JP Rushton: Serious Scholar

1300 words

… Rushton is a serious scholar who has amassed serious data. (Herrnstein and Murray, 1996: 564)

How serious of a scholar is Rushton and what kind of “serious data” did he amass? Of course, since The Bell Curve is a book on IQ, H&M mean that his IQ data is “serious data” (I am not aware of Murray’s views on Rushton’s penis “data”). Many people over the course of Rushton’s career have pointed out that Rushton was anything but a “serious scholar who has amassed serious data.” Take, for example, Constance Hilliard’s (2012: 69) comments on Rushton’s escapades at a Toronto shopping mall where he trolled the mall looking for blacks, whites, and Asians (he payed them 5 dollars a piece) to ask them questions about their penis size, sexual frequency, and how far they can ejaculate:

An estimated one million customers pass through the doors of Toronto’s premier shopping mall, Eaton Centre, in any given week. Professor Jean-Phillipe Rushton sought out subjects in its bustling corridors for what was surely one of the oddest scientific studies that city had known yet—one that asked about males’ penis sizes. In Rushton’s mind, at least, the inverse correlation among races between intelligence and penis size was irrefutable. In fact, it was Rushton who made the now famous assertion in a 1994 interview with Rolling Stone magazine: “It’s a trade-off: more brains or more penis. You can’t have everything. … Using a grant from the conservative Pioneer Fund, the Canadian professor paid 150 customers at the Eaton Centre mall—one-third of whom he identified as black, another third white, and the final third Asian—to complete an elaborate survey. It included such questions such as how far the subject could ejaculate and “how large [is] your penis?” Rushton’s university, upon learning of this admittedly unorthodox research project, reprimanded him for not having the project preapproved. The professor defended his study by insisting that approval for off-campus experiments had never been required before. “A zoologist,” he quipped, “doesn’t need permission to study squirrels in his back yard.” [As if one does not need to get approval from the IRB before undertaking studies on humans… nah, this is just an example of censorship from the Left who want to hide the truth of ‘innate’ racial differences!]

(I wonder if Rushton’s implicit assumption here was that, since the brain takes most of a large amount of our consumed energy to power, that since blacks had smaller brains and larger penises that the kcal consumed was going to “power” their larger penis? The world may never know.)

Imagine you’re walking through a mall with your wife and two children. As your shopping, you see a strange man with a combover, holding measuring tape, approaching different people (which you observe are the three different social-racial groups) asking them questions for a survey. He then comes up to you and your family, pulling you aside to ask you questions about the frequency of the sex you have, how far you can ejaculate and how long your penis is.

Rushton: “Excuse me sir. My name is Jean-Phillipe Rushton and I am a psychologist at the University of Western Ontario. I am conducting a research study, surveying individuals in this shopping mall, on racial differences in penis size, sexual frequency, and how far they can ejaculate.”

You: “Errrrr… OK?”, you say, looking over uncomfortably at your family, standing twenty feet away.

Rushton: “First off, sir, I would like to ask you which race you identify as.”

You: “Well, professor, I identify as black, quote obviously“, as you look over at your wife who has a stern look on her face.

Rushton: “Well, sir, my first question for you is: How far can you ejaculate?”

You: “Ummm I don’t know, I’ve never thought to check. What kind of an odd question is that?“, you say, as you try to keep your voice down as to not alert your wife and children to what is being discussed.

Rushton: “OK, sir. How long would you say your penis is?”

You: “Professor, I have never measured it but I would say it is about 7 inches“, you say, with an uncomfortable look on your face. You think “Why is this strange man asking me such uncomfortable questions?

Rushton: “OK, OK. So how much sex would you say you have with your wife? And what size hat do you wear?“, asked Rushton, it seeming like he’s sizing up your whole body, with a twinkle in his eye.

You: “I don’t see how that’s any of your business, professor. What I do with my wife in the confines of my own home doesn’t matter to you. What does my hat size have to do with anything?”, you say, not knowing Rushton’s ulterior motives for his “study.” “I’m sorry, but I’m going to have to cut this interview short. My wife is getting pissed.”

Rushton: “Sir, wait!! Just a few more questions!”, Rushton says while chasing you with the measuring tape dragging across the ground, while you get away from him as quickly as possible, alerting security to this strange man bothering—harasasing—mall shoppers.

If I was out shopping and some strange man started asking me such questions, I’d tell him tough luck bro, find someone else. (I don’t talk to strange people trying to sell me something or trying to get information out of me.) In any case, what a great methodology, Rushton, because men lie about their penis size when asked.

Hilliard (2012: 71-72) then explains how Rushton used the “work” of the French Army Surgeon (alias Dr. Jacobus X):

Writing under the pseudonym Dr. Jacobus X, the author asserted that it was a personal diary that brought together thirty years of medical practice as a French government army surgeon and physician. Rushton was apparently unaware that the book while unknown to American psychologists, was familiar to anthropologists working in Africa and Asia and that they had nicknamed the genre from which it sprang “anthroporn.” Such books were not actually based on scientific research at all; rather, they were a uniquely Victorian style of pornography, thinly disguised as serious medical field research. Untrodden Fields [the title of Dr. Jacobus X’s book that Rushton drew from] presented Jacobus X’s observations and photographs of the presumably lurid sexual practices of exotic peoples, including photographs of the males’ mammoth-size sexual organs.

[…]

In the next fifteen years, Rushton would pen dozens of articles in academic journals propounding his theories of an inverse correlation among the races between brain and genital size. Much of the data he used to “prove” the enormity of the black male organ, which he then correlated inversely to IQ, came from Untrodden Fields. [Also see the discussion of “French Army Surgeon” in Weizmann et al, 1990: 8. See also my articles on penis size on this blog.]

Rushton also cited “research” from the Penthouse forum (see Rushton, 1997: 169). Citing an anonymous “field surgeon”, the Penthouse Forum, and asking random people in a mall questions about their sexual history, penis size and how far they can ejaculate. Rushton’s penis data, and even one of the final papers he penned “Do pigmentation and the melanocortin system modulate aggression and sexuality in humans as they do in other animals?” (Rushton and Templer, 2012) is so full of flaws I can’t believe it got past review. I guess a physiologist was not on the review board when Rushton’s and Templer’s paper went up for review…

Rushton pushed the just-so story of cold winters (which was his main thing and his racial differences hypothesis hinged on it), along with his long-refuted human r/K selection theory (see Anderson, 1991; Graves, 2002). Also watch the debate between Rushton and Graves. Rushton got quite a lot wrong (see Flynn, 2019; Cernovsky and Litman, 2019), as a lot of people do, but he was in no way a “serious scholar”.

