wrote a book on Cattell and the eugenic views he held called The Cattell Controversy: Race, Science, and Ideology (Tucker, 2009). This article will discuss the views of both men.

Shockley

When Shockley was 51 he was in a near-fatal car accident. He was thrown many feet away from the car that he, his wife and their son were in. Their son escaped the accident with minor injuries but Shockley had a crushed pelvis and was in a body cast for months in the hospital. Hilliard (2012: 20) writes:

Chapter 3 details Shockley’s transformation from physicist to modern-day eugenicist, preoccupied with race and the superiority of white genes. Some colleagues believed that the car accident that crushed Dr. Shockley’s pelvis and left him disabled might have triggered mental changes in him as well. Whatever the case, not long after returning home from the hospital, Shockley began directing his anger toward the reckless driver who maimed him into racial formulations. His ideas began to coalesce around the notion of an inverse correlation between blacks’ cognition and physical prowess. Later, in donating his sperm at the age of seventy to a sperm bank for geniuses, Shockley suggested to an interviewer for Playboy that women who would otherwise pay little attention to his lack of physical appeal would compete for his cognitively superior sperm. But the sperm banks’ owner apparently concealed from Shockley a painful truth. Women employing its services rejected the sperm of the short, balding Shockley in favor of that from younger, taller, more physically attractive men, whatever their IQ.

Shockley was a short, small man, standing at 5 foot 6 inches, weighing 150 pounds. How ironic that his belief that women would want his “cognitively superior sperm” (whatever that means) was rebuffed by the fact that women didn’t want a small, short balding man and wanted a young, attractive man’s sperm irrespective of their IQ. How funny, these eugenicists are.

Shockley’s views, of course, were not just science-driven. He harbored racial biases against certain groups. He disowned his son for marrying a Costa Rican woman, stated that his children had “regressed to the mean”, and stated that while stating that the so horrible misfortune of his children’s genetics were due to his first wife since she was not as academically inclined as he. Hilliard (2012: 48-49) writes:

Shockley’s growing preoccupation with eugenics and selective breeding was not simply an intellectual one. He disowned his eldest son for his involvement with a Costa Rican woman since this relationship, according to Professor Shockley, threatened to contaminate the family’s white gene pool. He also described his children to a reporter “as a significant regression” even though one possessed a PhD from the University of Southern California and another held a degree from Harvard College. Shockley even went as far as to blame this “genetic misfortune” on his first wife, who according to the scientist, “had no as high an academic achievement standing as I had.”

It’s funny because Shockley described himself as a “lady’s man”, but they didn’t want the sperm of a small, balding manlet (short man, at 5 foot 6 inches weighing 150 pounds). I wonder how he would have reacted to this news?

This is the mark of a scientist who just has intellectual curiosity on “cognitive differences” between racial groups, of course. Racial—and other—biases, of course, have driven many research programmes over the decades, and it seems that, like most “intelligence researchers” Shockley was privy to such biases as well.

One of Shockley’s former colleagues attributed his shift in research focus to the accident he had, stating that the “intense and (to my mind) ill-conceived concentration on socio-genetic matters occurred after a head-on automobile collison in which he was almost killed” (quoted in Hilliard: 2012: 48). Though we, of course, can’t know the reason for Shockley’s change in research focus (from legitimate science to pseudoscience), racial biases were quite obviously a driver in his research-shift.

Hilliard (2012: 47) claims that “had it not been for the near fatal car accident [that occurred to Shockley] … the twentieth century’s preoccupation with pairing cognition and physical attributes might have faded from view. It much not have been so much the car crash as the damage it did to Shockley’s sense of self that changed the course of race science.” Evidence for this claim comes from the fact that Jensen was drawn to Shockley’s lectures. Hilliard (2012: 51-52) writes:

Jensen, who had described himself as a “frustrated symphony conductor,” may have had his own reasons for reverencing Shockley’s every word. The younger psychologist had been forced to abandon a career in music because his own considerable talents in that area nevertheless lacked “soul,” or the emotional intensity needed to succeed in so competitive a profession. He decided on psychology as a second choice, carrying along with him a grudge against those American subcultures perceived as being “more expressive” than white culture from white he sprang.

