Controversies and the Shroud of Turin

2000 words

Introduction

The Shroud of Turin is a long cloth that bears the negative image of a man that was purportedly crucified. The study of the Shroud even has its own name—sindonology. The Shroud, ever since its discovery, has been the source of rampant controversy. Does the Shroud show a crucified man? Is this man Christ after the crucifixion? Is the Shroud real or is it a hoax? For centuries these questions have caused long and drawn-out debate. Fortunately, recent analyses seem to have finally ended this centuries-old question: “Does the Shroud of Turin show Christ after the crucifixion?” In this review, I will discuss the history of the Shroud, the pro- and the con-side of the Shroud and what, if any, bearing it has any on the truth of Christianity. The Shroud has been marred in controversy ever since its appearance in the historical record, and for good reason. If it can be proven that the Shroud was Christ’s burial linen and if it can be proven that, somehow, Christ’s image, say, became imprinted when his spirit left his body, this would lend credence to claims from Christians and Catholics—but reality seems to bear different facts of the matter from these claims.

Various theories of the Shroud have been put forth to explain the image that appears when a negative picture is taken of the Shroud. From people hypothesizing that the great Italian artist da Vinci drew it on the cloth (Picknett and Prince, 2012), to it actually being the blood-soaked burial cloth of Christ himself, to its being just a modern-day forgery, we now have the tools in the modern-day to carry out analyses to answer these questions and put them to rest for good.

The history of the Shroud dates back to around the 1350s, as the Vatican historian Barbara Frale notes in her book The Templars and the Shroud of Christ: A Priceless Relic in the Dawn of the Christian Era and the Men Who Swore to Protect It (Frale, 2015). Meachem (1983) discusses how the Shroud has generated controversy ever since it was put on display in 1357 in France. That the Shroud first appeared in written records in the 1350s does not, however, mean that the Shroud is not Christ’s burial linen.

Some, even back when the Shroud was discovered, argued that it was just a painting on linen cloth. As McCrone (1997: 180) writes “The arrangement of pigment particles on the “Shroud” is […] completely consistent with painting with a brush using a water-color paint.” So this would lend credence to the claim that the Shroud is nothing but a painting—most likely a medieval one.

The Shroud itself is around 14’3” long (Crispino, 1979) and, believers claim, it dates back to two millennia ago and bears the imprint of Jesus Christ. It is currently housed at the Cathedral of Saint John the Baptist in Turin, Italy. The Shroud shows what appears to be a tall man, though Crispino (1979) shows that there have been many height estimates of the man on the Shroud, estimates ranging between 5’3.5” to 6’1.5”. With such wide-ranging height estimates, it is therefore unlikely that we will get an agreed-upon height measurement of the man on the Shroud. But Crispino (1979) does note that estimates of Palestinian males 2000 years ago were between 5’1” to 5’3”, and so, if this were Christ’s burial cloth, then it stands to reason that the man would be closer to the lower bound noted by Crispino (1979).

The Shroud shows a man who seems to bear the marks of the crucifixion. If the Shroud was really the burial cloth of a man who was crucified, then there would be blood on the linen. There are blood spots on the Shroud, and there have been recent tests on the cloth to see if it really is human blood.

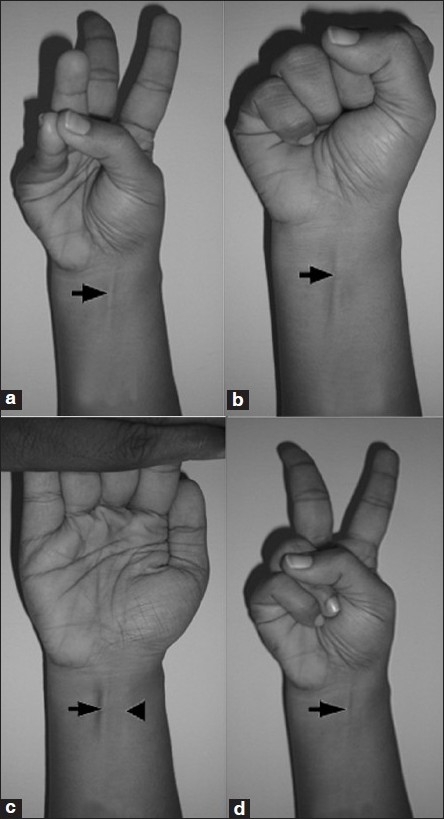

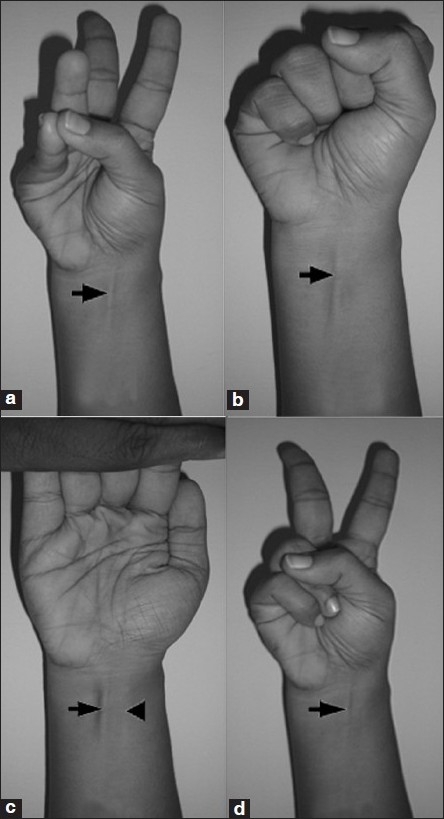

A method called blood pattern analysis (BPA) is a very useful—ingenious—way to ascertain whether or not the veracity of the claim that the Shroud really was Christ’s burial cloth is true. BPA “refers to the collection, categorization and interpretation of the shape and distribution of bloodstains connected with a crime” (Peschel et al, 2010). By using a model and draping a cloth over them and using the same wounds that Christ was said to have, we can glean—with good accuracy—if the claim that the Shroud was Christ’s burial cloth is true.

A recent study using BPA was undertaken, to ascertain whether or not the blood stains on the Shroud are realistic, and not just art (Borrini and Garleschelli, 2018). They used a living subject to see if the blood patterns on the cloth are realistic. Their analysis showed that “blood visible on the frontal side of the chest (the lance wound) shows that the Shroud represents the bleeding in a realistic manner for a standing position” whereas the stains on the back were “totally unrealistic.”

Zugibe (1989) also puts forth a scientific hypothesis: the claim that Christ was washed prior to his being rolled in the linen cloth that is the Shroud we know of today. So, if Christ were washed before being placed in the linen, then it would lend veracity to the claim that the Shroud truly is Christ’s burial linen. Citing the apocryphal text The Lost Gospel According to Peter, Zugibe (1989) provides scriptural evidence for the claim that Christ was washed before death, which lends credence to the hypothesis that the Shroud truly is Christ’s burial linen. Zugibe (1989) clearly shows that, even after a body has been washed, it can still bleed profusely, which may have caused the blood stains on the Shroud.

Indeed, even Wilson (1998: 235) writes that “ancient blood specialist Dr Thomas Loy confirm[s] that blood many thousands of years old can remain bright red in certain cases of traumatic death.” This coheres well with Zugibe’s (1989) argument that in certain cases, even after a body has been washed and wrapped in linen, that there can still be apparent blood stains on the linen (and we know from Biblical accounts that Jesus did die a traumatic death).

To really see if the Shroud truly is the burial cloth of Christ, analyses of the linen can be undertaken to ascertain an average range of time for when the linen was made. There have been analyses of the linen, and the dates that we get are between the 1250s to 1350s. However, those who believe that the Shroud is truly the burial cloth of Christ state that the fibers that were tested were taken from medieval repairs of the cloth, since one of the locations the cloth was housed in burned down due to a fire in 1532 (Adler, 1996), causing damage to the cloth. For example, Rogers (2005) argues that the threads of linen tested were from medieval repairs, and that the true date of the Shroud is between 1300 and 3000 years old.