Why yes, Mr. Herrnstein and Mr. Murray, Rushton was, indeed, a very serious scholar who has amassed serious data.

The Malleability of IQ

1700 words

1843 Magazine published an article back in July titled The Curse of Genius, stating that “Within a few points either way, IQ is fixed throughout your life …” How true is this claim? How much is “a few points”? Would it account for any substantial increase or decrease? A few studies do look at IQ scores in one sample longitudinally. So, if this is the case, then IQ is not “like height”, as most hereditarians claim—it being “like height” since height is “stable” at adulthood (like IQ) and only certain events can decrease height (like IQ). But these claims fail.

IQ is, supposedly, a stable trait—that is, like height, at a certain age, it does not change. (Other than sufficient life events, such as having a bad back injury that causes one to slouch over, causing a decrease in height, or getting a traumatic brain injury—though that does not always decrease IQ scores). IQ tests supposedly measure a stable biological trait—“g” or general intelligence (which is built into the test, see Richardson, 2002 and see Schonemann’s papers for refutations on Jensen’s and Spearman’s “g“).

IQ levels are expected to stick to people like their blood group or their height. But imagine a measure of a real, stable bodily function of an individual that is different at different times. You’d probably think what a strange kind of measure. IQ is just such a measure. (Richardson, 2017: 102)

Neuroscientist Allyson Mackey’s team, for example, found “that after just eight weeks of playing these games the kids showed a pretty big IQ change – an improvement of about 30% or about 10 points in IQ.” Looking at a sample of 7-9 year olds, Mackey et al (2011) recruited children from low SES backgrounds to participate in cognitive training programs for an hour a day, 2 days a week. They predicted that children from a lower SES would benefit more from such cognitive/environmental enrichment (indeed, think of the differences between lower and middle SES people).

Mackey et al (2011) tested the children on their processing speed (PS), working memory (WM), and fluid reasoning (FR). Assessing FR, they used a matrix reasoning task with two versions (for the retest after the 8 week training). For PS, they used a cross-out test where “one must rapidly identify and put a line through each instance of a specific symbol in a row of similar symbols” (Mackey et al, 2011: 584). While the coding “is a timed test in which one must rapidly translate digits into symbols by identifying the corresponding symbol for a digit provided in a legend” (ibid.) which is a part of the WISC IV. Working memory was assessed through digit and spatial span tests from the Wechsler Memory Scale.

The kinds of games they used were computerized and non-computerized (like using a Nintendo DS). Mackey et al (2011: 585) write:

Both programs incorporated a mix of commercially available computerized and non-computerized games, as well as a mix of games that were played individually or in small groups. Games selected for reasoning training demanded the joint consideration of several task rules, relations, or steps required to solve a problem. Games selected for speed training involved rapid visual processing and rapid motor responding based on simple task rules.

So at the end of the 8-week program, cognitive abilities increased in both groups. For the children in the reasoning training, they solved an average of 4.5 more matrices than their previous try. Mackey et al (585-586) write:

Before training, children in the reasoning group had an average score of 96.3 points on the TONI, which is normed with a mean of 100 and a standard deviation of 15. After training, they had an average score of 106.2 points. This gain of 9.9 points brought the reasoning ability of the group from below average for their age. [But such gains were not significant on the test of nonverbal intelligence, showing an increase of 3.5 points.]

One of the biggest surprises was that 4 out of the 20 children in the reasoning training showed an increase of over 20 points. This, of course, refutes the claim that such “ability” is “fixed”, as hereditarians have claimed. Mackey et al (2011: 587) writes that “the very existence and widespread use of IQ tests rests on the assumption that tests of FR measure an individual’s innate capacity to learn.” This, quite obviously, is a false claim. (This claim comes from Cattell, no less.) This buttresses the claim that IQ tests are, of course, experience dependent.

This study shows that IQ is not malleable and that exposure to certain cultural tools leads to increases in test scores, as hypothesized (Richardson, 2002, 2017).

Salthouse (2013) writes that:

results from different types of approaches are converging on a conclusion that practice or retest contributions to change in several cognitive abilities appear to be nearly the same magnitude in healthy adults between about 20 and 80 years of age. These findings imply that age comparisons of longitudinal change are not confounded with differences in the influences of retest and maturational components of change, and that measures of longitudinal change may be underestimates of the maturational component of change at all ages.

Moreno et al (2011) show that after 20 days of computerized training, children in the music group showed enhanced scores on a measure of verbal ability—90 percent of the sample showed the same improvement. They further write that “the fact that only one of the groups showed a positive correlation between brain plasticity (P2) and verbal IQ changes suggests a link between the specific training and the verbal IQ outcome, rather than improvement due to repeated testing.”

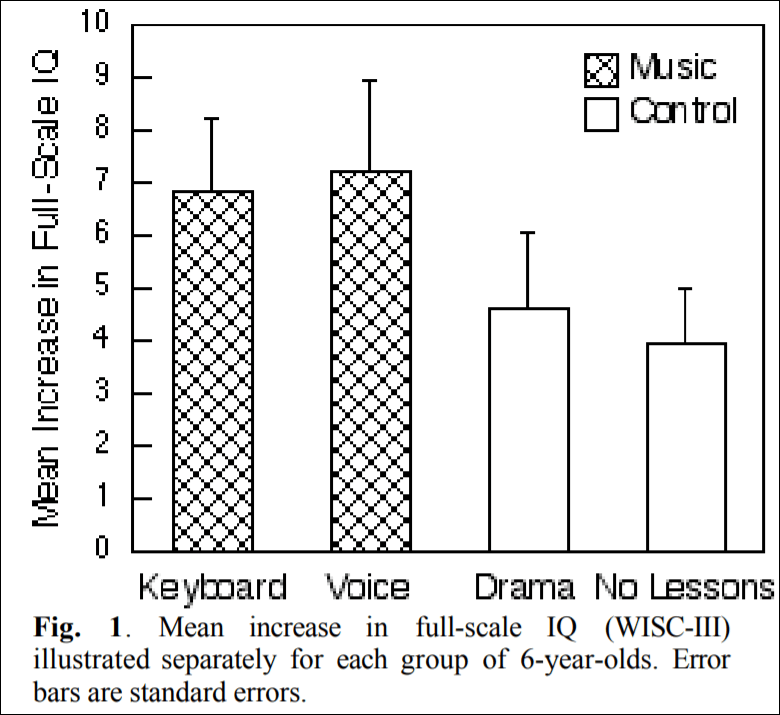

Schellenberg (2004) describes how there was an advertisement looking for 6 year olds to enroll them in art lessons. There were 112 children enrolled into four groups: two groups received music lessons for a year, on either a standard keyboard or they had Kodaly voice training while the other two groups received either drama training or no training at all. Schellenberg (2004: 3) writes that “Children in the control groups had average

increases in IQ of 4.3 points (SD = 7.3), whereas the music groups had increases of 7.0 points (SD = 8.6).” So, compared to either drama training or no training at all, the children in the music training gained 2.7 IQ points more.