So, it seems that had Shockley passed away, one of the “IQ giants” would have not have become an IQ-ist and Jensenism would not exist. Then, maybe, we would not have this IQ pseudoscience that America is “obsessed with” (Castles, 2013).

Cattell

Raymond B. Cattell is one of the most influential psychologists of the 20th century. Tucker (2009) shows how Cattell’s racial biases drove his research programs and how Cattell outlined his radical eugenic thoughts in numerous papers on personality and social psychology. Tucker describes Cattell’s acceptance of an award from the APA. However, the APA then got word of Cattell’s views and what drove his research a few days before Cattell was to fly to Hawaii to accept the award. It was said to the APA that Cattell harbored racist views which drove his research. Cattell even created a religion called “Beyondism” which is a “neo-fascist contrivance” (Mehler, 1997) in which eugenics was a part, but only on a voluntary basis.

Cattell titled a book on the matter A New Morality from Science: Beyondism (Cattell, 1972). It’s almost as if he’s saying that there can be a science of morality, but there cannot be one (contra Sam Harris). Cattell, in his book, thought of how to create a system in which ecologically sustainable eugenic programs could be established. He also published Beyondism: Religion from Science in 1987 (Cattell, 1987). Cattell’s eugenic beliefs were so strong that he actually created a “religion” based on it. It is indeed ironic, since many HBDers are religious in their views.

Tucker (2009: 14) was one of two psychologists to explain to the APA that “this was not a case of a scientist who, parenthetically, happened to have objectionable political opinions; Cattell’s political ideology and his science were inseparable from each other.” So the APA postponed the award ceremony for Cattell. Tucker (2009: 15) demonstrated “that [Cattell’s] impressive body of accomplishments in the former domain [his “scienctific” accomplishments] was always intended to serve the goal of the latter [his eugenic/political beliefs].”

Cattell’s religion was based on evolution. A believer in group selection, he claimed that racial groups were selected by “natural selection“, thusly being married to a form of group selection. Where Beyondism strayed from other religious movements is interesting and is the main point of Cattell’s new religion: compassion was seen by Cattell as “evil.” Tucker (2009: 136) writes:

Cattell finally published A New Morality From Science: Beyondism, a 480-page prolix tome describing his religious thought in detail; fifteen years later Beyondism: Religion from Science provided some elaboration of Beyondist principles. Together these two books constituted the most comprehensive statement of his sociomoral beliefs and their relation to social science. Despite the adjective in the title of the earlier volume, Beyondism showed no significant discontinuity from the “evolutionary ethics” of the 1930s. If anything, the intervening decades had made all the traditonal approaches to morality more contemptible than ever to Cattell. “The notion of ‘human rights'” was nothing more than “an instance of rigid, childish, subjective thinking,” and other humanistic principles “such … as ‘social justice and equality,’ ‘basic freedom’ and ‘human dignity,'” he dismissed as “whore phrases.” As always, conventional religion was the worst offender of all in his eyes, one of its “chief rasions detre [sic]” being the “succorance of failure of error” by prolonging the duration of genetic failures—both individuals and groups—which, “from the perspective Beyondism,” Cattell called “positively evil.” In contrast, in a religion based on evolution as the central purpose of humankind, “religious and scientific truth [would] be ultimately reducible to one truth … [obtained] by scientific discovery … therefore … developing morality out of science. Embodying this unified truth, Beyondism would be “the finest ways to spend our lives.”

So intergroup competition, to Cattell, was the mechanism for “evolutionary progress” (whatever that means; see my most recent essay on the matter). The within-group eugenic policies that Beyondism would put onto racial groups was not only for increasing the race’s quality of life, but to increase the chance of that race’s being judged “successful” in Cattell’s eyes.