Barcaccia et al (2015) undertook an analysis of some dust particles on the back of the Shroud by vacuuming them. They found that there were multiple, non-native plant species on the Shroud, along with multiple mtDNA (mitochondrial DNA) haplogroups (H1-3, H13/H2a, L3C, H33, R0a, M56, and R7/R8). However, the fact that multiple mtDNA halpogroups were found on the Shroud is consistent with the fact that the Shroud took many journeys throughout its time, before ending up in Turin, Italy. It could also reflect the fact that numerous contemporary researchers’ DNA has contaminated the Shroud as well. In any case, Barcaccia et al (2015) show that there were numerous species of plants from all around the world along with many different kinds of mtDNA, and so, both believers and skeptics can use this study as evidence for their side. Barcaccia et al (2015) conclude that the Shroud may have been weaved in India, due to its original name Sindon, which is a fabric from India—which mtDNA analyses corroborate.

There is even evidence that the face on the Shroud is that of da Vinci himself. Artist Lillian Schwartz, using computer imaging, showed that the facial dimensions on the Shroud matched up to the facial dimensions of da Vinci (Jamieson, 2009). It is hypothesized that da Vinci used what is called a camera obscura to put his facial features onto the Shroud. Since we know that da Vinci made some ultra-realistic drawings of the human body since he had access to the morgue (Shaikh, 2015), then it is highly plausible that da Vinci himself was responsible for the image on the Shroud. Jamieson (2009) states that, in the documentary that explains how da Vinci created the Shroud: the most likely way for it to have been made was hanging the Shroud in a dark room with silver sulfate. So when the sun’s rays went through a lens on the wall, da Vinci’s face would have been burnt into it.

Further, there are some arguments that state that the man on the Shroud is not Christ, but is, in fact, the Jacque de Molay—the last Grand Master of the Knights Templar. If the claim turns out to be true, this could be why the Knights protected the Shroud so fervently. Although there is little historical evidence as to how Molay was tortured, we do know he was tortured. Though what is also interesting is that apparently Molay was put through the same exact process of crucifixion that Christ was said to have gone through. If this is the case, then that could explain the same marks in the hands and blood on the Shroud that would have been on the Shroud had Christ been the one crucified and wrapped in the linen that eventually became the Shroud. Though, those who were to kill Molay were “expressly forbidden to shed blood“, though we know he was tortured, it is not out of the realm of possibility that he did bleed after death. Molay was killed in 1317 C.E., and this lines up with the accounts from Frale (2015) and Meachem (1983) that the Shroud appeared around the 1350s. So the Knights protecting the Shroud as they did—even if it were not Christ—would have some backing.

Discussion

The validity of the Shroud is quite obviously a hot-button topic for Catholics. No matter the outcome of any study on the matter, they can concoct an ad-hoc hypothesis to immunize their beliefs from falsification. No doubt, some of the critiques they bring up are valid (e.g., that they are taking fibers of linen from restored parts of the Shroud), though, after so many analyses one would have to reason that the hypothesis that the Shroud truly was Christ’s burial cloth is false. Furthermore, even if the Shroud is dated back to the 1st century, that would not be evidence that the Shroud was Christ’s burial shroud. The mtDNA analyses also seem to establish that the Shroud passed through many hands—as the hypothesis predicts. However, this also coheres with the explanation that it was made during medieval times, with numerous people touching the linen that eventually ended up becoming the Shroud. It is also, of course, not out of the realm of possibility that contemporary researchers have contaminated the Shroud with their own DNA, making objective genomic analyses of the Shroud hard to verify, while there would be no way to partition contaminated DNA from DNA that was originally on the Shroud.

In any case—irrespective of the claims of those who wish that this is Christ’s burial cloth and thus will concoct any ad-hoc hypothesis to immunize their beliefs from falsification—it seems to be the case that the Shroud was not Christ’s burial cloth. On the basis of mtDNA analyses, blood pattern analyses (which seem to point to the fact that it is an artistic representation of Christ’s burial), to the evidence that facial dimensions on the Shroud match up with da Vinci’s face, the apparent claims that the Shroud was the last Grand Master of the Knights Templar, along with the fact that the original name of the Shroud was Indian in origin, all point to the fact that the Shroud was, in fact, not Christ’s burial linen, no matter how fervent believers are about the veracity of the claim.

The Distinction Between Action and Behavior

1300 words

Action and behavior are distinct concepts, although in common lexicon they are used interchangeably. The two concepts are needed to distinguish what one intends to do and what one reacts to and how they react. In this article, I will explain the distinction between the two and how and why people get it wrong when discussing the two concepts—since using them interchangeably is inaccurate.

Actions are intentional; they are done for reasons (Davidson, 1963). Actions are determined by one’s current intentional state and they then act for reasons. So, in effect, the agent’s intentional states cause the action, but the action is carried out for reasons. Actions are that which is done by an agent, but stated in this way, it could be used interchangeably with behavior. The Wikipedia article on “action” states:

action is an intentional, purposive, conscious and subjectively meaningful activity

So actions are conscious, compared to behaviors which are reflexive and unconscious—not done for reasons.

Davidson (1963: 685) writes:

Whenever someone does something for a reason, therefore, he can be characterized as (a) having some sort of pro attitude toward actions of a certain kind, and (b) believing (or knowing, perceiving, noticing, remembering) that his action is of that kind.

So providing the reason why an agent did A requires naming the pro-attitude—beliefs paired with desires—or the related belief that caused the agent’s action. When I explain behavior, this will become clear.

Behavior is different: behavior is a reaction to a stimulus and this reaction is unconscious. For example, take a doctor’s office visit. Hitting the knee in the right spot causes the knee to jerk up—doctors use this test to test for nerve damage. It tests the L2, L3, and L4 segments of the spinal cord, so if there is no reflex, the doctor knows there is a problem.

This is done without thought—the patient does not think about the reflex. This then shows how and why action and behavior are distinct concepts. Here’s what occurs when the doctor hits the patient’s knee:

When the doctor hits the knee, the patient’s thigh muscle stretches. When the thigh muscle stretches, a signal is then sent along the sensory neuron to the spinal cord where it interacts with a motor neuron which goes to the thigh muscle. The muscle then contracts which causes the reflex. (Recall my article on causes of muscle movement.)

So this, compared to consciously taking a step—consciously jerking your leg in the same way as a doctor expects the patellar reflex—is what distinguishes one from the other—what distinguishes action from behavior. Sure, the behavior of the patellar reflex occurred for a reason—but it was not done consciously by the agent so it is therefore not an action.

Perhaps it would be important at this point to explain the differences between action, conduct, and behavior, because we have used these three terms in the discussion of caring. …

Teleology, the reader is reminded, involves goals or lures that provide the reasons for a person acting in a certain way. It is goals or reasons that establish action from simple behavior. On the other hand the concept of efficient causation is involved in the concept of behavior. Behavior is the result of antecedent conditions. The individual behaves in response to causal stimuli or antecedent conditions. Hence, behavior is a reaction to what already is—the result of a push from the past to do something in the present. In contrast, an action aims at the future. It is motivated by a vision of what can be. (Brencick and Webster, 2000: 147)

This is also another thing that Darwin got wrong. He believed that instincts and reflexes are inherited—this is not wrong since they are behaviors and behaviors are dispositional which means they can be selected. However, he believed that before they were inherited as instincts and reflexes, they were intentional acts. As Badcock (2000: 56) writes in Evolutionary Psychology: A Critical Introduction:

Darwin explicitly states this when he says that ‘it seems probable that some actions, which were at first performed consciously, have become through habit and association converted into relex actions, and are now firmly fixed and inherited.’

This is quite obviously wrong, as I have explained above; instead of “reflexive actions”, Darwin meant “reflexive behaviors”. So, it seems that Darwin did not grasp the distinction between “action” and “behavior” either.

We can then form this simple argument, take cognition:

(1) Cognition is intentional;

(2) Behavior is dispositonal;

(3) Therefore, cognition is not responsible for behavior

This is a natural outcome of what has been argued here, due to the distinction between action and behavior. So when we think of “cognition” what comes to mind? Thinking. Thinking is an action—so thinking (cognition) is intentional. Intentionality is “the power of minds and mental states to be about, to represent, or to stand for, things, properties and states of affairs.” So, when we think, our minds/mental states can represent, stand for things, properties and states of affairs. Therefore, cognition is intentional. Since cognition is intentional and behavior is dispositional, it directly follows that cognition cannot be responsible for behavior.

