2350 words

Japan has a caste system just like India. Their lowest caste is called “the Burakumin”, a hereditary caste created in the 17th century—the descendants of tanners and butchers. (Buraku means ‘hamlet people’ in Japanese which took on a new meaning in the Meiji era.) Even though they gained “full rights” in 1871, they were still discriminated against in housing and work (only getting menial jobs). A Burakumin Liberation League has formed, to end discrimination against Buraku in 1922, protesting to end job discrimination by the dominant Ippan Japanese. Official numbers of the number of Buraku in Japan are about 1.2 million, but unofficial numbers bring it up to 6000 communities and 3 million Buraku.

Note the similarities here with black Americans. Black Americans got their freedom from American slavery in 1865. The Burakumin got theirs in 1865. Both groups get discriminated against—the things that the Burakumin face, the blacks in America have faced. De Vos (1973: 374) describes some employment statistics for Buraku and non-Buraku:

For instance, Mahara reports the employment statistics for 166 non-Buraku children and 83 Buraku children who were graduated in March 1859 from a junior high school in Kyoto. Those who were hired by small-scale enterprises employing fewer than ten workers numbered 29.8 percent of the Buraku and 13.1 percent of the non-Buraku children; 15.1 percent of non-Buraku children obtained work in large-scale industries employing more than one thousand workers, whereas only 1.5 percent of Buraku children did so.

Certain Japanese communities—in southwestern Japan—have a belief and tradition in having foxes as pets. Those who have the potential to have such foxes descends down the family line—there are “black” foxes and “white” foxes. So in this area in southwestern Japan, people are classified as either “white” or “black”, and marriage between these artificial color lines is forbidden. They believe that if someone from the “white” family marries someone from the “black” family that every other member of the “white” family becomes “black.”

Discrimination against the Buraku in Japan is so bad, that a 330 page list of Buraku names and community placements were sold to employers. Burakumin are also more likely to join the Yakuza criminal gang—most likely due to such opportunities they miss out on in their native land. (Note similarities between Buraku joining Yakuza and blacks joining their own ethnic gangs.) It was even declared that an “Eta” (the lowest of the Burakumin) was 1/7th of an ordinary person. This is eerily familiar to how blacks were treated in America with the three-fifths compromise—signifying that the population of slaves would be counted as three-fifths in total when being apportioned to votes for the Presidential electors, taxes and other representatives.

Now let’s get to the good stuff: “intelligence.” There is a gap in scores between “blacks”, “whites”, and Buraku. De Vos (1973: 377) describes score differences between “blacks”, “whites” and Buraku:

[Nomura] used two different kinds of “intelligence” tests, the nature of which are unfortunately unclear from his report. On both tests and in all three schools the results were uniform: “White” children averaged significantly higher than children from “black” families, and Buraku children, although not markedly lower than the “blacks,” averaged lowest.

According to Tojo, the results of a Tanaka-Binet Group I.Q. Test administered to 351 fifth- and sixth-grade children, including 77 Buraku children, at a school in Takatsuki City near Osaka shows that the I.Q. scores of the Buraku children are markedly lower than those of the non-Buraku children. [Here is the table from Sternberg and Grigorenko, 2001]

Also see the table from Hockenbury and Hockenbury’s textbook Psychology where they show IQ score differences between non-Buraku and Buraku people:

De Vos (1973: 376) also notes the similarities between Buraku and black and Mexican Americans:

Buraku school children are less successful compared with the majority group children. Their truancy rate is often high, as it is in California among black and Mexican-American minority groups. The situation in Japan also probably parallels the response to education by certain but not all minority groups in the United States.

How similar. There is another group in Japan that is an ethnic minority that is the same race as the Japanese—the Koreans. They came to Japan as forced labor during WWII—about 7.8 million Koreans were conscripted to the Japanese, men participating in the military while women were used as sex slaves. Most are born in Japan and speak no Korean, but they still face discrimination—just like the Buraku. There are no IQ test scores for Koreans in Japan, but there are standardized test scores. Koreans in America are more likely to have higher educational attainment than are native-born Americans (see the Pew data on Korean American educational attainment). But this is not the case in Japan. The following table is from Sternberg and Grigorenko (2001).