Another main tenet of Beyondism is that one culture should not borrow from another, termed “cultural borrowing”. This separated “rewards” from their “genetic origins” which then “confused the process of natural selection between groups.” So Beyondism required the steady elimination of “failing” races which was essential if the earth was “not to be choked with … more primitive forerunners” (Cattell, quoted in Tucker, 2009: 146). Cattell did not use the term “genocide”, which he saved only for the literal killing off of the members of a group; he created a neologism called “genthanasia” which was the process of ““phasing out” a “moribund culture … by educational and birth measures, without a single member dying before his time” (Cattell, quoted in Tucker, 2009: 146). So, quite obviously, Beyondism could not be practiced by one individual; it needed groups—societies—to adhere to its tenets for it to be truly effective. To Cattell, the main draw of Beyondism was that intergroup competition was a necessary moral postulate while he used psychological data to parse out “winners” and “losers.”

Cattell was then put on the Editorial Advisory Board of Mankind Quarterly, which was formerly a journal populated by individuals who opposed civil rights and supported German National Socialism. Cattell, though, finally had a spot where he could publish his thoughts in a “journal” on what should be done in regard to his Beyondism religion. Tucker (2009: 153) writes:

… in an article titled “Virtue in ‘Racism’?” he offered an analysis similar to Pearson’s, arguing that racism was an innate “evolutionary force—a tendency to like the like and distrust the different” that in most cases had to be respected as ” a virtuous gift”; the mere fact that society “has had to battel racism” was for Cattell “sufficient evidence that an innate drive exists.” And rather than regarding such natural inclination as a “perversion,” the appropriate response to racism, in his opinion, was “to shape society to adjust to it,” no doubt keeping groups separate from each other.

One of Cattell’s colleagues—Oliver Robertson (a man who criticized Hitler for failing)—wrote a book in 1992 titled The Ethnostate: An Unblinkered Perspective for an Advanced Statecraft in which he detailed his plan for the balkanization (the division of one large region into many smaller, sometimes hostile, ones) which was Cattellian in nature. It seemed like The Ethnostate was just a whole bunch of Cattell’s ideas, packaged up into a “plan” for the balkanization of America. So he wanted to divide America into ethnostates. Recall how Cattell eschewed “cultural borrowing”; well so did Robertson. Tucker (2009: 166) writes:

Most important of all, in the competition between the different ethnostates each group was to rely solely “upon its own capabilities and resources,” prohibited from “borrowing” from more complex cultures advancements that “it could not create under its own power” or otherwise benefitting from outside assistance.

[…]

A critique of Cattell’s ethical system based in part on his involvement with others espousinig odious opinions naturally runs the risk of charging guilt by association. But the argument advanced here is more substantative. It is not merely that he has cited a long list of Far Right authors and activists as significant influences on his own work, including arguably the three most important English-speaking Nazi theorists of the last thirty years—Pearson, Oliver, and Robertson. It is that, in addition to citing their writing as support for his own ideology, Cattell has acknowledged their ideas as “integrable”—that is, compatible—with his thought; expressed his gratitude for their influence these ideas have had on the evolution of Beyondism; graced the pages of their journals with his own contributions, thus lending his considerable prestige to publications dedicated to keeping blacks in second-class status; registered no objection when schemes of racial balkanization were predicated expressly on his writing—and indeed edited a publication that praised such a scheme for its intellectual indebtedness to his thought and called for its implementaion; and provided a friendly interview to a periodical [American Rennaisance] directly advocating that constituonally protected rights be withheld from blacks. This is not guilt by association but rather guilt by collaboration: a core set of beliefs and a common vision of an ethnically cleansed future, and that his support for such a society has lent his academic prominence, consciosuly and deliberately, to their intolerable goals. (Tucker, 2009: 171)

Conclusion

The types of views these two men held, quite obviously, drove their “scientific aspirations”; and their racial biases permeated their scientific thought. Shockley’s sudden shift in his thought after his car accident is quite possibly how and why Jensen published his seminal article in 1969 which opened the race/”intelligence” debate back up. Shockley’s racial biases permeated into his familial life when his son married a Costa Rican woman; along with his thoughts on how his children “regressed to the mean” due to his first wife’s lack of educational attainment shows the kind of great guy that Shockley was. It also shows how his biases drove his thought.