Thinking is a mental activity which results in a thought. So if thinking is a mental activity which results in a thought, what is a thought? A thought is a mental state of considering a particular idea or answer to a question or committing oneself to an idea or answer. These mental states are, or are related to, beliefs. When one considers a particular answer to a question they are paving the way to holding a particular belief; when they commit themselves to an answer they have formulated a new belief.

Beliefs are propositional attitudes: believing p involves adopting the belief attitude to proposition p. So, cognition is thinking: a mental process that results in the formation of a propositional belief. When one acquires a propositional attitude by thinking, a process takes place in stages. Future propositional attitudes are justified on earlier propositional attitudes. So cognition is thinking; thinking is a mental state of considering a particular view (proposition).

Therefore, thinking is an action (since it is intentional) and cannot possibly be a behavior (a disposition). Something can be either an action or a behavior—it cannot be both.

Let’s say that I have the belief that food is downtown. I desire to eat. So I intend to go downtown to get some food. While the cause is the sensation of hunger. This chain shows how actions are intentional—how one intends to act.

Furthermore, using the example I explained above, how a doctor assesses the patellar reflex is a behavior—it is not an action since the agent himself did not cause it. One could say that it is an action for the doctor performing the reflexive test, but it cannot be an action for the agent the test is being done on—it is, therefore, a behavior.

I have explained the difference between action and behavior and how and why they are distinct. I gave an example of action (cognition) and behavior (patellar reflex) and explained how they are distinct. I then gave an argument showing how cognition (an action) cannot possibly be responsible for behavior. I showed how Darwin believed (falsely) that actions could eventually become behaviors. Darwin pretty much stated “Actions can be selected and eventually become behaviors.” This is nonsense. Actions, by virtue of being intentional, cannot be selected, even if they are done over and over again, they do not eventually become behaviors. On the other hand, behavior, by virtue of being dispositional, can be selected. In any case, I have definitively shown that the two concepts are distinct and that it is nonsense to conflate the terms.

Snapchat Dysmorphia

1450 words

I’m not really one for social media (the only social media I use is Twitter and this blog) and so I don’t keep up with the new types of social media that continuously pop up. Snapchat has been around since 2011. It’s a type of social media where users can share pictures before they are then unavailable to the user they sent it to. I don’t understand the utility of media like this but maybe that’s because I’m not the target demographic.

In any case, I’m not going to talk about Snapchat in that way today, because that’s not what this blog is about. What I will talk about today, though, is the rise of “Snapchat dysmorphia.” “Dysmorphia” is defined by the Merriam Webster Dictionary as “characterized by malformation.” “Dysphoria”, according to the Merriam Webster Dictionary, is defined as “a state of feeling very unhappy, uneasy, or dissatisfied.” This is a type of body dysmorphia. The two terms—dysphoria and dysmorphia—are similar, in any case.

So where does Snapchat come into play here? Well, there are certain functions that one can do with their pictures—and I’m sure they can do the same with other applications as well. There are what I would term “picture editors” which can change how a person looks. From changing the background you’re in, to changing your facial features, there are a wide range of things these kinds of filters can generate onto photographs/videos.

Well, of course, with the rise of social media and people constantly being glued to their phones day in and day out—along with pretty much living their entire lives on social media—people get sucked into the digital world they make for themselves. People constantly send pictures to others about what they’re doing on that day—they don’t have a chance to live in the moment because they’re always trying to get the “best picture” of the moment they’re in, since they’re trying to get the best picture for their followers on social media. In any case, this is where the problem with these kinds of filters come in—and how Snapchat is driving these problems.

So people use these filters on their pictures. They then get used to seeing themselves as they see themselves in the filtered pictures. Since they spend so much time on social media, constantly filtering their pictures, they—and their social media followers—get used to seeing their filtered photos and not how they really like. This, right here, is the problem.

People then become dysphoric—they become unsatisfied with their appearance due to how they look in their filtered photos. This has lead numerous people to do what I believe is insane—they go and get plastic surgery to look like their Snapchat selves. This is, in part, what the meteoric rise of social media has done to the minds of the youth. They give them unrealistic expectations—through their filters—and then, since they spend so much time Snapchatting and whatever else they do, seeing their filtered pictures, they then get sad that they do not look like they do in their filtered pictures in their digital world, which causes them to become dysphoric about their facial features since they do not look like their Snapchat selves.

One Snapchat user said to Vice:

We’d rather have a digitally obscured version of ourselves than our actual selves out there. It’s honestly sad, but it’s a bitter reality. I try to avoid using them as much as I can because they seriously cause an unhealthy dysphoria.

Therein lies the problem: people become used to what I would say are “idealized versions” of themselves. Some of these filters completely change how one’s facial structure is; some of them give bigger or smaller eyes; others change the shape of the jawline and cheekbones; others give fuller lips. So now, instead of people bringing photographs of celebrities to plastic surgeons and saying to them “This is what I want to look like”, they’re bringing their edited Snapchat pictures to plastic surgeons and telling them that they want that look.

So it’s no wonder that people become dysphoric about their facial features when they pretty much live on social media. They constantly play around with this filter and that filter, and they become used to what then becomes an idealized version of themselves. These types of picture filters have been argued to be bad for self-esteem, and it’s no wonder why they are, given the types of things these filters can do to radically change the appearances of the users who use them.

There has been a rise in individuals bringing in their filtered photos to plastic surgeons, telling them that they want to look like the filtered picture. Indeed, some of the before and afters I have seen bear striking similarities to the filtered photo.

The term “Snapchat dysmorphia” has even made it into the journal JAMA in an article titled Selfies—living in the era of filtered photographs (Rajanala, Maymobe, and Vashi, 2018). They write that:

Previously, patients would bring images of celebrities to their consultations to emulate their attractive features. A new phenomenon, dubbed “Snapchat dysmorphia,” has patients seeking out cosmetic surgery to look like filtered versions of themselves instead, with fuller lips, bigger eyes, or a thinner nose.

Ramphus and Mejias (2018) state that while it may be too early to employ the term “Snapchat dysmorphia”, it is imperative to realize the reasons why many young people are thinking and getting plastic surgery. Indeed, a few plastic surgeons have stated that the type of alterations that patients describe to them, indeed, are what are found with Snapchat facial edits.

Ramphul and Mejias (2018) also write:

There are already some ongoing legal issues about the use of Snapchat in the operating room by some plastic surgeons but none currently involving any patients accusing Snapchat of giving them a false perception of themselves yet. The proper code of ethics among plastic surgeons should be respected and an early detection of associated symptoms in such patients might help provide them with the appropriate counseling and help they need.

Clearly, this issue is now becoming large enough that medical journals are now employing the term in their articles.

McLean et al’s (2015) results “showed that girls who regularly shared self-images on social media, relative to those who did not, reported significantly higher overvaluation of shape and weight, body dissatisfaction, dietary restraint, and internalization of the thin ideal. In addition, among girls who shared photos of themselves on social media, higher engagement in manipulation of and investment in these photos, but not higher media exposure, were associated with greater body-related and eating concerns, including after accounting for media use and internalization of the thin ideal.” This seems intuitive: the more time one spends on social media, sharing images, overvalues certain things. And putting this into context in regard to Snapchat dysmorphia, girls spending too much time on these types of applications that can change their appearance, may also develop eating disorders.

Ward et al (2018) report that in 2014, about 93 million selfies were taken per day. With the way selfies are taken—up close—this then distorts the nasal dimensions, increasing them (Ward et al, 2018). Although this is only tangentially related to the issue of Snapchat dysmorphia, it will also increase the chance of people seeking plastic surgery, since a lot of people spend so much time on social media, taking selfies and eventually idealizing their selves with the angles they take the pictures in.

Although there are only 2 pages on Google scholar when you search “Snapchat dysmorphia”, we can expect the number of journal articles and references to the term to increase in the coming years due to people basically living most of their lives on social media. This is troubling: that young people are spending so much time on social media, editing their photos and acquiring dysmorphia due to the types of edits that are possible with these applications is an issue that we will need to soon address. Quite obviously, getting plastic surgery to look more like the idealized Snapchat photo is not the solution to the problem—something more like counseling or therapy would seem to address the issue. Not pretty much telling people “If you have the money and the time to get this surgery done then you should, to look like how you idealize yourself.”