(Figure 1 from Schellenberg, 2004)

Ramsden et al (2011: 3-4) write:

The wide range of abilities in our sample was confirmed as follows: FSIQ ranged from 77 to 135 at time 1 and from 87 to 143 at time 2, with averages of 112 and 113 at times 1 and 2, respectively, and a tight correlation across testing points (r 5 0.79; P , 0.001). Our interest was in the considerable variation observed between testing points at the individual level, which ranged from 220 to 123 for VIQ, 218 to 117 for PIQ and 218 to 121 for FSIQ. Even if the extreme values of the published 90% confidence intervals are used on both occasions, 39% of the sample showed a clear change in VIQ, 21% in PIQ and 33% in FSIQ. In terms of the overall distribution, 21% of our sample showed a shift of at least one population standard deviation (15) in the VIQ measure, and 18% in the PIQ measure. [Also see The Guardian article on this paper.[

Richardson (2017: 102) writes “Carol Sigelman and Elizabeth Rider reported the IQs of one group of children tested at regular intervals between the ages of two years and seventeen years. The average difference between a child’s highest and lowest scores was 28.5 points, with almost one-third showing changes of more than 30 points (mean IQ is 100). This is sufficient to move an individual from the bottom to the top 10 percent or vice versa.” [See also the page in Sigelman and Rider, 2011.]

Mortensen et al (2003) show that IQ remains stable in mid- to young adulthood in low birthweight samples. Schwartz et al (1975: 693) write that “Individual variations in patterns of IQ changes (including no changes over time) appeared to be related to overall level of adjustment and integration and, as such, represent a sensitive barometer of coping responses. Thus, it is difficult to accept the notion of IQ as a stable, constant characteristic of the individual that, once measured, determines cognitive functioning for any age level for any test.”

There is even instability in IQ seen in high SES Guatemalans born between 1941-1953 (Mansukoski et al, 2019). Mansukoski et al’s (2019) analysis “highlight[s] the complicated nature of measuring and interpreting IQ at different ages, and the many factors that can introduce variation in the results. Large variation in the pre-adult test scores seems to be more of a norm than a one-off event.” Possible reasons for the change could be due to “adverse life events, larger than expected deviations of individual developmental level at the time of the testing and differences between the testing instruments” (Mansukoski et al, 2019). They also found that “IQ scores did not significantly correlate with age, implying there is no straightforward developmental cause behind the findings“, how weird…

Summarizing such studies that show an increase in IQ scores in children and teenagers, Richardson (2017: 103) writes:

Such results suggest that we have no right to pin such individual differences on biology without the obvious, but impossible, experiment. That would entail swapping the circumstances of upper-and lower-class newborns—parents’ inherited wealth, personalities, stresses of poverty, social self-perception, and so on—and following them up, not just over years or decades, but also over generations (remembering the effects of maternal stress on children, mentioned above). And it would require unrigged tests based on proper cognitive theory.

In sum, the claim that IQ is stable at a certain age like another physical trait is clearly false. Numerous interventions and reasons can increase or decrease one’s IQ score. The results discussed in this article show that familiarity to certain types of cultural tools increases one’s score (like in the low SES group tested in Mackey et al, 2011). Although the n is low (which I know is one of the first things I will hear), I’m not worried about that. What I am worried about is the individual change in IQ at certain ages, and they show that. So the results here show support for Richardson’s (2002) thesis that “IQ scores might be more an index of individuals’ distance from the cultural tools making up the test than performance on a singular strength variable” (Richardson, 2012).

IQ is not stable; IQ is malleable, whether through exposure to certain cultural/class tools or through certain aspects that one is exposed to that are more likely to be included in certain classes over others. Indeed, this lends credence to Castles’ (2013) claim that “Intelligence is in fact a cultural construct, specific to a certain time and place.“

Chopsticks Genes and Population Stratification

1200 words

Why do some groups of people use chopsticks and others do not? Years back, created a thought experiment. So he found a few hundred students from a university and gathered DNA samples from their cheeks which were then mapped for candidate genes associated with chopstick use. Come to find out, one of the associated genetic markers was associated with chopstick use—accounting for 50 percent of the variation in the trait (Hamer and Sirota, 2000). The effect even replicated many times and was highly significant: but it was biologically meaningless.

One may look at East Asians and say “Why do they use chopsticks” or “Why are they so good at using them while Americans aren’t?” and come to such ridiculous studies such as the one described above. They may even find an association between the trait/behavior and a genetic marker. They may even find that it replicates and is a significant hit. But, it can all be for naught, since population stratification reared its head. Population stratification “refers to differences in allele frequencies between cases and controls due to systematic differences in ancestry rather than association of genes with disease” (Freedman et al, 2004). It “is a potential cause of false associations in genetic association studies” (Oetjens et al, 2016).

Such population stratification in the chopsticks gene study described above should have been anticipated since they studied two different populations. Kaplan (2000: 67-68) described this well:

A similar argument, bu the way, holds true for molecular studies. Basically, it is easy to mistake mere statistical associations for a causal connection if one is not careful to properly partition one’s samples. Hamer and Copeland develop and amusing example of some hypothetical, badly misguided researchers searching for the “successful use of selected hand instruments” (SUSHI) gene (hypothesized to be associated with chopstick usage) between residents in Tokyo and Indianapolis. Hamer and Copeland note that while you would be almost certain to find a gene “associated with chopstick usage” if you did this, the design of such a hypothetical study would be badly flawed. What would be likely to happen here is that a genetic marker associated with the heterogeneity of the group involved (Japanese versus Caucasian) would be found, and the heterogeneity of the group involved would independently account for the differences in the trait; in this case, there is a cultural tendency for more people who grow up in Japan than people who grow up in Indianapolis to learn how to use chopsticks. That is, growing up in Japan is the causally important factor in using chopsticks; having a certain genetic marker is only associated with chopstick use in a statistical way, and only because those people who grow up in Japan are also more likely to have the marker than those who grew up in Indianapolis. The genetic marker is in no way causally related to chopstick use! That the marker ends up associated with chopstick use is therefore just an accident of design (Hamer and Copeland, 1998, 43; Bailey 1997 develops a similar example).