Just as Koreans do better than white Americans on standardized tests (and IQ tests), how weird is it for Koreans in Japan to score lower than ethnic Japanese and even the Burakumin? Sternberg and Grigorenko (2001) write:

Based on these cross-cultural comparison, we suggest that it is the manner in which caste and minority status combine rather than either minority position or low-caste status alone that lead to low cognitive or IQ test scores for low-status groups in complex, technological societies such as Japan and the United States. Often jobs and education require the adaptive intellectual skills of the dominant caste. In such societies, IQ tests discriminate against all minorities, but how the minority groups perform on the tests depends on whether they became minorities by immigration or choice (voluntary minorities) or were forced by the dominant group into minorities status (involuntary minorities). The evidence indicates that immigrant minority status and nonimmigrant status have different implications for IQ test performance.

The distinction between “voluntary” and “involuntary” minority is simple: voluntary minorities emigrate by choice, whereas involuntary minorities were forced against their will to be there. Black Americans, Native Hawaiians and Native Americans are involuntary minorities in America and, in the case of blacks, they face similar discrimination to the Buraku and there is a similar difference in test scores between the high and low castes (classes in America). (See the discussion in Ogbu and Simons (1998) on voluntary and involuntary minorities and also see Shimihara, (1984) for information on how the Burakumin are discriminated against.)

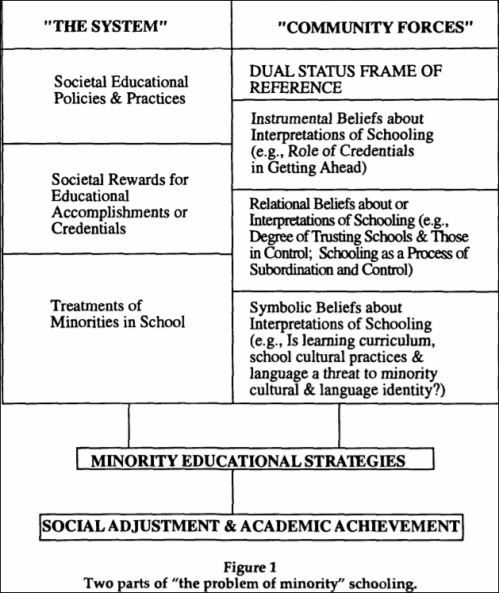

Ogbu and Simons (1988) explain the school performance of minorities using what Ogbu calls a “cultural-ecological theory” which considers societal and school factors along with community dynamics in minority communities. The first part of the theory is that minorities are discriminated against in terms of education, which Ogbu calls “the system.” The second part of the theory is how minorities respond to their treatment in the school system, which Ogbu calls “community forces.” See Figure 1 from Ogbu and Simons (1998: 156):

Ogbu and Simon (1998: 158) write about the Buraku and Koreans:

Consider that some minority groups, like the Buraku outcast in Japan, do poorly in school in their country of origin but do quite well in the United States, or that Koreans do well in school in China and in the United States but do poorly in Japan.

Ogbu (1981: 13) even notes that when Buraku are in America—since they do not look different from the Ippan—they are treated like regular Japanese-Americans who are not discriminated against in America as the Buraku are in Japan and, what do you know, they have similar outcomes to other Japanese:

The contrasting school experiences of the Buraku outcastes in Japan and in the United States are even more instructive. In Japan Buraku children continue massively to perform academically lower than the dominant Ippan children. But in the United States where the Buraku and the Ippan are treated alike by the American people, government and schools, the Buraku do just as well in school as the Ippan (DeVos 1973; Ito,1967; Ogbu, 1978a).