Should people get plastic surgery to fix their selves, or should they get counseling? People who look to, or get, survey to fix dysmorphic issues they have with themselves will never be satisfied. They will always see a blemish, an imperfection to fix. For this reason, getting surgery in an attempt “fix” yourself if addicted to your looks while using these picture filters won’t work, as the deeper problem isn’t addressed—which I would claim is rampant social media use.

Against Scientism

1350 words

Scientism is the belief that only scientific claims are meaningful, that science is the only way for us to gain knowledge. However, this is a self-refuting claim. The claim that “only scientific claims are meaningful” cannot be empirically observed, it is a philosophical claim. Thus, those who push scientism as the only way to gain knowledge fail, since the claim itself is a philosophical one. Although science (and the scientific method) do point us in the direction to gain knowledge, it is not the only way for us to gain knowledge. We can, too, gain knowledge through logic and reasoning. The claim that science and science along can point us towards objective facts about knowledge and reality is false.

There is no doubt about it: the natural sciences have pointed us toward facts, facts of the matter that exist in nature. However, this truth has been used in recent times to purport that the sciences are the only way for us to gain knowledge. That, itself, is a philosophical claim and cannot be empirically tested, and so it is self-defeating. Furthermore, the modern sciences themselves arose from philosophy.

Richard Dawkins puts forth a view of epistemology in his book The Magic of Reality in which all of the knowledge concerning reality is derived from our five senses. So if we cannot smell it, hear it, touch it, or taste it, we cannot know it. Thus, how we know what is true or not always comes back to our senses. The claim is “All knowledge of reality is derived from our senses.” There is a problem here, though: this is a philosophical claim and cannot be verified with the five senses. What a conundrum! Nothing that one can see, hear, taste or touch can verify that previous claim; it is a philosophical, not scientific claim and, therefore, the claim is self-refuting.

Science is dependent on philosophy, but philosophy is not dependent on science. Indeed, even the question “What is science?” is a philosophical, not scientific, question and cannot be known through the five senses. Even if all knowledge is acquired through the senses, the belief that all knowledge is acquired through the senses is itself not a scientific claim, but a philosophical one, and is therefore self-refuting.

In his book I am Not a Brain: Philosophy of Mind for the 21st Century, philosopher Markus Gabriel writes (pg 82-83):

The question of how we conceive of human knowledge acquisition has many far-reaching consequences and does not concern merely philosophical epistemology. Rampant empiricism — i.e., the thesis that all knowledge derives exclusively from sense experience — means trouble. If all knowledge stemmed from experience, and we could hence never really know anything definitively — since experience could always correct us — how could we know, for example, that one should not torture children or that political equality should be a goal of democratic politics? If empiricism were correct, how would we be supposed to know that 1 + 2 = 3, since it is hard to see how this could be easily revised by sense experience? How could we know on the basis of experience that we know everything only on the basis of experience?

Rampant empiricism breaks down in the face of simple questions. If all knowledge really stems from the source of sense experience, what are we supposed to make of the knowledge concerning this supposed fact? Do we know from sense experience that all knowledge stems from sense experience? One would then have to accept that experience can teach us wrongly even in regard to this claim. In principle, one would have to be able to learn through experience that we cannot learn anything through experience … How would this work? What kind of empirical discovery would tell us that not everything we know is through empirical discovery?

The thing is, the claim that “All knowledge stems from sense experience” cannot be corrected by sense experience, and so, it is not a scientific hypothesis that can be proven or disproven. No matter how well a scientific theory is established, it can always be revised and or refuted and pieces of evidence can come out that render the theory false. Therefore, what Gabriel terms “rampant empiricism” (scientism) is not a scientific hypothesis.

Scientism is believed to be justified on the basis of empirical discoveries and the fact that our senses can lead to the refutation or revision of these scientific theories. That in and of itself justifies scientism for most people. Though, as previously stated, that belief is a philosophical, not scientific, belief and cannot be empirically tested and is therefore self-refuting. Contemporary scientists and pundits who say, for example, that “Philosophy is dead” (i.e., Hawking and de Grasse Tyson) made philosophical claims, therefore proving that “Philosophy is not dead”!

Claims that science (empiricism) is the be-all-end-all for knowledge acquisition fall flat on their face; for if something is not logical, then how can it be scientifically valid? This is further buttressed by the fact that all science is philosophy and science needs philosophy, whereas philosophy does not need science since philosophy has existed long before the natural sciences.

Haak (2009: 3) articulates six signs of scientism:

1. Using the words “science,” “scientific,” “scientifically,” “scientist,” etc., honorifically, as generic terms of epistemic praise.

2. Adopting the manners, the trappings, the technical terminology, etc., of the sciences, irrespective of their real usefulness.

3. A preoccupation with demarcation, i.e., with drawing a sharp line between genuine science, the real thing, and “pseudo-scientific” imposters.

4. A corresponding preoccupation with identifying the “scientific method,” presumed to explain how the sciences have been so successful.

5. Looking to the sciences for answers to questions beyond their scope.

6. Denying or denigrating the legitimacy or the worth of other kinds of inquiry besides the scientific, or the value of human activities other than inquiry, such as poetry or art.

People who take science to be the only way to gain knowledge, in effect, take science to be a religion, which is ironic since most who push these views are atheists (Richard Dawkins, Sam Harris, Lawrence Kraus). Science is not the only way to gain knowledge; we can also gain knowledge through logic and reasoning. There are analytic truths that are known a priori (Zalta, 1988).

Thus, the claim that there is justification for scientism—that all of our knowledge is derived from the five senses—is false and self-refuting since the belief that scientism is true is a philosophical claim that cannot be empirically tested. There are other ways of knowledge-gaining—of course, without denigrating the knowledge we gain from science—and therefore, scientism is not a justified position. Since there are analytic, a priori truths, then the claim that “rampant empiricism“—scientism—is true, is clearly false.

Note that I am not denying that we can gain knowledge through sense experience; I am denying that it is the only way that we gain knowledge. Even Hossain (2014) concludes that:

Empiricism in the traditional sense cannot meet the demands of enquiries in the fields of epistemology and metaphysics because of its inherent limitations. Empiricism cannot provide us with the certainty of scientific knowledge in the sense that it denies the existence of objective reality, ignores the dialectical relationship of the subjective and objective contents of knowledge.

Quite clearly, it is not rational to be an empiricist—a rampant empiricist that believes that sense experience is the only way to acquire knowledge—since there are other ways of gaining knowledge that are not only based on sense experience. In any case, the argument I’ve formulated below proves that scientism is not justified since we can acquire knowledge through logic and reasoning. It is, for these reasons, that we should be against scientism since the claim that science is the only path to knowledge is itself a philosophical and not scientific claim which therefore falsifies the claim that empiricism is true.

Premise 1: Scientism is justified.

Premise 2: If scientism is justified, then science is the only way we can acquire knowledge.

Premise 3: We can acquire knowledge through logic and reasoning, along with science.

Conclusion: Therefore scientism is unjustified since we can acquire knowledge through logic and reasoning.

(The Lack of) IQ Construct Validity and Neuroreductionism

2400 words

Construct validity for IQ is fleeting. Some people may refer to Haier’s brain imaging data as evidence for construct validity for IQ, even though there are numerous problems with brain imaging and that neuroreductionist explanations for cognition are “probably not” possible (Uttal, 2014; also see Uttal, 2012). Construct validity refers to how well a test measures what it purports to measure—and this is non-existent for IQ (see Richardson and Norgate, 2014). If the tests did test what they purport to (intelligence), then they would be construct valid. I will show an example of a measure that was validated and shown to be reliable without circular reliance of the instrument itself; I will show that the measures people use in attempt to prove that IQ has construct validity fail; and finally I will provide an argument that the claim “IQ tests test intelligence” is false since the tests are not construct valid.