In this way, most—if not all—of the results of genome-wide association studies (GWASs) can be accounted for by population stratification. Hamer and Sirota (2000) is a warning to psychiatric geneticists to not be quick to ascribe function and causation to hits on certain genes from association studies (of which GWASs are).

Many studies, for example, Sniekers et al (2017), Savage et al (2018) purport to “account for” less than 10 percent of the variance in a trait, like “intelligence” (derived from non-construct valid IQ tests). Other GWA studies purport to show genes that affect testosterone production and that those who have a certain variant are more likely to have low testosterone (Ohlsson et al, 2011). Population stratification can have an effect here in these studies, too. GWASs; they give rise to spurious correlations that arise due to population structure—which is what GWASs are actually measuring, they are measuring social class, and not a “trait” (Richardson, 2017b; Richardson and Jones, 2019). Note that correcting for socioeconomic status (SES) fails, as the two are distinct (Richardson, 2002). (Note that GWASs lead to PGSs, which are, of course, flawed too.)

Such papers presume that correlations are causes and that interactions between genes and environment either don’t exist or are irrelevant (see Gottfredson, 2009 and my reply). Both of these claims are false. Correlations can, of course, lead to figuring out causes, but, like with the chopstick example above, attributing causation to things that are even “replicable” and “strongly significant” will still lead to false positives due to that same population stratification. Of course, GWAS and similar studies are attempting to account for the heriatbility estimates gleaned from twin, family, and adoption studies. Though, the assumptions used in these kinds of studies are shown to be false and, therefore, heritability estimates are highly exaggerated (and flawed) which lead to “looking for genes” that aren’t there (Charney, 2012; Joseph et al, 2016; Richardson, 2017a).

Richardson’s (2017b) argument is simple: (1) there is genetic stratification in human populations which will correlate with social class; (2) since there is genetic stratification in human populations which will correlate with social class, the genetic stratification will be associated with the “cognitive” variation; (3) if (1) and (2) then what GWA studies are finding are not “genetic differences” between groups in terms of “intelligence” (as shown by “IQ tests”), but population stratification between social classes. Population stratification still persists even in “homogeneous” populations (see references in Richardson and Jones, 2019), and so, the “corrections for” population stratification are anything but.

So what accounts for the small pittance of “variance explained” in GWASs and other similar association studies (Sniekers et al, 2017 “explained” less than 5 percent of variance in IQ)? Population stratification—specifically it is capturing genetic differences that occurred through migration. GWA studies use huge samples in order to find the genetic signals of the genes of small effect that underline the complex trait that is being studied. Take what Noble (2018) says:

As with the results of GWAS (genome-wide association studies) generally, the associations at the genome sequence level are remarkably weak and, with the exception of certain rare genetic diseases, may even be meaningless (13, 21). The reason is that if you gather a sufficiently large data set, it is a mathematical necessity that you will find correlations, even if the data set was generated randomly so that the correlations must be spurious. The bigger the data set, the more spurious correlations will be found (3).

Calude and Longo (2016; emphasis theirs) “prove that very large databases have to contain arbitrary correlations. These correlations appear only due to the size, not the nature, of data. They can be found in “randomly” generated, large enough databases, which — as we will prove — implies that most correlations are spurious.”

So why should we take association studies seriously when they fall prey to the problem of population stratification (measuring differences between social classes and other populations) along with the fact that big datasets lead to spurious correlations? I fail to think of a good reason why we should take these studies seriously. The chopsticks gene example perfectly illustrates the current problems we have with GWASs for complex traits: we are just seeing what is due to social—and other—stratification between populations and not any “genetic” differences in the trait that is being looked at.

The Modern Synthesis vs the Extended Evolutionary Synthesis

2050 words

The Modern Synthesis (MS) has entrenched evolutionary thought since its inception in the mid-1950s. The MS is the integreation of Darwinian natural selection and Mendelian genetics. Key assumptions include “(i) evolutionarily significant phenotypic variation arises from genetic mutations that occur at a low rate independently of the strength and direction of natural selection; (ii) most favourable mutations have small phenotypic effects, which results in gradual phenotypic change; (iii) inheritance is genetic; (iv) natural selection is the sole explanation for adaptation; and (v) macro-evolution is the result of accumulation of differences that arise through micro-evolutionary processes” (Laland et al, 2015).