So, clearly, this gap between the Buraku and the Nippon disappears when they are not stratified in a dominant-subordinate relation. It’s because IQ testing and other tests of ability are culture-bound (Cole, 2004) and so, when Burakumin emigrate to America (as voluntary minorities), they are seen as and treated like any other Japanese since there are no physical differences between them and their educational attainment and IQs match the other non-Burakumin Japanese. The very items on these tests are biased towards the dominant (middle-)class—so when the Buraku and Koreans emigrate to America they then have the types of cultural and psychological tools (Richardson, 2002) to do well on the tests and so, their scores change from when they were in their other country.

Note the striking similarities between black Americans and Buraku and Korean-Japanese—all three groups are discriminated against in their countries, all three groups have lower levels of achievement than the majority population, two groups (the Buraku and black Americans, there is no IQ data for Koreans in Japan that I am aware of) show the same gap between them and the dominant group, the Buraku and black Americans got their freedom at around the same times but still face similar types of discrimination. However, when Buraku and Korean-Japanese people emigrate here to America, their IQ scores and educational attainment match that of other East Asian groups. To Americans, there is no difference between Buraku and non-Buraku Japanese people.

Koreans in Japan “endure a climate of hate“, according to The Japan Times. Koreans are heavily discriminated against in Japan. Korean-Japanese people, in any case, score worse than the Buraku. Though, as we all know, when Koreans emigrate to America they have higher test scores than whites do.

Note, though, IQ scores for “voluntary minorities” that came to the US in the 1920s. The Irish, Italians, and even Jews were screened as “low IQ” and were thusly barred entry into the country due to it. For example, Young (1922: 422) writes that:

Over 85 per cent. of the Italian group, more than 80 per cent. of the Polish group and 75 per cent. of the Greeks received their final letter grades from the beta or other performance examination.

While Young (1922) shows the results of an IQ test administered to Southern Europeans in certain areas (one of the studies was carried out in New York City):

These types of score differentials are just like what these lower castes in Japan and America show today. Though, as Thomas Sowell noted in regard to the IQs of Jews, Polish, Italians, and Greeks:

Like fertility rates, IQ scores differ substantially among ethnic groups at a given time, and have changed substantially over time— reshuffling the relative standings of the groups. As of about World War I, Jews scored sufficiently low on mental tests to cause a leading “expert” of that era to claim that the test score results “disprove the popular belief that the Jew is highly intelligent.” At that time, IQ scores for many of the other more recently arrived groups—Italians, Greeks, Poles, Portuguese, and Slovaks—were virtually identical to those found today among blacks, Hispanics, and other disadvantaged groups. However, over the succeeding decades, as most of these immigrant groups became more acculturated and advanced socioeconomically, their IQ scores have risen by substantial amounts. Jewish IQs were already above the national average by the 1920s, and recent studies of Italian and Polish IQs show them to have reached or passed the national average in the post-World War II era. Polish IQs, which averaged eighty-five in the earlier studies—the same as that of blacks today—had risen to 109 by the 1970s. This twenty-four-point increase in two generations is greater than the current black-white difference (fifteen points). [See also here.]

Ron Unz notes that Sowell says about the Eastern and Southern European immigrants IQs: “Slovaks at 85.6, Greeks at 83, Poles at 85, Spaniards at 78, and Italians ranging between 78 and 85 in different studies.” And, of course, their IQs rose throughout the 20th century. Gould (1996: 227) showed that the average mental age for whites was 13.08, with anything between 8 and 12 being denoted a “moron.” Gould noted that the average Russian had a mental age of 11.34, while the Italian was at 11.01 and the Pole was at 10.74. This, of course, changed as these immigrants acclimated to American life.

For an interesting story for the creation of the term “moron”, see Dolmage’s (2018: 43) book Disabled Upon Arrival:

… Goddard’s invention of [the term moron] as a “signifier of tainted whiteness” was the “most important contribution to the concept of feeble-mindedness as a signifier of racial taint,” through the diagnosis of the menace of alien races, but also as a way to divide out the impure elements of the white race.

The Buraku are a cultural class—not a racial or ethnic group. Looking at America, the terms “black” and “white” are socialraces (Hardimon, 2017)—so could the same reasons for low Buraku educational attainment and IQ be the cause for black Americans’ low IQ and educational attainment? Time will tell, though there are no countries—to the best of my knowledge—that blacks have emigrated to and not been seen as an underclass or ‘inferior.’