Jung and Haier (2007) formulated the P-FIT hypothesis—the Parieto-Frontal Intelligence Theory. The theory purports to show how individual differences in test scores are linked to variations in brain structure and function. There are, however, a few problems with the theory (as Richardson and Norgate, 2007 point out in the same issue; pg 162-163). IQ and brain region volumes are experience-dependent (eg Shonkoff et al, 2014; Betancourt et al, 2015; Lipina, 2016; Kim et al, 2019). So since they are experience-dependent, then different experiences will form different brains/test scores. Richardson and Norgate (2007) state that such bigger brain areas are not the cause of IQ, rather that, the cause of IQ is the experience-dependency of both: exposure to middle-class knowledge and skills leads to a better knowledge base for test-taking (Richardson, 2002), whereas access to better nutrition would be found in middle- and upper-classes, which, as Richardson and Norgate (2007) note, lower-quality, more energy-dense foods are more likely to be found in lower classes. Thus, Haier et al did not “find” what they purported too, based on simplistic correlations.

Now let me provide the argument about IQ test experience-dependency:

Premise 1: IQ tests are experience-dependent.

Premise 2: IQ tests are experience-dependent because some classes are more exposed to the knowledge and structure of the test by way of being born into a certain social class.

Premise 3: If IQ tests are experience-dependent because some social classes are more exposed to the knowledge and structure of the test along with whatever else comes with the membership of that social class then the tests test distance from the middle class and its knowledge structure.

Conclusion 1: IQ tests test distance from the middle class and its knowledge structure (P1, P2, P3).

Premise 4: If IQ tests test distance from the middle class and its knowledge structure, then how an individual scores on a test is a function of that individual’s cultural/social distance from the middle class.

Conclusion 2: How an individual scores on a test is a function of that individual’s cultural/social distance from the middle class since the items on the test are more likely to be found in the middle class (i.e., they are experience-dependent) and so, one who is of a lower class will necessarily score lower due to not being exposed to the items on the test (C1, P4)

Conclusion 3: IQ tests test distance from the middle class and its knowledge structure, thus, IQ scores are middle-class scores (C1, C2).

Still further regarding neuroimaging, we need to take a look at William Uttal’s work.

Uttal (2014) shows that “The problem is that both of these approaches are deeply flawed for methodological, conceptual, and empirical reasons. One reason is that simple models composed of a few neurons may simulate behavior but actually be based on completely different neuronal interactions. Therefore, the current best answer to the question asked in the title of this contribution [Are neuroreductionist explanations of cognition possible?] is–probably not.”

Uttal even has a book on meta-analyses and brain imaging—which, of course, has implications for Jung and Haier’s P-FIT theory. In his book Reliability in Cognitive Neuroscience: A Meta-meta Analysis, Uttal (2012: 2) writes:

There is a real possibility, therefore, that we are ascribing much too much meaning to what are possibly random, quasi-random, or irrelevant response patterns. That is, given the many factors that can influence a brain image, it may be that cognitive states and braib image activations are, in actuality, only weakly associated. Other cryptic, uncontrolled intervening factors may account for much, if not all, of the observed findings. Furthermore, differences in the localization patterns observed from one experiment to the next nowadays seems to reflect the inescapable fact that most of the brain is involved in virtually any cognitive process.

Uttal (2012: 86) also warns about individual variability throughout the day, writing:

However, based on these findings, McGonigle and his colleagues emphasized the lack of reliability even within this highly constrained single-subject experimental design. They warned that: “If researchers had access to only a single session from a single subject, erroneous conclusions are a possibility, in that responses to this single session may be claimed to be typical responses for this subject” (p. 708).

The point, of course, is that if individual subjects are different from day to day, what chance will we have of answering the “where” question by pooling the results of a number of subjects?

That such neural activations gleaned from neuroimaging studies vary from individual to individual, and even time of day in regard to individual, means that these differences are not accounted for in such group analyses (meta-analyses). “… the pooling process could lead to grossly distorted interpretations that deviate greatly from the actual biological function of an individual brain. If this conclusion is generally confirmed, the goal of using pooled data to produce some kind of mythical average response to predict the location of activation sites on an individual brain would become less and less achievable“‘ (Uttal, 2012: 88).

Clearly, individual differences in brain imaging are not stable and they change day to day, hour to hour. Since this is the case, how does it make sense to pool (meta-analyze) such data and then point to a few brain images as important for X if there is such large variation in individuals day to day? Neuroimaging data is extremely variable, which I hope no one would deny. So when such studies are meta-analyzed, inter- and intrasubject variation is obscured.

The idea of an average or typical “activation region” is probably nonsensical in light of the neurophysiological and neuroanatomical differences among subjects. Researchers must acknowledge that pooling data obscures what may be meaningful differences among people and their brain mechanisms. THowever, there is an even more negative outcome. That is, by reifying some kinds of “average,” we may be abetting and preserving some false ideas concerning the localization of modular cognitive function (Uttal, 2012: 91).

So when we are dealing with the raw neuroimaging data (i.e., the unprocessed locations of activation peaks), the graphical plots provided of the peaks do not lead to convergence onto a small number of brain areas for that cognitive process.

… inconsistencies abound at all levels of data pooling when one uses brain imaging techniques to search for macroscopic regional correlates of cognitive processes. Individual subjects exhibit a high degree of day-to-day variability. Intersubject comparisons between subjects produce an even greater degree of variability.

[…]

The overall pattern of inconsistency and unreliability that is evident in the literature to be reviewed here again suggests that intrinsic variability observed at the subject and experimental level propagates upward into the meta-analysis level and is not relieved by subsequent pooling of additional data or averaging. It does not encourage us to believe that the individual meta-analyses will provide a better answer to the localization of cognitive processes question than does any individual study. Indeed, it now seems plausible that carrying out a meta-analysis actually increases variability of the empirical findings (Uttal, 2012: 132).

So since reliability is low at all levels of neuroimaging analysis, it is very likely that the relations between particular brain regions and specific cognitive processes have not been established and may not even exist. The numerous reports purporting to find such relations report random and quasi-random fluctuations in extremely complex systems.

Construct validity (CV) is “the degree to which a test measures what it claims, or purports, to be measuring.” A “construct” is a theoretical psychological construct. So CV in this instance refers to whether IQ tests test intelligence. We accept that unseen functions measure what they purport to when they’re mechanistically related to differences in two variables. E.g, blood alcohol and consumption level nd the height of the mercury column and blood pressure. These measures are valid because they rely on well-known theoretical constructs. There is no theory for individual intelligence differences (Richardson, 2012). So IQ tests can’t be construct valid.

The accuracy of thermometers was established without circular reliance on the instrument itself. Thermometers measure temperature. IQ tests (supposedly) measure intelligence. There is a difference between these two, though: the reliability of thermometers measuring temperature was established without circular reliance on the thermometer itself (see Chang, 2007).

In regard to IQ tests, it is proposed that the tests are valid since they predict school performance and adult occupation levels, income and wealth. Though, this is circular reasoning and doesn’t establish the claim that IQ tests are valid measures (Richardson, 2017). IQ tests rely on other tests to attempt to prove they are valid. Though, as seen with the valid example of thermometers being validated without circular reliance on the instrument itself, IQ tests are said to be valid by claiming that it predicts test scores and life success. IQ and other similar tests are different versions of the same test, and so, it cannot be said that they are validated on that measure, since they are relating how “well” the test is valid with previous IQ tests, for example, the Stanford-Binet test. This is because “Most other tests have followed the Stanford–Binet in this regard (and, indeed are usually ‘validated’ by their level of agreement with it; Anastasi, 1990)” (Richardson, 2002: 301). How weird… new tests are validated with their agreement with other, non-construct valid tests, which does not, of course, prove the validity of IQ tests.

IQ tests are constructed by excising items that discriminate between better and worse test takers, meaning, of course, that the bell curve is not natural, but forced (see Simon, 1997). Humans make the bell curve, it is not a natural phenomenon re IQ tests, since the first tests produced weird-looking distributions. (Also see Richardson, 2017a, Chapter 2 for more arguments against the bell curve distribution.)

Finally, Richardson and Norgate (2014) write:

In scientific method, generally, we accept external, observable, differences as a valid measure of an unseen function when we can mechanistically relate differences in one to differences in the other (e.g., height of a column of mercury and blood pressure; white cell count and internal infection; erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and internal levels of inflammation; breath alcohol and level of consumption). Such measures are valid because they rely on detailed, and widely accepted, theoretical models of the functions in question. There is no such theory for cognitive ability nor, therefore, of the true nature of individual differences in cognitive functions.