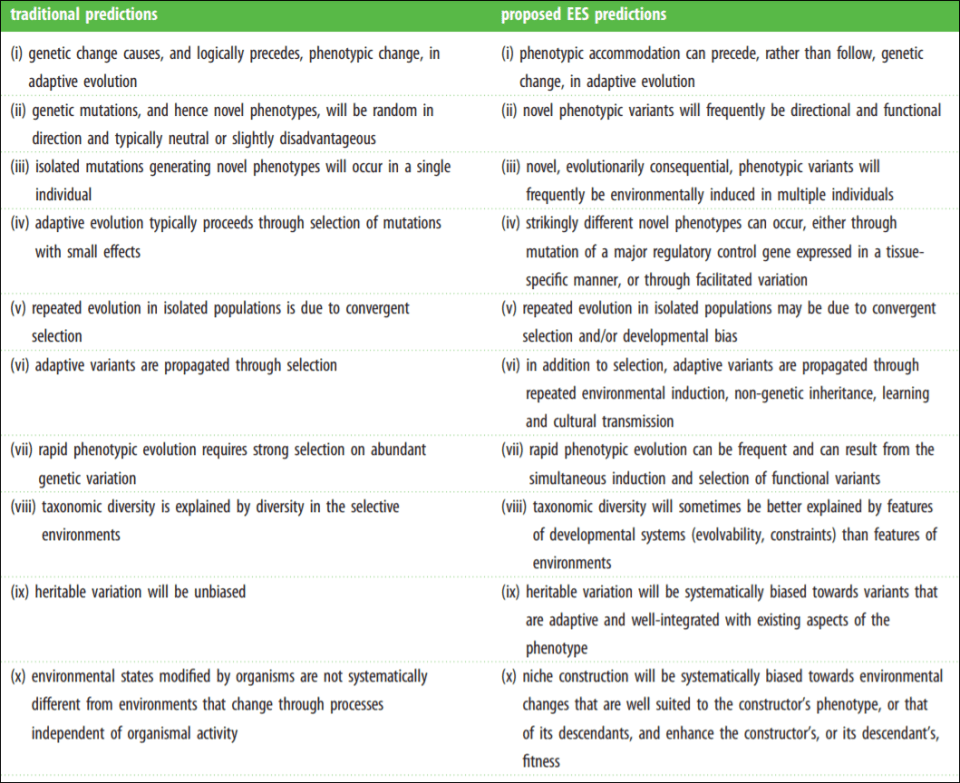

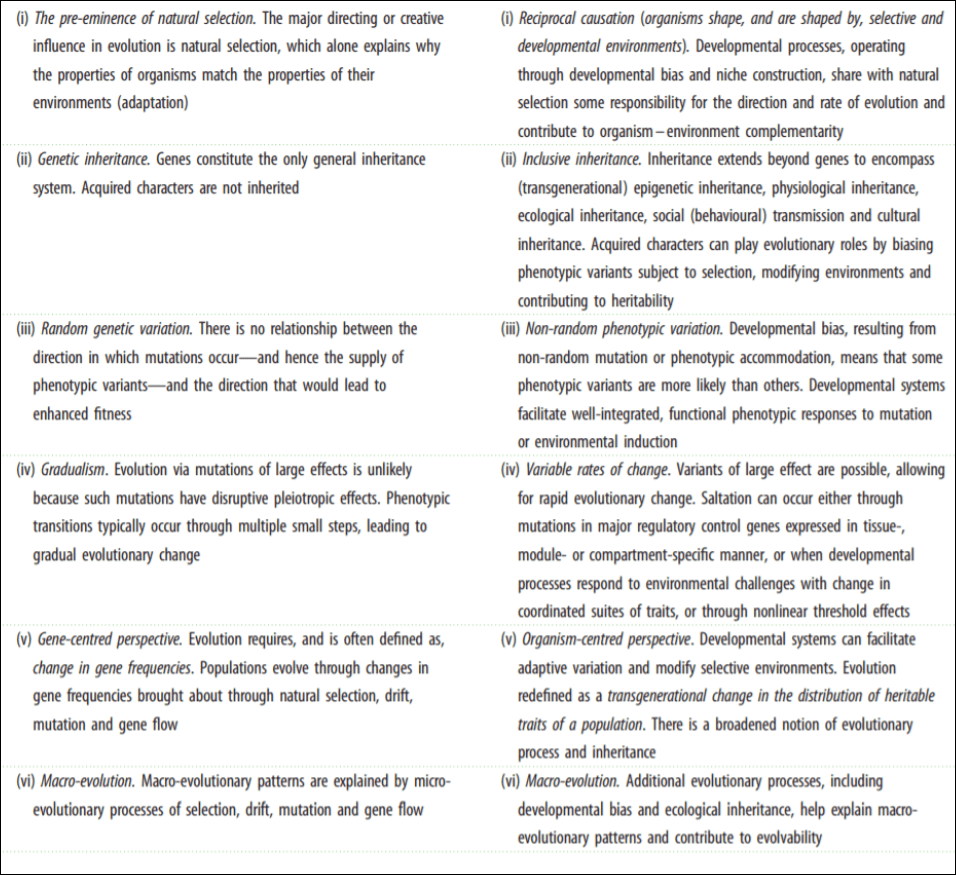

Laland et al (2015) even have a helpful table on core assumptions of both the MS and Extended Evolutionary Synthesis (EES). The MS assumptions are on the left while the EES assumptions are on the right.

Darwinian cheerleaders, such as Jerry Coyne and Richard Dawkins, would claim that neo-Darwinisim can—and already does—account for the assumptions of the EES. However, it is clear that that claim is false. At its core, the MS is a gene-centered perspective whereas the EES is an organism-centered perspective.

To the followers of the MS, evolution occurs through random mutations and change in allele frequencies which then get selected for by natural selection since they lead to an increase in fitness in that organism, and so, that trait that the genes ’cause’ then carry on to the next generation due to its contribution to fitness in that organism. Drift, mutation and gene flow also account for changes in genetic frequencies, but selection is the strongest of these modes of evolution to the Darwinian. The debate about the MS and the EES comes down to gene-selectionism vs developmental systems theory.

On the other hand, the EES is an organism-centered perspective. Adherents to the EES state that the organism is inseparable from its environment. Jarvilehto (1998) describes this well:

The theory of the organism-environment system (Jairvilehto, 1994, 1995) starts with the proposition that in any functional sense organism and environment are inseparable and form only one unitary system. The organism cannot exist without the environment and the environment has descriptive properties only if it is connected to the organism.

At its core, the EES makes evolution about the organism—its developmental system—and relegates genes, not as active causes of traits and behaviors, but as passive causes, being used by and for the system as needed (Noble, 2011; Richardson, 2017).

One can see that the core assumptions of the MS are very much like what Dawkins describes in his book The Selfish Gene (Dawkins, 1976). In the book, Dawkins claimed that we are what amounts to “gene machines”—that is, just vehicles for the riders, the genes. So, for example, since we are just gene machines, and if genes are literally selfish “things”, then all of our actions and behaviors can be reduced to the fact that our genes “want” to survive. But the “selfish gene” theory “is not even capable of direct empirical falsification” (Noble, 2011) because Richard Dawkins emphatically stated in The Extended Phenotype (Dawkins, 1982: 1) that “I doubt that there is any experiment that could prove my claim” (quoted in Noble, 2011).

Noble (2011) goes on to discuss Dawkins’ view that on genes:

Now they swarm in huge colonies, safe inside gigantic lumbering robots, sealed off from the outside world, communicating with it by tortuous indirect routes, manipulating it by remote control. They are in you and me; they created us, body and mind; and their preservation is the ultimate rationale for our existence. (1976, 20)

Noble then switches the analogy: Noble likens genes, not as having a “selfish” attribute, but to that of being “prisoners”, stuck in the body with no way of escape. Noble then says that, since there is no experiment to distinguish between the two views (which Dawkins admitted). Noble then concludes that, instead of being “selfish”, the physiological sciences look at genes as “cooperative”, since they need to “cooperate” with the environment, other genes, gene networks etc which comprise the whole organism.