The same with Cattell. Cattell’s religion Beyondism grew out of his extreme racial biases; his collaboration with National Socialists and those opposed to desegregation further shows how his political/racial beliefs drove his research. Beyondist propaganda stated that evolutionary “progress” occurred between competing groups. So this is when Robertson pretty much took all of Cattell’s ideas and wrote a book on how America will be balkanized into ethnostates where there would be no cultural borrowing. Further, he stated that the most appropriate response to racism was to shape society to adjust to racism, rather than attempt to eliminate it entirely.

The stories of these two men’s beliefs are why, in my opinion, we should know the past and motivations of why individuals push anything—no matter what type of field it is. Because biases—due to political beliefs—everywhere cloud people’s judgment. Although, holding such views was prevalent at the time (like with Henry Goddard and his Kallikak family (see Zenderland, 1998).

Five Years Away Is Always Five Years Away

1300 words

Five years away is always five years away. When one makes such a claim, they can always fall back on the “just wait five more years!” canard. Charles Murray is one who makes such claims. In an interview with the editor of Skeptic Magazine, Murray stated to Frank Miele:

I have confidence that in five years from now, and thereafter, this book will be seen as a major accomplishment.

This interview was in 1996 (after the release of the soft cover edition of The Bell Curve), and so “five years” would be 2001. But “predictions” such as this from HBDers (that the next big thing for their ideology, for example) is only X years away happens a lot. I’ve seen many HBDers make claims that only in 5 to 10 years the evidence for their position will come out. Such claims seem strangely religious to me. There is a reason for that. (See Conley and Domingue, 2016 for a molecular genetic refutation of The Bell Curve. While Murray’s prediction failed, 22 years after The Bell Curve’s publication, the claims of Murray and Herrnstein were refuted.)

Numerous people throughout history have made predictions regarding the date of Christ’s return. Some have used calculations to ascertain the date of Christ’s return, from the Bible. We can just take a look at the Wikipedia page for predictions and claims for the second coming of Christ where there are many (obviously failed) predictions of His return.

Take John Wesley’s claim that Revelations 12:14 referred to the day that Christ should come. Or one of Charles Taze Russell’s (the first president of the Watch Tower Society of Jehova’s Witnesses) claim that Jesus would return in 1874 and be ruling invisibly from heaven.

Russell’s beliefs began with Adventist teachings. While Russell, at first, did not take to the claim that Christ’s return could be predicted, that changed when he met Adventist author Nelson Barbour. The Adventists taught that the End Times began in 1799, Christ returned invisibly in 1874 with a physical return in 1878. (When this did not come to pass, many followers left Barbour and Russell states that Barbour did not get the event wrong, he just got the fate wrong.) So all Christians that died before 1874 would be resurrected, and Armageddon would begin in 1914. Since WWI began in 1914, Russell took that as evidence that his prediction was coming to pass. So Russell sold his clothing stores, worth millions of dollars today, and began writing and preaching about Christ’s imminent refuted. This doesn’t need to be said, but the predictions obviously failed.

So the date of 1914 for Armageddon (when Christ is supposed to return), was come to by Russell from studying the Bible and the great pyramids:

A key component to the calculation was derived from the book of Daniel, Chapter 4. The book refers to “seven times“. He interpreted each “time” as equal to 360 days, giving a total of 2,520 days. He further interpreted this as representing exactly 2,520 years, measured from the starting date of 607 BCE. This resulted in the year 1914-OCT being the target date for the Millennium.

Here is the prediction in Russell’s words “…we consider it an established truth that the final end of the kingdoms of this world, and the full establishment of the Kingdom of God, will be accomplished by the end of A.D. 1914” (1889). When 1914 came and went (sans the beginning of WWI which he took to be a sign of the, End Times), Russell changed his view.