That “There is no such theory for cognitive ability” is even admitted by lead IQ-ist Ian Deary in his 2001 book Intelligence: A Very Short Introduction, in which he writes “There is no such thing as a theory of human intelligence differences—not in the way that grown-up sciences like physics or chemistry have theories” (Richardson, 2012). Thus, due to this, this is yet another barrier against IQ’s attempted validity, since there is no such thing as a theory of human intelligence.

Conclusion

In sum, neuroimaging meta-analyses (like Jung and Haier, 2007; see also Richardson and Norgate, 2007 in the same issue, pg 162-163) do not show what they purport to show for numerous reasons. (1) There are, of course, consequences of malnutrition for brain development and lower classes are more likely to not have their nutritional needs met (Ruxton and Kirk, 1996); (2) low classes are more likely to be exposed to substance abuse (Karriker-Jaffe, 2013), which may well impact brain regions; (3) “Stress arising from the poor sense of control over circumstances, including financial and workplace insecurity, affects children and leaves “an indelible impression on brain structure and function” (Teicher 2002, p. 68; cf. Austin et al. 2005)” (Richardson and Norgate, 2007: 163); and (4) working-class attitudes are related to poor self-efficacy beliefs, which also affect test performance (Richardson, 2002). So, Jung and Haier’s (2007) theory “merely redescribes the class structure and social history of society and its unfortunate consequences” (Richardson and Norgate, 2007: 163).

In regard to neuroimaging, pooling together (meta-analyzing) numerous studies is fraught with conceptual and methodological problems, since a high-degree of individual variability exists. Thus, attempting to find “average” brain differences in individuals fails, and the meta-analytic technique used (eg by Jung and Haier, 2007) fails to find what they want to find: average brain areas where, supposedly, cognition occurs between individuals. Meta-analyzing such disparate studies does not show an “average” where cognitive processes occur, and thusly, cause differences in IQ test-taking. Reductionist neuroimaging studies do not, as is popularly believed, pinpoint where cognitive processes take place in the brain, they have not been established and they may not even exist.

Nueroreductionism does not work; attempting to reduce cognitive processes to different regions of the brain, even using meta-analytic techniques as discussed here, fail. There “probably cannot” be neuroreductionist explanations for cognition (Uttal, 2014), and so, using these studies to attempt to pinpoint where in the brain—supposedly—cognition occurs for such ancillary things such as IQ test-taking fails. (Neuro)Reductionism fails.

Since there is no theory of individual differences in IQ, then they cannot be construct valid. Even if there were a theory of individual differences, IQ tests would still not be construct valid, since it would need to be established that there is a mechanistic relation between IQ tests and variable X. Attempts at validating IQ tests rely on correlations with other tests and older IQ tests—but that’s what is under contention, IQ validity, and so, correlating with older tests does not give the requisite validity to IQ tests to make the claim “IQ tests test intelligence” true. IQ does not even measure ability for complex cognition; real-life tasks are more complex than the most complex items on any IQ test (Richardson and Norgate, 2014b)

Now, having said all that, the argument can be formulated very simply:

Premise 1: If the claim “IQ tests test intelligence” is true, then IQ tests must be construct valid.

Premise 2: IQ tests are not construct valid.

Conclusion: Therefore, the claim “IQ tests test intelligence” is false. (modus tollens, P1, P2)

Vegans/Vegetarians vs. Carnivores and the Neanderthal Diet

2050 words

The vegan/vegetarian-carnivore debate is one that is a false dichotomy. Of course, the middle ground is eating both plants and animals. I, personally, eat more meat (as I eat a high protein diet) than plants, but the plants are good for a palate-switch-up and getting other nutrients in my diet. In any case, on Twitter, I see that there is a debate between “carnivores” and “vegans/vegetarians” on which diet is healthier. I think the “carnivore” diet is healthier, though there is no evolutionary basis for the claims that they espouse. (Because we did evolve from plant-eaters.) In this article, I will discuss the best argument for ethical vegetarianism and the evolutionary basis for meat-eating.

Veganism/Vegetarianism

The ethical vegetarian argument is simple: Humans and non-human animals deserve the same moral consideration. Since they deserve the same moral consideration and we would not house humans for food, it then follows that we should not house non-human animals for food. The best argument for ethical vegetarianism comes from Peter Singer from Unsanctifying Animal Life. Singer’s argument also can be extended to using non-human animals for entertainment, research, and companionship.

Any being that can suffer has an interest in avoiding suffering. So the equal consideration of interests principle (Guidi, 2008) asserts that the ability to suffer applies to both human and non-human animals.

Here is Singer’s argument, from Just the Arguments: 100 of the Most Important Arguments in Western Philosophy (pg. 277-278):

P1. If a being can suffer, then that being’s interests merit moral consideration.

P2. If a being cannot suffer, then that beings interests do not merit moral consideration.

C1. If a being’s interests merit moral consideration, then that being can suffer (transposition, P2).

C2. A being’s interests merit moral consideration if and only if that being can suffer (material equivalence, P1, C1).

P3. The same interests merit the same moral consideration, regardless of what kind of being is the interest-bearer (equal consideration of interests principle).

P4. If one causes a being to suffer without adequate justification, then one violates that being’s interests.

P5. If one violates a being’s interests, then one does what is morally wrong.

C3. If one causes a being to suffer without adequate justification, then one does what is morally wrong (hypothetical syllogism, P4, P5).

P6. If P3, then if one kills, confines, or causes nonhuman animals to experience pain in order to use them as food, then one causes them to suffer without adequate justification.

P7. If one eats meat, then one participates in killin, confining, and causing nonhuman animals to experience pain in order to use them as food.

C4. If one eats mea, then one causes nonhuman animals to suffer without adequate justification (hypothetical syllogism, P6, P7).

C5. If one eats meat, the one does what is morally wrong (hypothetical syllogism, C3, C4).

This argument is pretty strong, indeed it is sound. However, I personally will never eat a vegetarian/vegan diet because I love eating meat too much. (Steak, turkey, chicken.) I will do what is morally wrong because I love the taste of meat.

In an evolutionary context, the animals we evolved from were plant-eaters. The amount of meat in our diets grew as we diverged from our non-human ancestors; we added meat through the ages as our tool-kit became more complex. Since the animals we evolved from were plant-eaters and we added meat as time went on, then, clearly, we were not “one or the other” in regard to diet—our diet constantly changed as we migrated into new biomes.

So although Singer’s argument is sound, I will never become a vegan/vegetarian. Fatty meat tastes too good.

Nathan Cofnas (2018) argues that “we cannot say decisively that vegetarianism or veganism is safe for children.” This is because even if the vitamins and minerals not gotten through the diet are supplemented, the bioavailability of the consumed nutrients are lower (Pressman, Clement, and Hayes, 2017). Furthermore, pregnant women should not eat a vegan/vegetarian diet since vegetarian diets can lead to B12 and iron deficiency along with low birth weight and vegan diets can lead to DHZ, zinc, and iron deficiencies along with a higher risk of pre-eclampsia and inadequate fetal brain development (Danielewicz et al, 2017). (See also Tan, Zhao, and Wang, 2019.)

Carnivory

Meat was important to our evolution, this cannot be denied. However, prominent “carnivores” take this fact and push it further than it goes. Yes, there is data that meat-eating allowed our brains to grow bigger, trading-off with body size. Fonseca-Azevedo and Herculano-Houzel (2012) showed that metabolic limitations resulting from hours of feeding and low caloric yield explain the body/brain size in great apes. Plant foods are low in kcal; great apes have large bodies and so, need to eat a lot of plants. They spend about 10 to 11 hours per day feeding. On the other hand, our brains started increasing in size with the appearance of erectus.