The thesis by Ogbu is certainly interesting and has some explanatory power. The fact of the matter is that IQ and other tests of ability are bound by culture, and so, when the Buraku leave Japan and come to America, they are seen as regular Japanese (I’m not aware if Americans know about the Buraku/non-Buraku distinction) and they score just as well if not better than Americans and other non-Buraku Japanese. This points to discrimination and other environmental causes as the root of Buraku problems—noting that the Buraku became “full citizens” in 1871, 6 years after black slavery was ended in America. That Koreans in Japan also have similarly low educational attainment but high in America—higher than native-born Americans—is yet another point in favor of Ogbu’s thesis. The “system” and “community forces” seem to change when the two, previously low-scoring, high-crime group comes to America.

The increase in IQ of Southern and Eastern European immigrants, too, is another point in favor of Ogbu. Koreans and Buraku (indistinguishable from other native Japanese), when they leave Japan, are seen as any other Asians immigrants, and so, their outcomes are different.

In any case, the Buraku of Japan and Koreans who are Japanese citizens are an interesting look into how a group is treated can—and does—decrease test scores and social standing in Japan. Might the same hold true for blacks one day?

Interesting post.

A question to its author, RaceRealist:

What is your own personal definition of ‘Race Realism’?

(If you have an article elsewhere that explains this, can I get the link?)

Thx.

LikeLike

.the reason I ask is because your posts don’t follow the convention race realist party line. So I’m left wondering if you really do consider yourself one.

LikeLike

I would like to point out to the author that the three-fifths compromise in the U.S. Constitution was all about adding 60% of people in slavery to the total number of the population of a state, not about counting a black as three-fifths of a person.

LikeLike

..the reason I ask is because your posts don’t follow the convention race realist party line. So I’m left wondering if you really do consider yourself one.

LikeLike

disregard my comment above–it was meant for the other comment not Mark C’s. Please delete.

LikeLike

Here’s a Jason Malloy comment on Burakumin in USA, from:

“I often see media assertions like Steve Olson in The Atlantic: “Yet when the Buraku emigrate to the United States, the IQ gap between them and other Japanese vanishes.” This claim is somewhat apocryphal. There is no data for Burakumin in the US. False claims about US IQ data have mutated second-hand from John Ogbu who claimed a study showed that the Baraku immigrants here “do slightly better in school than the other Japanese immigrants”. The book chapter Ogbu references for this claim (Ito 1966) however, is by a pseudonymous author who relied strictly on gossip from non-outcast Japanese communities in California to surmise how the outcasts here might be performing. The author’s informants believed the US outcasts were more attractive, more fair-skinned, and made more money. Though– as a testament to Ogbu’s immaculate scholarship– the author reported no gossip about how these Burakumin performed in school.

Ito, H. (1966) Japan’s outcastes in the United States. In G.A. deVos and H. Wagatsuma (eds.), Japan’s Invisible Race. Berkeley: University of California Press.

”

“Here’s one from a textbook. It’s pretty appalling stuff… yet typical:

“But when Burakumin families immigrate to the United States, they are treated like any other Japanese. The children do just as well in school–and on IQ tests– as any other Japanese-Americans. (Ogbu 1986)”

So not only does Ogbu make claims that go beyond his source, the scientists and journalists that cite Ogbu follow his lead and make up even more amazing lies about what Ogbu said. It’s all for the greater good!”

LikeLike

There is another thing which came to my mind recently: alcohol consumption and the impact on IQ. I know that Poles today really drink a lot less than POles in the beginning of the century. It would be interesting to compare alcohol consumption of Polish immigrants to USA (especially in the younger cohorts) and compare them to the relevant modern age cohorts. Combined with many similar other factors (parasites; malnourishment, maybe; lead poisoning maybe) they could be responsible for the low IQ reported for Polish immigrants in the early 1900s… though, of course, the another question is whether it’s really valid to compare tests from 1920s to modern tests; the article you quoted is quite vague on the tests used.

LikeLike