Now, we can liken the Russell situation to Murray. Murray claimed that in 5 years after his book’s publication, that the “book would be seen as a major accomplishment.” Murray also made a similar claim back in 2016. Someone wrote to evolutionary biologist Joseph Graves about a talk Murray gave; he was offered an opportunity to debate Graves about his claims. Graves stated (my emphasis):

After his talk I offered him an opportunity to debate me on his claims at/in any venue of his choosing. He refused again, stating he would agree after another five years. The five years are in the hope of the appearance of better genomic studies to buttress his claims. In my talk I pointed out the utter weakness of the current genomic studies of intelligence and any attempt to associate racial differences in measured intelligence to genomic variants.

(Do note that this was back in April of 2016, about one year before I changed my hereditarian views to that of DST. I emailed Murray about this, he responded to me, and gave me permission to post his reply which you can read at the above link.)

Emil Kirkegaard stated on Twitter:

Do you wanna bet that future genomics studies will vindicate us? Ashkenazim intelligence is higher for mostly genetic reasons. Probably someone will publish mixed-ethnic GWAS for EA/IQ within a few years

Notice, though “within a few years” is vague; though I would take that to be, as Kirkegaard states next, three years. Kirkegaard was much more specific for PGS (polygenic scores) and Ashkenazi Jews, stating that “causal variant polygenic scores will show alignment with phenotypic gaps for IQ eg in 3 years time.” I’ll remember this; January 6th, 2022. (Though it was just an “example given”, this is a good example of a prediction from an HBDer.) Nevermind the problems with PGS/GWA studies (Richardson, 2017; Janssens and Joyner, 2019; Richardson and Jones, 2019).

I can see a prediction being made, it not coming to pass, and, just like Russel, one stating “No!! X, Y, and Z happened so that invalidated the prediction! The new one is X time away!” Being vague about timetables about as-of-yet-to-occur events it dishonest; stick to the claim, and if it does not occur….stop holding the view, just as Russel did. However, people like Murray won’t change their views; they’re too entrenched in this. Most may know that I over two years ago I changed my views on hereditarianism (which “is the doctrine or school of thought that heredity plays a significant role in determining human nature and character traits, such as intelligence and personality“) due to two books: DNA Is Not Destiny: The Remarkable, Completely Misunderstood Relationship between You and Your Genes and Genes, Brains, and Human Potential: The Science and Ideology of Intelligence. But I may just be a special case here.

Genes, Brains, and Human Potential then led me to the work of Jablonka and Lamb, Denis Noble, David Moore, Robert Lickliter, and others—the developmental systems theorists. DST is completely at-ends with the main “field” of “HBD”: behavioral genetics. See Griffiths and Tabery (2013) for why teasing apart genes and environment—nature and nurture—is problematic.

In any case, five years away is always five years away, especially with HBDers. That magic evidence is always “right around the corner”, despite the fact that none ever comes. I know that some HBDers will probably clamor that I’m wrong and that Murray or another “HBDer” has made a successful prediction and not immediately change the date of said prediction. But, just like Charles Taze Russell, when the prediction does not come to pass, just make something up about how and why the prediction didn’t come to pass and everything should be fine.

I think Charles Murray should change his name to Charles Taze Russel, since he pushed back the date of the prediction so many times. Though, to Russel’s credit, he did eventually recant on his views. I would find it hard to believe that Murray would; he’s too deep in this game and his career writing books and being an AEI pundit is on the line.

So I strongly doubt that Murray would ever come outright and say “I was wrong.” Too much money is on the line for him. (Note that Murray has a new book releasing in January titled Human Diversity: Gender, Race, Class, and Genes and you know that I will give a scathing review of it, since I already know Murray’s MO.) It’s ironic to me: Most HBDers are pretty religious in their convictions and can and will explain away data that doesn’t line up with their beliefs, just like a theist.

African Neolithic Part 1: Amending Common Misunderstandings

One of the weaknesses, in my opinion, to HBD is the focus on the Paleolithic and modern eras while glossing over the major developments in between. For instance, the links made between Paleolithic Western Europe’s Cromagnon Art and Modern Western Europe’s prowess (note the geographical/genetic discontinuity there for those actually informative on such matters).