If erectus ate nothing but raw foods, he would have had to eat more than 8 hours per day while hominids with neurons around our level (about 86 billion; Herculano-Houzel, 2009). Thus, due to the extreme difficulty of attaining the amount of kcal needed to power the brains with more neurons, it is very unlikely that erectus would have been able to survive on only plant foods while eating 8+ hours per day. Indeed, with the archaeological evidence we have about erectus, it is patently ridiculous to claim that erectus did eat for that long. Great apes mostly graze all day. Since they graze all day—indeed, they need to as the caloric availability of raw foods is lower than in cooked foods (even cooked plant foods would have a higher bioavailability of nutrients)—then to afford their large bodies they need to basically do nothing but eat all day.

It makes no sense for erectus—and our immediate Homo sapiens ancestors—to eat nothing but raw plant foods for what amounts to more than a work day in the modern world. If this were the case, where would they have found the time to do everything else that we have learned about them in the archaeological record?

There is genetic evidence for human adaptation to a cooked diet (Carmody et al, 2016). Cooking food denatures the protein in it, making it easier to digest. Denaturation is the alteration of the protein shape of whatever is being cooked. Take the same kind of food. That food will have different nutrient bioavailability depending on whether or not it is cooked. This difference, Herculano-Houzel (2016) and Wrangham (2009) argue is what drove the evolution of our genus and our big brains.

Just because meat-eating and cooking was what drove the evolution of our big brains—or even only allowed our brains to grow bigger past a certain point—does not mean that we are “carnivores”; though it does throw a wrench into the idea that we—as in our species Homo sapiens—were strictly plant-eaters. Our ancestors ate a wide-range of foods depending on the biome they migrated to.

The fact that our brain takes up around 20 percent of our TDEE while representing only 2 percent of our overall body mass, the reason being our 86 billion neurons (Herculano-Houzel, 2011). So, clearly, as our brains grew bigger and acquired more neurons, there had to have been a way for our ancestors to acquire the energy need to power their brains and neurons and, as Fonseca-Azevedo and Herculano-Houzel (2012) show, it was not possible on only a plant diet. Eating and cooking meat was the impetus for brain growth and keeping the size of our brains.

Take this thought experiment. An asteroid smashes into the earth. A huge dust cloud blocks out the sun. So the asteroid would have been a cause of lowering food production. This halting of food production—high-quality foods—persisted for hundreds of years. What would happen to our bodies and brains? They would, of course, shrink depending on how much and what we eat. Food scarcity and availability, of course, do influence the brain and body size of primates (Montgomery et al, 2010), and humans would be no different. So, in this scenario I have concocted, in such an event, we would shrink, in both brain and body size. I would imagine in such a scenario that high-quality foods would disappear or become extremely hard to come by. This would further buttress the hypothesis that a shift to higher-quality energy is how and why our large brains evolved.

Neanderthal Diet

A new analysis of the tooth of a Neanderthal apparently establishes that they were mostly carnivorous, living mostly on horse and reindeer meat (Jaouen et al, 2019). Neanderthals did indeed have a high-meat diet in northerly latitudes during the cold season. Neanderthals in Southern Europe—especially during the warmer seasons—however, ate a mixture of plants and animals (Fiorenza et al, 2008). Further, there was a considerable plant component to the diet of Neanderthals (Perez-Perez et al, 2003) (with the existence of plant-rich diets for Neanderthals being seen mostly in the Near East; Henry, Brooks, and Piperno, 2011) while the diet of both Neanderthals and Homo sapiens varied due to climatic fluctuations (El Zataari et al, 2016). From what we know about modern human biochemistry and digestion, we can further make the claim that Neanderthals ate a good amount of plants.

Ulijaszek, Mann, and Elton (2013: 96) write:

‘Absence of evidence’ does not equate to ‘evidence of absence,’ and the meat-eating signals from numerous types of data probably swamp the plant-eating signlas for Neanderthals. Their dietary variability across space and time is consistent with the pattern observed in the hominin clade as a whole, and illustrates hominin dietary adaptatbility. It also mirrors trends observed in modern foragers, whereby those populations that live in less productive environments have a greater (albeit generally not exclusive) dependance on meat. Differences in Neanderthal and modern human diet may have resulted from exploitation of different environments: within Europe and Asia, it has been argued that modern humans exploited marginal areas, such as steppe environments, whereas Neanderthals may have preferred more mosaic, Mediterranean-type habitats.

Quite clearly, one cannot point to any one study to support an (ideologically driven) belief that our genus or Neanderthals were “strictly carnivore”, as there was great variability in the Neanderthal diet, as I have shown.

Conclusion

Singer’s argument for ethical vegetarianism is sound; I personally can find no fault in it (if anyone can, leave a comment and we can discuss it, I will take Singer’s side). Although I can find no fault in the argument, I would never become a vegan/vegetarian as I love meat too much. There is evidence that vegan/vegetarian diets are not good for growing children and pregnant mothers, and although the same can be said for any type of diet that leads to nutrient deficiencies, the risk is much higher in these types of plant-based diets.

The evidence that we were meat-eaters in our evolutionary history is there, but we evolved as eclectic feeders. There was great variability in the Neanderthal diet depending on where they lived, and so the claim that they were “full-on carnivore” is false. The literature attests to great dietary flexibility and variability in both Homo sapiens and Neanderthals, so the claim that they ate meat and only meat is false.

My conclusion in my look into our diet over evolutionary time was:

It is clear that both claims from vegans/vegetarians and carnivores are false: there is no one “human diet” that we “should” be eating. Individual variation in different physiologic processes implies that there is no one “human diet”, no matter what type of food is being pushed as “what we should be” eating. Humans are eclectic feeders; we will eat anything since “Humans show remarkable dietary flexibility and adaptability“. Furthermore, we also “have a relatively unspecialized gut, with a colon that is shorter relative to overall size than in other apes; this is often attributed to the greater reliance on faunivory in humans (Chivers and Langer 1994)” (Ulijaszek, Mann, and Elton, 2013: 58). Our dietary eclectism can be traced back to our Australopithecine ancestors. The claim that we are either “vegetarian/vegan or carnivore” throughout our evolution is false.

There is no evidence for both of these claims from both of these extreme camps; humans are eclectic feeders. We are omnivorous, not vegan/vegetarian or carnivores. Although we did evolve from plant-eating primates and then added meat into our diets over time, there is no evidence for the claim that we ate only meat. Our dietary flexibility attests to that.

Athleticism is Irreducible to Biology: A Systems View of Athleticism

1550 words

Reductionists would claim that athletic success comes down to the molecular level. I disagree. Though, of course, understanding the molecular pathways and how and why certain athletes excel in certain sports can and will increase our understanding of elite athleticism, reductionist accounts do not tell the full story. A reductionist (which I used to be, especially in regard to sports; see my article Racial Differences in Muscle Fiber Typing Cause Differences in Elite Sporting Competition) would claim that, as can be seen in my article, the cause for elite athletic success comes down to the molecular level. Now, that I no longer hold such reductionist views in this area does not mean that I deny that there are certain things that make an elite athlete. However, I was wrong to attempt to reduce a complex bio-system and attempt to pinpoint one variable as “the cause” of elite athletic success.

In the book The Genius of All of Us: New Insights into Genetics, Talent, and IQ, David Shenk dispatches with reductionist accounts of athletic success in the 5th chapter of the book. He writes:

2. GENES DON’T DIRECTLY CAUSE TRAITS; THEY ONLY INFLUENCE THE SYSTEM.

Consistent with other lessons of GxE [Genes x Environment], the surprising finding of the $3 billion Human Genome Project is that only in rare instances do specific gene variants directly cause specific traits or diseases. …

As the search for athletic genes continues, therefore, the overwhelming evidence suggests that researchers will instead locate genes prone to certain types of interactions: gene variant A in combination with gene variant B, provoked into expression by X amount of training + Y altitude + Z will to win + a hundred other life variables (coaching, injuries, etc.), will produce some specific result R. What this means, of course, What this means, of course, is that we need to dispense rhetorically with thick firewall between biology (nature) and training (nurture). The reality of GxE assures that each persons genes interacts with his climate, altitude, culture, meals, language, customs and spirituality—everything—to produce unique lifestyle trajectories. Genes play a critical role, but as dynamic instruments, not a fixed blueprint. A seven- or fourteen- or twenty-eight-year-old is not that way merely because of genetic instruction. (Shenk, 2010: 107) [Also read my article Explaining African Running Success Through a Systems View.]