In his 2018 book Agents and Goals in Evolution Samir Okasha distinguishes between type I and type II agential thinking. “In type 1 [agential thinking], the agent with the goal is an evolved entity, typically an individual organism; in type 2, the agent is ‘mother nature’, a personification of natural selection” (Okasha, 2018: 23). An example of type I agential thinking is Dawkins’ selfish genes, while type II is the personification that one imputes onto natural selection—which Okasha states that this type of thinking “Darwin was himself first to employ” (Okasha, 2018: 36) it.

Okasha states that each gene’s ultimate goal is to outcompete other genes—for that gene in question to increase its frequency in the organism. They also can have intermediate goals which is to maximize fitness. Okasha gives three rationales on what makes something “an agent”: (1) goal-directedness; (2) behavioral flexibility; and (3) adaptedness. So the “selfish” element “constitutes the strongest argument for agential thinking” of the genes (Okasha, 2018: 73). However, as Denis Noble has tirelessly pointed out, genes (DNA sequences) are inert molecules (and are one part of the developing system) and so do not show behavioral flexibility or goal-directedness. Genes can (along with other parts of the system working in concert with them) exert adaptive effects on the phenotype, though when genes (and traits) are coextensive, selection cannot distinguish between the fitness-enhancing trait and the free-riding trait so it only makes logical sense to claim that organisms are selected, not any individual traits (Fodor and Piatteli-Palmarini, 2010a, 2010b).

It is because of this, that the Neo-Darwinian gene-centric paradigm has failed, and is the reason why we need a new evolutionary synthesis. Some only wish to tweak the MS a bit in order to allow what the MS does not incorporate in it, but others want to overhaul the entire thing and extend it.

Here is the main reason why the MS fails: there is absolutely no reason to privilege any level of the system above any other! Causation is multi-level and constantly interacting. There is no a priori justification for privileging any developmental variable over any other (Noble, 2012, 2017). Both downward and upward causation exists in biological systems (which means that molecules depend on organismal context). The organism also able to control stochasticity—which is “used to … generate novelty” (Noble and Noble, 2018). Lastly, there is the creation of novelty at new levels of selection, like with how the organism is an active participant in the construction of the environment.

Now, what does the EES bring that is different from the MS? A whole bunch. Most importantly, it makes a slew of novel predictions. Laland et al (2016) write:

For example, the EES predicts that stress-induced phenotypic variation can initiate adaptive divergence in morphology, physiology and behaviour because of the ability of developmental mechanisms to accommodate new environments (consistent with predictions 1–3 and 7 in table 3). This is supported by research on colonizing populations of house finches [68], water fleas [132] and sticklebacks [55,133] and, from a more macro-evolutionary perspective, by studies of the vertebrate limb [57]. The predictions in table 3 are a small subset of those that characterize the EES, but suffice to illustrate its novelty, can be tested empirically, and should encourage deriving and testing further predictions.

[Table 3]

There are other ways to verify EES predictions, and they’re simple and can be done in the lab. In his book Above the Gene, Beyond Biology: Toward a Philosophy of Epigenetics, philosopher of biology Jan Baedke notes that studies of epigenetic processes which are induced in the lab and those that are observed in nature are similar in that they share the same methodological framework. So we can use lab-induced epigenetic processes to ask evolutionary questions and get evolutionary answers in an epigenetic framework. There are two problems, though. One, that we don’t know whether experimental and natural epigenetic inducements will match up; and two we don’t know whether or not these epigenetic explanations that focus on proximate causes and not ultimate causes can address evolutionary explananda. Baedke (2018: 89) writes:

The first has been addressed by showing that studies of epigenetic processes that are experimentally induced in the lab (in molecular epigenetics) and those observed in natural populations in the field (in ecological or evolutionary epigenetics) are not that different after all. They share a similar methodological framework, one that allows them to pose heuristically fruitful research questions and to build reciprocal transparent models. The second issue becomes far less fundamental if one understands the predominant reading of Mayr’s classical proximate-ultimate distinction as offering a simplifying picture of what (and how) developmental explanations actually explain. Once the nature of developmental dependencies has been revealed, the appropriateness of developmentally oriented approaches, such as epigenetics, in evolutionary biology is secured.

Further arguments for epigenetics from an evolutionary approach can be found in Richardson’s (2017) Genes, Brains, and Human Potential (chapter 4 and 5) and Jablonka and Lamb’s (2005) Evolution in Four Dimensions. More than genes alone are passed on and inherited, and this throws a wrench into the MS.

Some may fault DST for not offering anything comparable to Darwinisim, as Dupre (2003: 37) notes:

Critics of DST complain that it fails to offer any positive programme that has achievements comparable to more orthodox neo-Darwinism, and so far this complaint is probably justified.

But this is irrelevant. For if we look at DST as just a part of the whole EES programme, then it is the EES that needs to—and does—“offer a positive programme that has achievements comparable to more orthodox neo-Darwinism” (Dupre, 2003: 37). And that is exactly what the EES does: it makes novel predictions; it explains what needs to be explained better than the MS; and the MS has shown to be incoherent (that is, there cannot be selection on only one level; there can only be selection on the organism). That the main tool of the MS (natural selection) has been shown by Fodor to be vacuous and non-mechanistic is yet another strike against it.

Since DST is a main part of the EES, and DST is “a wholeheartedly epigenetic approach to development, inheritance and evolution” (Griffiths, 2015) and the EES incorporates epigenetic theories, then the EES will live or die on whether or not its evolutionary epigenetic theories are confirmed. And with the recent slew of books and articles that attest to the fact that there is a huge component to evolutionary epigenetics (e.g., Baedke, 2018; Bonduriansky and Day, 2018; Meloni, 2019), it is most definitely worth seeing what we can find in regard to evolutionary epigenetics studies, since epigenetic changes induced in the lab and those that are observed in natural populations in nature are not that different. This can then confirm or deconfirm major hypotheses of the EES—of which there are many. It is time for Lamarck to make his return.

It is clear that the MS is lacking, as many authors have pointed out. To understand evolutionary history and why organisms have the traits they do, we need much more than the natural selection-dominated neo-Darwinian Modern Synthesis. We need a new synthesis (which has been formulated for the past 15-20 years) and only through this new synthesis can we understand the hows and whys. The MS was good when we didn’t know any better, but the reductionism it assumes is untenable; there cannot be any direct selection on any level (i.e., the gene) so it is a nonsensical programme. Genes are not directly selected, nor are traits that enhance fitness. Whole organisms and their developmental systems are selected and propagate into future generations.

The EES (and DST along with it) hold right to the causal parity thesis—“that genes/DNA play an important role in development, but so do other variables, so there is no reason to privilege genes/DNA above other developmental variables.” This causal parity between all tools of development is telling: what is selected is not just one level of the system, as genetic reductionists (neo-Darwinists) would like to believe; it occurs on the whole organism and what it interacts with (the environment); environments are inherited too. Once we purge the falsities that were forced upon us by the MS in regard to organisms and their relationship with the environment and the MS’s assumptions about evolution as a whole, we can then truly understand how and why organisms evolve the phenotypes they do; we cannot truly understand the evolution of organisms and their phenotypes with genetic reductionist thinking with sloppy logic. So who wins? The MS does not, since it has causation in biology wrong. This only leaves us with the EES as the superior theory, predictor, and explainer.

The Human and Cetacean Neocortex and the Number of Neurons in it

2100 words

For the past 15 years, neuroscientist Suzanna Herculano-Houzel has been revolutionizing the way we look at the human brain. In 2005, Herculano-Houzel and Lent (2005) pioneered a new way to ascertain the neuronal make-up of brains: dissolving brains into soup and counting the neurons in it. Herculano-Houzel (2016: 33-34) describes it so:

Because we [Herculano-Houzel and Lent] were turning heterogeneous tissue into a homogeneous—or “isotropic”—suspension of nuclei, he proposed we call it the “isotropic fractionator.” The name stuck for lack of any better alternative. It has been pointed out to me by none other than Karl Herrup himself that it’s a terribly awkward name, and I agree. Whenever I can (which is not often because journal editors don’t appreciate informality), I prefer to call our method of counting cells what it is: “brain soup.”

So, using this method, we soon came to know that humans have 86 billion neurons. This flew in the face of the accepted wisdom—humans have 100 billion neurons in the brain. However, when Herculano-Houzel searched for the original reference for this claim, she came up empty-handed. The claim that we have 100 billion neurons “had become such an established “fact” that neuroscientists were allowed to start their review papers with generic phrases to that effect without citing references. It was the neuroscientist’s equivalent to stating that genes were made of DNA: it had become a universally known “fact” (Herculano-Houzel, 2016: 27). Herculano-Houzel (2016: 27) further states that “Digging through the literature for the original studies on how many cells brains are made of, the more I read, the more I realized that what I was looking for simply didn’t exist.”

So this “fact” that the human brain was made up of 100 billion neurons was so entrenched in the literature that it became something like common knowledge—for instance, that the sun is 93 million miles away from earth—that did not need a reference in the scientific literature. Herculano-Houzel asked her co-author of her 2005 paper (Roberto Lent) who authored a textbook called 100 Billion Neurons if he knew where the number came from, but of course he didn’t know. Though, subsequent editions added a question mark, making the title of the text 100 Billion Nuerons? (Herculano-Houzel, 2016: 28).

So using this method, we now know that the cellular composition of the human brain is expected for a brain our size (Herculano-Houzel, 2009). According to the encephilization quotient (EQ) first used by Harry Jerison, humans have an EQ of between 7 and 8—the largest for any mammal. And so, since humans are the most intelligent species on earth, this must account for Man’s exceptional abilities. But does it?

Herculano-Houzel et al (2007) showed that it wasn’t humans, as popularly believed, that had a larger brain than expected, but it was great apes, more specifically orangutans and gorillas that had bodies too big for their brains. So the human brain is nothing but a linearly scaled-up primate brain—humans have the amount of neurons expected for a primate brain of its size (Herculano-Houzel, 2012).

So Herculano-Houzel (2009) writes that “If cognitive abilities among non-human primates scale with absolute brain size (Deaner et al., 2007 ) and brain size scales linearly across primates with its number of neurons (Herculano-Houzel et al., 2007 ), it is tempting to infer that the cognitive abilities of a primate, and of other mammals for that matter, are directly related to the number of neurons in its brain.” Deaner et al (2007) showed that cognitive ability in non-human primates “is not strongly correlated with neuroanatomical measures that statistically control for a possible effect of body size, such as encephalization quotient or brain size residuals. Instead, absolute brain size measures were the best predictors of primate cognitive ability.” While Herculano-Houzel et al (2007) showed that brain size scales linearly across primates with the number of neurons—so as brain size increases so does the neuronal count of that primate brain.

This can be seen in Fonseca-Azevedo’s and Herculano-Houzel’s (2012) study on the metabolic constraints between humans and gorillas. Humans cook food while great apes eat uncooked plant foods. Larger animals have larger brains, more than likely. However, gorillas have larger bodies than we do but smaller brains than expected while humans have a smaller body and bigger brain. This is due to the diet that the two species eat—gorillas spend about 8-10 hours per day feeding while, if humans had the same number of nuerons but ate a raw, plant-based diet, they would need to feed for about 9 hours a day to be able to sustain a brain with that many neurons. This, however, was overcome by Homo erectus and his ability to cook food. Since he could cook food, he could afford a large brain with more neurons. Fonseca-Azevedo and Herculano-Houzel (2012) write that:

Given the difficulties that the largest great apes have to feed for more than 8 h/d (as detailed later), it is unlikely, therefore, that Homo species beginning with H. erectus could have afforded their combinations of MBD and number of brain neurons on a raw diet.

That cooking food leads to a greater amount of energy unlocked can be seen with Richard Wrangham’s studies. Since the process of cooking gelatinizes the protein in meat, it makes it easier to chew and therefore digest. This same denaturization of proteins occurs in vegetables, too. So, the claim that cooked food (a form of processing, along with using tools to mash food) has fewer calories (kcal) than raw food is false. It was the cooking of food (meat) that led to the expansion of the human brain—and of course, allowed our linearly scaled-up primate brain to be able to afford so many neurons. Large brains with a high neuronal count are extraordinarily expensive, as shown by Fonseca-Azevedo and Herculano-Houzel (2012).

Erectus had smaller teeth, reduced bite force, reduced chewing muscles and a relatively smaller gut compared to other species of Homo. Fink and Lieberman (2016) show that slicing and mashing meat and underground storage organs (USOs) would decrease the number of chews per year by 2 million (13 percent) while the total masticatory force would be reduced about 15 percent. Further, by slicing and pounding foodstuffs into 41 percent smaller particles, the number of chews would be reduced by 5 percent and the masticatory force reduced by 12 percent. So, of course, it was not only cooking that led to the changes we see in erectus compared to others, it was also the beginning of food processing (slicing and mashing are forms of processing) which led to these changes. (See also Catching Fire: How Cooking Made Us Human by Wrangham, 2013 for the evidence that cooking catapulted our brains and neuronal capacity to the size it is now, along with Wrangham, 2017.)

So, since the neuronal count of a brain is directly related to the cognitive ability that brain is capable of, then since Herculano-Houzel and Kaas (2011) showed that since the modern range of neurons was found in heidelbergensis and neanderthalensis, that they therefore had similar cognitive potential to us. This would then mean that “Compared to their societies, our outstanding accomplishments as individuals, as groups, and as a species, in this scenario, would be witnesses of the beneficial effects of cultural accumulation and transmission over the ages” (Herculano-Houzel and Kaas, 2011).

The diets of Neanderthals and humans, while similar (and differed due to the availability of foods), nevertheless, is a large reason why they have such large brains with a large number of neurons. Though, it must be said that there is no progress in hominin brain evolution (contra the evolutionary progressionists) as brain size is predicated on the available food and nutritional quality (Montgomery et al, 2010).

But there is a problem for Herculano-Houzel’s thesis that cognitive ability scales-up with the absolute number of neurons in the cerebral cortex. Mortensen et al (2014) used the optical fractionator (not to be confused with the isotropic fractionator) and came to the conclusion that “the long-finned pilot whale neocortex has approximately 37.2 × 109 neurons, which is almost twice as many as humans, and 127 × 109 glial cells. Thus, the absolute number of neurons in the human neocortex is not correlated with the superior cognitive abilities of humans (at least compared to cetaceans) as has previously been hypothesized.” This throws a wrench in Herculano-Houzel’s thesis—or does it?

There are a couple of glaring problems here, most importantly, I do not see how many slices of the cortex that Mortensen et al (2014) studied. They refer to the flawed stereological estimate of Eriksen and Pakkenberg (2007) showed that the Minke whale had an estimated 13 billion neurons while Walloe et al (2010) showed that the harbor porpoise had 15 billion cortical neurons with an even smaller cortex. These three studies are all from the same research team who use the same stereological methods, so Hercualano-Houzel’s (2016: 104-106) comments apply:

However, both these studies suffered from the same unfortunately common problem in stereology: undersampling, in one case drawing estimates from only 12 sections out of over 3,000 sections of the Minke whale’s cerebral cortex, sampling a total of only around 200 cells from the entire cortex, when it is recommended that around 700-1000 cells be counted per individual brain structure. with such extreme undersampling, it is easy to make invalid extrapolations—like trying to predict the outcome of a national election by consulting just a small handful of people.

It is thus very likely, given the undersampling of these studies and the neuronal scaling rules that apply to cetartiodactyls, that even the cerebral cortex of the largest whales is a fraction of the average 16 billion neurons that we find in the human cerebral cortex.

[…]

It seems fitting that great apes, elephants, and probably cetaceans have similar numbers of neurons in the cerebral cortex, in the range of 3 to 9 billion: fewer than humans have, but more than all other mammals do.

Kazu et al (2014) state that “If the neuronal scaling rules for artiodactyls extend to all cetartiodactyls, we predict that the large cerebral cortex of cetaceans will still have fewer neurons than the human cerebral cortex.” Artiodactyls are cousins of cetaceans—and the order is called cetariodactyls since it is thought that whales evolved from artiodactyls. So if they did evolve from artiodactyls, then the neruonal scaling rules would apply to them (just as humans have evolved from other primates and the neuronal scaling rules apply to us). So the predicted “cerebral cortex of Phocoena phocoena, Tursiops truncatus, Grampus griseus, and Globicephala macrorhyncha, at 340, 815, 1,127, and 2,045 cm3, to be composed of 1.04, 1.75, 2.11, and 3.01 billion neurons, respectively” (Kazu et al, 2014). So the predicted number of cerebellar neurons in the pilot whale is around 3 billion—nowhere near the staggering amount that humans have (16 billion).

Humans have the most cerebellar neurons of any animal on the planet—and this, according to Herculano-Houzel and her colleagues, accounts for the human advantage. Studies that purport to show that certain species of cetaceans have similar—or more—cereballar neurons than humans rest on methodological flaws. The neuronal scaling rules that Herculano-Houzel and colleagues have for cetaceans predict far, far fewer cortical neurons in the species. It is for this reason that studies that show similar—or more—cortical neurons in other species that do not use the isotropic fractionator must be looked at with extreme caution.

However, when Herculano-Houzel and colleagues do finally use the isotropic fractionator on pilot whales, and if their prediction does not come to pass but falls in-line with that of Mortensen et al (2014), this does not, in my opinion, cast doubt on her thesis. One must remember that cetaceans have completely different body plans from humans—most glaringly, the fact that we have hands to manipulate the world with. However, Fox, Muthukrishna, and Shultz (2017) show that whales and dolphins have human-like cultures and societies while using tools and passing down that information to future generations—just like humans do.

In any case, I believe that the prediction borne out from Kazu et al (2014) will show substantially fewer cortical neurons than in humans. There is no logical reason to accept the cortical neuronal estimates from the aforementioned studies since they undersampled parts of the cortex. Herculano-Houzel’s thesis still stands—what sets humans a part from other animals is the number of neurons which is tightly packed in to the cerebral cortex. The human brain is not that special.

The human advantage, I would say, lies in having the largest number of neurons in the cerebral cortex than any other animal species has managed—and it starts by having a cortex that is built in the image of other primate cortices: remarkable in its number of neurons, but not an exception to the rules that govern how it is put together. Because it is a primate brain—and not because it is special—the human brain manages to gather a number of neurons in a still comparatively small cerebral cortex that no other mammal with a viable brain, that is, smaller than 10 kilograms, would be able to muster. (Herculano-Houzel, 2016: 105-106)