Africa, having a worst archaeological record due to ideological histories and modern problems, leaves it rather vulnerable to reliance on outdated sources already discussed before on this blog. This lack of mention however isn’t strict.

Eventually updated material will be presented by a future outline of Neolithic to Middle Ages development in West Africa.

A recent example of an erroneous comparison would be in Heiner Rindermann’s Cogntivie Capitalism, pages 129-130. He makes multiple claims on precolonial African development to explained prolonged investment in magical thinking.

- Metallurgy not developed independently.

- No wheel.

- Dinka did not properly used cattle due to large, uneaten, portions left castrated.

- No domesticated animals of indigenous origin despite Europeans animals being just as dangerous, contra Diamond (lists African dogs, cats, antelope, gazelle, and Zebras as potential specimens, mentions European Foxes as an example of a “dangerous” animal to be recently domesticated along with African Antelopes in the Ukraine.

- A late, diffused, Neolithic Revolution 7000 years following that of the Middle East.

- Less complex Middle Age Structure.

- Less complex Cave structures.

Now, technically, much of this falls outside of what would be considered “neolithic”, even in the case of Africa. However, understanding the context of Neolithic development in Africa provides context to each of these points and periods of time by virtue of causality. Thus, they will be responded by archaeological sequence.

Dog domestication, Foxes, and human interaction.

The domestication of dogs occurred when Eurasian Hunter-Gathers intensified megafauna hunting, attracting less aggressive wild dogs to tame around 23k-25k ago. Rindermann’s mention of the fox experiment replicates this idea. Domestication isn’t a matter of breaking the most difficult of animals, it’s using the easiest ones to your advantage.

In this same scope, this needs to be compared to Africa’s case. In regards to behavior they are rarely solitary, so attracting lone individuals is already impractical. The species likewise developed under a different level of competition.

They were probably under as much competition from these predators as the ancestral African wild dogs were under from the guild of super predators on their continent.

What was different, though, is the ancestral wolves never evolved in an enviroment which scavenging from various human species was a constant threat, so they could develop behaviors towards humans that were not always characterized by extreme caution and fear.

Europe in particular shows that carnivore density was lower, and thus advantageous to hominids.

Consequently, the first Homo populations that arrived in Europe at the end of the late Early Pleistocene found mammal communities consisting of a low number of prey species, which accounted for a moderate herbivore biomass, as well as a diverse but not very abundant carnivore guild. This relatively low carnivoran density implies that the hominin-carnivore encounter rate was lower in the European ecosystems than in the coeval East African environments, suggesting that an opportunistic omnivorous hominin would have benefited from a reduced interference from the carnivore guild.

This would be a pattern based off of megafaunal extinction data.

The first hints of abnormal rates of megafaunal loss appear earlier, in the Early Pleistocene in Africa around 1 Mya, where there was a pronounced reduction in African proboscidean diversity (11) and the loss of several carnivore lineages, including sabertooth cats (34), which continued to flourish on other continents. Their extirpation in Africa is likely related to Homo erectus evolution into the carnivore niche space (34, 35), with increased use of fire and an increased component of meat in human diets, possibly associated with the metabolic demands of expanding brain size (36). Although remarkable, these early megafauna extinctions were moderate in strength and speed relative to later extinctions experienced on all other continents and islands, probably because of a longer history in Africa and southern Eurasia of gradual hominid coevolution with other animals.

This fundamental difference in adaptation to human presence and subsequent response is obviously a major detail in in-situ animal domestication.

Another example would be the failure of even colonialists to tame the Zebra.

Of course, this alone may not be good enough. One can nonetheless cite the tame-able Belgian Congo forest Elephant, or Eland. Therefore we can just ignore regurgitating Diamond.

This will just lead me to my next point. That is, what’s the pay-off?

Pastoralism and Utility

A decent test to understand what fauna in Africa can be utilized would the “experiments” of Ancient Egyptians, who are seen as the Eurasian “exception” to African civilization. Hyenas, and antelope from what I’ve, were kept under custody but overtime didn’t resulted in selected traits. The only domesticated animal in this region would be Donkeys, closer relatives to Zebras.