This is looking at the whole entire system: genes, to training, to altitude, to will to win, to numerous other variables that are conducive to athletic success. You can’t pinpoint one variable in the entire system and say that that is the cause: each variable works together in concert to produce the athletic phenotype. One can invoke Noble’s (2012) argument that there is no privileged level of causation in the production of an athletic phenotype. There are just too many factors that go into the production of an elite athlete, and attempting to reduce it to one or a few factors and attempt to look for those factors in regard to elite athleticism is a fool’s errand. So we can say that there is no privileged level of causation in regard to the athletic phenotype.

In his paper Sport and common-sense racial science, Louis (2004: 41) writes:

The analysis and explanation of racial athleticism is therefore irreducible to

biological or socio-cultural determinants and requires a ‘biocultural approach’

(Malina, 1988; Burfoot, 1999; Entine, 2000) or must account for environmental

factors (Himes, 1988; Samson and Yerl`es, 1988).

Reducing anything, sports included, to environmental/socio-cultural determinants and biology doesn’t make sense; I agree with Louis that we need a ‘biocultural approach’, since biology and socio-cultural determinants are linked. This, of course, upends the nature vs. nurture debate; neither “nature” nor “nurture” has won, they causally depend on one another to produce the elite athletic phenotype.

Louis (2004) further writes:

In support of this biocultural approach, Entine (2001) argues that athleticism is

irreducible to biology because it results from the interaction between population-based genetic differences and culture that, in turn, critiques the Cartesian dualism

‘which sees environment and genes as polar-opposite forces’ (p. 305). This

critique draws on the centrality of complexity, plurality and fluidity to social

description and analysis that is significant within multicultural common sense. By

pointing to the biocultural interactivity of racial formation, Entine suggests that

race is irreducible to a single core determinant. This asserts its fundamental

complexity that must be understood as produced through the process of

articulation across social, cultural and biological categories.

Of course, race is irreducible to a single core determinant; but it is a genuine kind in biology, and so, we must understand the social, cultural, and biological causes and how they interact with each other to produce the athletic phenotype. We can look at athlete A and see that he’s black and then look at his somatotype and ascertain that the reason why athlete A is a good athlete is conducive to his biology. Indeed, it is. One needs a requisite morphology in order to succeed in a certain sport, though it is quite clearly not the only variable needed to produce the athletic phenotype.

One prevalent example here is the Kalenjin (see my article Why Do Jamaicans, Kenyans, and Ethiopians Dominate Running Competitions?). There is no core determinant of Kalenjin running success; even one study I cited in my article shows that Germans had a higher level of a physiological variable conducive to long-distance running success compared to the Kalenjin. This is irrelevant due to the systems view of athleticism. Low Kenyan BMI (the lowest in the world), combined with altitude training (they live in higher altitudes and presumably compete in lower altitudes), a meso-ecto somatotype, the will to train, and even running to and from where they have to go all combine to show how and why this small tribe of Kenyans excel so much in these types of long-distance running competitions.

Sure, we can say that what we know about anatomy and physiology that a certain parameter may be “better” or “worse” in the context of the sport in question, no one denies that. What is denied is the claim that athleticism reduces to biology, and it does not reduce to biology because biology, society, and culture all interact and the interaction itself is irreducible; it does not make sense to attempt to partition biology, society, and culture into percentage points in order to say that one variable has primacy over another. This is because each level of the system interacts with every other level. Genes, anatomy and physiology, the individual, the overarching society, cultural norms, peers, and a whole slew of other factors explain athletic success not only in the Kalenjin but in all athletes.

Broos et al (2016) showed that in those with the RR genotype, coupled with the right morphology and fast twitch muscle fibers, this would lead to more explosive contractions. Broos et al (2016) write:

In conclusion, this study shows that a-actinin-3 deficiency decreases the contraction velocity of isolated type IIa muscle fibers. The decreased cross-sectional area of type IIa and IIx fibers may explain the increased muscle volume in RR genotypes. Thus, our results suggest that, rather than fiber force, combined effects of morphological and contractile properties of individual fast muscle fibers attribute to the enhanced performance observed in RR genotypes during explosive contractions.

This shows the interaction between the genotype, morphology, fast twitch fibers (which blacks have more of; Caeser and Henry, 2015), and, of course, the grueling training these elite athletes go through. All of these factors interact. This further buttresses the argument that I am making that different levels of the system causally interact with each other to produce the athletic phenotype.

Pro-athletes also have “extraordinary skills for rapidly learning complex and neutral dynamic visual scenes” (Faubert, 2013). This is yet another part of the system, along with other physical variables, that an elite athlete needs to have. Indeed, as Lippi, Favalaro, and Guidi (2008) write:

An advantageous physical genotype is not enough to build a top-class athlete, a champion capable of breaking Olympic records, if endurance elite performances (maximal rate of oxygen uptake, economy of movement, lactate/ventilatory threshold and, potentially, oxygen uptake kinetics) (Williams & Folland, 2008) are not supported by a strong mental background.

So now we have: (1) strong mental background; (2) genes; (3) morphology; (4) Vo2 max; (5) altitude; (6) will to win; (7) training; (8) coaching; (9) injuries; (10) peer/familial support; (11) fiber typing; (12) heart strength etc. There are of course myriad other variables that are conducive to athletic success but are irreducible since we need to look at it in the whole context of the system we are observing.

In conclusion, athleticism is irreducible to biology. Since athleticism is irreducible to biology, then to explain athleticism, we need to look at the whole entire system, from the individual all the way to the society that individual is in (and everything in between) to explain how and why athletic phenotypes develop. There is no logical reason to attempt to reduce athleticism to biology since all of these factors interact. Therefore, the systems view of athleticism is the way we should view the development of athletic phenotypes.

(i) Nature and Nurture interact.

(ii) Since nature and nurture interact, it makes no sense to attempt to reduce anything to one or the other.

(iii) Since it makes no sense to attempt to reduce anything to nature or nurture since nature and nurture interact, then we must dispense with the idea that reductionism can causally explain differences in athleticism between individuals.

Race and Menarche

1100 words

Back in 2016 I wrote about racial differences in menarche and how there is good evidence that leptin is a strong candidate for the cause in my article Leptin and its Role in the Sexual Maturity of Black Girls (disregard the just-so stories). Black girls are more likely to hit puberty at a younger age than white girls. Why? One reason may be that leptin may play a role in the accelerated growth and maturation of black girls, since there was a positive relationship between leptin concentration and obesity in black girls (Wagner and Heyward, 2000). When girls start to develop at younger and younger ages, a phrase you hear often is “It’s the chemicals in the food” in regard to, for example, early breast development on a young, pre-teen girl.

Black girls are more likely to be obese than white girls (Freedman et al, 2000) and it is thought that body fat permits the effects of earlier menarche due to leptin being released from the adipocyte (fat cell) (Salsberry, Reagen, and Pajer, 2010). Freedman et al (2000) showed that black girls experienced menarche 3 months earlier than white girls on average, while over a 20 year period the median age decreased by 9.5 months. There is also evidence of earlier thelarche (breast development) in black girls, which was mediated by gonadotropin (Cabrera et al, 2014). Wong et al (1998) found that circulating serum leptin levels were correlated with earlier menarche in black girls which was related to body fatness and age but lessened after fat mass, maturation and physical fitness. There is a ton of evidence that exists that body fatness is related to obesity and, as I said above, the mechanism is probably fat cells releasing leptin, permitting earlier menarche (see Kaplowitz, 2008). Higher levels of body fat cause earlier menarche; earlier menarche does not cause higher levels of body fat. The evidence is there that leptin indeed plays the permissive role to allow a girl to enter into puberty earlier, and that this is how and why black girls enter menarche earlier than white girls.

So when fat mass increases, so does leptin; when leptin increases, girls have puberty at an earlier age (Apter, 2009). Black girls have higher levels of circulating leptin than white girls (Ambrosious et al, 1998). So knowing the relationship between leptin and obesity and how fat cells release leptin into the body permissing earlier puberty, we can confidently say that leptin is a major cause of earlier pubertal development in black girls. Total body fat correlates with fasted leptin (Ebenibo et al, 2018).

Siervogel et al (2003) write: